Link – History of Neoliberalism

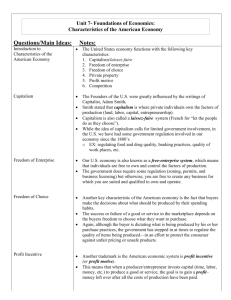

advertisement