Master Plan: draft Energy Chapter v6 in Word

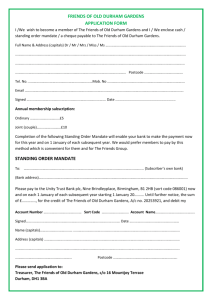

advertisement