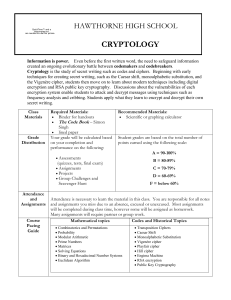

Final Presentation

Implementing and Breaking

Cryptographic Algorithms

CS651 Security

April 18, 2001

Shaun Arnold, Thomas Daniels, Chris Taylor, Mike Walker

Overview

• Cryptography seems like a great idea but …

– how easily is it broken

– how well designed are the algorithms

– what are performance trade offs

– can it be analyzed

• Goal: Find answers or postulations to most

(or all) of these questions

Outline

• Mono-alphabetic ciphers

• Poly-alphabetic ciphers (Vigenere)

• Rotor machine

• Statistical analyzer

• Breaking mono-alphabetic cipher

• Key length analysis

• Breaking poly-alphabetic cipher

• RSA

• Breaking the RSA implementation

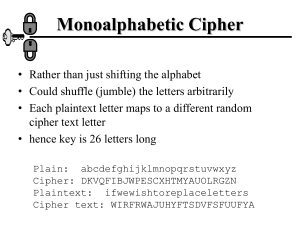

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

• Definition

– A technique that replaces a single letter with another single letter.

An example: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

T H O M A S U V W X Y Z B D C F G I J K E L N Q R P

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

• Caesar Cipher

– Replaces each letter of the alphabet with the letter three places down in the alphabet.

• General Shift Cipher

– Replace each letter of the alphabet with the letter n places down in the alphabet with wrapping.

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

• Keyspace

– Normal: 26! keys

– Shift cipher: 25 keys

• Strengths

– Easy computation.

– Fast to encrypt and decrypt.

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

• Weaknesses

– For the shift cipher, there are only 25 keys.

– Sentence structure is maintained

– Regularities of the language are maintained.

Polyalphabetic Ciphers

• Definition

– The use of multiple monoalphabetic substitutions as one proceeds through a plaintext message.

– Includes:

A set of related monoalphabetic substitution rules

A key determines which rule to choose.

Polyalphabetic Ciphers

• Strengths

– Stronger than monoalphabetic

– Large keyspace

• Example: Vigenere

– Given a key letter x and a plaintext letter y , the ciphertext is at the intersection of the row labeled x and the column labeled and the column labeled y.

Polyalphabetic Ciphers

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

A A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

B B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A

C C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B

D D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C

E E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D

F F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E

G G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F

H H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G

I I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H

J J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I

K K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J

L L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K

M M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L

N N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M

O O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N

P P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O

Q Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P

R R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q

S S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R

T T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S

U U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T

V V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U

W W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V

X X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W

Y Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X

CARS CA RSCARS CARS

THIS IS REALLY COOL

VHZK KS IWCLCQ EOFD

Z Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y

Rotor Machines

• Another form of letter substitution

• Used during World War II by the Germans and the

Japanese (enigma and purple)

• Hardwired connections from 26 incoming contacts to 26 outgoing contacts on each rotor

• As each letter was typed, the rotors would rotate like an odometer

• Key for a message would consist of initial configuration of the rotors (26^3 keyspace)

Software implementation of rotor

• An array of 26 offsets specifies the contact configuration of one rotor

– only one-to-one correspondences are allowed

– 26! possible configurations for each rotor

• (26!)^3 possible different machines could be built

• For a particular machine (contacts fixed), there are 26^3 possible initial configurations for a message (key space)

• Letter substitution repeats after 26^3 letters

Example ciphertext/plaintext pair

This plaintext is to be encrypted with the rotor engine using the configuration given in

Stalling page forty three in figure eight of chapter two

JSHK RHHKMVNVZ SA ND TC YEZEPWHYK AAGD

NNG YSYKK GVOVFL RRKSY RRI IZNBJKJWTIPTO

YPRET IC IEODDCAZ HZBZ YRKKH YIPCN IK

LOWOJX CJXKK DC MZWAGDJ EOX

Cryptanalysis

“The first step in breaking any cipher is to try to find features which correspond to the original plaintext. Whereas codes substitute groups of letters or figures for words, phrases, or even complete concepts, ciphers replace every individual letter of every individual word. They therefore tend to reflect the characteristics of the original language of the original text. This makes them vulnerable to studies of letter frequency

.”

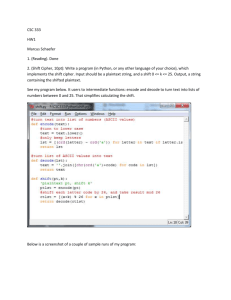

Statistical Frequency Program

• Reports the frequency of occurrence of all individual letters and any double and triple letter groups which appear above a given threshold (e.g. >= 5%)

• Very useful for breaking monoalphabetic ciphers

• Also a good profiler for patterns in specific genres of plaintext

Example of statistical analysis

•

Here is some English prose to get frequency statistics on.

– 1 0 2 0 8 1 2 2 4 0 0 1 1 3 4 1 1 3 7 5 1 0 0 0 1 0

– a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

– 3 2 2 2 2 2 2

– is en et re so st ti

– no three letter groups appeared more than once

• This text is too short to get good results

Breaking the monoalphabetic cipher

• Messages as short as 94 letters were broken relatively easily (~3.6 * key length)

• First run statistical analyzer on ciphertext

• Using resulting statistics and clever observations, begin to make guesses at character substitutions

• Unix tr utility is very useful to progressively substitute into the ciphertext

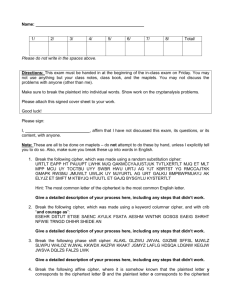

94 letter example

f for se c s rets are e d ge d too e e e l t s an d must a V e e W e N s t from f c rom J hi BP re n a n P f rom G f oo B s G e BB P o n e team s e

G e BB PCO e t R ea m t RXQ s e s r m essa a g e i e Q s a s XCDR

CO e a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x

0 5 10 7 6 0 1 0 10 2 0 0 5 1 5 6 3 7 1 14 0 1 1 3 4 2

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

DT - 3, YDC - 2, EOP - 2, DCM - 2, COT - 2, CCB -2, CBI - 2

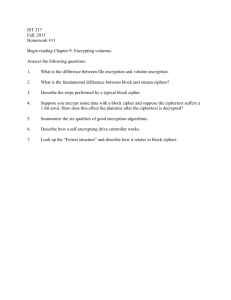

Analyzing the Key Length

• Assume dealing with poly-alphabetic cipher

• Two letter combinations

• Let’s get VERBOSE

• Whoa!, Too Much Information (TMI)

Cracking the Poly

• Establish key length

• Attack (assumed Vigenere)

– Brute-force automation

– Trial and Error (random walk)

– Other clever (or not so clever) means

The Test

• 4 blocks of cipher text of varying length

– 55 char, 10 words

– 4282 char, 765 words

– 4194 char, ? words

– 771 char, 123 words

• Keylengths respectively

– 18?, 7, 11, 7

B & E

• First three had spaces to delimit words

– all but shortest was cracked (and that could have been done with brute force)

– one had unencrypted years (trivial)

– crack time: ~ 2 hours

• No spaces to delimit words

– became much more difficult

– crack time: ~ 5-6 hours

How To Solve It

• Assume “the” is in passage somewhere

• Start at beginning and work it

• Ex.

pgpwhgeIkhbfapwzbsvmjhjzjrrzdgbsyandvirczcnnknptfxikoahjxusioomovmubpr

...

1234567890112345678901123456789011234567890112345678901123456789 nhe nis

DECRYPTED TEXT

POSSIBLE KEY

RSA Encryption

• RSA Implementation

• Attacking RSA Implementation

RSA Implementation

• 64-bit asymmetric block encryption

C = M e mod n

M = C d mod n = (M e mod n) d mod n = M ed mod n

KU = {e, n}; KR = {d, n} n = pq; p and q are large primes

• BigInt class allows arbitrary integer length

– Typical prime: 24-33 decimal digits

– Typical e: 4 digits

– Typical n: 48 – 66 digits

– Latest RSA challenge (n): 155 digits factored in ~5 months (1999)

RSA Game

• Intercept encrypted email message:

Date: Tue, 27 Mar 2001 22:05:41 -0500 (EST)

From: Shaun C. Arnold sca7m@cs.virginia.edu

20105813699066933652114750065334914038566035999047214

40965537435712718982167337205677653313428359179535719

31719124736396128899063853421163843776098975111964558

29319273754942488085059927130420128944948701514530867

5607425258175809522455958025037536184380738224357998

36892698252078898979704532606448317684588947647820846

46138545006120238968599008085448357757447537785680901

6714823353811366414574730869546386941974433807952398 […]

• Assume RSA implementation is known

• Only ciphertext is available

RSA Attack Strategy

• Timing attack: Exploit prime number generator implementation main(){

BigInt P = GetPrime();

BigInt Q = GetPrime();

[…]

GetPrime( ) { srand48( (unsigned int) time(0) );

BigInt N = rand_int( 10 24 , 10 33 ); if( n % 2 == 0) { n = n + 1; } while(!is_prime( N )) { N += 2; } return N;

}

• Total time since project assigned: 7,862,400 seconds

RSA Attack

• Determine search space

– Script measured prime number generation

• 14 - 82 seconds per number on dept. machines

– 12-110 seconds for prime number generation

– Run within ~5 minutes of email timestamp (300 sec.)

– ~30,000 search combinations * 2 min = ~42 days, or

3,628,800 seconds

• Parallel execution of crack program

– 103 450-Mhz PII Linux machines (Centurion)

– ~12 hours running time

RSA Attack Foiled?

Date: Fri, 6 Apr 2001 20:13:52 -0400

From: Andrew Grimshaw <grimshaw@virginia.edu>

To: Michael Pittman Walker <mpw7t@cs.virginia.edu>

Subject: crackdriver

Mike,

This code is killing the net. What is it? It is all over the testnet machines.

Nuke it now please.

Andrew

RSA Attack: Results

• 19 Megs output:

Start: 985748522 Second: 985748581

>c`bW+^E^R#(SbM^]1Z^E^Bi=@=!;^LV\BQRY^G^P^PN0Uz^CY<}b^Vc)@R`

+LT#^P,]^c>{^^YH+*^M85-^W#&[$K*^BS^E

Start: 985748522 Second: 985748582

Anyone who attempts to generate random numbers by deterministic means is of course living in a state of sin

John von Neumann

Start: 985748522 Second: 985748583

,*!F^E&/^F.>Y.^EUM^X^DAaO^C^AXT^[L/0>^PaSGy@^X^S5^PM5B^Rna^B

^X?^V{DE^\C^T^QA WS^O7a'^Y0*

Summary

• Length of text and redundancy influence cryptanalysis

• Long keys make cryptanalysis difficult for poly (keylength:text length)

• RSA (and other algorithms) strength depends on correctness of implementation

Questions?

1. How hard is cryptanalysis without knowing the algorithm?

2. When does cryptanalysis become infeasible?

How hard is cryptanalysis without knowing the algorithm?

• In general, cryptographic strength should not rest on this. Assume the cracker knows.

• Nature of plaintext (CC #, English prose)

– how much of the plaintext space is meaningful?

– Redundancy in message

• Ratio of message length to key length

• Plaintext/Ciphertext pairs

When does cryptanalysis become infeasible?

• Key length >= Message length?

– Focus on the key instead of the message

• One time pad

Example (=rand(lines, columns))

• The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog

– 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 4 1 1 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 1

– a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

– 35 letters total

– only 2 repeated double letter combos (th, he)

– only 1 repeated triple letter combo (the)

Even Better

• The quick brown fox jumps over a lazy dog

– 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 4 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1

– a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

– 33 letters total

– no repeated double letter combos

– no repeated triple letter combos

• Even a monoalphabetic cipher (26 letter key) would be difficult to break