Shakespeare and the English Language

advertisement

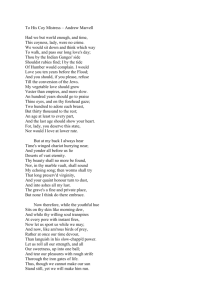

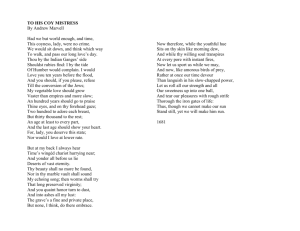

Shakespeare and the English Language Pat Pingeton Martin Baker Spelling • Still varied during Shakespeare’s time • Very few words didn’t exist in the past as they do now, however there were many variations that have since fallen out of use • Some ME conventions still used, especially early on in Shakespeare’s career • Final -e often used arbitrarily, I.E bone vs. OE ban • Modern practice of using u for vowel and v for consonant came into use during first half of seventieth century Spelling Continued • I used to represent both vowel I and consonant J, modern distinction developed sometime after 1639 • I and Y are interchangeable • E is dropped many times and replaced with an apostrophe I.E despriz’d instead of disprized • Doubled consonants used in order to indicate preceding vowel was short, I.E coppy, pollicy • French loan words ending in -ic often add a k to show that consonant was pronounced [k] and not [s], I.E magick, rusticke • Spelling vv occasionally used for w Punctuation • Modern punctuation logical and uniform, Shakespearean rhetorical and varied • Fewer stops, commas then now • If my Uncle thy banished father had banished thy Uncle the Duke my father (As You Like It I.II.9) • Commas used to indicate emphasis • I have heard that Julius Caesar, grew fat with feasting there (Anthony and Cleopatra II.VI.64) • Question mark used as an exclamation mark Punctuation continued • Commas used instead of colon or semicolon to indicate long pause • A calender, a calender, looke in the Almanack, finde out Moone-shine, finde out Moone-shine (Midsummer Night’s Dream III.I.54) • Semicolons used to emphasize preceding word • Thus, what with the war; what with the sweat, what with the fallowes, and what with poverty, I am Custom-shrunke (Measure for Measure I.II.84 • Capitals are used not only for proper names but also for words that have a special significance • Italics used for proper names and quotes, not emphasis Shakespeare’s Foul Papers • Messy handwritten versions of Shakespeare’s plays. • These papers went to a scribe and were then made into a ‘print copy’ • Mistakes and miswrites were made during the conversion process. • What we have now in folio are usually versions of the ‘print copy’. The Foul Papers were often difficult to decipher Hamlet says, “I know a hawk from a handsaw.” There is an ongoing debate whither the actual text said this or “I know a hawk from a heronshaw.” Which are both birds. To be, or not to be QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. To be, or not to be, that is the question, Whether tis nobler in the minde to suffer The slings and arrowes of outragious fortune, Or to take Armes against a sea of troubles, And by opposing, end them, to die to sleepe No more, and by a sleepe, to say we end The hart-ake, and the thousand naturall shocks That flesh is heire to; tis a consummation Deuoutly to be wisht to die to sleepe, To sleepe, perchance to dreame, I there’s the rub, For in that sleepe of death what dreames may come When we haue shuffled off this mortall coyle Must giue vs pause, there’s the respect That makes calamitie of so long life: For who would beare the whips and scornes of time, Th’ opressors wrong, the proude mans contumely, The pangs of despriz’d loue, the lawes delay, To be, or not to be; that is the question: Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And, by opposing, end them. To die, to sleepNo more, and by a sleep to say we end The heartache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to –‘tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream. Ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil Must give us pause. There’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life, For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’opressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of disprized love, the law’s delay The insolence of office, and the spurnes That patient merit of th’vnworthy takes, When he himselfe might his quietas make With a bare bodkin; who would these fardels beare, To grunt and sweat vnder a wearie life, But that the dread of something after death The vndiscouer’d country, from whose borne No trauiler returnes, puzzles the will, And makes vs rather beare those ills we haue, Then flie to others that we know not of. Thus conscience dooes make cowards of vs all, And thus the natiue hiew of resolution Is sicklied ore with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment, With this regard theyr currents turne awry, And loose the name of action. Soft you now, The faire Ophelia, Nimph in thy orizons Be all my sinnes remembred. The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would these fardels bear, To grunt an sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country from whose bourn No traveler returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action. Soft you, now, The fair Ophelia! – Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remembered. Taming of the Shrew QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Wordz thaht r spell’d difruntlie • Thretaning, eies, Gouernour, beautie, doe, whirlewinds, faire, meete, mou’d, fountaine, thicke, berest, budds, thirftie, daigne, soueraigne, painfull, Whil’st, ly’st, warme, lookes, froward, peeuish, sowre, foule, Rebell, gracelesse, asham’d, warre, supremacie, obay, weake, toyle, harts, minde, bigge, haplie, bandie, frowne, Launces, strawes, weaknesse, stomakes, boote, foote, dutie, readie, Fie, Fie, vnknit that threatening vnkinde brow, And dart not scornefull glances from those eies, To wound thy Lord, thy King, thy Gouernour. It blots thy beautie, as frosts doe bite the Meads, Confounds thy fame, as whirlewinds shake faire budds, And in no sence is meete or amiable. A woman mou’d, is like a fountaine troubled, Muddie, ill seeming, thicke, bereft of beautie, And while it is so, none so dry or thirstie Will daigne to sip, or touch one drop of it. Thy husband is thy Lord, thy life, thy keeper, Thy head, thy soueraigne: One that cares for thee, And for thy maintenance, commits his body To painfull labour, both by sea and land: To watch the night in stormes, the day in cold, Whil’st thou ly’st warme at home, secure and safe, Fie, fie, unknit that threat’ning, unkind brow, And dart not scornful glances from those eyes To wound thy lord, thy king, thy governor. It blots thy beauty as frosts do bite the meads, Confounds thy fame as whirlwinds shake fair buds, And in no sense is meet or amiable. A woman moved is like a fountain troubled, Muddy, ill-seeming, thick, bereft of beauty, And while it is so, none so dry or thirsty Will deign to sip or touch one drop of it. Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper, Thy head, thy sovereign, one that cares for thee, And for thy maintenance commits his body To painful labour both by sea and land, To watch the night in storms, the day in colds, Whilst thou liest warm at home, secure and safe, And craues no other tribute at thy hands, But loue, faire lookes, and true obedience; Too little payment for so great a debt. Such dutie as the subiect owes the Prince, Euen such a woman oweth to her husband: And when she is froward, peeuish, sullen, sowre, And not obedient to his honest will, What is she but a foule contending Rebell, And gracelesse Traitor to her louing Lord? I am asham’d that women are so simple, To offer warre, where they should kneele for peace: Or seeke for rule, supremacie, and sway, When they are bound to serue, loue, and obay. Why are our bodies soft, and weake, and smooth, Vnapt to toyle and trouble in the world, But that our soft conditions, and our harts, Should well agree with our externall parts? Come, come, you froward and vnable wormes, My minde hath bin as bigge as one of yours, My heart as great, my reason haplie more, And craves no other tribute at thy hands But love, fair looks, and true obedience, Too little payment for so great a debt. Such duty as the subject owes the prince, Even such a woman oweth to her husband, And when she is froward, peevish, sullen, sour, And not obedient to his honest will, What is she but a foul contending rebel, And graceless traitor to her loving lord? I am ashamed that women are so simple To offer war where they should kneel for peace, Or seek for rule, supremacy, and sway When they are bound to serve, love and obey. Why are our bodies soft, and weak, and smooth, Unapt to toil and trouble in the world, But that our soft conditions and our hearts Should well agree with our external parts? Come, come, you froward and unable worms, My mind hath been as big as one of yours, My heart as great, my reason haply more, To bandie word for word, and frowne for frowne; But now I see our Launces are but strawes: Our strength as weake, our weakenesse past compare, That seeming to be most, which we indeed least are. Then vale your stomackes, for it is no boote, And place your hands below your husbands foote: In token of which dutie, if he please, My hand is readie, may it do him ease. To bandy word for word and frown for frown; But now I see our lances are but straws, Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare, That seeming to be most which we indeed least are. Then vail your stomachs, for it is no boot, And place your hands below your husband’s foot, In token of which duty, if he please, My hand is ready, may it do him ease. Vocabulary in Taming of the Shrew • Many of the words Shakespeare used have since fallen out of use • Daigne- To think worthy of oneself • Adapted word ‘daign’ • Last used in 1879 • Froward – Disposed to go counter to what is demanded or what is reasonable. • Fell out of use in late 19th Century • Peevish- Irritable, querulous, and childishly fretful • Still in use • Bandie – Bandy – To contend strive fight. • Bandie – The Stickleback- Small spiny fish Vocabulary • Mixture of old and new words • Shakespearean characters sometimes coin new words, someone use familiar words in unfamiliar senses • Uses some poetic expressions that don’t make sense to a modern reader • “More and less” meaning people of all ranks used in Macbeth V.IV.9 • Comparison “white as a whalebone” Some Shakespearian Idioms • In my mind’s eye • A foregone conclusion • The very pink of courtesy • “weird” as an adjective “Shakespeare can not be closely associated with any of the plans for enriching the language put fourth by the Elizabethan rhetoricians, such as the use of inkhorn terms, archaisms, and dialect words, though it is possible to find examples in each category.” Introducing new words • Elizabethan spelling has some rules, but was highly variable. • Shakespeare’s introduction of new words happened through the medium of theater (not print), so in a way he added fuel to the fire introducing sometimes difficult words (Provulgate) into the slowly stabilizing system of spelling. So what is the difference? • Many of the differences that appear stark on paper might not have been as easy to pick up on orally • Main differences that could be picked up by listening seem to be in punctuation and flow • Some words and expressions that an Elizabethan would have no trouble picking up on appear strange to modern readers Sources • For the original spelling and form of Shakespeare’s plays, check out William Shakespeare: The Complete Works on course reserve • For information of Shakespeare’s language, check out Andre , Deutsch. The Language of Shakespeare. London: G.L Brook, 1976.