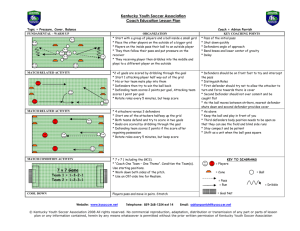

Coaching Manual

advertisement