AERIFinalReport - DSpace at The University of Texas at Austin

advertisement

From the Server to the Virtual Machine: Archiving the AERI 2013 Website for

Preservation in a Trusted Digital Repository

Nicole Feldman

Lauren Gaylord

Amye McCarther

Jim Rizkalla

INF392K: Digital Archiving and Preservation

2

Dr. Patricia Galloway

April 30, 2014

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................... 4

OUR TASK ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4

OUR ROLES ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4

PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................................. 4

ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY .............................................................................................................................................. 5

SCOPE AND CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................... 5

PROJECT GOAL & COLLECTION ASSESSMENT ..................................................................................................... 6

SECTION I: PRESERVATION METHODS .................................................................................................................... 7

AERI 2013 CONFERENCE WEBSITE ................................................................................................................................ 7

WEBSITE OUTLINKS AND WIDGETS ................................................................................................................................ 8

Twitter ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9

Google Maps .......................................................................................................................................................... 10

Outlinks .................................................................................................................................................................... 10

Flickr ........................................................................................................................................................................... 11

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 11

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 11

Sarah Buchanan ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

Lorrie Dong ............................................................................................................................................................. 12

Patricia Galloway ................................................................................................................................................... 13

Jane Gruning........................................................................................................................................................... 13

Sarah Kim................................................................................................................................................................. 13

Virginia Luehrsen .................................................................................................................................................. 13

Katie Pierce Meyer ................................................................................................................................................ 14

SECTION II: DEVELOPMENT OF ARRANGEMENT ............................................................................................... 14

SECTION III: INGEST OF MATERIALS AND METADATA .................................................................................... 15

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION................................................................................................................................... 18

3

LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 18

CONCLUSIONS FOR FUTURE WEB ARCHIVING PROJECTS .......................................................................................... 19

APPENDICES .................................................................................................................................................................... 21

APPENDIX 1: INVENTORY OF WEBSITE FILE DIRECTORY ............................................................................................... 21

APPENDIX 2: JQUERY SCRIPT TO OUTPUT #AERI2013 TWEETS ............................................................................ 23

APPENDIX 3: ARCHIVE READY REPORT ....................................................................................................................... 24

APPENDIX 4: BASECAMP DOCUMENTATION .............................................................................................................. 25

4

INTRODUCTION

Our Task

This project was tasked with archiving the AERI 2013 Conference Website, as well as

the happenings of the conference event, itself.

The 2013 conference was hosted at the University of Texas at Austin and ran from

June 17-21, 2013. Its website, logo, and program were designed by faculty and doctoral

students at UT’s School of Information. Planning for the conference began in the fall of

2012 and the initial website was established November 28, 2012, as was the website’s email

address.

The four project members responsible for archiving the website were students in Dr.

Patricia Galloway’s INF392K: Digital Archiving and Preservation course. These students

were charged with both archiving the website as it existed on the School of Information’s

server and with capturing attendant documentation generated during the creation of the

website and over the course of the conference.

Our Roles

Lauren Gaylord acted as our community administrator and was chiefly responsible

with managing the workflow of our project and ensuring materials were properly ingested

into the repository. Amye McCarther served as the group’s metadata specialist and

managed this aspect of our project workflow and created all the documentation needed

for a successful batch ingest. Nicole Feldman researched and gathered the widget

materials and ran the script to collect conference tweets. She took the lead on

documenting the group’s process. Jim Rizkalla was initially in charge of collecting emails,

but as the scope of our project changed he established contact with many of the creators

and technical staff and set meetings to gather information and documents.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

The project’s primary focus was to capture any information relating to the AERI

2013 website. The first step taken was an initial inventory of the various components

comprising the website, including any widgets and outgoing links. Once a general sense

was gained of the website’s contents and functionality, students and faculty members

identified as contributors to the website and the conference were contacted.

5

Administrative History

AERI (Archival Education and Research Institutes) is a series of annual week-long

conferences funded by a four-year grant from Institute of Museum and Library Sciences

(IMLS) that began in 2009 with the intention of strengthening education and research and

supporting academic cohort-building and mentoring. Goals of AERI include the fostering

of curriculum development and collaborative work.

A key part of AERI’s mission is the encouragement of diversity amongst doctoral

candidates as supported by minority scholarships for undergraduate and graduate

students interested in pursuing doctoral studies in Archival Studies, fellowships for current

doctoral students, and mentorship opportunities.

AERI 2013 was held at the University of Texas at Austin from June 17-21, 2013. The

AERI 2013 website and logo were designed by doctoral candidates at UT’s School of

Information, and supporting materials were supplied by faculty and other students.

Previous institutes were held at UCLA, the University of Michigan, and Simmons College.

The next incarnation of the AERI Institute is scheduled to be hosted at the University of

Pittsburgh in July of 2014. The 2015 Conference will be hosted at the University of

Maryland, College Park.

The accompanying AERI 2013 website was initially designed and implemented by

PhD student Virginia Luehrsen. It was established on November 28, 2012 at

http://www.ischool.utexas.edu/aeri2013/ and contained application forms, scholarship

forms, and Travel and Accommodations information. Edits were made to the website in

December 2012. After registration for AERI 2013 concluded on April 15, 2013, the planning

team posted participants’ bios, the preliminary schedule, an Explore Austin page, and an

Information for Presenters page to the website.

Scope and Contents

The AERI 2013 Website community documents the website maintained by the

University of Texas at Austin School of Information for the 2013 Archival Education and

Research Institute (AERI). The community contains HTML code, PDFs, JPGs, GIFs, PNGs,

mp4 files, docx and doc files, css files, kml files, text files, tar files, and a virtual machine

disk file. The materials in this community were collected and created by Nicole Feldman,

Lauren Gaylord, Amye McCarther, and Jim Rizkalla as part of a class project for Digital

Archiving and Preservation (INF 392K) taught by Dr. Patricia Galloway in Spring 2014.

The website subcommunity contains the underlying directory structure and

encoded representation of the AERI 2013 website. This subcommunity includes a rendering

6

of the pages of the AERI 2013 website in DSpace’s HTML support, screencaptures of the

AERI 2013 website, a virtualization of the AERI website in VirtualBox, and a zipped .tar file

that captures the directory structure of the site as it lives on its hosting server through the

linux rsync function.

The supporting documentation subcommunity contains materials created by

members of the AERI 2013 planning team in the course of conference and website

development. Materials include 7-zip files preserving directory structure as well as JPG and

GIF logo files. Within the 7-zip creator files are MSWord documents, MSExcel

spreadsheets, PowerPoint presentations, MSAccess databases, PDFs, PNGs, JPGs, GIFs, TIFs,

HTML files, CSS files, and TXT files, as well as materials generated by Adobe Photoshop,

Illustrator, and Dreamweaver programs, including EPS, PSD, AI, and MNO files.

The website project documentation subcommunity contains the materials

generated by the INF 392K team regarding the archiving of the website. Files include a

sample spreadsheet used for batch ingest, final report, a data management plan, the SIP

Agreement, and a group presentation.

PROJECT GOAL & COLLECTION ASSESSMENT

Heretofore, web archiving has traditionally been conducted through using web

crawler technologies. However, the code underlying the AERI 2013 Website lives entirely on

an iSchool server, which presented us with the opportunity to capture the look, feel, and

underlying technical architecture of the AERI 2013 Website entirely from the backend. The

website was coded exclusively in HTML and CSS and capturing the directory structure did

not require tremendous programming knowledge. We ultimately chose to use the rsync

linux command in order to create a preservation quality .tar file of the website, to display

the look and feel of the website through HTML support available on DSpace, and to create

a virtualization of the website in Virtual Box in order to greater extend access to the site.

The AERI 2013 Website also contains several outlinks and widgets not hosted by a

local server, and this added a level of complexity to our project. Our group chose to

exclude the outlinks on the page, (excepting the professional websites of Conference

participants) feeling that these items were largely ancillary to the website and the

conference event. Widgets seemed more crucial to providing a portrait of the website and

the conference event, and we decided to document the Google Maps, tweets, and Flickr

7

page established for the event in a manner that would outlive the inevitably temporal

lifespan of these proprietary web applications.

Lastly, the website was designed and the conference was planned by faculty

members and doctoral students at UT’s iSchool, many of whom are still based in Austin

and retained their personal planning documents. Since this supporting documentation was

both so readily available to be securely captured by members of our group and serves to

provide users with a richer sense of the website and the event, our group decided it would

be instructive to include these materials, as well. Items with confidentiality issues like

personal emails or registration lists, as well as very early draft stages of planning materials,

were deemed beyond the scope of our collecting focus. In the end, our group chose to set

up separate collections by creator within a supporting documents subcommunity and to

ingest these supplementary AERI website materials in the order in which they were

received.

SECTION I: PRESERVATION METHODS

AERI 2013 Conference Website

Using the Linux rsync command and capturing the entire file directory of the AERI

2013 Conference Website enabled our group to archive and display the website in a variety

of ways. We created a .tar file to preserve both the directory structure and all of the

public_html files of the AERI Website in a single zipped file. Our first attempt to create the

.tar failed due to a lack of server space allotted to Lauren Gaylord’s iSchool account. After

being temporarily granted more server space by the iSchool webmaster, we successfully

created a .tar file and ingested it into DSpace.

We also installed the open source windows utility, 7Zip, onto our workstation and

were able to extract all of the component files from the .tar. We saved these files to a

folder on the desktop of our workstation. DSpace has built-in HTML support, which allows

websites to be hosted and encoded within the trusted digital repository via an internal

server. We ingested the AERI Website 2013 index.html as our primary bitstream, and then

manually ingested all of these component files and pages as subsequent bitstreams linked

to that main page. Visitors to DSpace only see the single “index.html” file but are able to

experience the AERI 2013 Conference Website in full.

VirtualBox is an open source virtualization software tool developed by Oracle.

Virtualization software is a desktop application that allows users to emulate a software

8

environment of creation by installing a guest operating system on top of a host machine.

While Windows 7 is currently an operating system du jour, “agile development” seems to

be the rallying cry of the entire technology industry, and it could very well fade into

obsolescence in the near future. Our group decided it would be worthwhile to include

virtualization in our preservation strategy and installed a 32 bit Windows 7 Virtual Machine

on our work station.

As other groups had mistakenly downloaded malware while building their virtual

machines, we installed anti-virus software before proceeding with downloads or file

transfers. Though we were originally planning to use Clam AntiVirus software, which is

open-source, we found that the only free, available version for a Windows Operating

System was Immunet 3.0, powered by ClamAV. The free version of Immunet 3.0 only offers

Cloud-based protection, which is not helpful for virus protection in a Virtual Machine. Thus,

we downloaded Windows Endpoint Protection, which was available to us through UT

Austin’s BevoWare website. We also downloaded Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox web

browsers since these browsers were the ones most commonly used to access and view the

site during its creation. Internet Explorer 6 was already installed on the machine.

Once the virtual machine was set up, we used the secure shell client to create an

identical .tar file within the virtual environment, and similarly, installed 7Zip in this

application and were able to extract all component files from the tar. After this step of the

project had been completed, we opened the local file of the AERI 2013 Conference

Website in Chrome and Firefox. In order to prepare the Virtual Machine for ingest, we

uninstalled the secure shell client and 7Zip, which would be of no use to users, and left the

AERI Website open in the two web browsers. Once we were content with the saved

machine state we had established on our virtual box, we manually ingested the Virtual

Machine Disk (VMDK) file into DSpace and provided users with enough descriptive context

to explore the site in the virtual environment.

Website Outlinks and Widgets

Widgets, while especially attractive to website users for their interactivity and

dynamic content, present extraordinary difficulties for preservation. They often utilize

proprietary or commercial formats and draw from externally-hosted content. Unlike other

outlinks such as hyperlinks to repositories and transportation services, widgets involve

embedded content and in this case were more directly relevant to the conference and look

and feel of the website than other outlinks. Therefore, we decided to focus on preserving

the widgets over other, less relevant outlinks.

9

Twitter

An account with the handle @aeri2013 was created and maintained throughout the

planning stages and the 2013 conference event. However, this account was passed on to

the group at University of Pittsburgh who is hosting the 2014 AERI Conference. Twitter

provides users the opportunity to request and download their entire archive in zipped text

file. However, since the AERI Website Creators were no longer in control of this account,

this was not a possibility for our project. Additionally, the account was little used and

mostly for the purpose of announcing registration as well as a call for papers.

Conference participants were encouraged to generate tweets with the hashtag

#AERI2013 over the course of the event, and a widget containing all the tweets tagged this

way is embedded directly on the AERI Website homepage. These tweets provide a

wonderful granular perspective into the conference event and our group thought it would

be highly valuable to capture this facet of the website. As the 2013 Library of Congress

Report on the federal institution’s ongoing Twitter project adeptly remarks, “Archiving and

preserving outlets such as Twitter will enable future researchers access to a fuller picture of

today’s cultural norms, dialogue, trends and events to inform scholarship, the legislative

process, new works of authorship, education and other purposes,” (Twitter Report, 1). Our

group was eager to ensure that this aspect of the AERI Website was accessible to a future

audience.

Ultimately, we chose to capture these tweets in two ways. First, we took screenshots

of the widget as it appears on the AERI homepage, in addition to taking screenshots of all

of the tweets tagged with #AERI2013, which are still live on Twitter’s web application.

Based on the vast amount of data a highly trafficked site like Twitter processes daily, it is

highly unlikely that these tweets will be easily web searchable for much longer and we

wanted to capture these items in a more persistent fashion. In order to accomplish this, we

experimented with writing code that would output all the #AERI2013 in a static HTML page

that would preserve the informational and contextual value of these tweets. Initially we

tried writing a Ruby script for these tweets that would grab from Twitter’s Public API, or

Application Programming Interface, which large websites like Twitter often make freely

available in order to encourage application development. However, Twitter only includes

the preceding six months of tweets in their Public API, and accordingly, the #AERI2013 had

been long deprecated. Instead, we had to grab tweets directly from the Twitter website,

which took some more maneuvering. After some trial and error, we were able to develop a

JQuery script (see Appendix 2) which captured the #AERI2013 tweets in a chronologically

ordered list. This page provided working outlinks to websites embedded in tweets, user

10

pages explicitly mentioned in tweets, and other hashtags users included in tweets. This

second archiving approach offers a considerably more dynamic insight into this aspect of

the conference event and we included this HTML page in this same subcommunity.

Google Maps

As with the Twitter widget, the Google Maps widgets found on the “Travel

Accommodations” webpage presented difficulties as the content is hosted on an external

site and utilizes a unique, proprietary display format. While capturing the look and feel is

ideal, for the map widgets we settled for preserving the look on the webpage through

screenshots and the KML file download option provided by Google.

KML stands for Keynote Markup Language and is an xml notation used to

communicate and visualize geographic data. Though mostly employed by Google

applications including Google Earth and Google Maps, KML is an international standard

maintained by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC). The OGC offers the official schema

for download on its website. Because it is a file format maintained by OGC and an xml

language, we felt confident preserving the files in that format. The file contains information

about location (with geographic coordinates), icons, and names of places (e.g. Wendy's

Restaurant). Thus we anticipate that if the file is opened in ten or fifteen years, it will

display the location and place name that was plotted by the AERI 2013 coordinators for the

conference and will not update to new locations or place names.

Outlinks

The website contains outlinks to other web sites regarding transportation, housing,

local sites to visit and participant web pages. After discussing to what degree our group

should pursue capturing content hosted on other web pages, we decided that commercial

websites were outside the scope of our collection. Likewise, institutional websites were

deemed out of scope due to their size and complexity as well as the potential of

encountering rights issues regarding their contents. However, given that participant web

sites are a direct reflection of the archiving community’s members and their research

interests, in combination with the likelihood that they will not remain stable over the long

term, we decided that it would be appropriate to archive the homepages of participants’

websites linked to from the AERI 2013 “Participants’ Bios” page. Screenshots of these pages

were taken by Amye McCarther at various locations scrolling down the pages and

11

reassembled as composite images in Photoshop. These composite images were exported

as TIFs and ingested on April 26, 2014.

Flickr

After the conclusion of the AERI 2013 conference, a Flickr group was created on

June 26, 2013 and a link to the group was placed on the AERI 2013 website. Digital

photographs of the event were uploaded to Flickr by Lorrie Dong. Because Flickr is an

active website and its interface and design are likely to change in the coming years, we

decided to take a screenshot of its presentation to capture its look while the AERI 2013

website was actively used. This screenshot was taken by Lauren Gaylord on April 23, 2014

and ingested on April 26, 2014. Additionally we decided to download the photographs in

the group for ingest into DSpace so that they would be accessible even if Flickr changes its

format or ceases to exist. The group consisted of 85 photographs, though Flickr mistakenly

listed the count as 96. These JPG files were downloaded at their original size by Lauren

Gaylord on April 23, 2014 and were ingested on April 26, 2014.

Supporting Documents

Introduction

Many of the doctoral students involved in both the creation of the AERI 2013

Website and the planning of the AERI 2013 Conference Event are still based in Austin.

These students were very responsive to our inquiries when were conducting research

about AERI 2013, and we decided it would be instructive to include supporting

documentation within the scope of our project. Our group had read an abundance of

literature about how easy it is to inadvertently alter metadata when retrieving digital

materials from creators, and we knew we had to be extremely cautious in executing this

phase of the project.

Our initial plan was to schedule individual meetings with each AERI 2013 creator

and to securely retrieve their files using the write-blocker included in the Forensic Recovery

of Evidence Data (FRED) workstation. Unfortunately, we were unable to locate a USB Cable

to USB Cable (A to A) that would make the passage of files off a creator’s host machine,

onto an external storage device, and onto our workstation in the Digital Archaeology Lab a

completely secure pathway. That said, we were able to transfer files from a host machine

onto an external hard drive in a secure way, and to pull up files on our workstation while

keeping the write-blocker’s “read-only” settings activated. This allowed us to view

12

supporting documentation without altering vital metadata fields like date created. It was a

worthwhile learning experience to experiment with the write-blocker and to gain a sense

of how delicately one must proceed when retrieving materials from creators.

In-person transfer was not always a possibility. One creator, Sarah Kim, is based in

South Korea and retrieving her materials by email was our only feasible option. In addition,

Jane Gruning was unable to schedule an in-person meeting with us and did not have a

tremendous role in designing the website and elected to share her files with us over

Dropbox, a cloud-based file storage and transfer service. We were displeased to see that

Dropbox changed the “creation date” and “date modified” metadata fields of files and also

compressed files in an appreciable, but not significant way. Finally, we were able to grant

DSpace administrator, Dr. Patricia Galloway collection privileges that afforded her to ability

to upload all her supporting documentation, which might be the preferred mode of

transfer for any trusted digital repository.

Sarah Buchanan

Sarah Buchanan is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and was part

of the planning team for AERI 2013. Sarah created and edited content for the website,

organized and transcribed participants’ information, and kept minutes of the AERI 2013

planning meetings. Her materials were retrieved by Amye McCarther using a clean external

hard drive on April 9, 2014. These documents, which included MSWord documents and

MSExcel spreadsheets, were reviewed and any items containing confidential information

were removed. The remaining documents were then prepared for batch ingest (see

below).

Lorrie Dong

Lorrie Dong is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and was part of the

planning team for AERI 2013. She created the content for all of the non-CFP pages of the

website, including lodging, schedule, bios, and transportation maps. Materials were

retrieved from Lorrie Dong by Amye McCarther using a clean external hard drive on April

13, 2014. The documents were converted to a 7-zip file by Nicole Feldman on April 23,

2014. The zipped file contains MSWord documents, PDFs, MSExcel spreadsheets, Power

Point presentations, JPGs, GIFs, HTML, TXT and MNO documents. Two folders and one

spreadsheet were removed prior to the documents being zipped as they contained

confidential information.

13

Patricia Galloway

Dr. Patricia Galloway is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin School of

Information. She played a leadership role on the planning team for AERI 2013. Because she

is the administrator for the iSchool DSpace repository, we gave her submitter permission

to ingest documents into her creator collection.

Jane Gruning

Jane Gruning was part of the AERI 2013 planning team, but had a very minor role in

creating the website. She reviewed materials that went onto the site and helped form the

restaurant list. Her content was generated using a 2011 MacBook Air running Mac OS and

Microsoft Word and Excel 2008. Materials were retrieved from Jane Gruning by Jim Rizkalla

via DropBox April 13, 2014. The documents were converted to a 7-zip file by Nicole

Feldman on April 23, 2014. The zipped file contains four MSWord documents and one PDF

file. These files consist of drafts of application forms, programs and schedules.

Sarah Kim

Sarah Kim was a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and was part of

the planning team for AERI 2013. She initiated the @AERI2013 Twitter account for the

Conference Event and designed the official logos for the event and the website (which

were adopted by the institution hosting the 2014 AERI Conference). She also transformed

the text prepared by Sarah Buchanan for the program into a booklet PDF. Kim currently

lives and works in South Korea, so our group was restricted to receiving her materials

virtually. Materials were retrieved from Sarah Kim by Nicole Feldman via email on March

31, 2014. The files consist of various versions of the AERI logo in JPG and GIF formats.

Virginia Luehrsen

Virginia Luehrsen is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and was part

of the planning team for AERI 2013. She was involved in the early stages of planning and

designed the initial website, but played a diminished role after February 2013. Materials

were retrieved from Virginia Luehrsen by Lauren Gaylord and Jim Rizkalla using a clean

external hard drive on April 16, 2014. The documents were converted to a 7-zip file by

Nicole Feldman on April 23, 2014. The zipped file contains MSWord documents, MSExcel

spreadsheets, JPGs, PNGs, HTML and CSS documents and one MSAccess database file.

Two folders were removed prior to the documents being zipped as they contained

confidential information or duplicate files.

14

Katie Pierce Meyer

Katie Pierce Meyer is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin and was

part of the AERI 2013 planning team, though she had a very minor role in creating the

website. She contributed content to the website for the schedule and room assignments.

She also designed the AERI 2013 tote bag. Materials were retrieved from Katie Pierce

Meyer by Lauren Gaylord using a clean external hard drive on April 18, 2014. The

documents were converted to a 7-zip file by Nicole Feldman on April 23, 2014. The zipped

file contains MSWord documents, PDFs, MSExcel spreadsheets, Power Point presentations,

JPGs, PNGs, GIFs, TIFs, Bitmap images, HTML, PSD, AI, and EPS documents. Three folders

and two spreadsheets were removed prior to the documents being zipped as they

contained confidential information.

SECTION II: DEVELOPMENT OF ARRANGEMENT

Before working directly in DSpace it was necessary to develop the architecture of

the arrangement for our collection. Our primary goal in this project was to preserve the

AERI 2013 website, so naturally, that was selected as the first subcommunity in our

collection. This subcommunity contains archived components, aggregate versions, and

externally hosted content of the AERI 2013 website. The collections within the

subcommunity are the AERI 2013 Virtual Machine, AERI 2013 Website Component Files,

and AERI 2013 Website Externally Hosted Content. The AERI 2013 Virtual Machine consists

of the Virtual Machine Disk (VMDK) file that captures the virtualization of the AERI 2013

website. AERI 2013 Website Component Files consists of two items: the HTML pages

individually ingested, showing the functionality (as of April 2014) of the AERI 2013 website

created by UT doctoral students and faculty as well as, a .tar file of the public_html

directory of the AERI 2013 website. AERI 2013 Website Externally Hosted Content contains

nine items: KML Files of AERI 2013 Google Maps, Lorrie Dong AERI 2013 Flickr

Photographs, a Persistent html page of #aeri2013 tweets, Screenshot of AERI 2013 Flickr

Page, Screenshot of DIPIR Web Page, Screenshot of Lorrie Dong Web Page, Screenshot of

Sarah Ramdeen Web Page, Screenshots of AERI 2013 GoogleMaps, and Twitter

Screenshots.

The proceeding subcommunity captures our group’s efforts to archive the AERI

2013 Website. The AERI 2013 Website Project Documentation subcommunity consists of

15

documentation about the archiving of the 2013 website created by the 392K team

including SIP Agreements, project reports, and project notes.

Our group felt it would be instructive to also include supporting materials that

documented the creation of the AERI 2013 Website as well as the planning of the 2013

Conference Event. The AERI 2013 Website Supporting Documents subcommunity contains

supporting documents used during the creation of the AERI 2013 Website and the

planning of the accompanying conference. Collections are arranged according to creator

and maintained in the order received. There are seven collections in this subcommunity,

namely: Jane Gruning Materials, Katie Pierce Meter Materials, Lorrie Dong Materials,

Patricia Galloway Materials, Sarah Buchanan Materials, Sarah Kim Materials, and Virginia

Luerhsen Materials. Enough descriptive specificity was given to indicate whether a creator’s

role was more in the planning of the conference or more in the creation of the website.

SECTION III: INGEST OF MATERIALS AND METADATA

Accurate identification and description of digital objects is critical to their longevity.

For much of history archives have been populated with paper records which may remain

stable over long periods with little need of interference, and whose functionality depends

only on the durability of its material substrate and the fixity of any markings thereon. By

contrast, digital records are highly unstable and depend entirely on computing

environments in order for their contents to be interpreted in a way that is humanly

readable. Composed of bytestreams, literally sequences of magnetized and demagnetized

particles literally signifying 1s and 0s, these objects and the hardware and software

environments that support their creation quickly obsolesce. Without detailed metadata

about the file formats represented in these bytestreams and the environments that may

render them, the objects become opaque and unusable. Hence, while traditional records

archiving could allow a degree of inattention given the proper storage conditions, digital

records afford no such luxury.

In addition to serving the functional purpose of keeping digital objects usable,

metadata is also key to establishing authenticity. The evidentiary value of metadata has

been recognized in the digital forensics community and the same concepts can be applied

within archival practice. Metadata may be used to authenticate, track and safeguard digital

assets. The ease with which digital objects may be transferred or altered makes the

detailed and accurate collection of metadata regarding their original instantiation of

16

utmost importance. Digital objects are also vulnerable to invisible changes as they move

from one operating environment to another. Checksums may be used to mathematically

calculate the components of a digital object and, thus, are useful for validating that a

digital object has been transferred without change. Some file formats, such as BWF Wav

files, may have checksums embedded in the file itself while others require separate

documentation. Additionally, tools developed by the digital forensics community such as

write-blockers, can facilitate the transfer of digital objects between devices without

alteration.

DSpace is equipped to store and create many types of metadata about the objects

it ingests. These include metadata describing contents and creators as well as functional

aspects. DSpace currently borrows most of its qualifiers from the Dublin Core Libraries

Working Group Application Profile (LAP), which it adapts and appends as needed. Some

metadata fields are automatically populated by DSpace when items are ingested, such as

accession date and checksum values, while other fields may be entered manually or

harvested separately and ingested as a batch.

Once our team had identified the type and extent of the materials gathered to be

archived, we informed the UT DSpace administrator, Dr. Pat Galloway, of the MIME types

that were present in the collection so that DSpace could be prepared to ingest them. The

items comprising the AERI 2013 website, including KML files of the Google maps and live

content harvested from Twitter and Flickr, were ingested manually. In addition to these

documents a VirtualBox containing the .tar of the website and contemporary web

browsers. These together provide a virtualization of the website as most viewers would

have seen it while it was active, in anticipation of a time when those web browsers and

their rendering of web content will no longer exist. Narrative description of all of the file

types and the methods of their retrieval were provided for each item in addition to

identifying file formats in the appropriate DSpace field. The remainder of the project

documentation followed a similar methodology for description.

Supporting documentation was ingested by two means, batch ingest and manual

ingest of zipped file directories or individual items. A batch ingest was employed as a test

case. The smallest collection of materials was chosen for batch ingest, as so that any

problems occurring during the process could be quickly accounted for and amendments

made.

Preparation for the batch ingest involved a two-step process: harvesting metadata

and preparing documents for DSpace to ingest. The New Zealand Metadata Harvester was

downloaded to our workstation and used to extract XML metadata tags for each of the

17

items. While the process was performed quickly, the tags produced did not conform to the

Dublin Core schema used in DSpace. To produce the proper tags a spreadsheet was made

of the tag elements we selected to ingest with the items, with columns left blank between

tags to be populated accordingly. These values were populated using a combination of

narrative information from creators and metadata extracted using the New Zealand

Harvester. Each row was then concatenated and compiled as an XML document for each

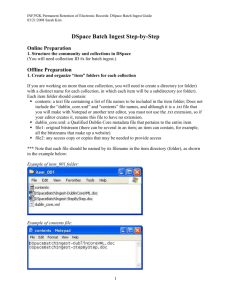

item. Batch ingest further requires that each item reside in a file titled item_000, item_001,

item_002, etc. and that each file contain the digital item, an XML document containing the

Dublin Core metadata tags entitled dublin_core.xml, and a TXT document containing only

the filename of the item and entitled contents. With the exception of one folder containing

other nested folders, all of the items prepared for the batch ingest were individual files. For

the folder a nested folder was removed due to confidentiality concerns and the remaining

contents were zipped to retain their structure.

Figure 1. Example of a directory prepared for batch ingest.

The batch ingest was conducted with the help of information technology

coordinator, Carlos Ovalle.

For the remainder of the supporting documents it was decided that manual ingest

would be used; however the number of these documents was deemed too unwieldy for

them to each be ingested individually. As with the folder in the batch ingest, the file

directories of each creator were zipped into 7-zip files and these 7-zip files were ingested

18

into their respective collections. The advantage to using this method was that the structure

of the file directories was maintained in the order received from the contributors,

providing evidence of the organization and file naming schemes employed by each.

Finally, documentation produced during the course of archiving the AERI 2013

website was zipped and submitted manually by members of the project group.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

Lessons and Recommendations

The paper backlog is a familiar obstacle, stymying the efficiency of archival

institutions, and has led to the widespread adoption of policies like “More Product, Less

Process” (MPLP). MPLP articulates that archival theory does not always neatly align with

archival practice, and that institutions should work towards an operational strategy that

best serves users. Similarly, the daily hurdles archivists working with analog materials face,

befall digital archivists, too. Accordingly, our group had to navigate the murky territory

between theory and practice throughout our efforts to archive the AERI 2013 website.

For example, the batch ingest process undertaken by our group proved to be very

time-intensive due to the incompatibility of the metadata tags exported by the New

Zealand Metadata Harvester with the DSpace metadata schema. As a result, tedious

copying and pasting of harvested values was necessary to prepare the ingest XML

document, and detracted from the amount of time our group had to complete other parts

of our project.

In a similar vein, one of the common types of problems we encountered during the

process was the unavailability of critical resources and dependency on other people.

Though we would have liked to gather all available supporting documents from their

creators with a write-blocker and external hard drive, in practice, this was not possible. We

were unable to locate a A to A USB cable (also known as male to male), which we required

to copy materials from the originating device to our external drive via a write-blocker. Due

to time constraints we proceeded without using the write-blocker to copy supporting

materials. Additionally, an external hard drive was not immediately available to us, delaying

the collecting of supporting documents. Another instance of lack of resources occurred

when we were unable to create a .tar file due to our accounts not being allotted enough

space on the iSchool server. Our group’s unfamiliarity with many of the technical processes

needed for our project also made us dependent on iSchool IT staff for command-line

functions and batch ingest processes.

19

Towards the end of our process of collecting supporting documents from creators,

we learned of the planning team’s use of the online project management tool Basecamp. It

was not universally adopted by the group and thus is an incomplete record of their

activities. While it would have been worthwhile to explore preserving the documentation

on Basecamp, time constraints prevented us from gathering and ingesting the materials.

Additionally, many members of the planning team found the tool cumbersome and

difficult to navigate, leading to its reduced use towards the end of the planning stages.

Many of the sixteen files uploaded to Basecamp were duplicated within the existing creator

collections, but the Writeboards contain information created within Basecamp and thus

not available anywhere else. The AERI 2013 Basecamp contains seven Writeboards and

allows users to review different revised states. Basecamp allows these boards to be

exported as HTML or TXT files, if they are considered worthy of preservation in the future.

A list of the files and Writeboards is included in Appendix 4 for reference. The late

discovery by our group of the Basecamp documentation speaks to the difficulties of

coordinating with a large group of creators. Few of the creators remembered the site’s

existence until prompted, and their frustration with it as a project management tool led

many to discourage its preservation. On the fly decisions, such as this, characterize the

exciting and challenging nature of digital archiving.

Conclusions for Future Web Archiving Projects

One of the biggest obstacles our group faced in completing this project was

overcoming our minimal technical knowledge. We primarily surmounted this setback by

working collaboratively with IT Staff at the iSchool, who were instrumental in seeing that

our project tasks were executed correctly. Going forward, our group feels that archivists

should adopt a like-minded collaborative attitude and elect to work symbiotically with IT

Support Staff as well as with web designers and web developers at their institutions. Simple

Linux commands like RSync, which were critical to our archival strategy are well known

within IT Support Staffs, and archivists serve to gain tremendously from working with these

individuals.

In addition, by working directly with web designers and web developers, archivists

can aid in making sure websites are designed to meet optimal archival benchmarks. Sites

like Archive Ready (see Appendix 3) generate comprehensive reports on a website’s

archival compatibility, and should be thoroughly engaged with before embarking on an

archival project. While our group enjoyed the imagination required to capture widgets, we

would recommend that future website archiving projects not devote considerable

20

resources or time to these endeavors unless the content hosted on these items is

completely essential to the underlying archival mission.

21

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Inventory of website file directory

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5486 Jun 1 2013 about.html

16 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

12419 May 14 2013

AERI_2013_PAYMENT_FORM.docx

72 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

67056 Apr 15 2013

AERI2013_PreliminaryProgram.pdf

1328 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users 1353967 Jun 12 2013 AERI2013-Program.pdf

72 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

66014 Apr 30 2013 AERI2013_Week-at-a-

Glance.pdf

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5731 Sep 13 2010 aeri2.css

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5721 Sep 6 2010 aeri3.css

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5338 Sep 8 2010 aeri4.css

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5451 May 20 2013 aeri.css

316 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

317050 Jun 25 2013 AERIgroup.JPG

32 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

28689 May 20 2013 AERI-logo-bold.jpg

16 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

13498 Jun 1 2013 AERI-logo-web.gif

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4566 Nov 28 2012 aeri.png

68 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

63488 Dec 26 2012 application.doc

148 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

145917 Jun 3 2013 bios.html

24 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

22956 Apr 29 2013 Briscoe.jpg

44 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

43520 Dec 27 2012 chair.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1407 Dec 26 2012 chair_guidelines.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1274 Dec 26 2012 chair_guidelines.html

28 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

25172 Apr 18 2012 CHIPS.jpg

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4303 Jun 3 2013 doctoral_proposal.html

36 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

34069 Dec 17 2012 EASP_Application_2013.docx

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

7687 Jun 3 2013 emerging_scholars.html

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

6689 Jun 3 2013 explore.html

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4662 Jun 3 2013 faculty_proposal.html

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

3995 May 21 2013 follow_bird-b.png

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

3090 May 11 2013 food.html

22

4 drwxr-xr-x 2 lgaylord users

4096 Apr 1 2013 forms

170400 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users 174313472 Jun 18 2013 HRC-Mamlet1931-video-2013-0617-Kim.mp4

28 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

27170 Apr 3 2013 IMLS_logo.jpg

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4465 Jun 25 2013 index.html

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4016 Jun 3 2013 info.html

12 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

8236 Apr 29 2013 iSchool.jpg

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5114 May 11 2013 lodging.html

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4669 May 20 2013 meeting.html

48 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

45568 Dec 27 2012 mentor.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1774 Dec 27 2012 mentor_guidelines.html

44 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

44544 Dec 26 2012 paper_poster.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1318 Jan 31 2013 paper_poster_guidelines.html

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5407 Jun 3 2013 proposals.html

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

3184 Jun 3 2013 registration.html

28 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

27030 Jun 16 2013 schedule.html

36 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

33280 Dec 26 2012 scholarship.doc

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

4357 Jun 3 2013 scholarships.html

12 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

11137 Apr 3 2013 SJH bathroom.jpg

16 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

12490 Apr 3 2013 SJH bed.jpg

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

105 Apr 30 2013 top.gif

8 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

5741 May 8 2013 transportation.html

16 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

15367 Jun 11 2013 travel.html

136 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

134546 May 14 2013

UT_PAYEE_INFORMATION_FORM.pdf

56 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

51712 Dec 27 2012 workshop.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1262 Dec 26 2012 workshop_guidelines.doc

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1224 Dec 26 2012 workshop_guidelines.html

4 -rw-r--r-- 1 lgaylord users

1224 Dec 26 2012 workshop_guidelines.txt

4 drwxr-xr-x 2 lgaylord users

4096 May 20 2013 zzz

23

Appendix 2: JQuery Script to Output #AERI2013 Tweets

$('.content').map(function(i, el) { return { #AERI2013: $(el).find('.fullname').text(), tweet:

$(el).find('.tweet-text')[0].innerHTML } })

24

Appendix 3: Archive Ready Report

25

Appendix 4: Basecamp Documentation

Writeboards:

AERI Workshops – categories

General notes – Katie

Groups

Schedule for the Week

Schedule for the Week – another option

Student day schedule – Wednesday

Workshop idea: Promotion and Advancement

Files Uploaded:

AERI-banner-Kim-small.jpg

AERI-master-black.tif

AERI-logo.gif

AERI-master.tif

HRC-Hamlet1931-video-2013-06-17-Kim.mp4

AERI_Program.doc

AERI_2013_Schedule_feb25.doc

Expenses list for AERI 2012.xlsx

CFP_aeri2013.doc

ABOUT AUSTIN.docx

AERI_Travel_website.doc

Austin-Restaurants.docx

AERI Application Form - Draft 1.doc

AERI WORKSHOPS.docx

Timeline for Preparing AERI 2012.doc

To-do for AERI 2013 planning.xlsx

26

Works Cited

January 2013 White Paper entitled, “Update on the Twitter Archive At the Library of

Congress.” Accessed on April 12, 2014 at

http://courses.ischool.utexas.edu/galloway/2014/spring/INF392K/LOC_TwitterReport

_2013jan.pdf