ApPARENT

advertisement

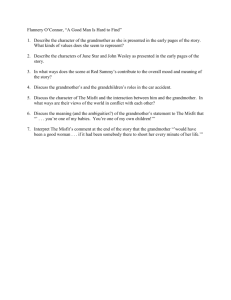

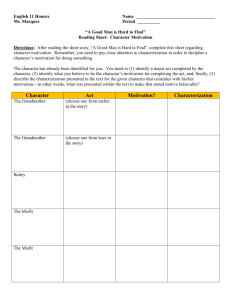

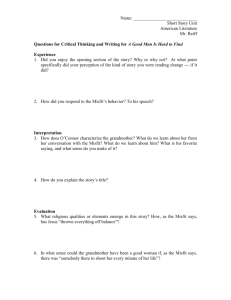

Lucy Santora ApPARENT John Paul II High School Faculty Sponsor: Heather Cernoch (heathercernoch@johnpauliihs.org) ApPARENT How is humanity defined by filial piety? How can the future reap experience from its predecessors? How is society a product of its makers? Flannery O’Connor attempts to answer these questions by exploring the foibles of human nature through character dialogue in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” cautioning readers that parenting plays a vital role in the development of a person’s concept of morality. The aspect of disrespectful children is illustrated in the early pages of the story by the sarcastic tone of June Star and John Wesley as they snap at adults in the story. When the grandmother expresses her apprehensions about traveling to Florida, John fires back a short retort saying, “If you don’t want to go to Florida, why dontcha stay home?” (O’Connor) June Star plays off this jest with extreme exaggerations that their grandmother wouldn’t let the family go anywhere without her even if offered to “be queen for a day” or “a million bucks.” O’Connor employs short syntax and hyperbole in order to highlight the spoiled nature of the children. She further develops the children’s lack of appreciation through their remarks during the trip to Florida. John refers to Tennessee as a “hillbilly dumping ground” and Georgia as a “lousy state.” This reflects the opinions his parents exposed John to and the absence of a filter, which his parents neglected to develop. If their parents had instilled better values and demanded more respect from their children, John and June would not act out in such a disgraceful manner. At Red Sam’s June refers to the restaurant as “a broken-down place” in front of Red Sam’s wife. Again, Bailey says nothing, letting such insubordinate behavior slide for the time being, even when his mother asks him, “Aren’t you ashamed?” The grandmother projects a strong sense of respect, yet there is disconnect in this attribute since it is not passed to her son. Here O’Connor points out that it does not matter if one’s parents are good people; what matters is that parents teach their children strong values and morals. Soon after they are on the road again, the children kick and scream their way into getting to make an extra stop to see an old plantation, claiming they “never do what they wanted to do.” O’Connor tries to show that the children learn they can manipulate their way into getting what they want, they are above social courtesies, and their actions have no consequences. The Misfit and his accomplices, whose consciences lack a general respect for others, exhibit the negative outcomes of children whose upbringing doesn’t mold them in the aspects of right and wrong. Bailey, the impatient husband and son of the grandmother, is a symbol of unnecessary agitation and its catastrophic implications, and he is definitely the source of his kids’ lack of respect. He continually disregards his mother’s opinion and treats her as a nuisance—a bee that won’t stop buzzing. When his mother warns him against traveling through an area with a criminal on the loose, Bailey doesn’t even acknowledge that she speaks. Here O’Connor inserts her dark humor; if Bailey had listened to his mother or inquired more about the whereabouts of the criminal, he may have assessed the situation better and avoided the murder of his entire family. The outcome is indeed grotesque and dark, but it was avoidable. It is also possible that if Bailey wasn’t so easily annoyed his mother would have shared her desire to bring Pitty Sing along for the trip instead of attempting to hide the cat. A proper discussion would have at least made Bailey aware of the cat’s presence and could have prevented the crash. O’Connor points out that belittling someone’s opinion can result in having a hard time “answering to one’s conscience.” However, Bailey is not entirely to blame for this exchange between mother and son. One can easily point to the flaws of Bailey’s mother in his upbringing. Bailey lacks the tender qualities his children also lack; he is disrespectful and insensitive. O’Connor uses the voice of the grandmother to present that people are not of a singular character but rather a quilt-work of multiple traits. In the opening conversation with her son, the grandmother comes across as overbearing and stubborn. She rants about The Misfit on the loose and how their family could become the victims of his atrocities, conjuring an image within the reader of the “grandma from the other side of the family.” As aforementioned, the grandmother’s family group is unruly. The grandmother fails as a parental figure two-fold, once with Bailey and once again with her grandchildren. Despite her efforts, she is unable to command respect. The reader has a sense of pity for the grandmother, who is abused by her family’s sarcasm and disdain. Paradoxically, the reader is also annoyed with the grandmother, who can’t seem to say or do the right thing in any given scenario. The grandmother is unable to convince her son of her concerns, makes a poor choice by sneaking Pitty Sing along for the trip, and even uses her grandchildren’s poor behavior to manipulate her own son into driving where she wants. The first flaw alludes to a strained mother-son relationship while the second demonstrates the grandmother’s sense of self-importance; she wants to bring the cat and thus the opinion of the family doesn’t matter, and her want is her action. The latter flaw shows the grandmother adapting to the nature of her younger relatives. They taught her how to play their game of pushing buttons and applying just enough innocent pressure so they can achieve their desired outcome. O’Connor demonstrates that humans are susceptible to error, but the grandmother is the beacon of good intentions with poor execution. The Misfit, too, is, for lack of a better term, a product of bad parenting. His conscience is detached from his actions, and consequently, he sees human life as without intrinsic value. During his conversation with the grandmother, the old woman, trembling with fear, says, “You wouldn’t shoot a lady, would you?” to which he responds, “I would hate to have to.” This shows that there is, indeed, a shred of his heart susceptible to the pain of wrongdoing, yet it is not strong enough to prevent him from engaging in such action. When the grandmother proclaims, “I know you’re a good man,” the Misfit answers, “I ain’t a good man.” This shows that The Misfit has a sense of what is right and what is wrong—at least enough to assess that his actions fall into the latter category, yet he takes no measures to alter his destructive course. Why would he neglect what he knows is righteous to engage in wrongdoing? The Misfit briefly mentions his parents, specifically his absentee father. He discusses that his father had a “way with the law” and was able to “deal with authority.” This points to the criminal nature of his father and that this was the primary role model in the Misfit’s formative years. Unlike the grandmother, the Misfit’s father did exceptionally well in passing on his finer attributes. Unfortunately, the definition of “finer” is in the eye of the beholder. O’Connor uses this moment to shed light on the position of a role model in a child’s formation of character. The Misfit obviously took his father seriously, believed him to be royalty, and consequentially took the path he outlined. On the other hand, Bailey viewed his mother as an overbearing nuisance, didn’t waste a breath on listening to her wisdom, and thus matured without her qualities of respect and courtesy. This chain continues from Bailey down to June Star and John Wesley. Like the Misfit, they idolize their father. When they see their father condescending his mother, they believe they can—or even should—act in the same manner. The human species is geared toward adopting traits from our experience with important figures in our lives. O’Connor’s purpose is to address this issue and caution against becoming stagnant in our social knowledge. She warns that society must pause and look into itself to assess its character with regard to what portion of it is a conscious choice and what part of it is mere muscle memory formulated by parental influence. Those who are carbon copies of their parents, in both positive and negative aspects, don’t realize it until they are at gunpoint. O’Connor uses this exhibition of family bickering and dark comedy to portray the importance of creating character based on individual definitions of morality instead of wearing the definition your mother gave you. Works Cited O’Connor, Flannery. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” A Good Man Is Hard to Find. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 Oct. 2014.