Class #3 - 6/24/13

advertisement

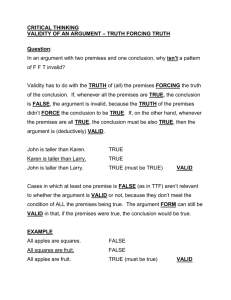

Philosophy 1100 Title: Critical Reasoning Instructor: Paul Dickey E-mail Address: pdickey2@mccneb.edu Website:http://mockingbird.creighton.edu/NCW/dickey.htm Today: Editorial Essay #1 Due. Next class (6/24/13): New Portfolio Assignment & Submit your Portfolio for review by Instructor Reading Assignment: Chapters Six and Seven 1 Student Portfolios: Assignment #3 How do I know an argument when I see it? How do I evaluate it? How does Relevance play in this? Collect from your daily experience 2-3 “artifacts” that describe your identification of an argument in your daily life, either one you made yourself or one you observed from someone else. · For each, write a description or explanation of the artifact selected and how you evaluate the argument for yourself. (1 paragraph) · Write a brief assessment of the relevance of your anecdotes chosen in Section Two of your portfolio to that topic. · Chapter Two Review Two Kinds of Reasoning The Fundamental Principle of Critical Thinking is The Nature of an Argument • Making a claim is stating a belief or opinion -- the conclusion • An argument is presented when you give a reason or reasons that the claim is true. -the premise(s) • Thus, an argument consists of two parts, and one part (the premise or premises) is/are the reason(s) for thinking that the conclusion is true. What is a Factual Claim? • A claim is sometimes called an assertion, an opinion, a belief, a “view”, a thought, a conviction, or perhaps, an idea. • A claim must be expressed as a statement or a complete, declarative sentence. It cannot be a question. • In its clearest form, a claim asserts that something is true or false. That is, it asserts a fact. This kind of claim is known as a “factual claim” or a “descriptive claim.” What is a Normative Claim? • Value statements can also be claims though. In such claims, a fact is not asserted in the same sense that it was in factual claims. • For example, the claim “You should come to class” is not true or false (at least in the same way that the claim “P1100 class is held in Room 218” is). • Thus, some claims are “normative claims” or “prescriptive claims.” They express values and how one should act based on values. A value statement is a claim that asserts something is good or bad. Now, Critical Thinking is Absolutely Relevant to Both Sets of Claims • As we shall see in this class, it is necessary that we identify very clearly which kind of a claim we have before we can properly evaluate any argument for it! • Thus, please note we are taking a position against the subjectivist and saying that even moral judgments can be analyzed by the principles of critical thinking. Arguments & Subjectivism • The view that “one opinion is as good as another,” “it’s true for me though it might not be true for you” or “whatever is true is only what you think is true” is known as subjectivism. • For some things, this makes sense, e.g. Miller taste great. My grandson is cute. The waiter at the restaurant was nice. • Your text refers to these as “subjective claims” and says that “some people” (but presumably not critical thinkers may call these “opinions.”) Two Kinds of Good Arguments • A good deductive argument is one in which if the premises are true, then the conclusion necessarily (that is, has to be) true. • Such an argument is called “valid” and “proves” the conclusion. • For example – Lebron James lives in the United States because he lives in Nebraska. All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. ____ Socrates is mortal. • A sound argument is a valid, deductive argument in which the premises are in fact true. How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Deductive argument, premises prove or demonstrate a conclusion based on if the premises make the conclusion certainly true. Consider the argument: (P1) If it’s raining outside, the grass near the house gets wet. (P2) It’s raining outside. _________________________ The grass near the house is wet. In a Deductive argument, premises prove a conclusion based on the logical form of the statement or based on definitions. It would be a contradiction to suggest that the conclusion is false but the premises are true. Two Kinds of Good Arguments • A good inductive argument is one in which if the premises are true, then the conclusion is probably true, but not always. The truth of the premises do not guarantee the truth of the conclusion. • Such an argument is called “strong” and supports the conclusion. • For example: Dan lives in Nebraska and he loves football, so he is a Nebraska Cornhusker fan. If offered to me before class tonight, I would have made a bet with my wife that each of you would sit in the same seat in class that you did last week. If she would have taken the bet, would I have won more money than I would have lost? What is “Beyond a Reasonable Doubt” vs “Proof? • Although standard English usage is often lax about this, technically speaking, PROOF requires a valid deductive argument. • “Beyond a reasonable doubt” requires a level of evidence in an inductive argument such that if someone were to believe it were not true, they might still possibly be right, but that probability is so remote that reasonable, critical thinking, people will be satisfied to act and claim to know without a proof. How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Inductive argument, premises support (never prove) a conclusion based on how strongly the premises provide evidence for the conclusion. Consider the argument (Variation One): (P1) When it rains outside, the grass near the house only gets wet when the wind is blowing strongly from the North. (P2) The wind usually blows from the South in Omaha. ________________________ Even though it is raining, the grass near the house is not wet. How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Inductive argument, premises support (never prove) a conclusion based on how strongly the premises provide evidence for the conclusion. Consider the argument (Variation Two): (P1) When it rains outside, the grass near the house always gets wet when the wind is blowing strongly from the North. (P2) In Omaha, the wind usually blows from the South. (P3) Today the wind is blowing from the North. ________________________ The grass near the house is wet. How Do Premises Support Factual vs. Normative Conclusions? In regard to evaluating Inductive support for Factual vs. Normative Conclusions, I would suggest the following two tips to keep in mind 1) Only Factual Premises support Factual Conclusions. That is, if the conclusion is factual (or descriptive), ALL premises must be factual. 2) A Normative Premise is always needed to support a Normative Conclusion. That is, if the conclusion is normative (or prescriptive), there must be at least one normative premise. Of course, there may or may not be factual premises! Chapter Three: Vagueness & Ambiguity 16 Vagueness • A vague statement is one whose meaning is imprecise or lacks appropriate or relevant detail. “Your instructor wants everyone to be successful in this class.” “Your instructor is bald.” • Vagueness is often evident when there are borderline cases. Problem is not so much what the concept is but what is the scope of the concept. (e.g. baldness) • Some assertions may be so vague that they are essentially meaningless (e.g. “This country is morally bankrupt,” but most concepts though vague can still be useful. 17 Vagueness • A critical thinker will first want to clarify what is being asserted, even before asking about what are the reasons to believe or what is the evidence. • The more precise or less vague a statement is the more relevant information it gives us. a. Rooney served the church his entire life. b. Rooney has taught Sunday School in the church for thirty years. a. The glass is half full with soda pop. b. I poured half of a 12 oz can of soda pop into the empty glass. 18 Vagueness • What detail is appropriate depends on audience or the issue. It can be difficult to determine. Compare your friend calling you after reading an article in the paper about mortgage rates and telling you that you should expect to pay higher rates vs. your bank calling you and telling you that your mortgage rate is going up. You are at your neighbor’s for a BBQ and you ask him, “So how big is your yard? How far does the property line go to? “ He says “Oh, right behind the trees.” This is probably a good answer. But now you are thinking about buying his home and you ask the real estate agent the same question. You will not be satisfied with his “vague” answer. 19 Vagueness • Vagueness at times is intentional and useful. 1) Precise information is unavailable and any information is valuable. “This word just in. There has been a shooting at the Westroads Mall and there may be fatalities. More information will be forthcoming as soon as available.” 2) Precise information will serve no useful function in the context (yes, even in a logical argument!) Rarely, if ever, at a funeral, does a minister remind the grieving family that their father only attended church infrequently and showed no interest in his family attending. Ministers who would do such a thing would probably be considered jerks. 20 Vagueness in a Logical Argument • The bottom line in the context of analyzing or proposing a logical argument, a claim is vague when additional information is required to determine whether or not a premise is relevant. • Such vagueness is always a weakness and effort must be taken to avoid it. It is generally considered to be “hiding the evidence” when it is done intentionally. • You remove vagueness by adding the relevant detail. 21 Ambiguity • A statement which can have multiple interpretations or meanings is ambiguous. • Examples: “Lindsay Lohan is not pleased with our textbook.” “The average student at Metro is under 35.” “Jessica rents her house.” “Alice cashed the check.” “The boys chased the girls. They were giggling.” 22 Ambiguity • Of course, ambiguities can be obvious (and perhaps rather silly) “The Raider tackle threw a block at the Giants linebacker.” “Charles drew his gun.” • In these cases, we are not likely to be confused. The context tells us more or less what is meant. However, it should be understood that it is often not good to assume our audience will always have the same knowledge, orientation, and background that we do. 23 Ambiguity • Carmen's Swimsuit Switcheroo Frequently a logical argument is sabotaged by a person switching meanings in the middle of an argument. This is known as equivocation. We all know what we mean by “subjective” in this class, but we need to be sure that the term is used consistently and not switch to one of the other meanings in the middle of a a discussion. 24 Ambiguity • • Ambiguities can also be quite subtle, e.g. “We heard that he informed you of what he said in his letter.” • One ambiguity here is whether the person (the “you” in question) received a letter at all. Did “he” inform “you” of what he said but only we saw a letter to that affect, thus “we heard in his letter (to us),” or did “we hear” that within a letter “you” were informed and we heard that you were informed by means of a letter to “you”? • Such a point might seem tedious, but could in fact legally be very significant. Actually, Bill Clinton had a point when he said “It depends on what the meaning of is is.” e.g. Are you having a fight with your husband? 25 Ambiguity • Keep in mind that ambiguity, like vagueness, is at times intentional and often is useful. 1) Clever uses of “double meaning” can catch our attention and entertain us or provoke us to consider the claim more carefully. “Tuxedos cut ridiculously.” “You can’t pick a better juice than Tropicana.”’ “Don’t freeze your can at the game.” “We promise nothing.” 26 Ambiguity in a Logical Argument • The bottom line is that in the context of analyzing or proposing a logical argument, ambiguity is always a weakness and effort should be taken to avoid it. • If you use it for “effect,” you should be absolutely sure that the claim and your premises are clear to your audience. 27 Ambiguity • Please note that while with the case of vagueness, we resolved it by adding information that clarified meaning, with the case of ambiguity what we are interested in is to eliminate the suggestion of the potential alternate meaning that we do not desire. • “The Raider tackle threw a block at the Giants linebacker.” We want to eliminate the possibility that one could think that one is “throwing a block (of wood?)” Thus, we can say “ The Raider tackle blocked the Giant’s linebacker.” 28 Ambiguity • Let’s discuss three kinds of ambiguity. 1. Semantic ambiguity is where there is an ambiguous word or phrase, e.g. “average” price. -- When Barry Goldwater ran for president, his slogan was, "In your heart, you know he's right." In what way is this ambiguous? 2. Syntactic ambiguity is where there is ambiguity because of grammar or sentence structure, e.g. --“Players with beginners’ skills only may use Court #1.” 3. Grouping ambiguity is ambiguous in that the claim could be about an individual in the group or the group entirely, -- Baseball players make more money that computer programmers.” (fallacy of division) 29 Defining Your Terms • Defining terms helps one avoid vagueness and ambiguity. Video • Sometimes you need to use a stipulating definition if perhaps you are using a word in an argument in a different way than it is usually understood or it is a word in which there is itself some controversy. • It is frequently quite reasonable in a logical argument to accept a stipulating definition that you would not yourself have chosen, but does not pre-judge the issue and allows the discussion to precede without distractions. 30 Defining Your Terms • Most definitions are one of three kinds: 1. 2. 3. Definition by example. Definition by synonym. Analytical definition. • Any of these might be appropriate. • Be careful of “rhetorical” definitions that use emotionally tinged words to pre-judge an issue. • Do not allow someone in an argument to use a “rhetorical definition” as a stipulative definition. If you do, the argument will likely be pointless and subjective. 31 Chapter Five: Persuasion Through Rhetoric • Rhetoric tries to persuade through use of the emotional power of language and is an art in itself. • Though it can be psychologically influential, rhetoric has no logical strength. • Rhetoric does not make your argument any better, even if it convinces everyone. • Can you recognize rhetoric? Euphemisms and Dysphemisms • A euphemism attempts to mute the disagreeable aspects of something. • If I say a car is “pre-owned,” does that sound better and a person would be more likely to buy it than if I said the car was “used?” There is no logical difference. it is the same car. • Would you be more willing to support a “revenue enhancement” or a “tax increase”? Euphemisms and Dysphemisms • Fox news put out an internal memo to its staff to refer to U.S. servicemen in Iraq as “sharpshooters” not “snipers.” • Often, we try to make something “politically correct” by using euphemisms. • I would suggest perhaps a better strategy might be to identify clearly and logically analyze biases and thus we would likely discard them. • Oppositely, a dysphemism attempts to produce a negative association through rhetoric. • How do you feel about “freedom fighters?” How do you feel about terrorists? Often, the difference is only based upon which side you are on. • Please note that it is NOT a dysphemism to state an objective report that just sounds horrible, e.g. “Lizzy killed her father with an ax.” Analogies • An analogy is a form of reasoning in which one thing is inferred to be similar to another thing in a certain respect, on the basis of the known similarity between the things in other respects. • An argument from analogy involves the drawing of a conclusion about one object or event because the same can obviously be said about a similar object or event. • An argument from analogy can be a good inductive argument that supports its conclusion. • The strength of any argument from analogy largely depends on the strength and relevance of the employed analogy. Rhetorical Deceptions & Dirty Tricks • But a rhetorical analogy attempts to persuade by use of a comparison (often clever and humorous) without giving us an argument. Hilary’s eyes are bulgy like a Chihuahua. Dick Cheney has steel in his backbone. Social Security is a Ponzi scheme. Video Definitions • An honest definition attempts to clarify meaning. A rhetorical definition uses emotionally tinged words to elicit an attitude that is vague (often intentionally) and pre-judges the issue. Bill Maher’s defined a conservative as “one who thinks all problems can be solved either by more guns or more Jesus.” Abortion is the murder of innocent, unborn children. Rhetorical Explanations • A rhetoric explanation is similarly deceptive and attempts to trash a person or idea under a mask or pretense of giving an explanation. • The War in Vietnam was lost because the American people lost their nerve.” • Students who drop my classes do so because they are idiots. • Liberals who criticize the U.S. Army’s actions in Iraq do so only because they are disloyal to their country. Stereotypes • A stereotype is used when a speaker groups multiple individuals together with a name or description, suggesting that all members of the group are the same in some basic way. •e.g. women are emotional, men are insensitive, gays are effeminate, lesbians hate men, Black men are good at sports. • Stereotypes are not supported by adequate evidence and ignore the psychological principle of individual differences. Stereotypes • People who do not think critically often accept stereotypes because of limited experience. •Tiger Woods and Michael Jordan are good at sports. Thus,…. • Stereotypes typically originate and become popular because of a cultural agenda (e.g. economic privileges) and in a environment of ignorance. Native American tribes of the Great Plains were generally considered noble people by most white Americans until it became economical advantageous to confiscate their lands. Most individuals of the early 20th century who harbored biases against Native Americans and African-Americans knew very few personally or knew them only in specifically defined roles. Stereotypes are often manipulated as propaganda to incite a nation to support a war or actions during time of an emergency crisis. • Hitler’s use in WWII of ethnic propaganda not only was against Jews, but also Blacks, gypsies, but certain other religious groups. • In the United States, we re-located Japanese families on the West Coast. • Some people believe today that the tea-party protests against the health care bill are manipulations for racist agendas (based on stereotypes). But careful, do you have GOOD PREMISES to believe either that they are or they are not? Innuendo • An innuendo is a deceptive and veiled suggestion or a slanting device applying negatively to an opponent’s character or reputation or to insert a claim though which a direct statement of the claim is avoided (perhaps because there is no evidence). • e.g. “Ladies and gentlemen, I am proof that there is at least one candidate in this race who does not have a drinking problem.” • Please note that in an innuendo the statement given will typically be absolutely true. Innuendo • The innuendo is based on the expectation that the reader will “read into” the statement something more than what is actually said, possibly thus making unwarranted assumptions about why the speaker may have said it. In this case, the speaker wants the listener to believe without giving evidence that there is some reason to believe that one or more of his opponents has a drinking problem. Innuendo • Did President Bush in his 2003 State of the Union address claim that Saddam Hussein was responsible for the 9/11 terrorist attack? • Or did he only “say” that Saddam in general sponsored terrorists? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rgwqCdv3YQo&feature=related The Loaded Question • A loaded question is a question that suggests strongly an unwarranted and unjustified assumption. • e.g. Do you still hang around with petty criminals? Have you stopped beating your wife? Why have you not renounced your earlier crimes? When are you going to stop lying to us? • This technique is often used quite intentionally in police interrogations to get a suspect to confess to acts that the police have no evidence for. Weaseling • Weaseling protects you from criticism by watering down your claim. • e.g. What if I would have previously said, “Probably most individuals of the early 20th century who harbored biases against Native Americans and African-Americans knew very few personally?” • If so, would have my statement been a good premise? No, not much. If you questioned it, I have a “way out.” Thus, it seems to lack much meaning. Weaseling • Weaseling is a method of hedging a bet. You can sometimes spot weaseling by an inappropriate and frequent use of qualifiers, such as “perhaps,” “possibly,” maybe,” etc. • Be careful. qualifiers also are used often to carefully say what can legitimately be said about an issue and are not weasel words. You need to assess the context carefully. Weaseling • Three years later, does President Bush “weasel” on his earlier justification for the Iraq war or does he “clarify?” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKd71JxEYzE Minimizing or Downplaying • Words and devices that add no argument but only suggest that a source or a claim is less significant than what the claim or premises suggest is called downplaying or minimizing, e.g. Are you going to vote for a “hockey mom?” Or “just another liberal?” • You can sometimes spot this by a use of words or phrases like “so-called,” “merely,” “mere,” or “just another.” • Downplayers often also make use of stereotypes. “That’s just Dick Cheney” Ridicule / Sarcasm • Ridicule and sarcasm is a powerful rhetorical device (often called The Old Horse Laugh Fallacy). • Keep in mind that it adds absolutely nothing to the logical force of an argument. • Questioning the “intelligence” of the person that makes a claim is logically irrelevant to whether the claim itself is true or false. Video Ridicule / Sarcasm • • It is interesting after watching a spirited debate (for example, one of political candidates) to analyze whether the person who came off more “humorous” or “entertaining” and the one whom we might have thought “won” the debate actually took advantage of his opponent unfairly through this method. If so, we should re-examine ourselves whether we were thinking critically during the debate. Video Hyperbole • Hyperbole basically means exaggeration or an extravagant overstatement. • e.g. “My boss is a fascist dictator. He won’t let anybody do things their own way. It is always his way or the highway.” • This kind of statement, considered for exactly what it says, is silly and lacks credibility. Hyperbole • Interestingly, hyperbole often works even when no one believes it. In this example, we probably don’t believe the statement is actually true, but we would probably be reluctant to take a job working for this guy thinking something like “where there’s smoke, there must be fire.” • Be careful: As critical thinkers, we have no more reason to believe the claim that the boss is a problematic one to work for than we do to believe the hyperbole. • BREAKING NEWS! Proof Surrogates • A proof surrogate is an expression that suggests that there is evidence or authority for a claim without actually citing such evidence of authority. • e.g. “informed sources say,” ”it is obvious that” or “studies show” are typical proof surrogates. • Proof surrogates are not substitutes for evidence or authority. Proof Surrogates • The introduction of a proof surrogate does not support an argument. • They may suggest sloppy research or even propaganda. • The use of proof surrogates, on the other hand, should not be interpreted that evidence does not exist or could not be given. You just don’t know. Never drive in a storm without wiper blades. & Never go into the fierce storms of an argument without your WIPER SHIELD to protect you from the evil forms of rhetoric devices: W easeling, I nnuendo, P roof Surrogates E xplanations, Analogies & Definitions (Rhetorical) R idicule/Sarcasm S tereotypes H yperbole I mage Rhetoric E uphemisms/Dysphemisms L oaded Questions, and D ownplaying/Minimizing