lecture powerpoint slides

advertisement

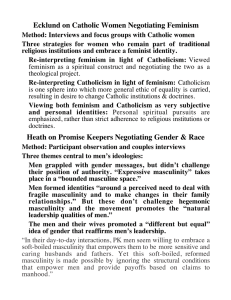

Feminism, Masculinity, and Gender Dr Chris Pearson Lecture outline • Gender history • Femininity and feminism • Masculinity Gender history: An overview • Associated with postmodernism • Gender identities are fluid and historical – they change over time • Against biological determinism: “nothing about the body determines univocally how social divisions will be shaped” Joan Scott, ‘Gender: a useful category of historical analysis,’ in Shoemaker and Vincent (eds.), Gender and History in Western Europe, (1998), 2 ‘“Man” and “women” are at once empty and overflowing categories. Empty because they have no ultimate, transcendent meaning. Overflowing because even when they appear contain to be fixed, they still within them alternative, denied, or suppressed definitions.’ Joan Scott, ‘Gender: a useful category of historical analysis,’ in Shoemaker and Vincent (eds.), Gender and History in Western Europe, (1998), 61 Histories of masculinity • White, European masculinity constructed against “outsider” males, such as Blacks and Jews George L. Mosse, The Image of Man, The Creation of Modern Masculinity (1996) • Masculinities “come into existence at particular times and places and are always subject to change.” R. Connell, Masculinities (1995), 185 Gender relations • Masculinity and femininity exist and change in relationship to each other • Masculine and feminine identities are “not… distinct and separable constructs, but… parts of a political field whose relations are characterized by domination, subordination, collusion and resistance.” Michael Roper and John Tosh (eds), Manful Assertions: Masculinities in Britain since 1800 (1991), 8 The “new women” The ‘new women was most commonly represented as a dangerous creature, masculinsed but man-hating, emancipated politically and sexually, a perversion of the natural order of things and a threat to morality and civilisation itself.’ James McMillan, France and Women, 1789-1914 (2000) 142 Mademoiselle Ly – a “new women” ‘As a women who fashioned her identity around her professional accomplishments and her call for women’s political and sexual emancipation, she subverted the traditional domestic image of the honorable woman.’ Andrea Mansker, ‘Mademoiselle Arria Ly Wants Blood!’ French Historical Studies 29:4 (2006), p.630 Changes to women’s lives during the belle époque • Republican expansion of education in the 1880s e.g. Camille Sée’s law of 1880 introduces female secondary schools • More and more women enter university; 2,772 French women enrolled at the universities by 1911-12, a twentyfold increase from the 1889-90 period. (Mansker, p. 639) Professional women • Teachers; 57,000 female teachers by 1906, almost 50% of the profession • Office and clerical work for banks, railway companies etc • By 1914, 30% of the female workforce were employed offices and department stores • McMillan, France and Women, 148-9 Marie Deraismes (1828-1894) Léon Richer (1824-1911) Gradualist, liberal feminism ‘Feminism could best advance by making small dents in the hard wall that patriarchy had constructed against women’s claims. The feminist’s task was to locate the loose brick and hammer against it. It was a realpolitik.’ Claire Goldberg Moses, French Feminism in the Nineteenth Century (1984), 199 Richer on the family: ‘Since man alone was enfranchised he alone moved on. Woman, his daily companion, excluded from this benefit, stayed behind, and within the passing of half a century an enormous distance, an abyss, inexorably divided the two sexes. Out of this division was soon born, within the heart of families, irreparable dissatisfaction, ruptures that one had not suspected.’ Quoted in Moses, French Feminism in the Nineteenth Century, 201 Women not ready for the vote, according to Richer: ‘I believe that at the present time it would be dangerous – in France – to give women the political ballot. They are in great majority reactionaries and clericals. It they voted today, the Republic would not last six months.’ Quoted in James McMillan, Housewife or Harlot (1981), 84 Hurbertine Auclert (1848-1914) Hurbertine Auclert, speaking in 1876: ‘In spite of the benefits that came from our revolution of 1789, two kinds of individuals are still enslaved: proletarians and women. Women proletarians have an even more deplorable fate... We have no rights. As interested as we may be in the happiness of our country, we are pitilessly turned away from all meetings, whether elective or legislative... We count for less than noting in the state. A stupid and profoundly ignorant man counts for more in France than the best educated woman. He can name his legislators; woman cannot. She is a creature apart who is born with many duties and no rights.’ Madeleine Pelletier ‘For a feminist, the extreme care of one’s person and a studied sense of elegance are not always a diversion, a pleasure, but rather often excess work, a duty that she nevertheless must impose upon herself, if only to deprive shortsighted men of the argument that feminism is the enemy of beauty and a feminine aesthetic.’ Margerite Durand, ‘Acting Up,’ French Historical Studies (1996), 1119 ‘In mimicking the real woman, they exposed its artifice as a role that can be staged even in the most unconventional of lives. By mimicking femininity, Durand... [was] able to defang [her] opponents and at the same time reveal the artifice of gender identity.’ Roberts, ‘Acting Up,’ French Historical Studies (1996), 1130 Modern femininity in Femina • Beyond the domestic ideal; showed women performing professional and other roles • Its ‘coverage presumed that women could achieve important advances on their own by raising their sights and exploring their own individuality.’ Lenard Berlanstein, ‘Selling Modern Femininity,’ French Historical Studies, 30:4 (2007), 635 Achievements of French feminism by 1914 • No vote for women but… • Married women allowed to dispose of their own incomes (1908) • Paternity suits allowed (1912) • Raised issue of women’s rights ‘Perhaps the greatest tribute to the force of feminist ideas and activism in fin-de-siècle France was that it precipitated a major public debate and gave rise to a vitriolic antifeminism that forced men (especially those in political power) to take a position on the women question.’ Karen Offen, ‘Depopulation, Nationalism, and Femininsm,’ American Historical Review (1984), 661 French masculinity under threat? • Defeat to Prussia (1870) and the Commune shook the confidence of middle class Frenchmen • French men ‘feared deep down that foreigners saw them as lacking in the honor and warriorlike virility still widely believed to embody masculinity itself.’ E Berenson, Trial of Madame Caillaux, p. 114 The First Empire’s women had been overwhelmed “by the intense and magnificent whirl of activity accomplished by men who returned home between two battles to get them with child, only to hasten back to the front having left behind the overpowering image of conquerors.’ Le Gaulois (1900), quoted in Berenson, Trial of Madame Cailloux (1993), 115 Male honour codes • Hangover from the ancien régime • In private, men must display sexual vigour and potency • In public, they must be ready to defend their reputation and honour, hence the popularity of the duel • See Robert Nye, Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (1993) Sketch by Alfred Grévin (c.1880) ‘Culture of force’ (1890s+) See Christopher Forth, The Dreyfus Affair and the Crisis of French Manhood (2004)