The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

advertisement

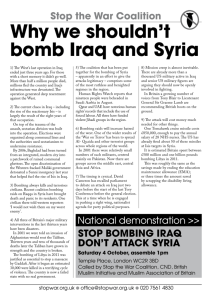

STUDY GUIDE United Nations Security Council The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria 2 GREETINGS ........................................................................................................................... 3 THE UNITED NATIONS ....................................................................................................... 5 UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL ....................................................................... 6 BRIEF LOCAL HISTORY .................................................................................................... 8 THE ISLAMIC STATE IN IRAQ AND SYRIA ................................................................ 11 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 11 GOALS, STRUCTURE AND CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................... 13 ISIS TERRITORIAL CLAIMS ............................................................................................ 14 ENEMIES AND ALLIES.................................................................................................... 15 RELEVANT INTERNATIONAL CONCEPTS ................................................................. 16 SOVEREIGNTY ............................................................................................................... 16 RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT ....................................................................................... 17 ARGUMENTS ON TWO DIFFERENT SIDES ................................................................. 18 THE CASE AGAINST INTERVENTION .............................................................................. 18 RAND PAUL’S FATAL PACIFISM .................................................................................... 21 QUESTIONS A RESOLUTION MUST ANSWER (QARMA) ........................................ 24 3 Greetings Dear delegates, It is an honor to be your director for United Nations Security Council committee of Simulações Anglo 2015. My name is Yago Krügner Figueiredo and I am a former student of Anglo São José, currently attending USP and FGV - majoring, respectively, at Law and Business Administration. My first Model United Nations (MUN) experience was precisely at SiAn, in 2009. As a matter of fact, back then my committee was a United Nations Security Council, regarding the 9/11 attacks. So here we are, six years later, to simulate the same organ with an equally relevant matter: the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Not only our theme is an indispensable subject to be understood in current days, but also the form through which we are going to be able to talk about it enriches the debate at an exponential level. The opportunity to explore different countries’ points of view - while defending one that is not necessarily your own - is very unique. To try to help you, thus, with this effort, Gabriel Zulietti and I have put together this Study Guide. Our expectations are that you read this document with the same passion that we have deployed to write it. We’ve carefully selected references, definitions and arguments in order to facilitate the process of preparation for our debates. However, it is obviously your role to seek for more information regarding our theme to be able to defend whatever is your nation’s point of view with more authority. This Guide only goes to a certain point, in that it exposes the difficulties and explains the current situation of our topic but does not deliver a solution to all the problems it raises. That is, then, you’re responsibility. The delegates are supposed to seek for resolutions that, in accordance with the United Nations’ purposes, deal with ISIS in whichever way they seem fit. Best of luck! Sincerely, Yago Krügner Figueiredo 4 Dear delegates, It is with great pleasure that I present myself as your sub-director of Simulações Anglo 2015. My name is Gabriel Zulietti and I am currently a second year high school student at Anglo São José. This year, in the United Nations Security Council, we will be discussing about an important matter in our society: The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, which is a very significant subject to be studied and understood nowadays. Inside our committee, you, delegates, must strongly discuss and debate with iron fists defending your nation’s point of view in order to get the best resolution in accordance to the United Nations ideals. I hope that this study guide prepared by Yago Figueiredo and I serve you as a base for your researches and preparation for our debates and I hope as well that Simulações Anglo shows to be as marvelous to you as they are to me. Cordially, Gabriel Zulietti. 5 The United Nations The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization established on October 24th, 1945, to promote international cooperation. At its founding, the UN had 51 member states; there are now 193. The UN Headquarters resides in international territory in New York City, with further main offices in Geneva, Nairobi, and Vienna. The organization’s objectives include maintaining international peace and security, promoting human rights, fostering social and economic development, protecting the environment, and providing humanitarian aid in cases of famine, natural disaster, and armed conflict. The UN has six principal organs: the General Assembly (the main deliberative assembly); the Security Council (for deciding certain resolutions for peace and security); the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (for promoting international economic and social co-operation and development); the Secretariat (for providing studies, information, and facilities needed by the UN); the International Court of Justice (the primary judicial organ); and the United Nations Trusteeship Council (inactive since 1994). UN System agencies include the World Bank Group, the World Health Organization, the World Food Program, UNESCO and UNICEF. The UN's most prominent officer is the Secretary-General, an office United Nations headquarters in New York, seen from the East River. held by South Korean Ban Ki-moon since 2007.1 2 1 Section adapted from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations> 2 You will notice, throughout this document, that there are a lot of “Wikipedia” references, which may appear strange to some of you that still have a bad image of the website. This view, however, is outdated and incompatible with current academic developments. Wikipedia has strengthened its content in the past years and it is now a reliable source of information, specially the articles written in English and about big themes such as the United Nations, ISIS and general countries’ information. The delegates are encouraged to use the English Wikipedia as a reference, as long as they also use other sources to legitimate even further their findings and as long as they specify their sources when it is due. 6 United Nations Security Council The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations and it is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of international sanctions, and the authorization of military action through Security Council resolutions: it is the only UN body with the authority to issue binding resolutions to member states. A “binding resolution” is a document approved by one of the United Nations’ subsidiary organs that obligates the parties to follow whatever has been decided. Generally, member states do follow these resolutions, for they know that the results to not following them could be unwanted. Here are four articles of the UN Charter that relate to this issue: Article 25 Article 42 The Members of the United Nations agree to Should the Security Council consider that accept and carry out the decisions of the Security measures provided for in Article 41 would be Council in accordance with the present Charter. inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as Article 41 may be necessary to maintain or restore The Security Council may decide what measures international peace and security. Such action not involving the use of armed force are to be may include demonstrations, blockade, and other employed to give effect to its decisions, and it operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members may call upon the Members of the United of the United Nations. Nations to apply such measures. These may Article 46 include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, Plans for the application of armed force shall be telegraphic, made by the Security Council with the assistance radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic of the Military Staff Committee. relations. Security Council resolutions are typically enforced by UN peacekeepers, military forces voluntarily provided by member states and funded independently of the main UN budget. As of 2013, 116,837 peacekeeping soldiers and other personnel are deployed on 15 missions around the world. Fifteen members compose the Security Council. The great powers that were the victors of World War II - China, France, Russia, the UK, and the US - serve as the body's five permanent members. These permanent members can veto any substantive Security Council 7 resolution, including those on the admission of new member states or candidates for Secretary-General. The Security Council also has 10 non-permanent members, elected on a regional basis to serve two-year terms. The African bloc is represented by three members; the Latin America and the Caribbean, Asian, and Western European and Others blocs by two apiece; and the Eastern European bloc by one.3 In our committee, not all of the actual current states will be represented. While we will keep most of the original members, there will be five alterations: Permanent members Non-permanent members Chad China Egypt Iran France Iraq Jordan Russia New Zealand Spain United Kingdom Syria Turkey United States of America The United Nations Security Council Chamber, in New York. Venezuela 3 Section adapted from: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Security_Council > 8 Brief local history During the Cold War, there was a lot of tension between the United States of America and the Soviet Union. In fact, the entire world saw itself polarized between the capitalist and the socalled communist ideology. One of the most prominent materializations of this dispute was the Soviet War in Afghanistan4, which took place from 1979 to 1989. On one side, Soviet troops aided local Marxist rebels that wanted to implement a socialist government in Afghanistan. On the other, a group called “Mujahedeen” fought for the maintenance of the capitalist society. Wanting to prevent further Soviet expansion, the USA felt it was important to assist the Mujahedeen fighters in order for the local government not to lose control over the valuable lands it held. The CIA then launched a program called Operation Cyclone5, whose official purpose was to assist local Afghani forces against the Soviets. During its most active years, the operation’s costs reached some $630 million dollars – it was one of the most expensive US intelligence operations ever undertaken. However, opposing official US information, analysts claim that Operation Cyclone was vital to strengthen – with money, arms and training – a group known as Maktab alKhidamat (MAK). This group played a central role in the 1989 Soviet withdrawing, as well as the following chaotic events in Afghanistan. Their leader was a man called Osama bin Laden. A few months later, a couple of thousand kilometers to the west, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein declared that his country’s neighbor, Kuwait, was selling petroleum in higher amounts than it was allowed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Saddam proceeded to invade Kuwait, and thus began the First Gulf War. As this was a disproportional measure undertook by the Iraqi government, and as the region held enormous amounts of oil wells; the United Nations Security Council authorized Member States to “use all necessary means” 6 to repel the invasion, which allowed the USA-led military action know as Operation Desert Storm to take place. The western allies held so much more power than Hussein’s army, that only 100 hours after the ground operations began a cease-fire was achieved. 4 < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_War_in_Afghanistan > < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Cyclone > 6 See the full UNSC resolution at: < http://migre.me/oOUwO > 5 9 Operation Desert Storm used heavy air support before engaging in ground operations. Many oil wells were incinerated and a lot of Iraq’s army facilities were engaged by jet fighters, which took base most notably in Saudi Arabia. Following the events of the Gulf War, Saddam Hussein found himself in a very divided country. Sunnis and curds were fighting for the control of the country, and the lack of government power during the civil war allowed terrorist groups to rise. Remarkably, AlQaeda in Iraq (AQI) began its activities in 1999. At this point, however, the main control center of Al-Qaeda was back in Afghanistan, a country that was been controlled by a militia called Taliban (who sheltered and aided bin Laden’s unlawful activities). Pursuing its objectives to fight western influences in the Arab world, the group carried out attacks to the World Trade Center buildings, to the Pentagon and attempted to also do so to the White House, on the 9th of September 2001. As a response to these acts of terror, the United States carried an UN-authorized invasion of Afghanistan, in order to stop the spreading of extremist and deranged visions of Islam – which is, at its core, a peaceful religion. Along with the United Kingdom, US troops took control of Kabul in less than four days and implemented a temporary government that lasted until 2014. In 2003, American president George W. Bush claimed that Saddam Hussein was developing chemical mass-destruction weaponry, and under that pretense he invaded Iraq. This invasion was not allowed by the Security Council and later on UN inspectors proved there were no chemical weapons being developed. Not only do the United States suffer criticism for the Iraq invasion to these days among western countries, but also they have achieved much more hatred among the terrorist groups that were established in Iraq. A few years after the American occupation, AQI started calling themselves “Islamic State of Iraq” (or ISI). 10 A few years down the road, two months before the USA killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, in 2011, the Arab Spring encouraged the Syrian population to rise against Bashar Al-Assad, whose family has been governing the country for decades. Syria is still currently in civil war, and ISI has a great fault in that. The group actively fights Assad’s government and holds very large portions of land in northern Syria. United States Air Force delivers humanitarian aid for Syrian opposition forces. 11 The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria Introduction The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is a jihadist rebel group that controls territory in Iraq and Syria and also operates in eastern Libya, the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, and other areas of the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. The group's Arabic name is transliterated as ad-Dawlah al-Islāmīyah fī al-‘Irāq wash-Shām leading to the Arabic acronym Da‘ish or DAESH. The name is also commonly translated as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria or Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham and abbreviated ISIS. In June 2014, the group renamed itself the Islamic State (IS) but the new name has been widely criticized and condemned, with the UN, various governments, and mainstream Muslim groups refusing to use it. Current ISIS flag. The United Nations has held ISIL responsible for human rights abuses and war crimes, and Amnesty International has reported ethnic cleansing by the group on a "historic scale". The group has been designated as a terrorist organization by the United Nations, the European Union, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Canada, Indonesia, Malaysia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, India, and Russia. Over 60 countries are directly or indirectly waging war against ISIL. The group originated as Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad in 1999, which was renamed Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn - commonly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) when the group pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda in 2004. Following the 2003 invasion of 12 Iraq, AQI took part in the Iraqi insurgency. In 2006, it joined other Sunni insurgent groups to form the Mujahideen Shura Council, which shortly afterwards proclaimed the formation of an Islamic state, naming it the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). The ISI gained a significant presence in Al Anbar, Nineveh, Kirkuk and other areas, but around 2008, its violent methods, including suicide attacks on civilian targets and the widespread killing of prisoners, led to a backlash from Sunni Iraqis and other insurgent groups. The group grew significantly under the leadership of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (picture on the right), and after entering the Syrian Civil War, it established a large presence in Sunni-majority areas of Syria within the governorates of Ar-Raqqah, Idlib, Deir ez-Zor and Aleppo. Having expanded into Syria, the group changed its name in April 2013 to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, when al-Baghdadi announced its merger with the Syrian-based group al-Nusra Front. The group remained closely linked to al-Qaeda until February 2014, when after an eight-month power struggle, al-Qaeda cut all ties with ISIL, citing its failure to consult and "notorious intransigence". On June 29th, 2014, the group proclaimed itself to be a worldwide caliphate under the name "Islamic State", and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was named its "caliph". As caliphate it claims religious, political and military authority over all Muslims worldwide and that "the legality of all emirates, groups, states, and organizations, becomes null by the expansion of the khilāfah's (caliph's) authority and arrival of its troops to their areas". This is while ISIL's actions have been widely criticized around the world, with many Islamic and non-Islamic communities judging the group to be unrepresentative of Islam. ISIL is known for its well-funded web and social media propaganda, which includes Internet videos of the beheadings of soldiers, civilians, journalists, and aid workers. The group gained notoriety after it drove the Iraqi government forces out of key western cities in Iraq while in Syria it conquered and held ground attacks against both the government forces and rebel factions in the Syrian Civil War. It gained those territories after an offensive, initiated in early 2014, which senior U.S. military commanders and members of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs saw as a reemergence of Sunni insurgents and al-Qaeda militants. This territorial loss implied a failure of U.S. foreign policy and almost caused a collapse of the Iraqi government that required renewal of U.S. action in Iraq. 13 Goals, structure and characteristics From at least since 2004, a significant goal of the group has been the foundation of an Islamic state. Specifically, ISIL has sought to establish itself as a Caliphate, an Islamic state led by a group of religious authorities under a supreme leader - the Caliph - who is believed to be the successor to Muhammad. In June 2014, ISIL published a document in which it claimed to have traced the lineage of its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi back to Muhammad, and upon proclaiming a new Caliphate in June, the group appointed al-Baghdadi as its caliph. As Caliph, he demands the allegiance of all devout Muslims worldwide. Regarding ISIS’s financing, many experts claim they are now an auto sufficient organization, which means they have developed ways to get money on their own. This issue is highly important, because it is often suggested that an efficient way to defeat the terrorist group is by cutting their access to resources such as money and weaponry. Brazilian analyst Gustavo Chacra, who writes for O Estado de São Paulo, explains7: “Basically, ISIS controls a huge territory. It is, therefore, more similar to Taliban that to Al-Qaeda. Bin Laden’s net was sheltered by a State (Taliban controlled Afghanistan), while ISIS is the State itself on the areas it controls in Iraq and Syria. I have listed four main ways through which ISIS finances its operations: 1) Extortion – ISIS charges tributes and taxes in the areas that it holds and, in several cases, requires money in order not to kill someone or not to close a store, for example. 2) Theft – when it dominates cities, ISIS takes control of local banks. In Mosul, an Iraqi town, they have acquired tens of millions of dollars in the city’s bank. 3) Contraband – ISIS detains a few oil wells in Iraq and in Syria. Through middlemen, they are able to sell it to other regions of the planet. 4) Kidnapping – ISIS kidnaps citizens from other countries, including people from the Occident, and asks for enormous quantities for the rescue. In mid-2014, Iraqi intelligence obtained information from an ISIS operative which revealed that the organization had assets worth US$ 2 billion, making it the richest jihadist group in the world. About three quarters of this sum is said to be represented by assets seized after the group captured Mosul in June 2014; this includes possibly up to US$ 429 million looted from Mosul's central bank, along with additional millions and a large quantity of gold bullion stolen from a number of other banks in the city. 7 Available at: < http://internacional.estadao.com.br/blogs/gustavo-chacra/quem-financia-o-isisno-iraque-e-na-siria/ > 14 Exporting oil from oilfields captured by ISIL brings in tens of millions of dollars. One US Treasury official has estimated that ISIL earns US$ 1 million a day from the export of oil. Much of the oil is sold illegally in Turkey. Dubai-based energy analysts have put the combined oil revenue from ISIL's Iraqi-Syrian production as high as US$ 3 million per day. Estimates of the size of ISIS's military vary widely from tens of thousands up to 200,000 fighters. ISIS relies mostly on captured weapons. Major sources are Saddam Hussein's Iraqi stockpiles from the 2003 - 2011 Iraq insurgency and weapons from government and opposition forces fighting in the Syrian Civil War and during the post-US withdrawal Iraqi insurgency. The captured weapons, including armor, guns, surface-to-air missiles, and even some aircraft, enabled rapid territorial growth and facilitated the capture of additional equipment. The group also has a long history of using truck and car bombs, suicide bombers, IEDs, and has used chemical weapons in Iraq and Syria. ISIL captured nuclear materials from Mosul University in July 2014, but is unlikely to be able to turn them into weapons. ISIS territorial claims ISIL territorial claims refer to announcements of territorial control and aspirations of control by ISIL. No nation recognizes the organization as a state. As of November 2014, ISIL had claimed provinces in Iraq, Syria, and eastern Libya. ISIL also claims provinces and has active members in Algeria, Egypt, Yemen and Saudi Arabia, but it does not control any defined territory in those countries. The group has attacked and temporarily held territory in Lebanon on a number of occasions, but it is not known to have announced a province there. The red marked regions are under ISIS control; while the white areas refer to regions for which ISIS claims, but doesn’t necessarily exercise control. 15 When the group renamed itself and announced the establishment of the Islamic State of Iraq in 2006, it claimed authority over seven Iraqi provinces: Baghdad, Al Anbar, Diyala, Kirkuk, Salah al-Din, Ninawa, and parts of Babil. In April 2014, the group claimed nine Syrian provinces, covering most of the country and lying largely along existing provincial boundaries: Al Barakah, Al Khayr, Raqqah, Homs, Halab, Idlib, Hamah, Damascus, and Ladhikiyah. A new province was created in August 2014 called al-Furat - "Euphrates" which incorporates territory on both sides of the Syria–Iraq border. On 13 November 2014, al-Baghdadi released an audio-recording in which he stated: "We announce to you the expansion of the Islamic State to new countries, to the countries of the Haramayn [Saudi Arabia], Yemen, Egypt, Libya [and] Algeria". In these countries he announced the creation of five new provinces, each with a governor, while nullifying all local jihadist groups. These areas were singled out because the group had a strong base in them from which it could carry out attacks. However, according to analyst Aaron Zelin from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, only the groups in Sinai and Libya exercise any territorial control and the pledges from Saudi Arabia, Libya and Yemen are anonymous and not from known groups. The Long War Journal writes that the logical implication of alBaghdadi's declaration is that the group will consider Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb illegitimate if they do not nullify themselves and submit to the group's authority. Enemies and allies Every Islamic country in the world is against ISIS, as well as the vast majority of western democracies. Currently, the armies of the following countries are at war against ISIS: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Afghanistan and Yemen. Also, there is a coalition led by NATO8 that carries airstrikes and other forms of nonground attacks. The following countries are involved with this coalition: United States (as the leader), Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and the United Kingdom. As far as supporters go, there are very few agents or organisms that endorse ISIS’s actions. Even Al-Qaeda has considered that the group is too extreme in its actions. Most notably, Boko Haram9 is a terrorist group that endorses DAESH.10 8 See at: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NATO > See at: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boko_Haram > 10 Section on ISIS adapted from:< http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_State_of_Iraq_and_the_Levant > 9 16 Relevant international concepts Sovereignty One of the main concepts to take into account when discussing international legislation for any given subject is sovereignty. The United Nations Charter states, in its second article, that the “organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its members”. But what is sovereignty? For our international studies purposes, we can comprehend two definitions to this concept: I) De jure sovereignty The Latin expression “de jure” means “of law” or “concerning the law”. We can understand it as the legal and institutional definition of sovereignty, and it means “the effective right to exercise control over a territory”. II) De facto sovereignty “De facto”, on the other hand, means “of fact” or “in reality”. It applies to the actual ability of a given State to control its population via legitimate means, and provide them with public services and protection. In international law, sovereignty means that a government possesses full control over affairs within a territorial or geographical area or limit. Determining whether a specific entity is sovereign is not an exact science, but often a matter of diplomatic dispute. There is usually an expectation that both de jure and de facto sovereignty rest in the same organization at the place and time of concern. Foreign governments use varied criteria and political considerations when deciding whether or not to recognize the sovereignty of a state over a territory.11 11 Paragraph from: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sovereignty > 17 Responsibility to protect The Responsibility to Protect (R2P or RtoP) is a proposed norm that sovereignty is not an absolute right, and that states forfeit aspects of their sovereignty when they fail to protect their populations from mass atrocity crimes (namely genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing). The R2P has three "pillars": 1) A state has a responsibility to protect its population from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing. 2) The international community has a responsibility to assist the state to fulfill its primary responsibility. 3) If the state manifestly fails to protect its citizens from the four above mass atrocities and peaceful measures have failed, the international community has the responsibility to intervene through coercive measures such as economic sanctions. Military intervention is considered the last resort. While R2P is a proposed norm and not a law, its proponents maintain that it is based on a respect for the principles that underlie international law, especially the underlying principles of law relating to sovereignty, peace and security, human rights, and armed conflict. R2P provides a framework for using tools that already exist (i.e., mediation, early warning mechanisms, economic sanctions, and chapter VII powers) to prevent mass atrocities. Civil society organizations, states, regional organizations, and international institutions all have a role to play in the R2P process. The authority to employ the last resort and intervene militarily rests solely with United Nations Security Council (UNSC).12 12 Subsection from: < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Responsibility_to_protect > 18 Arguments on two different sides This section will feature two articles with relevant points to our discussions. The first one, written by Adrian Bonenberger, makes a case against an intervention to agains ISIS. The second, by Richard A. Epstein, argues in favor of taking more energetic action. The case against intervention13 On September 10, President Barack Obama delivered a widely anticipated speech addressing the alarming growth in the scope and power of the militant group known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. The president announced that in order to defeat ISIS, the United States would ramp up military intervention in the Middle East, arming insurgent groups in Syria and Iraq and using airstrikes to support allies in the region. The speech was important. For the first time since he announced a surge in Afghanistan at the beginning of his presidency—a surge in which I played a small role, as a company commander deployed to Kunduz Province—the president is publicly and deliberately committing the U.S. military to ongoing actions in that area. Tuesday, he made good on that promise, hitting Islamic State and Al Qaeda targets in Syria and Iraq with airstrikes and cruise missiles. The civil wars in Syria and Iraq have provoked widespread outrage: anger at the unscrupulous and repressive leaders, Assad and al-Maliki, who have governed the countries so ruthlessly; horror at the brutal sectarian violence; grief for the shattered families, the refugees—over 2 million and counting—and the nearly two-hundred-thousand lives lost so far. The natural human response to such suffering is to try to end it as quickly as possible, by any means necessary. In this case, however, acting on that desire is the worst thing America could do. Recent historical evidence suggests that if we intervene, we are less likely to end the suffering than to compound it, stretching the killing out over decades instead of years. Beyond this, the danger is that such a move will play right into the hands of those we wish to defeat. It is important to understand that ISIS does not simply want to kill Americans. True, they don’t like us, and they don’t mind venting their frustration on those citizens unlucky enough to fall into their clutches. But their primary objective is to unify the Middle East under a particularly grim and violent form of Sunni Islam. And the best recruiting tool for ISIS, as for Al Qaeda, has been an America bent on intervention. The limited interventions that we typically undertake today, relying on drone strikes and/or house raids by special forces, all too often set communities against America; such actions may kill one or five or thirty “bad guys”—and create ten or fifty or five hundred more. 13 Article by Adrian Bonenberger, available at: < https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/caseagainst-intervention > 19 This is why ISIS has dedicated so much propaganda toward the West, and why it makes such a gruesome show of beheading Western journalists: ISIS is terrified that America will not get involved. American interventions can make a potential ISIS recruit out of someone whose uncle's house was destroyed by a drone, or help ISIS demagogues blame the United States for the plight of refugees stuck in camps. To someone who has suffered loss or displacement, religious extremism may seem attractive in comparison. When an extremist mullah cuts off the hand of a thief, the act may be barbaric, but it has a measure of logic behind it—unlike, say, a drone strike that wipes out a family celebrating a wedding. Having America as a military enemy helps miscreants like Al Qaeda and ISIS galvanize constituent populations in ways that they cannot if they are seen as merely waging a battle for supremacy with rival believers or ethnic groups. What ISIS relies on is a kind of bait-and-switch. They need us as their enemy. Proponents of a limited intervention against ISIS advocate a combination of counterterrorism plus the military help of a regional proxy. But who should that be? Since neither Iran nor Assad’s Syrian government are acceptable, we are actively considering both the Kurds and the moderate Syrian rebel alliance known as the Free Syrian Army (or FSA). Both options come with severe drawbacks. Arming the Kurds means abandoning the geographical structure of Iraq—a structure that has remained intact since the era of British rule—while enraging and destabilizing our NATO partner Turkey, which has its own Kurdish separatist problem. As for the FSA, they are notoriously unreliable; any weapons or aid we give them tend to end up in the hands of ISIS or the Al Qaeda-affiliated Nusra Front. We cannot simply will a politically convenient partner into existence. In the absence of such a partner we are likely to fall back on the “whack-a-mole” approach of targeting and killing high-ranking terrorists via air strikes or drone strikes, or with Special Operations soldiers such as SEALs, Rangers, Delta, and other deployable (and often deniable) assets. The primary argument against this approach is that we’ve been doing it since September 11, 2001, and the bad guys keep coming. Meanwhile, there's no sign that the ever-popular resort to "surgical" airstrikes will deliver what we want. In his masterful book, The Limits of Air Power: The American Bombing of North Vietnam, Mark Clodfelter argues that bombing does very little to stop people from picking up arms in a conflict. What I observed in two and a half years of combat in Afghanistan convinced me he is right. And what is it that we want, in fact? What rationale lies behind the move to expand our military actions in the region? Some who support greater military intervention in Iraq and Syria cite concern that the United States is about to be attacked by ISIS. But these concerns are wildly inflated; when weighed against, say, the violent deaths caused by the drug war in Mexico, or the potential for thermonuclear war with Russia, the actual threat posed to America by ISIS is trivial. ISIS and Al Qaeda are primarily interested in attacking other 20 groups in their area, with a notable but secondary or tertiary desire to export their violence to America. And intelligence agencies agree; as the New York Times reported recently, no intelligence exists to suggest that ISIS is planning an attack on the United States. As for using the military for humanitarian missions, yes, there are times when intervention makes sense as a last resort, when all other options have been exhausted and we must act to avert catastrophe. Bill Clinton has said that doing nothing during the Rwandan genocide was his greatest regret as president. But such actions require “boots on the ground”—and nobody on the left or right is advocating a full-scale, boots-on-the ground invasion of Iraq or Syria. Air power alone, meanwhile, has rarely stopped a genocide, and the groups we’ve paid over the years to act as our proxies have usually ended up conducting ethnic cleansings of their own. Furthermore, we have not used sanctions to discourage the states, such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia, that are supporting ISIS; indeed we haven't even explored that possibility, at least not publicly. Either stopping genocide isn’t our real objective—whether it should be is a different discussion—or we’re applying the wrong set of tools to the problem. With all the money we have spent—on military invasions, bombs, carrier-group deployments, handouts to corrupt Afghans and Iraqis masquerading as well-intentioned reconstruction efforts—and all the blood we’ve shed, it’s worth reviewing the fruits of our labor. Afghanistan: the Taliban in control of large swaths of countryside, warlords in control of most of the rest. Iraq: an unmitigated disaster, recoverable only by allying with a country led by Holocaust-deniers. Libya: equally grim, thanks to well-armed and dedicated Islamist fighters. Egypt: back under the control of a hated dictator. Yemen: beset by Al Qaeda, Sunni separatists in the east, and Shia separatists in the north and west. Syria: twice as bad as Iraq, if that’s possible. This is what intervention has produced—or at least failed to prevent. There are ways to fight ISIS and Al Qaeda without using bullets or bombs. We can hit them where it really hurts: by reaching the people they cultivate as future fighters. The best way to curb these groups is to address the situation that gave rise to them in the first place— namely, the refugee camps, like those in Pakistan that provided so many Pashtun Sunnis willing to fight against the Soviets, and the secular Afghans that succeeded them. Our best long-term chance for success is to take responsibility for refugee camps, making sure that the 2 million displaced Syrians have a chance at a normal life. Make sure they’re educated, to Western standards. Fed, to Western standards. Brought into the global community. That’s the real fight. There isn’t much we can do about the eighteen-year-old jihadist who's carrying an M4 he picked up off the body of an American-trained FSA militiaman or Iraqi soldier. Our real target is the ten-year-old kid who’s listening to a radical Islamic preacher tell him that the only true way is jihad. 21 Violence begets violence, revenge begets revenge. America has sufficient resources to keep fighting for years, but not indefinitely, and that’s exactly what Osama bin Laden hoped—that we’d exhaust and bankrupt ourselves, fighting in a thousand little conflicts, while providing a recruiting tool for his side's propagandists. Dropping bombs won’t restabilize the region in the short run, while empowering groups like ISIS (or worse) in the long run. With aid, however, we can prevent ISIS from coming back ten times stronger a decade from now. Iran seems fully committed to propping up Iraq and Assad’s regimes. Let’s let them. It’s time we started spending our money on the future, instead of continuing to condemn our present to an irretrievable past. Rand Paul’s fatal pacifism14 For my entire professional life, I have been a limited-government libertarian. The just state should, in my opinion, protect private property, promote voluntary exchange, preserve domestic order, and protect our nation against foreign aggression. Unfortunately, too many modern libertarian thinkers fail to grasp the enormity of that last obligation. In the face of international turmoil, they become cautious and turn inward, confusing limited government with small government. Unwisely, they demand that the United States keep out of foreign entanglements unless and until they pose direct threats to its vital interests—at which point it could be too late. The most vocal champion of this position is Senator Rand Paul. Senator Paul has been against the use of military force for a long time. Over the summer, he wrote an article entitled “America Shouldn’t Choose Sides in Iraq’s Civil War,” for the pages of the Wall Street Journal arguing that ISIS did not threaten vital American interests. Just this past week, he doubled down on this position, again in the Journal, arguing that the past interventions of the United States in the Middle East have abetted the rise of ISIS. His argument for this novel proposition is that the United States should not have sought to degrade Bashar Assad’s regime because that effort only paved the way for the rise of ISIS against whom Assad, bad as he is, is now the major countervailing force. Unfortunately, this causal chain is filled with missing links. The United States could have, and should have, supported the moderate opposition to Assad by providing it with material assistance, and, if necessary, air support, so that it could have been a credible threat against Assad, after the President said Assad had to go over three years ago. The refusal to get involved allowed Assad to tackle the moderates first in the hope that the United States would give him a pass to tackle ISIS, or, better still, even assist him in its demise, as we might well have to do. It is 14 Article by Richard A. Epstein, available at: < http://www.hoover.org/research/rand-pauls-fatalpacifism > 22 irresponsible for Paul to assume that the only alternative to Obama’s dithering is his strategy of pacifism. Paul’s implicit logic rests on a worst-case analysis, under which no intervention is permissible because the least successful intervention may prove worse than the status quo. It is hardly wise to wait until ISIS is strong enough to mount a direct attack on the United States, when its operatives, acting out of safe havens, can commit serious acts of aggression against ourselves and our allies. It is far better to intervene too soon than to wait too long. It is instructive to ask why it is that committed libertarians like Paul make such disastrous judgments on these life and death issues. In part it is because libertarians often have the illusion of certainty in political affairs that is congenial to the logical libertarian mind. This mindset has led to their fundamental misapprehension of the justified use of force in international affairs. The applicable principles did not evolve in a vacuum, but are derived from parallel rules surrounding self-defense for ordinary people living in a state of nature. Libertarian theory has always permitted the use and threat of force, including deadly force if need be, to defend one’s self, one’s property, and one’s friends. To be sure, no one is obligated to engage in humanitarian rescue of third persons, so that the decision to intervene is one that is necessarily governed by a mixture of moral and prudential principles. In addition, the justified use of force also raises hard questions of timing. In principle, even deadly force can be used in anticipation of an attack by others, lest any delayed response prove fatal. In all cases, it is necessary to balance the risks of moving too early or too late. These insights help shape the serious libertarian debates over the use of force. Correctly stated, a theory of limited government means only that state power should be directed exclusively to a few legitimate ends. The wise state husbands its resources to guard against aggression, not to divert its energies by imposing minimum wage laws or agricultural price supports on productive market activities. Quite simply, there are no proper means to pursue these illegitimate ends. In contrast, self-preservation and the protection of others form the noblest of state ends. The late economist and Nobel Laureate James Buchanan always insisted that a limited government had to be strong in the areas where it had to act. Perhaps his views were influenced in his time as an aide to Admiral Chester Nimitz in the Pacific theater during World War II. In responding to aggression, the hard questions are strategic—are the means chosen and the time of their deployment appropriate to the dangers at hand? Move too quickly, and it provokes needless conflict. Move too slowly, and the situation gets out of hand. Senator Paul errs too much on the side of caution. He would clamp down, for example, on the data collection activities of the National Security Agency, which allow for the better deployment of scarce American military resources, even though NSA protocols tightly restrict the use of the collected information. It is wrong to either shut down or sharply restrict an 23 intelligence service that has proved largely free of systematic abuse. The breakdown of world order makes it imperative to deploy our technological advantages to the full. Sensible oversight offers a far better solution. The same is true in spades about the use of force in Iraq and Syria, where matters have deteriorated sharply since Paul’s misguided plea for non-intervention in June. It was foolish for him to insist (and for President Obama to agree) that the United States should not intervene to help Iraqis because the Iraqis have proved dangerously ill-equipped to help themselves. Lame excuses don’t wash in the face of the heinous aggression that the Islamic State has committed against the Yazidis and everyone else in its path. Rand Paul likes to insist that the initial blunder was the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Whether that invasion was right or wrong is irrelevant today. The question now is how to play the hand that we have been dealt. Whatever the wisdom of going into Iraq, peace had been restored by the surge when President Obama took office in 2009. Since then Iraq’s factionalism has grown because Obama signaled disengagement the day he took office, and found himself unable to forge a status of forces agreement in Iraq in 2011. Being eager to get out, he could not figure out a credible way to stay in. Unfortunately, Rand Paul writes as if Iraq’s many deficits are fixed facts of nature, wholly independent of the flawed U.S. policies that he has consistently backed, in sync with Obama’s aloof detachment. Yet these policies, tantamount to partial unilateral disarmament, have given our worst enemies the priceless assurance that they can operate largely free of American influence and power. There is nothing in libertarian theory that justifies dithering at home as conditions abroad get worse by the day. A nation that believes in the primacy of liberty has to defend it at home and abroad, and do so over the long haul, without imposing artificial deadlines on its military commitments. Our enemies place no such limits on their efforts to kill and uproot innocent people. Our limited airstrikes have shown that force can make a positive difference. Only a fresh willingness to confess error about the President’s decision to remove ground troops from Iraq and keep all American forces out of Syria can reverse the present downhill trend. Containment is wishful thinking, not a stable option. Sadly, where the Islamic State goes, there we must ferret them out. The American people may be weary of war. But they will become wearier still from the chaos that will follow if we neglect to fight the forces of death and destruction. Senator Paul’s position is inexcusable. It renders him unfit to serve as President of the United States should he be eyeing the 2016 candidacy. Our commander-in-chief cannot be a bystander in world affairs. He has to have the courage to lead and rally a nation in times of trouble, lest the liberties that we all cherish perish by government indifference and inaction. 24 Questions a Resolution Must Answer (QARMA) Are the countries occupied by ISIS capable of fighting the group by themselves? Should these countries’ sovereignties be outlawed? Should ISIS be fought by an international coalition? Should the Security Council allow the usage of force? What other means should be deployed to fight ISIS? Are there any non-violent options? Should there be sanctions to other organizations and/or countries found to be helping ISIS in any way? Is some sort of reparations to the civilian victims in order? If so, where should these reparations aids come from? Are there any humanitarian actions that can take place?