Powerpoint

advertisement

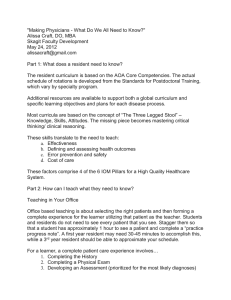

Santa Monica Community College May 6, 2011 Lia D. Kamhi-Stein (lkamhis@calstatela.edu) Professor, MA in TESOL Program California State University, Los Angeles 1. 2. 3. Describe the profiles of international students, late-arriving and early-arriving resident students; describe three students that reflect the experiences of the three groups; identify a variety of academic literacy strategies (focusing on reading) designed to help the three groups improve their content knowledge and reading skills. Students Definitions International Students • Born and raised outside the U.S.; • studied English in EFL settings; • come to the U.S. on a foreign student visa for purpose of studying • return to their country once they have completed their studies. Resident Students (I): Late-Arriving Students • Arrived in the U.S. after the critical period; • may or may not have studied English before their U.S. arrival; • plan to live in the U.S. Resident Students (II): Early-Arriving Students (Caveat: Can a U.S.-born person be called a “resident” student?) • Born or arrived in the U.S. before the critical period; • may or may not have studied English before their U.S. arrival; • Have immigrant parents Characteristic International Students Late-Arriving Resident Students Early-Arriving Resident Students Socioeconomic Status Upper-middle class & higher Working class & higher Working class & higher Purpose for Studying English Instrumental Survival & integrative Like monolingual students Roles of the two languages Diglossic situation (one language used at home, English used outside the home) Knowledge of culture Home country Strong Strong Wide range U.S. Limited Limited Strong L1 Highly literate Varying degrees Limited L2 Limited Wide range; in most cases, none to limited Extensive, though inconsistent Literacy Experience Characteristic International Students Late-Arriving Resident Students Early-Arriving Resident Students Initially C1 (“we” vs. “they”). Eventually, they develop the ability to fit into both cultures (unless they choose not to do so) May question and/or are questioned about their cultural identity (what am I?; Why am I placed in ESL classes?) Often associate with similar students and/or speakers of non-standard dialects Cultural Identity C1 Home culture C2 Do not identify with the U.S. Perceptions Self Positive (though the change in setting--EFL to Inner Circle--may affect selfperceptions ) Wide range : low to high, depending on how they view their home culture (problem or asset) Wide range : often dependent on how they view their C1 (problem or asset) Often feel that their teachers do not understand them Oth ers Positive (though accentedness and intelligibility may be perceived as May depend on many factors; they may experience discrimination May depend on many factors (ethnic group to which they belong, visible minority, Students Classroom Experiences Orientation to ELD Implications for Academic Instruction in English International Students Had positive experiences Eye learner (formal study—learning) Resident Students (I): Late-Arriving Students Exposed to inconsistent instruction and expectations. Eye learner (though it may depend on age of arrival) Grammar: Explicit knowledge Listening and speaking: weak Vocabulary: mostly limited to TOEFL Reading: Strong foundation, range in practice Academic classroom: Challenged w/pace, turn-taking, degree of informality, cultural beliefs about teachers’ & students’ roles, selfperceptions about pronunciation Resident Students (II): Early-Arriving Students Exposed to inconsistent instruction and expectations. Ear learner (informal, naturalistic acquisition) Grammar: Intuitive, like monolinguals Listening and speaking: appear fluent and confident Reading: weak Vocabulary: highly colloquial, limited academic vocabulary (typical of all students) Academic classroom: Understand expectations; sometimes, they may Originally from Turkey; high middle class Began EFL studies in high school, at the age of 15; came to the U.S. to study at SMC, transferred to UCLA Was an eye learner; Had strong self-perceptions that were challenged by peers Strengths: Had strong literacy skills in Turkish Had explicit knowledge of English grammar and metalinguistic awareness Was a strategic learner Challenges: Had limited background knowledge (about content and culture) to complete reading assignments Experienced a high cognitive reading load; had trouble keeping up with the readings and the amount of vocabulary to learn (more details later) Had not done much writing in English (academic or other) in Turkey Used or knew only one register: “book” English Had limited understanding of the culture of the U.S. classroom Originally from Mexico; working class Arrived in the U.S. at the age of 11, did not know any English Was a model student in Mexico and below grade level in the U.S. Was not accepted by peers in her own ethnic group ; was frustrated by the pronunciation of words in English, her peers laughed at her Hated the “ESL label,” wanted to be a “regular student;” decided to enroll in the “ESL track” ESL classes did not integrate language and content, she did not feel challenged since all she did was worksheets Transferred to mainstream classes as a senior; was challenged and supported by her English teacher Graduated from high school with honors, but “did not know how to read, write or speak “proper” English; she memorized but did not understand materials Did not give up, attributes her success in learning how to read to a commercial reading program Enrolled in a community college, where she took courses for 4 years, until she transferred to the CSU system. Born in Southern California in a Mexican, working class family Spoke Spanish at home; English at school Was an ear learner Interacted with Mexican American students Felt his teachers did not care about teaching him or his peers; he perceived them as having low expectations (Why am I going to teach you if you are not going to go to college?) Was admitted to CSU school, where he completed a BA in French Found himself to be lost in academia (voiceless in the classroom) Struggled with academic register: wrote as he spoke Was a fluent reader, but was not used to reading academic texts Was determined to succeed 1. Limited academic vocabulary 2. Reading fatigue 3. Reading rate 4. Lack of concentration 1. May read in a linear manner (from beginning to end, without paying attention to helpful features of the text). 2. May mentally translate into the home language to construct meaning (found for readers proficient in their L1 who viewed the L1 as a resource). 3. May focus on individual words to help construct meaning (readers with interrupted or extended K-12 U.S. schooling). 4. May engage in dictionary-based word-hunts (excessive & poor use of dictionaries, readers with interrupted or extended K-12 U.S. schooling). 5. May engage in limited interaction with the text. 6. May not have enough culture or rhetorical knowledge 7. May read slowly, get tired, and give up 8. May not have enough knowledge of English to transfer skills and strategies 1. Help students develop reading confidence and improve their concentration: a. Extensive reading (focusing on teacher- and student-selected resources) b. Timed reading (students read at a comfortable pace) and paced reading (the teacher imposes the rate for reading—increased every week by 25 WPM) Timed Reading Step 1: Preview: A. Read the title. B. Read the first sentence. C. Read the last sentence. D. Scan the article (names, dates, numbers, facts, etc.) Step 2: Read for meaning: Build concentration. B. Reading in chunks, thought groups. C. Question the writer. Step 3: Grasp paragraph sense. A. Find the topic sentence. B. Understand the paragraph structure. Step 4: Organize facts. A. Discover the author’s plan. B. Relate as you read. Students complete multiple choice questions and record results on a reading chart Spargo, E. (1998). Timed reading plus: 25 two-part lessons with questions for guiding reading speed and comprehension (book one). Lincolnwood, IL: Glencoe Mc Graw-Hill. 2. Teach vocabulary: a. Be selective about the words you target. Consider word frequency, salience, students’ goals, the word’s learning burden (Zimmerman, 2009) b. Focus on the Academic Word List (AWL) (Coxhead, 2000) (See attached handout) http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/~alzsh3/acvocab/wordlist s.htm c. Have students think strategically about the vocabulary [vocabulary cards, rating vocabulary knowledge (Coxhead, 2000), collocations, word parts, vocabulary use, etc.] Zimmerman, C. B. (2009). Word knowledge: A vocabulary teacher's handbook. New York: Oxford University Press. Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word List. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213-38. Pritchard, R. (2004). Strategic reading for English learners: Principles and practices. CATESOL Journal, 16(1), 29-42. 3. Use tools like The compleat lexical tutor, http://www.lextutor.ca/ , to analyze the vocabulary in a text that you want to use text. Go to Vocabulary Profiler and click on Classic View to analyze the 3. Integrate instruction in the most common reading-to-write skill students will need to survive in academia: summarization Two approaches: a) cognitive b) text-structure Engage students in activities that go from knowledgetelling (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987) to knowledge transforming (writing a critique) 4. Dobson & Feak’s (2001) cognitive modeling approach: 1. Understanding and discussion: Students read on a single topic (including competing rejected ideas); form simple opinions on the topic. 2. Evaluation: Students are given a set of questions that model the cognitive operations that are used to evaluate a text. Who is the audience? What is the issue? What are the author’s conclusions? What evidence is presented and how good is the evidence? How good is the study, if one is presented? Is the author’s position based on the evidence? What assumptions does the author make? 3. Constructing the Critique: Students write a critique that is not based on personal opinion. Regardless of the content or skills we teach, students benefit from instruction that: 1. is systematic; 2. recycles vocabulary, tasks and materials in different contexts; 3. engages students in discovery or awareness activities, and activities that allow them to practice and extend their knowledge; and 4. provides them with models and opportunities for analysis (in terms of discourse features, language, audience expectations, text structure, genres, etc.)