View/Open - Sacramento

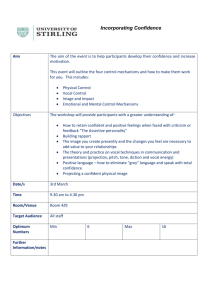

advertisement