Marcellin_Socratic Seminar

advertisement

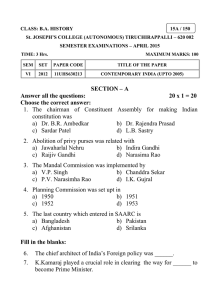

Marcellin_Socratic Seminar Quit India: Ghandi’s Call for Non-Violent Protest Grade: 10 Subject: World History II Length: 90 minutes Context and Overview: This seminar will further develop students’ understandings of the movement for Indian Independence. British imperial rule over India began in the late nineteenth century and extended into the second half of the twentieth century. Through the British East India Trading Company, as well as governmental authority in the British Raj and a caste system, Britain maintained allencompassing control of the Indian people. Protests spanned across the entire period of British rule, and Indian leaders had different ideas regarding which strategies the Indian people should use to gain their independence. The Indian National Congress (INC) represented a portion of the movement which, though developed through militant tactics, took a moderate approach. They called for basic rights of representative government for the Indian people, and extended economic rights. As the movement continued to develop through the 1920s, Mohandas Gandhi became a central leader of the Indian Independence Movement. Gandhi called for nonviolence and civil disobedience, as opposed to the militant tactics used by the Indian National Army (INA). Gandhi defined nonviolence and civil disobedience as “a civil breach of unmoral statutory enactments…” in which the people must cease to respect and cooperate with corrupt governments. This strategy was steadfastly implemented by Gandhi’s supporters across India, culminating in the Quit India Movement. Nonviolent civil disobedience succeeded, and India gained its independence 1947. This opened the door for India to develop as a democratic nation, though there were still many economic and cultural barriers to India’s development. In a socratic seminar, students read a common text and engage in teacher-guided discussion of the text. Students may read the text before class time, or at the beginning of class. Students must actively participate in the discussion in order to reveal and comprehend the many elements of the text. Thus, it is required that students complete a “seminar ticket” prior to entering the discussion. This “seminar ticket” consists of basic questions which assess whether the student has completed the reading, and lay a foundation for the guiding questions of the discussion. A socratic seminar is an appropriate format for this lesson, because it gives students the opportunity to develop “firsthand experience” with a popular movement. Popular movements are elements in history that are inherently based in social experience. By reading a speech given in support of the movement, and discussing students perceptions and judgments of both the speech and the overall movement, students will be able to develop a better understanding of Gandhi and the Indian Independence Movement. Marcellin_Socratic Seminar Objectives: The objectives for this lesson are based on the World History II SOL 14.a: The student will demonstrate knowledge of political, economic, social, and cultural aspects of independence movements and development efforts by describing the struggles for self-rule, including Gandhi’s leadership in India and the development of India’s democracy. Students will be able to identify and describe Mohandas Gandhi and his significance. Students will be able to discuss the elements of nonviolent civil disobedience in the Indian Independence Movement. Students will be able to identify, analyze, and interpret primary and secondary sources to make generalizations about events and life in world history. (WHII.1a) Assessment: Students will turn in both an entrance and exit seminar ticket. Students will also be assessed on active participation through teacher observation and documentation. Procedures: 1. Prior to class: a. Students should read Gandhi’s “Quit India Speech,” and complete the seminar entrance ticket. b. Instructor should set up desks in either a horseshoe (with opening facing front), or in inward facing rows. 2. Warm-Up (5-7 minutes): a. Identify present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka; answer review questions about British imperialism and Indira Gandhi. b. During the warm-up, the instructor should collect the seminar entrance ticket. 3. Instructor guided notes on Indian Independence: Part I (20 minutes). a. This section of notes should cover a short review of India under British rule, the development of the Indian National Congress, and an introduction to Mohandas Gandhi and nonviolent civil disobedience. 4. Class-wide discussion a. First, the instructor should remind the students of the “rules of the road” for discussions. i. Treat others with respect; listen. ii. No raising hands. iii. Use names. iv. Use evidence from the reading to support or question ideas. Question ideas, not people. Marcellin_Socratic Seminar b. Students should take out their copy of the speech. If any students forgot or lost their copy, the instructor should provide them with one. Before beginning discussion, the instructor should review challenging vocabulary with the class (i.e. . c. Discussion will move through a series of questions, as prompted by the instructor. Students should be given ample time and independence to explore each question; there is no “right” or “wrong” answer for each question, and students should attempt to extend their answers through connections to other parts of the text or other questions their answers may pose. d. Discussion questions: i. Opening Question: 1. What is the message of this speech? ii. Core Questions: 1. Do you agree or disagree with Gandhi’s goals? 2. Do you support or question the strategy of nonviolence? 3. Do you think civil disobedience can be successful? 4. Why should the Indian people “free themselves of hatred” towards the British? iii. Potential Follow Up Questions: 1. Prompt students to answer the “why or why not” for each question 2. Prompt students to explain how their answer is supported by the text, or if they are summarizing text to find a specific quote. e. Discussion wrap up and exit ticket: i. Students should write a short paragraph (3-4 sentences) summarizing the discussion, including: whether they agree or disagree with Gandhi’s goals, whether they support nonviolence or not, and whether or not they think civil disobedience can be successful. The instructor should encourage the students to incorporate a quote from the text, what their peers said during the discussion, and generally what they will take away from the discussion. 5. Complete instructor guided notes on Indian Independence: Part II (10 mintues). a. This section of notes should cover the success of nonviolent civil disobedience, the Indian Independence Act of 1947, and the development of Indian democracy (including westernization under Jawaharlal Nehru, the 1950 Constitution, and the division of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka). Differentiation and Adaptations: This lesson hits on many different activities and modes for student learning and expression. There is traditional lecture and note taking, for students who learn best from listening and writing. Both written and verbal assignments allow students to demonstrate their Marcellin_Socratic Seminar understanding in different ways. This lesson could be further differentiated for a creative product by asking students to write a letter to Gandhi, either supporting or arguing against the “Quit India” Movement, as an exit ticket or homework. The text for this seminar is fairly short, and the students have the opportunity to read it at home. It does present some challenging vocabulary. For honors or AP students, I might include finding the definitions as part of their entrance ticket; whereas, for standard and inclusion students, I would include a list of challenging vocabulary and their definitions. If I have students who struggle specifically with a reading disability, I would coordinate with them, the special education co-teacher, and/or the reading specialist to set aside a time where they can read the text with instructor guidance. For students who have hearing impairments, I would look into obtaining microphones so that the student can more fully participate. I might also make a transcript of the seminar which the student can review later. The student will have the opportunity to share their thoughts with the instructor at least, through the exit ticket. Reflection: This lesson may be challenging for students who have never participated in a large scale discussion. Teacher-guidance and prompting questions can be very helpful in keeping participation up. The instructor might also provide a way for students to keep track of the number of times they have participated—this allows shy students to see their participation in the discussion as less intimidating, and chatty students to manage their participation. By sandwiching the discussion between note-taking activities, the instructor can ensure that students get all of the necessary SOL content, and that there is some consensus on the answers to the core discussion questions. Resources: Indian Independence Part I and II Powerpoints Mohandas Gandhi; “Quit India” Speech Questions on Gandhi’s “Quit India” Speech Marcellin_Socratic Seminar Name: _______________________________________________________________ Block:_________ Mohandas Gandhi’s “Quit India” Speech Before you discuss the resolution, let me place before you one or two things, I want you to understand two things very clearly and to consider them from the same point of view from which I am placing them before you. I ask you to consider it from my point of view, because if you approve of it, you will be enjoined to carry out all I say. It will be a great responsibility. There are people who ask me whether I am the same man that I was in 1920, or whether there has been any change in me. You are right in asking that question. Let me, however, hasten to assure that I am the same Gandhi as I was in 1920. I have not changed in any fundamental respect. I attach the same importance to non-violence that I did then. If at all, my emphasis on it has grown stronger. There is no real contradiction between the present resolution and my previous writings and utterances. Occasions like the present do not occur in everybody’s and but rarely in anybody’s life. I want you to know and feel that there is nothing but purest Ahimsa1 in all that I am saying and doing today. The draft resolution of the Working Committee is based on Ahimsa, the contemplated struggle similarly has its roots in Ahimsa. If, therefore, there is any among you who has lost faith in Ahimsa or is wearied of it, let him not vote for this resolution. Let me explain my position clearly. God has vouchsafed to me a priceless gift in the weapon of Ahimsa. I and my Ahimsa are on our trail today. If in the present crisis, when the earth is being scorched by the flames of Himsa2 and crying for deliverance, I failed to make use of the God given talent, God will not forgive me and I shall be judged unjustly of the great gift. I must act now. I may not hesitate and merely look on, when Russia and China are threatened. Ours is not a drive for power, but purely a non-violent fight for India’s independence. In a violent struggle, a successful general has been often known to effect a military coup and to set up a dictatorship. But under the Congress scheme of things, essentially non-violent as it is, there can be no room for dictatorship. A non-violent soldier of freedom will covet nothing for himself, he fights only for the freedom of his country. The Congress is unconcerned as to who will rule, when freedom is attained. The power, when it comes, will belong to the people of India, and it will be for them to decide to whom it placed in the entrusted. May be that the reins will be placed in the hands of the Parsis, for instance-as I would love to see happen-or they may be handed to some others whose names are not heard in the Congress today. It will not be for you then to object saying, “This community is microscopic. That party did not play its due part in the freedom’s struggle; why should it have all the power?” Ever since its inception the Congress has kept itself meticulously free of the communal taint. It has thought always in terms of the whole nation and has acted accordingly. . . I know how imperfect our Ahimsa is and how far away we are still from the ideal, but in Ahimsa there is no final failure or defeat. I have faith, therefore, that if, in spite of our shortcomings, the big thing does happen, it will be because God wanted to help us by crowning with success our silent, unremitting Sadhana1 for the last twenty-two years. I believe that in the history of the world, there has not been a more genuinely democratic struggle for freedom than ours. I read Carlyle’s French Resolution while I was in prison, and Pandit Jawaharlal has told me something about the Russian revolution. But it is my conviction that inasmuch as these struggles Marcellin_Socratic Seminar were fought with the weapon of violence they failed to realize the democratic ideal. In the democracy which I have envisaged, a democracy established by non-violence, there will be equal freedom for all. Everybody will be his own master. It is to join a struggle for such democracy that I invite you today. Once you realize this you will forget the differences between the Hindus and Muslims, and think of yourselves as Indians only, engaged in the common struggle for independence. Then, there is the question of your attitude towards the British. I have noticed that there is hatred towards the British among the people. The people say they are disgusted with their behavior. The people make no distinction between British imperialism and the British people. To them, the two are one This hatred would even make them welcome the Japanese. It is most dangerous. It means that they will exchange one slavery for another. We must get rid of this feeling. Our quarrel is not with the British people, we fight their imperialism. The proposal for the withdrawal of British power did not come out of anger. It came to enable India to play its due part at the present critical juncture It is not a happy position for a big country like India to be merely helping with money and material obtained willy-nilly from her while the United Nations are conducting the war. We cannot evoke the true spirit of sacrifice and velour, so long as we are not free. I know the British Government will not be able to withhold freedom from us, when we have made enough self-sacrifice. We must, therefore, purge ourselves of hatred. Speaking for myself, I can say that I have never felt any hatred. As a matter of fact, I feel myself to be a greater friend of the British now than ever before. One reason is that they are today in distress. My very friendship, therefore, demands that I should try to save them from their mistakes. As I view the situation, they are on the brink of an abyss. It, therefore, becomes my duty to warn them of their danger even though it may, for the time being, anger them to the point of cutting off the friendly hand that is stretched out to help them. People may laugh, nevertheless that is my claim. At a time when I may have to launch the biggest struggle of my life, I may not harbor hatred against anybody. Marcellin_Socratic Seminar Name: _______________________________________________________________ Block:_________ Questions on Gandhi’s “Quit India” Speech 1. Has Gandhi changed since 1920? 2. What does Gandhi support in all of his “writings and utterances”? 3. What is Ahimsa? 4. Who will power belong to, and what will they do with it? 5. According to Gandhi, what did the French and Russian Revolutions fail to do? Why? 6. Does Gandhi believe Indian people should hate British people?