Witness and narrator: Addressing problems

of secondary traumatic stress and

compassion fatigue in spoken language

interpreting

Dr. Emily Becher and Chris Mehus, MA, doctoral candidate

Who we are

• Couple and Family Therapists

• Work a lot with trauma

• We have each worked with interpreters

through our research

How we got here

• We observed a lot of variety within the

interpreters we have worked with

• We highly value and are grateful for

interpreters and the work you do

• We are still outsiders and still learning

Overview

• Defining secondary traumatic stress

• Research in this area

• What to do about it

– Prevention

– Intervention

Terminology

• Secondary traumatic stress

• Burnout

• Compassion satisfaction

Secondary traumatic stress

• Sometimes called compassion fatigue

• A little different than vicarious trauma

• Refers to the presence of symptoms

similar to PTSD resulting from indirect

exposure to traumatic material

Burnout

• Exhaustion

• Less satisfaction

• Can be unrelated to secondary

traumatic stress

Compassion Satisfaction

• Positive feelings related to work

• Feeling good about the difference you

make through your work

• Can protect against burnout

Secondary Traumatic Stress

•

•

•

•

•

Hypervigilance

Avoidance/ coping

Intrusive thoughts

Anger or irritability

Loss of empathy

•

•

•

•

Fearful or jumpy

Exhaustion

Social withdrawal

Emotionally down

or feeling numb

Secondary Traumatic Stress

• Symptoms might impact personal life

and/or professional life

Secondary Traumatic Stress

•

•

•

•

•

Hypervigilance

Avoidance/ coping

Intrusive thoughts

Anger or irritability

Loss of empathy

•

•

•

•

Fearful or jumpy

Exhaustion

Social withdrawal

Emotionally down

or feeling numb

Our brains protect us!

• This is all a result of our brains doing

what they are supposed to do

• Our brain learns to look out for things

that hurt us and then try to avoid them

Really abbreviated brain info

• Primitive brain: emotion and immediate

reaction (fight, flight, or freeze)

• Cognitive brain: logic and reasoning

Memories

•

•

•

•

Sensory information

Thoughts

Physiological changes

Emotions

Example

Think of a positive memory

Sensory

Thoughts

Sweet Smell

Sound of

Mixing

Emotions

Warmth from

Oven

Slow

Breath

Happy

I love

Sweets

Content

Singing

Physical

I’m

safe

Calm

Slow

HR

Muscles

Relax

Sensory

Thoughts

Sight of ___

Crying

Emotions

Smell of ___

Heart

racing

Scared

I’m

going to

die

Helpless

Loud noise

Physical

Police

aren’t

safe

Rage

Sweaty

palms

Muscles

Tense

Old and new memories

• Past experiences (or memory webs)

can get brought up

• New associations (or memory webs) are

created

Our brains protect us

• Making this connections is protective

• Symptoms of secondary traumatic

sense make more sense now

Secondary Traumatic Stress

•

•

•

•

•

Hypervigilance

Avoidance/ coping

Intrusive thoughts

Anger or irritability

Loss of empathy

•

•

•

•

Fearful or jumpy

Exhaustion

Social withdrawal

Emotionally down

or feeling numb

A metaphor

• Books in a cabinet

Research

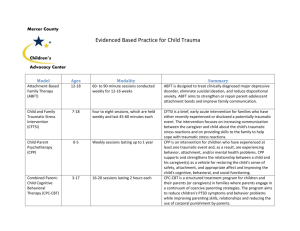

Research: Background

• Increasing attention since 1995

• Recognition that professionals may face

direct and indirect exposure, as well as

having a personal trauma history

Research: Prevalence

• Some researchers have found similar

rates of secondary traumatic stress

across disciplines

• Although some may be at higher risk

(e.g., as many as 50% of child welfare

workers vs. 5-25% of trauma therapists)

Research: Risk Factors

• Personal history of psychological

trauma

• High levels of empathy

• Sharing a similar background with the

client

Research: Risk Factors

• Work environment and stress

– High demand and low control

– Workload

– Lack of support

• Working primarily with trauma-related

cases

Research: Risk Factors

• Possibly gender

• Interpreters convey traumatic content in

first person

• Interpreters are more likely to be from

the same community as the client

Protective Factors

• Supportive work environments

• Good self-care

• Debriefing or consultation

This will be covered more later today

Our Research

• Online survey with a measure of

secondary traumatic stress, compassion

satisfaction, and burnout

• Also asked open ended questions

• Interpreters across Minnesota

Our Research

• Before we share our results, what do

you expect?

– Levels of STS, CS, and burnout?

– What do you think people said in terms of

stress related to interpreting?

– Do you think your experience is similar to

the experiences of other interpreters?

Our Study: Participants

•

•

•

•

N = 119

81 women, 36 men

24 reported refugee or asylee status

Age:

Our Study: Participants

• 30 languages represented in total,

most common:

– Spanish (25%)

– French (6%)

– Somali (6%)

– Hmong (5%)

Our Study: Participants

• Most commonly-reported highest level

of training was 40-hour training for

medical interpreters (41%), followed by

18% completing certificate or degree

Our Study: Participants

• Country of origin:

• Fields interpreted in:

United States

41

Mental Health

94

Mexico

13

Medical

109

Laos

8

Legal/Court

43

Somalia

7

Human Services

85

29 other countries

50

Other Gov.

47

Our Study: Findings

* CS: t = 9.94, d = .77

* ST: t = 4.48, d = 1.25

p < .017

Our Study: Findings

Our Study: Findings

• “Average” interpreter: high compassion

satisfaction and high secondary

traumatic stress with similar rates of

burnout to other helping professionals

• Some comments from participants who

reported high CS and high STS:

Our Study: Summary

• Compared to other helping professions, our

sample reported high STS, high CS, and

normal levels of burnout

• Some reported feeling supported and valued,

while other reported feeling disrespected,

exhausted, and in need of support

So what to do about it?

What to do - Prevention

• Psycho-education

– Signs and symptoms

• Professional Development & skills training

– Feeling competent and understanding your role

• Supervision and support

– Debriefing

Psycho-education

• Understand what STS is, the symptoms,

and what you are most likely to see

change in yourself

• Know you are not crazy

Secondary Traumatic Stress

•

•

•

•

•

Hypervigilance

Avoidance/ coping

Intrusive thoughts

Anger or irritability

Loss of empathy

•

•

•

•

Fearful or jumpy

Exhaustion

Social withdrawal

Emotionally down

or feeling numb

Psycho-education

• Really, you are not crazy

• Our brains try to protect us

• Teach your family about the possible

impact of your work and about STS

Professional Development

• Competence is protective

– Decreases stress

– Increases likelihood of compassion

satisfaction

• Know the bounds of your role

Professional Development

• Remember that you are integral to

patient care and a valuable member of

the human services community

• Create and validate this narrative

Supervision and Support

• Important to have people who can listen

and support you

• Who are those people for you?

• Confidentiality and debriefing

Example

You recently worked with a family and a

caseworker about reported child abuse. You

know of this family because they are part of

your community but you don’t personally know

them. Something about the child reminded you

of something from your past. You get through

the meeting but after it is over you feel

exhausted, numb, and detached from the world.

Example

• Talk with a few people about what

would be appropriate to share or not

share with a supervisor. How about with

a family member?

Example

You recently worked with a family and a

caseworker about reported child abuse. You

know of this family because they are part of

your community but you don’t personally know

them. Something about the child reminded you

of something from your past. You get through

the meeting but after it is over you feel

exhausted, numb, and detached from the world.

Practicing prevention

• Role-play debriefing with a peer while

maintaining confidentiality

Supervision and Support

• Helpful to have people who understand

your situation

– Validation that you aren’t crazy

– Prevents isolation

– Reminds you that your work is valuable

Workplace best practices

Nurses: Offer on-site counseling, support

groups for staff, de-briefing sessions, art

therapy, massage sessions, bereavement

interventions, and attention to spiritual

needs (Boyle, 2011)

Workplace best practices

Social workers:

• Organizational culture and values

• What does it mean to be a supportive organization?

Vacations, diverse case-load, opportunities for prof.

development, emphasis on self-care

• Environment is safe, comfortable and private

Workplace best practices

Social workers continued:

• Trauma specific-education

• Group support, social support within the organization,

spectrum of less formal to more formal structured debriefing, peer support groups

• Supervision and resources (Bell, Kulkarmi, & Dalton,

2013).

Workplace best practices

• Students:

• Same as previously discussed

• Addition of Empowerment

• Feeling in control, working towards

political/social change, feeling like you are

apart of proactive problem solving (Zurbriggen,

2011)

What does interpreter

empowerment look like?

Quick poll: How many people in the audience

have been in professional interpreting

situations and have observed unethical

professional behavior or behaviors that you

just felt were “not right”? Please raise your

hand.

What does interpreter

empowerment look like?

• Quick poll: Now, in those experiences, how

many of you felt that you knew who to report

that unethical or uncomfortable behavior to?

Or felt that reporting that behavior would

actually lead to a positive outcome? Please

raise your hand.

The empowered professional

• In the field of MFT

http://mn.gov/health-licensing-boards/marriage-and-family/public/complaints.jsp

Lawyers

Police officers: Must file a formal

complaint to the local agency that

employs the officer

For example:

http://www.ci.minneapolis.mn.us/police/

opcr-complaint

Personal best practices

• Self-care

• Stress-management

Small group discussion

Question 1: Are there strategies that your

organization could implement, or that

you could implement within your

organization that would decrease the

likelihood of secondary traumatic stress

and burnout for interpreters?

Small group discussion

• Question 2: What self-care or stress

management practices do you engage

in that help you cope with a difficult

interpreting session?

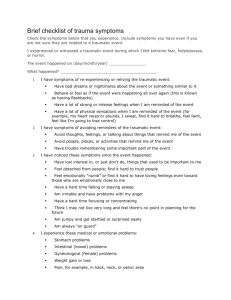

How do I know if there’s a

problem?

STS symptom list:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Feeling emotionally numb

Heart pounding when thinking about work with patients

Feeling like you’re reliving the trauma of your patients/clients

Trouble sleeping

Feeling discouraged about the future

Reminders of work upset you

Little interest in being around others

Feeling jumpy

Being less active than usual

How do I know if there’s a

problem?

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Thinking about work with patients/clients when you didn’t intend to

Trouble concentrating

Avoiding people, places or things that remind you of work with patients

Disturbing dreams about work with patients

Wanting to avoid working with some patients

Easily annoyed

Expecting something bad to happen

Noticing gaps in memory about patient sessions (Bride et al., 2004)

Who should I go to?

•

•

•

•

•

•

Trusted mentor and peers

Medical doctor

Mental health professional

Spiritual advisor

Trusted supervisor

Family

What options are available to

get help?

• Depends on your level and duration of symptoms

• Low levels may be helped by decreasing/diversifying

work-load, sharing experiences with trusted person,

increasing stress management/ self-care

• Prolonged moderate to high levels may need

professional help

– Working 1 on 1 with a therapist

– Joining a psycho-education, support group

Can I still work if I’m

experiencing symptoms?

•

•

•

•

Typically a spectrum

Low level: Distress

Moderate level: Impairment

High level: Improper behavior

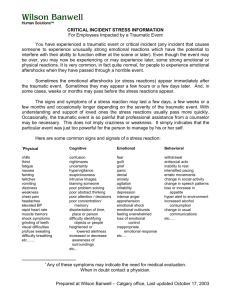

Definitions

• Distress “unresolved intense stress”,

“distracting”, “difficult to manage”.

• Impairment: “functionality of the

professional is compromised”.

• Improper behavior: dual relationships,

etc. (APA Advisory Committee on Colleague Assistance,2015)

Improper behavior and STS

Question: When you think of colleagues you

have known, can you identify a time when

you observed someone who perhaps was

experiencing Secondary Traumatic Stress

who also started seeming professionally

impaired and engaging in improper behavior?

Listen to your warning signs

• If you are distressed, experiencing

some symptoms, you most likely can

still work, but it is CRITICAL that you

address your symptoms head on and

implement a plan for action TODAY

When you could be

dangerous…

• If you fail to address the problem when you

are distressed, this most likely will lead to

impairment and eventually improper behavior

• If you are impaired or exhibit improper

behavior, you ethically should not be

practicing your profession

Practicing prevention

•

•

•

•

•

•

A body-scan exercise

Close your eyes, get comfortable

Breath deeply and slowly from your belly

Start with your head, notice how your head feels, is there any tightness,

pain, tension, stress? Pay attention to those feelings and breath.

Move slowly through the rest of your body. Paying attention to what you

are feeling and where and breathing, relaxing.

The goal is to notice where you are carrying stress from your day and

begin to address it.

Future plans

• Focus groups

• Maybe a psycho-education support

group?

• Other ideas?

Final thoughts?

Thank you!

Please contact us:

Emily Becher, 612-624-3335,

bech0079@umn.edu

Chris Mehus, 651-785-3660,

cjmehus@umn.edu

References

Advisory Committee on Colleague Assistance. (2015). The stress-distressimpairement continuum for psychologists. APA.

http://www.apapracticecentral.org/ce/self-care/colleague-assist.aspx

Bell, H., Kulkarmi, S., & Dalton, L. (2013). Organizational prevention of

vicarious prevention. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary

Social Services, 84(4), 463-470.

Boyle, D.A. (January 31st, 2011). Countering compassion fatigue: A

requisite nursing agenda. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing,

16(1).

•

•

Killian, K.D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of

compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with

trauma survivors. Traumatology: An International Journal, 14(2), 32-44.

Zurbrigen, E. L. (2011). Preventing secondary traumatization in the

undergraduate classroom: Lessons from theory and clinical practice.

Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(3),

223-228.

©2014 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.

The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer.