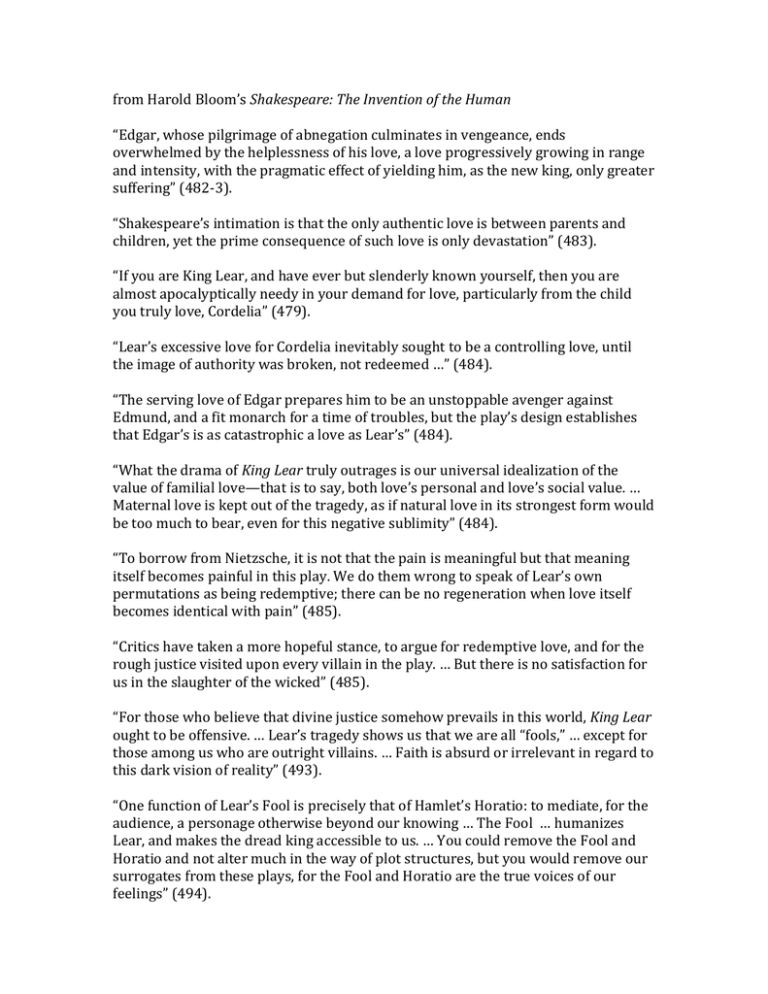

from Harold Bloom's Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human

advertisement

from Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human “Edgar, whose pilgrimage of abnegation culminates in vengeance, ends overwhelmed by the helplessness of his love, a love progressively growing in range and intensity, with the pragmatic effect of yielding him, as the new king, only greater suffering” (482-3). “Shakespeare’s intimation is that the only authentic love is between parents and children, yet the prime consequence of such love is only devastation” (483). “If you are King Lear, and have ever but slenderly known yourself, then you are almost apocalyptically needy in your demand for love, particularly from the child you truly love, Cordelia” (479). “Lear’s excessive love for Cordelia inevitably sought to be a controlling love, until the image of authority was broken, not redeemed …” (484). “The serving love of Edgar prepares him to be an unstoppable avenger against Edmund, and a fit monarch for a time of troubles, but the play’s design establishes that Edgar’s is as catastrophic a love as Lear’s” (484). “What the drama of King Lear truly outrages is our universal idealization of the value of familial love—that is to say, both love’s personal and love’s social value. … Maternal love is kept out of the tragedy, as if natural love in its strongest form would be too much to bear, even for this negative sublimity” (484). “To borrow from Nietzsche, it is not that the pain is meaningful but that meaning itself becomes painful in this play. We do them wrong to speak of Lear’s own permutations as being redemptive; there can be no regeneration when love itself becomes identical with pain” (485). “Critics have taken a more hopeful stance, to argue for redemptive love, and for the rough justice visited upon every villain in the play. … But there is no satisfaction for us in the slaughter of the wicked” (485). “For those who believe that divine justice somehow prevails in this world, King Lear ought to be offensive. … Lear’s tragedy shows us that we are all “fools,” … except for those among us who are outright villains. … Faith is absurd or irrelevant in regard to this dark vision of reality” (493). “One function of Lear’s Fool is precisely that of Hamlet’s Horatio: to mediate, for the audience, a personage otherwise beyond our knowing … The Fool … humanizes Lear, and makes the dread king accessible to us. … You could remove the Fool and Horatio and not alter much in the way of plot structures, but you would remove our surrogates from these plays, for the Fool and Horatio are the true voices of our feelings” (494). “Edmund paradoxically sees himself as overdetermined by his bastardy even as he fiercely affirms his freedom … Though Edmund … cannot reinvent himself wholly, he takes great pride in assuming responsibility for his own amorality, his pure opportunism” (500). Why does the Fool disappear from the play? Why do Edmund and Lear never interact/confront each other? What does Edmund’s change of heart add to the play’s meaning and themes? “Suffering is the true mode of action in King Lear: we suffer with Lear and Gloucester, Cordelia and Edgar, and our suffering is not lessened as, one by one, the evil are cut down … A close reading will find in Lear’s suffering a kind of order, though no idea of order; it is only entropy, human and natural, that is formalized” (505). “Lear, surging on through fury, madness, and clarifying though momentary epiphanies, is the largest figure of love desperately sought and blindly denied ever placed upon a stage or in print. He is the universal image of the unwisdom and destructiveness of paternal love at its most ineffectual, implacably persuaded of its own benignity, totally devoid of self-knowledge, and careening onward until it brings down the person it loves best, and its world as well” (506-7). “Mortality is the ultimate outrage we all of us must endure, and Lear’s authentic prophecy is not against filial ingratitude but against nature, despite his insistence that he speaks for nature. Perpetually outraged, except for the brief idyll of his reconciliation with Cordelia, Lear appeals primordially to the universal outrage of all those acutely conscious of their own mortality” (510). “Lear is overwhelming because he is so close, despite his magnitude. Unless you have firm transcendental beliefs (and Lear loses his), then all you can place against mortality (besides heroic stoicism) is love, whether familial or erotic. Love in this play … is catastrophic. The confusions of domestic love destroy Lear and Gloucester; the murderous and suicidal lust for Edmund of Goneril and Regan could prompt only the dying Edmund, most estranged of souls, to the conclusion that he was beloved. Shakespeare remorselessly makes love itself both outrageous and outraged, in a cosmos centered upon Lear’s needy greatness” (510). “Lear’s troubled authority has foundered where he thought it most absolute: in the relationship with his own daughters” (514). “Lear’s prophecy fuses reason, nature, and society into one great negative image, the inauthentic authority of this great stage of fools. We enter crying at our birth, knowing with Lear that creation and fall are simultaneous” (515). “’Nothing begets nothing’ could be the pragmatic motto of fatherhood in Lear’s play” (515).