revised shunt

advertisement

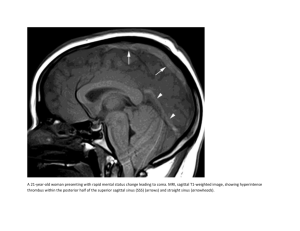

Hydrocephalus & Shunts Sean’s Story What is hydrocephalous? Hydrocephalus is the medical term for a condition that is commonly called “water on the brain.” It is a combination of the Greek word “hydro,” which means water and “cephalus” which means head. However, the liquid involved in hydrocephalus is not really water at all, it is cerebrospinal fluid or CSF. What is CSF? CSF looks like water, but it contains proteins, electrolytes, and nutrients that help keep your brain healthy. The most important purpose of CSF is to cushion your brain and spinal cord against injury. Your brain produces about 1 pint of CSF per day. It circulates through a network of tiny passageways in your brain, and ultimately into your blood stream where it is absorbed by your body. Why does hydrocephalous occur? Hydrocephalus occurs when the delicate balance of CSF production and absorption is disrupted and CSF builds up in the brain. This build-up of CSF causes the brain to swell, and for pressure to increase inside the skull, resulting in nerve damage. Congenital Hydrocephalus People who are born with hydrocephalus have a type of hydrocephalus called congenital hydrocephalus. It is usually caused by a birth defect or by the brain developing in such a way that the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain cannot drain properly. Most cases of hydrocephalus (more than 70%) occur during pregnancy, at birth, or shortly after birth. Causes of congenital hydrocephalus include: Toxoplasmosis (an infection from eating undercooked meat, or by coming in contact with infected soil or an infected animal) Cytomegalovirus (CMV, infection by a type of herpes virus) Rubella (German measles) A genetic disorder usually passed only from mother to son Acquired Hydrocephalus Hydrocephalus can also develop later in life. This type of hydrocephalus is called acquired hydrocephalus, and it can occur when something happens to prevent the CSF in the brain from draining properly. Causes of acquired hydrocephalus include: Blocked CSF flow Brain tumor or cyst Bleeding inside the brain Head trauma Infection (such as meningitis) The cause of Sean’s hydrocephalus Sean suffered a bilateral (both sides) grade 4 (the most severe) intracranial hemorrhage (brain bleed) at 2 days of age due to metabolic acidosis caused from PDA (Patent ductus arteriosus) coupled with the stress from the trauma he experienced at birth. Kaitlyn & Sean The cause of Sean’s hydrocephalus PDA is a heart condition seen in premies (Sean and Kaitlyn were born 10 weeks early) in which the newborn’s DA does not close after birth and there is an irregular transmission of blood between two of the most important arteries in close proximity to the heart. A PDA allows that portion of the oxygenated blood from the left heart to flow back to the lungs. This caused acidic levels to build up in body and, in Sean’s case, caused a severe brain hemorrhage. The large quantity of blood matter mixed with the CSF, slowing its re-absorption and causing hydrocephalus. What is a shunt? A shunt is a piece of soft, flexible plastic tubing that is about 1/8-inch (3mm) in diameter. It allows excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that has built-up inside the skull to drain out into another part of the body, such as the heart or abdomen. To drain excess CSF, shunts are inserted into an opening or pouch inside the brain called a ventricle, just above where the blockage is that is preventing the CSF from flowing properly. How a shunt works All shunts perform two functions. They allow CSF to flow in only one direction, to where it is meant to drain. They all have valves, which regulate the amount of pressure inside the skull. When the pressure inside the skull becomes too great the valve opens, lowering the pressure by allowing excess CSF to drain out. Types of shunts Shunts are named according to where they are inserted in the brain and where they are inserted to let the excess CSF drain out. A ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunt drains into the abdomen or peritoneum (belly). Most shunts, including Sean’s, are VP shunts. A ventriculo-pleural shunt drains into the space surrounding the lung. A ventriculo-atrial (VA) shunt drains into the atria of the heart. The 4 parts of a shunt Ventricular (Upper) CatheterThis is the top-most part of the shunt. It is a small, narrow tube that is inserted into the ventricle (a small opening or pouch) inside the brain that contains the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Reservoir-This is where the excess CSF is collected until it drains into the bottom portion of the shunt. The reservoir also lets the doctor remove samples of CSF for testing, and to inject fluid into the shunt to test for flow and to make sure the shunt is working properly. The 4 parts of a shunt Valve-This controls how much CSF is allowed to drain from the brain. The valve can be set to open at a specific pressure (a fixed pressure valve) or It can be set by the neurosurgeon to meet the individual needs of the person with hydrocephalus (a programmable valve). Lower Catheter-This is the bottom-most part of the shunt. It is a small, narrow tube that carries the excess CSF into the part of the body where it will be absorbed, such as into the abdomen or the heart. Shunt Surgery Small incisions are made on the head and in the abdomen (in case of a VP shunt) to allow the neurosurgeon to pass the shunt's tubing through the fatty tissue just under the skin. A small hole is made in the skull, opening the membranes between the skull and brain to allow the upper catheter to be passed through the brain and into the ventricle. Shunt Surgery The lower catheter is passed into the belly through a small opening in the lining of the abdomen where the excess CSF will eventually be absorbed. The incisions are then closed and sterile bandages are applied. Baby’s 1st Shunt Sean’s first shunt was a reservoir. It worked as an external drain to remove excess CSF and to relieve pressure on the brain. It also helped to remove the blood matter trapped in Sean’s head from the hemorrhage. If left, this blood could clog the shunt and cause it to malfunction, requiring more surgery. Reservoir It contained only the upper portions of the shunt: Ventricular Catheter Reservoir A small needle was used to pierce the skin and tap into the reservoir (a plastic bulb). A syringe was then used to NeedleRESERVOIR: inserted here to drain pull excess CSF from ANCHOR around the brain and to suture in place relieve pressure. VENTRICULAR CATHETER VP Shunt 2 months after the insertion of the reservoir and going through taps 2-3 times a week, Sean had a second surgery to place a VP shunt. This internal system will allow for constant and continual pressure control inside his head without the risk of infection present with constant needle pricks. Sean’s Shunt Line RESERVOIR END HERE with excess coiling for growth Outcomes of shunt surgery Shunt surgery is the most effective treatment for hydrocephalus. By draining excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain, shunt surgery reduces pressure inside the skull lowers the risk of central nervous system damage, and relieves the symptoms associated with hydrocephalus. After effects of shunt surgery Children may need physical or occupational therapy after shunt surgery. Adults may have trouble remembering some things that happened recently (short-term memory). A Lifetime Commitment Once you have a shunt, you always have a shunt. On average, shunts last about 10 years, although they can last for a much longer or much shorter amount of time. A shunt may need to be replaced because of an infection or blockage, or because the shunt valve stops working properly. Fixed pressure shunts, which are preset to a fixed pressure pressure, may need to be replaced if the fixed pressure setting no longer matches the person’s needs. In children, a shunt may need to be replaced as the child grows to lengthen the catheter. Signs that a shunt needs replacing: Loss of appetite Nausea and vomiting Abdominal pain or cramps Changes in mood, including being irritable Frequent or persistent headaches with increased severity Difficulty walking Numbness on one side of the body Muscle tension Sudden, constant, or extreme tiredness Difficulty thinking clearly or remembering Difficulty seeing or speaking Persistent fever Redness, swelling, or tenderness where the shunt is under the skin Coma Difficulty breathing Abnormal heart rate Shunt Revision and Relocation #1 February 2009 The difference a week can make… February 1, 2009 February 8, 2009 Signs of a problem with Sean’s shunt Loss of appetite Nausea and vomiting Abdominal pain or cramps Changes in mood, including being irritable Frequent or persistent headaches with increased severity Difficulty walking Numbness on one side of the body Muscle tension Sudden, constant, or extreme tiredness Difficulty thinking clearly or remembering Difficulty seeing or speaking Persistent fever Redness, swelling, or tenderness where the shunt is under the skin Coma Difficulty breathing Abnormal heart rate (rapid) Surgery #1 Before Surgery Notice swelling in head, including temples. Even eye sockets swollen, forcing eyes down. (Cranial sutures of skull opened up allowing expansion & relieving pressure) After Surgery Shunt removed, EVD placed. (Swelling already gone!) 40 rounds of IV antibiotics 20 rounds of oral antibiotics EVD: External Ventricular Drain The EVD must be kept level with the drain’s end inside Sean’s head. 200 cc (200 mL) of CSF is drained every day – no wonder he had so much swelling & a headache! Surgery #2 24 hours post-op - New shunt in place (Reservoir now in the back of his head) Much happier baby!!!! For more information… Visit www.hydrokids.com