Thinking about knowledge - Geographical Association

advertisement

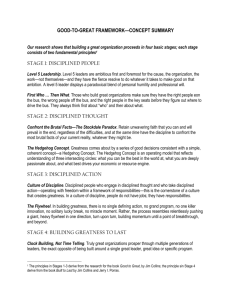

DEPARTMENT Of EDUCATION Thinking about knowledge: Young versus Roberts and beyond GTE Conference Winchester 2014 Why this paper? Issues with Young and Roberts Had shared concerns: e.g. recent curriculum policy context, relevance of disciplinary knowledge/subjects to young peoples’ education, reference to and use of Vygotsky (scientific and everyday concepts) BUT Didn’t seem to recognise the common ground in some of their thinking: social nature of knowledge, there are different types of knowledge in use in the classroom: everyday and disciplinary knowledge Young concerned with the nature of disciplined knowledge, Roberts less so Young explicit and Roberts less so about underpinning theoretical approach to disciplined knowledge: Young: social realism (normative character of thought and knowledge), Roberts: social constructivism??? equal validity? Learning rather than knowledge? There was a good deal of ‘talking past’ each other Why this paper? Listening to some of the student teachers putting forward such insubstantial and polarised arguments during the Q & A session FOR [constructivist] learning and AGAINST knowledge The seminar inspired me to sort out my own thinking 5. The statement on the importance of a broad and balanced curriculum at the start of the draft framework looks tokenistic. instead, a very narrow set of aims has been proposed, which do not appear to consider children in their own right. They are to be provided with ‘core knowledge’ and introduced to ‘the best that has been thought and said’. There is no place for them to be active learners – their role is to accept and internalise what they are told rather than learn to think for themselves. Issues with the theoretical foundations for active learning and with the conceptualisation of knowledge Background themes running through the presentation and questions Tendency for polarised debate about knowledge and often don’t actually talk about the epistemic nature of knowledge Opportunities presented by the NC: how might we support teachers? The influence of constructivism on teachers’ thinking about knowledge abstract parts from the whole which result in distorted understandings of its application Questions 1. What theoretical resources are available [to teacher educators] to help teachers in their thinking about disciplined knowledge? 2. What would constitute an appropriate epistemological stance toward knowledge for students? (Students do have views about knowledge and knowing) My starting point 1. Until recently disciplined knowledge was probably the most neglected and misunderstood idea in education 2. And when we do consider it – we seem to do anything other than actually engage with our conceptions of it – we talk about ‘content’, teachers’ knowledge, learning etc instead 3. As educators we need to think carefully about how we conceptualise knowledge Starting point 4. Recognise that knowledge is important - agree with Michael Young that the question of disciplined knowledge does seem to have disappeared from the theory and practice of curriculum and pedagogy - and does need to be brought back into education RF’s disclaimer - knowledge is not the be all and end all of education but knowledge is important and we need to think about it carefully The subject knowledge of teachers Research has drawn attention to the complexity of the knowledge base of teachers at all phases of education (much of this focused on core subjects), including specialised subject knowledge There has been some research into the knowledge base of geography teachers But no research and little theoretical engagement with conceptualising students knowledge development/development of geographical thinking in terms of epistemic features of disciplined knowledge itself The official and subject specific (geography) discourses of the topic remain rather blunt and simplistic Good news: the question of knowledge is being brought back in Geography Education e.g. Morgan and Lambert (2008), Lambert (2011), Morgan (2011), Catling and Martin, 2011 and my own work, Ben Mayor, Steve Puttick Geographical Association: ‘Knowledge Framework’ developed during the consultation process of the National Curriculum review Geographical Association Knowledge Framework: core, conceptual and procedural (Schwab: syntactic knowledge??) - a simple typology But there is something missing! Disciplinarity – the focus on the nature of disciplined knowledge - what Young has described as ‘powerful knowledge’ i- n the attempt to make the ideas accessible and relevant ‘The time... Seems ripe for some reflection on the roles of knowledge and children’s experience in a subject-based curriculum’ (p. 318). The arguments centre on 4 key ideas: 1. the recognition of different types of knowledge as a basis for the curriculum: everyday-/ethno-knowledge (ethno-geography) and the academic knowledge of disciplines and school subjects 2. the authority relationship between these knowledges in relation to the curriculum and pedagogy 3. the differentiation of types of knowledge as a social justice issue 4. the significance of ethno-geography as a source of geographical knowledge for primary teachers and its implications for teacher education Well worth reading In establishing the case for ethno-knowledge it discusses the nature of knowledge itself – both disciplinary and ethno – in terms of their characteristics Catling and Martin contest the way Young characterises everyday knowledge and privileges disciplinary knowledge as the standard by which to view everyday knowledge Argue that both are rational, conceptual and structured, but differently so Argue that this is not helpful in terms of the primary curriculum nor the subject knowledge of primary teachers. Based on the work of Freire and postcolonial theory What we learn is: Disciplinary knowledge: ‘powerful knowledge’, ‘academic knowledge’, ‘culture of the academy’, ‘generalised’, ‘abstract concepts’, ‘structure’, ‘coherence’, ‘rational, ‘objective’, revised and developed into an abstract body of knowledge that goes beyond the social circumstances of its generation’ (has genesis and development) ethno-knowledge: ‘everyday knowledge’, ‘everyday experiences as a potential source of geographical knowledge’, ‘culture of the everyday’, ‘everyday concepts’, but also ‘objective, ‘powerful’, ‘rational’, ‘reflective upon experience’, ‘has structure and formalised in ways suited to its context’, ‘evolving’ (also has genesis and development) BUT - three points: 1. Appreciate what trying to do, but In establishing the case for ethnoknowledge and encouraging us to reconsider what counts as geographical knowledge disciplinary knowledge moves out of focus 2. This ‘silence’ is not helpful for teachers - primary or secondary: they also need to be encouraged to consider disciplined knowledge 3. No concern with the normative aspect of knowledge and thought – if not valued we lose norms that are at least partially dependent on how the world is 4. Frankenstein and Powell agree with C and M but also note: ‘On the other hand, we need to avoid.. Freire’s tendency toward an uncritical faith in ‘the people’ [which] makes him ambivalent about saying outright that educators can have a theoretical understanding superior to that of the learners and which is, in fact, the indispensable condition of the development of critical consciousness’ ‘We need to do more research to find ways of helping our students learn about their ethno [mathematical] knowledge, contributing to our theoretical knowledge, without denying inequality of knowledge, but as much as possible based on co-operative and democratic principles of equal power’ Disciplinary/disciplined knowledge From content and concepts to episteme We need to raise our eyes beyond the particular ‘subject content’ The discipline is more than bundles of key facts, concepts, explanatory frameworks It has its own characteristic epistemes An episteme: can be described as a system of ideas or ways of understanding that allows us to establish [construct and validate] knowledge Many students will not have heard of epistemes but we deal tacitly with them all the time • Schwab, Bruner, Dewey and Vygotsky have all emphasised the importance of students understanding the epistemic nature of the disciplines they are studying Disciplinary/disciplined knowledge Schwab (1978) distinguishes between substantive and syntactic knowledge Substantive knowledge: key facts, concepts, principles, structures and explanatory frameworks in a discipline Syntactic knowledge: concerns the rules of evidence and warrants of truth within the discipline, the nature of enquiry in the discipline, and how new knowledge is introduced and accepted in that community – in short how to find out and construct knowledge In geography this distinction seems to have been equated to that between content (substantive) and process/enquiry (syntactic). But syntactic knowledge entails greater epistemological awareness than ‘process knowledge’ . We need to recognise and work with syntactic knowledge Disciplinary/disciplined knowledge Constraining constructivism: introducing disciplined judgment (Stemhagen et al, 2013) Focus is preservice teachers In applying constructivist theories to the classroom teachers must skillfully move between student knowledge constructions and disciplinary knowledge and discourses Although the gulf between these two ways of knowing varies markedly by discipline, constructivist approaches are often taught to beginning teachers as if they can be applied uniformly across all subjects We need to critique the use of overly-simplified applications of constructivism in secondary classrooms – what about primary? They illustrate the way constructivist approaches are constrained to differing degrees in the classrooms of three disciplines: English, history, mathematics Disciplinary/disciplined knowledge These arguments apply to geography. We need to: Consider the idea of disciplinary constraint – be concerned with the role of student constructions of knowledge and the limits that must be placed on them Consider the differing existential realities of the tension that teachers must navigate between disciplinary modes of thought and the less formally disciplined beliefs of students Consider the usefulness of the idea of disciplined judgment in teaching and learning geography Disciplinary/disciplined knowledge Disciplined judgment Constructivist classrooms must balance the individual judgments that students apply during the course of their work with the normalising tools of judgment as employed within the discipline Making the criteria of disciplinary judgment explicit will provide a crucial scaffold for students Disciplined judgment is a term that describes the application of criteria that emerge from the institutional context of each discipline to judge the worth of knowledge constructions Rather than seeing this knowledge as a static entity that a learner either acquires, or fails to acquire, disciplinary judgment can help students to understand disciplined knowledge. Thus, a primary challenge to educators is to find ways for students to become skilled, not only at constructing knowledge but also at evaluating it - judging its worth - in disciplined ways. Disciplined judgment The framework, disciplined judgment, is designed to help educators become more aware of their discipline, its unique approach to knowledge, and how to help students learn to employ the normative tools provided by the discipline Rather than attempting to resolve the tension between disciplined and ethno knowledge, the employment of disciplined judgment in a constructivist pedagogy encourages teachers to accept this tension and work with it – it is both inevitable and useful. The tension is useful because it helps bring the knowledge that has been constructed into sharper relief or both teachers and their students Disciplined judgment will lead to metacognition, which itself will lead to a greater understanding and appreciation of the epistemological foundations of the discipline ‘Constructivism’s great contribution to curriculum theory is that it has placed student understanding as the central goal of education. As such, the theory has helped educators to reorient the hierarchical structure of teaching and learning into a more horizontal one in which student constructions of knowledge play a more central role. In choosing to focus on the disciplinary facets of how constructivist teachers appropriately limit student knowledge construction, we are consciously suggesting that answering the question of how teachers can and should influence student knowledge construction requires partially wrestling constructivism writ large from sole possession of educational psychologists and giving it to teachers and disciplinary experts.’ (p. 57) What constitutes an appropriate epistemological stance toward knowledge for students More generic approach (Elby and Hammer, 2001, research based study) Often fail to distinguish between correctness and productivity – a belief is productive if it generates behaviour, attitudes and habits that lead to ‘progress’ – help students learn 4 epistemological dimensions to beliefs about academic/disciplinary knowledge (consensus view underlined): certainty vs. tentativeness; realism vs. relativism; authority vs. independence; simplicity vs. complexity What is accepted within the practices of philosophy, sociology of knowledge and psychology need not be considered accepted in the practices of the discipline What constitutes an epistemological stance toward knowledge for students Elby and Hammer, 2001 Need to attend to context: e.g. A blanket mistrust of authority is no more appropriate/sophisticated than a blanket trust Epistemological sophistication requires student abilities and inclinations to evaluate the trustworthiness of different sources of information Need to distinguish acceptance from understanding Summary Constructivism possesses epistemological, psychological and pedagogical dimensions We need to recognise the relevance of syntactic knowledge to students’ learning We need to be clear about the theoretical underpinnings of how we conceptualise knowledge – and its implications for education: work to do - social constructivism? ‘Transactional realism ‘ Importance of normativity and the inequality of knowledge – teachers need to work with inequality in the classroom Classrooms are based on democratic principles but we should not deny the inequality of knowledge