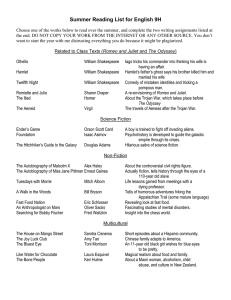

A Room of One's Own

advertisement