Bold Girls Study Materials

advertisement

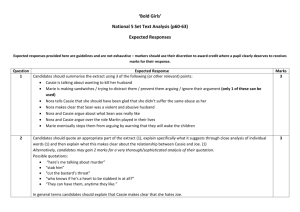

Bold Girls Study Materials What to Expect in the exam: You won’t know which part of the play the extract will come from, so you need to be familiar with the main ideas of the whole play, and know what happens in each scene (use the notes above to help you). Study your grids with information on the characters and what they say - this will be very helpful for the final question, as you will have a good idea of what the main ideas of each scene are so you can refer to them. Read the notes below on each scene, and take notes about the themes and symbols highlighted on page 4. Finally, there is last year’s past paper on Bold Girls to try out. Key Scene Notes Scene 1: Marie’s House The play is set in a world of Belfast drizzle and dreichness; the almost poetic scene directions capture this for the director; ‘it is irons and ironing boards and piles of clothes … socks and pegs and damp sheets …’ Toys everywhere tell us of children, pots and pans of domesticity and the ordinariness and clutter. Two images set out the play’s concerns — the picture of the virgin and the bigger and ‘blownup’ photograph of the as yet unidentified Michael, Marie’s husband … And then there’s Deirdre, crouching outside the room, but outside in further senses, in that she’s meant to be in the darkness of the Belfast streets, but also in the darkness of her hopelessness and of her sorrows. We don’t know who she is; as yet she’s only the wary, young face, speaking a ferocious drama-poetry. Her appearance establishes the next layer of the drama beyond Marie’s positive presence; and tells us that sometimes the play will not be realistic. Deirdre remembers the hills, and singing birds, but can’t see or hear them; the modern streets and the helicopter overhead have come between. Munro won’t attempt to join such sudden surrealism with the main action; it simply happens, then gives way to the main narrative. And Marie comes before us with sheer vigour and integrity. Her children are there — but not allowed to appear, or to diminish our attention to her. Children and men are significantly not allowed to appear at all. Nora appears, with Marie’s towels — and two slight, but important points are made. Wee Michael was supposed to get them, but didn’t; and Nora covers up for his domestic failure — as she always does for men. Cassie shows her sharpness, her earthy sexuality revealing itself in the knickers episode — it doesn’t matter that they are Marie’s, with wee black cats on them saying Hug me, I’m cuddly; it’s Cassie who has highlighted them. All the Bold Girls have appeared, and already the menace of Deirdre, the outsider, should contrast with the apparent normality and friendly banter of the women, centred around Marie, with mother and daughter Nora and Cassie not listening to each other, but revealing their key characteristics — Nora’s harassed and male-dominated domesticity, Cassie’s sharp rejection of it. Munro leaves Deirdre outside; and scene one is ordinary enough, on the surface — kids, washing, fags, whether to go to the club; the topics are mundane. They seem harmless enough Bold Girls, their worst excesses being to do with having too much to drink, or chatting up taxi drivers. Is Nora maybe a bit obsessive about her house and her peach fabric? And where are the men? Clues begin to emerge; ‘Michael’s been dead three and half years’, cries Cassie, urging Marie out, and shocking her mother. Cassie seems unduly nervous of Marie’s ghost-talk of Michael, though significantly none of them are unduly bothered by explosions outside. And what hidden depths to Cassie are revealed in her planting of money behind Michael’s photograph? A major connection is established between Deirdre and Marie with the lighting change which, we’ll come to know, changes the play’s mode from realism to expressionism; first Deirdre, outside, developing her association with greyness, violence, loneliness; then a monologue from Marie, filling us in about her innocence, goodness, and childish optimism in the days when she was first married. We now know that Michael is/was her husband, if little else than that he was charismatic, a bold boy. Munro allows attitudes regarding the Brits, the soldiers who are everywhere, to emerge; cleverly, they are shown early in a good light, so that we don’t get tempted into stereotyping. This set against the ‘thunderous knocking’ at the door which follows the sound of gunshots; although it transpires 1 that this time it’s not the brutal entry of troops, but the unexpected opposite; Deirdre, dirty, battered, looking like fifteen, though eyes heavily made up; second-nameless, unplaceable to the curious women. Again, questions force themselves on us; who on earth is she, with her unnatural toughness and vulnerability? Has she some connection with the violence? Is she a terrorist? She stonewalls all attempts to find her identity — and her fierce knife monologue raises more questions than it reveals. Why is she so bitter? What kind of truth is it she’s after? How has she been able to see the street-violence she clearly knows too well, when, at her age, she should be home with a family? And, once again, where are the men? And at last we begin to hear what’s happened to them. Nora’s Sean is dead (Cassie nostalgic about her father’s gentleness to her), her son Martin and Cassie’s husband Joe are in Long Kesh Terrorist prison. (Isn’t there something odd in the curiously slapstick way Nora and Cassie do a double act about the night Cassie’s husband Joe was arrested? How can they laugh at this horrific treatment of women?) And Marie’s brother Davey seems to be in jail too; while her husband Michael has had his head blown off. Scene one has saved the most horrific revelation for the end; but there are still so many unanswered questions — such as how Michael met his death, who killed him, or why Cassie so misses her father. Marie and Deirdre end the scene; Marie with her moving lullaby to Brendan, rocking him to sleep with her praise of Michael in heaven (but we note Cassie’s unease; why is she suddenly so keen to be out of Belfast?), and her praise of the bold men, ‘all men you’d look at twice’, remembered for their card-playing, drinking, sentimental party singing. It’s intriguing that this mood of remembrance is capped with the reappearance of Deidre. Why is she so changed? How does she know where the hidden money is? And why has Munro chosen to let her steal the scene with this sharply jarring action? We’re left with a final impression of three (or four, if we count Deirdre) separate lines of thought developing. The girls may seem to communicate, but they don’t really listen to each other; there are private selves, motives, and agendas behind the apparent neighbourliness. Scene 2: The Club Again, stage directions are vivid and atmospheric; it’s worth briefly assessing just how significant they are, and just how much they help fix our responses to what follows. There’s a clever opening here, in which we as audience have to find our feet as regards what’s going on. Who’s being talked about? Why are they standing? It’s an effective way of underlining the repetitiveness of the violence — this has happened many times. And it reminds Marie of coffins — and Michael? The club, with its garish decor and its get-rich-quick games, is an appropriate place for the girls to recall their men and the famous wall-and-dog story, and by now sensitive response to the play is questioning whether these memories can be taken at face value. After all, Nora’s husband cheated in betting, and Michael lost his car. Isn’t there something a bit strained about the brave face memory puts on? Isn’t Cassie showing more and more that she’s hardly got sorrowful feelings about ‘the dear departed’? And isn’t something a bit strained about the toast to the bold girls by themselves? Again, we note the three simultaneous lines of topic; ‘Guess the Price’, Nora and Cassie’s sniping, the discussions of Deirdre’s boldness in Marie’s clothes all run together, intermingled. It’s a clever way of mingling themes. The materialism which defines Nora and Cassie emerges in the first (‘Oh Mummy! She’s won the magi-mix!’ shows that the world of prizes and things can bring them to agreement); in the second, we learn more of Nora’s survival toughness from her strange treatment of the past in her anecdotes (which are almost monologues — serving what purpose?), and of Cassie’s bitterness. What is Cassie’s brazen dance really saying? And, in the third line, after the raid which freezes time and the club, releasing Marie and Deirdre into a kind of shared, stylised dialogue, we ask more questions about what’s making Deirdre the utterly unfeeling and amoral person she seems to be. It’s becoming clear now that Cassie’s dislike of Deirdre has deeper undertones to it than simple loyalty to her friend. The past is here too, in Marie’s uncanny feeling of having seen Deirdre before. Is Deirdre here to have something out? With Marie or Cassie? Why does she not defend herself against Cassie’s final attack? 2 And why does the scene end, not with the drama we’ve been witnessing, but with an oddly placed stylised monologue from Nora deriding the use of talk, and leaving us with her obsessive yearning for fifteen yards of pale peach polyester fabric? Scene 3: Outside the Club This short scene, three pages of dialogue between Marie and Cassie, with a typically wordless, brief and nasty contribution from Deirdre at the end, poses questions. Just why is it so unbalanced with the rest of the play, so disproportionate in size? Why change from interior setting of house and club to wasteland and moonlight? Is there significant and symbolic connection with what’s happening between Marie and Cassie (and with all the bold girls) in the fact that there’s an eclipse of the moon — ‘our very own shadow swallowing up all the light’? A simple enough answer to the first question regarding length might suggest that staging considerations call for time to allow the resetting of Marie’s house for scene 4; that said, Munro is far too skilful a dramatist to allow mere stage necessity to dominate. Marie and Cassie here show their closeness; there is a great strength in this bonding, a strength which has supported all of them in hard times. But there is a crack in this togetherness; and this wedge of a scene drives home the first real division between them all, a knife-point which will come close to destroying them all by the end. Cassie’s ‘Aw Jesus I hate this place!’ as she kicks the very ground she lives on, her agonised desire to leave, and Marie’s reminder of the claims of children, reinforce our awareness of Cassie’s tortured heart and Marie’s (self-deceiving?) goodness. Do all the bold girls have some kind of self-deluding dream? Don’t Marie, Nora, Cassie — and even Deirdre — all in the end reveal that they are holding on to some kind of consoling dream of past or future? Certainly Deirdre, stealer of purses, seems more of a straightforward destroyer as she finds her longed-for knife and slashes at Nora’s dream-fabric. But, looking deeper, can’t we see that she too is following a kind of distorted dream? Scene 4: Marie’s House Our impression of Marie’s steady goodness is reinforced by the picture of her feeding birds in the pitch blackness, while Nora and Cassie continue to drink. (Do you think that Munro means us to see drink as one of the major problems in this play?) A latent hostility between Nora and Cassie comes to a head in this scene of many climaxes, as memories of the menfolk — and a new ugliness, that of wife-beating — surfaces through the alcoholic haze. With the discovery that her hidden money, the dream-of-escape-money, is gone, the antagonism (is it indeed hatred?) between mother and daughter explodes, and we see the resentment of years, with Cassie’s comment that her mother’s heart is made of steel, a condemnation oddly qualified with understanding — ‘she had to grow it that way’. Have we been prepared for the horrific admissions from Cassie which follow? Has Munro planted enough clues to suggest to us that deep down we aren’t surprised? Remember, however, when considering Cassie’s betrayal of Marie, what Deirdre will say about Cassie’s appearance when making love with Michael; ‘she looked like my grandmother, old and tired and like she didn’t care about anything at all anymore…’. Does this help us to understand Cassie’s betrayal of her best friend? Unusually, the play has yet another ending; perhaps more important than the revelation of Cassie’s affair with Michael. Deirdre comes back from what may have been an attempt to rape her, after the club closed. She brings back most of the stolen money — and her knife. She seems poised between attacking Marie and talking to her — poised, perhaps, between two different kinds of ‘hard truth’? Her choice has to wait; after revealing to Marie that Michael is her father, she wants some kind of confirmation from her. But can Marie ever give Deirdre the ‘truth’ she’s after? She can destroy Michael’s photograph, and her own and Deirdre’s remaining illusions, she can tell her that she does look like Michael, and what Michael had for tea, and that someone — Provos, enemies, does it ultimately matter? — ‘took the lying head off him’; but the truth about Michael, and Cassie’s father, and all the other men implicated in their lives, will surely remain elusive, as Marie’s last big speech about ‘all the daddys’ admits. All that can be hoped is that ‘we learn some way to change’, in our dealings with each other, women to women, men to men, and women and men to each other. How far does Marie reveal in these closing stages that she isn’t and has never really been the trusting innocent, the feeder of birds? How far — and why — has she been living a lie? And how far can we read the end, with its partial reconciliation of Deirdre and her sorrows with Marie and hers, as optimistic? What is the significance of the play’s closing actions, the return to ordinary domesticity and the feeding of the birds? 3 Themes Images and symbols Take notes on the importance of the following: * Nora’s peach fabric * Deirdre’s knife * the birds that are fed by Marie * the pictures (The Virgin Mary and Michael) on Marie’s walls. Values of contemporary society To what extent is Cassie an example of the hopes and desires of young women? What does she want out of life? What prevents her from getting what she wants? Cassie’s story is affected by the Troubles, but in fact she could be any young woman living in any rundown estate in any town in Scotland. Looking at what she tells us in the play: How is she influenced by television and magazines? Are the things she wants within her reach? Truth and illusion This is a play about women living in a ‘war zone’, struggling with poverty and difficult social conditions, as single parents. One of the strategies adopted by Nora, Marie and Cassie is the avoidance of truth and the creation of a comforting illusion. Taking each character in turn, and paying close reference to the text, consider what illusions they create and what truths they avoid. For example, Nora is exceptionally house proud – look at the references to her fabric and to the lamented bamboo suite that was destroyed by the British soldiers. What sort of magazines do you think she would read? What would her favourite programme on daytime television be? If Nora could have a dream come true, what do you think it would be? On the other hand, what is going wrong in Nora’s life? To what extent does she face up to the truth of this or hide behind a dream? Think about the significance of Deidre’s knife. She refers to a knife as ‘a wee bit of hard truth you could hold in your hand and pint where you liked’. Why do you think truth is important to Deirdre? Think about her background and upbringing. The play is full of examples of lies and deceit. List as many examples of lies and the concealing of information as you can. Does everyone have a secret? Bold girls and bold boys: gender issues * Why do you think the play is entitled Bold Girls? * What messages about women’s lives and the challenges they have to face does Rona Munro give the audience? Identify three incidents from the play that illustrate this. * What messages about men’s lives does the writer give the audience? While the men do not appear on stage, identify one thing each of the women tell us about their men (Michael, Sean, Joe and Martin) that illustrate this? 4 Last Year’s Past Paper – 2014 5 6