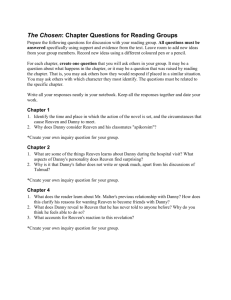

literature summaries about teaching and learning

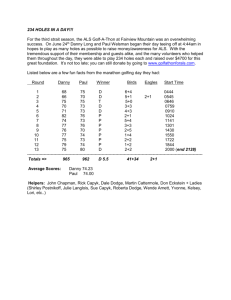

advertisement

The Chosen By Chaim Potok The Chosen begins in 1944 with a softball game in a Jewish section of Brooklyn, New York, between students from two Jewish parochial schools. Each team represents a different Jewish sect with a different level of religious observance. Danny Saunders represents a Hasidic sect led by his father, Reb (short for rabbi) Saunders. Reuven Malter leads the opposing team, which is composed of Modern Orthodox Jews, who are not as ultra-Orthodox in terms of their religious observances as Hasidic Jews are. Reuven is the son of David Malter, a yeshiva professor. During the game, Danny hits a ball that strikes Reuven in the face, injuring his eye and sending him to the hospital for surgery. Danny visits Reuven in the hospital and apologizes for hitting him with the ball. At first, Reuven rejects Danny's apology, but at the urging of his father, he becomes Danny's friend. Speaking of himself, Danny tells Reuven that he will inherit his father's position, as is common in the Hasidic tradition, and become a rabbi, but he also admits that he would rather become a psychologist. Reuven learns that Danny has been raised in virtual silence — the only time Reb Saunders talks to his son is when they study Talmud together. Danny confesses that studying only the Talmud is boring and that he secretly reads secular books in the public library. According to Danny, even though Jews have an obligation to obey God, sometimes he is not sure what God wants. Reuven wants to become a rabbi but also has a strong interest in math. Danny makes the perceptive and rather amusing observation that he has to be a rabbi but doesn't want to be one, and Reuven does not have to be a rabbi but wants to be one. Reuven visits Danny at his home several times and discusses the Torah and other writings with Reb Saunders and Danny. During one of these visits, Reb Saunders talks to Reuven privately. The Reb says that he knows that Danny has been visiting the public library and wants to know what he has been reading. Reuven tells Reb Saunders everything — how Danny met Mr. Malter in the library and how his father helped Danny select reading material. The Reb says that Danny is so brilliant that he cannot talk to him, but he also says with deep emotion that Danny is his most precious possession. When Mr. Malter suffers a heart attack, Reb Saunders invites Reuven to stay with him and his family until Mr. Malter's health improves. Danny and Reuven spend much time together discussing various literary and Jewish subjects. When they visit Reuven's father in the hospital, Mr. Malter talks passionately about the 6 million Jews slaughtered by Hitler and the Nazis and how the American Jews must help rebuild this human loss. He also supports establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. Jews cannot wait for the Messiah to come to aid them, he argues. They must help themselves. Mr. Malter's position on Palestine contrasts that of Reb Saunders, who says that Palestine cannot become a Jewish state until the Messiah comes. Danny and Reuven enter Hirsch College for the fall term. Danny is upset that the college psychology department discredits the work of Sigmund Freud, preferring instead the discipline of experimental psychology. Mr. Malter gives a speech at Madison Square Garden in New York City, urging an end to British control of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish state in its place. Reuven is moved by the speech, but Reb Saunders is furious. He forbids Danny to associate with Reuven. Reuven tells his father about this, adding that it wasn't unexpected. Reuven says to his father that Reb Saunders is a fanatic. Mr. Malter agrees but adds that the fanaticism of people like Reb Saunders has kept the Jewish people alive for the last 2,000 years. For the rest of the semester, Danny and Reuven do not speak to one another. Reuven finds the estrangement terrible to endure — his grades suffer, and he constantly wonders what Danny is thinking and how he's getting along. The conflict between Reb Saunders and Mr. Malter continues. Reb Saunders organizes his followers into a group called the League for a Religious Israel. Mr. Malter continues speaking on behalf of a Jewish state in Palestine. On November 29, 1947, the United Nations decides to partition Palestine into an Arab state and a Jewish state. Reb Saunders condemns the United Nations' announcement and orders Jews to ignore it. The state of Israel is formally proclaimed on May 14, 1948. After the United Nation's action, Reb Saunders' antiZionist stance fades in importance as far as the students at Hirsch College are concerned. Danny is again permitted to speak to Reuven, and their rift is healed. At his professor's suggestion, Danny decides to pursue a Ph.D. in clinical psychology, which means that he will have to renounce his claim to his father's rabbinical position. Danny and Reuven discuss how Danny should tell his father, and Danny also gets advice from Mr. Malter. Ironically, Reb Saunders already knows of Danny's decision. Through Danny, Reb Saunders invites Reuven to his home for the Passover holiday, and the two young men talk together with Reb Saunders. The Reb recognizes that the boys have become men. Reuven tells the Reb that he is going to become a rabbi. Reb Saunders acknowledges that Danny has chosen a different path; Danny has a brilliant mind and cannot be satisfied within the confines of a Hasidic environment. The Reb trusts that Danny will become a tzaddik for the world in his practice of psychology. Danny and Reuven graduate from Hirsch College. When Danny comes to say good-bye to Reuven and Mr. Malter before leaving for graduate school at Columbia University, Reuven notices that Danny has shaved his beard and cut off his earlocks, two symbols of the Hasidic faith. Mr. Malter says that Columbia University is not so far away, so Danny should visit them often. The novel ends as Danny agrees to visit the Malters and then leaves. The Education of Little Tree by Forrest Carter After his parents die, a young boy called Little Tree is raised by his Cherokee grandparents in the mountains of Eastern Tennessee during the 1930s. The novel follows Little Tree's daily life as he helps his grandparents learn to stand up for their rights, and in the process he learns a great deal about standing up for his own. As the novel progresses, Little Tree describes the simple life lessons he learns by living in touch with Nature. The Apt Pupil by Stephen King In 1974, Todd Bowden arrives at the doorstep of elderly German immigrant Arthur Denker, accusing him of being a wanted Nazi war criminal named Kurt Dussander. The old man initially denies the allegation, but eventually acknowledges his true identity. But rather than turning Dussander over to the proper authorities, Todd asks to hear highly detailed stories about his crimes, having recently become interested in the Holocaust. However, Todd still threatens Dussander with exposure should he refuse his demands. Over the next several months, Todd visits Dussander daily under the pretext of reading to him, all the while badgering him into revealing more details of his atrocities. Todd soon gives Dussander an SS Obersturmbannführer's uniform, forcing him to wear it and march on command. As his relationship with Dussander continues, Todd also begins to have nightmares and sees his grades slip. After being confronted by his father about his grades, he forges his report cards before giving them to his parents. Eventually, Todd becomes in danger of flunking several courses. This causes Ed French, Todd's guidance counselor, to seek an appointment with the Bowdens. Todd and Dussander concoct a ruse, having Dussander go to French's appointment while posing as Todd's grandfather, Victor. Dussander falsely claims that Todd's grades are the result of problems at home, and promises to make sure his grades improve; French believes Dussander's story, but notices that Todd's "grandfather" does not mention him by name. Knowing that Todd has been doctoring his report cards and knowingly socialized with a war criminal, Dussander blackmails Todd into spending his visits studying. With great effort, Todd is able to sufficiently improve his schoolwork. Since he no longer has any use for Dussander, Todd resolves to kill him and make it look like an accident. Todd had earlier claimed to have given a letter about Dussander to a friend; if anything should happen to Todd, the letter will be sent to the authorities. However, before Todd can kill Dussander, the old man claims to have written about Todd's involvement with him, and put his statement into a safe deposit box that will be found upon his death. Over the next few months, Todd murders several homeless vagrants; he finds that committing murder somehow helps with his nightmares. As years pass, Todd's visits to Dussander become less frequent. He loses his virginity, but finds sex unsatisfying compared to the thrill of murdering local derelicts. When circumstances do not allow him to continue his serial killings, he picks a concealed spot overlooking the freeway and aims at people in passing cars with his hunting rifle. Dussander, suffering from his own nightmares, has also taken to killing the homeless for essentially the same reason as Todd, burying the bodies in his basement. Despite the link between them, Dussander and Todd are not immediately aware of each other's exploits. One night, when Dussander is digging a grave for his latest victim, he has a heart attack. He summons Todd, who buries the body and cleans up the crime scene before finally calling an ambulance. At the hospital, Dussander happens to share a room with Morris Heisel, an elderly Jewish man who recognizes "Mr. Denker", but cannot place him. When Todd visits Dussander in the hospital, Dussander admits he was bluffing about the bank deposit box, as was Todd's threat about his letter. Dussander has read about the homeless men murdered by Todd, and tells the boy not to get careless. Dussander declares that "we are quits." A few days later, Heisel realizes that Denker is Dussander, the commandant of the camp where his wife and daughters died in the gas chambers. An Israeli Nazi hunter named Weiskopf visits Dussander, telling him that he has been found out. After Weiskopf leaves, Dussander steals some drugs from the hospital dispensary and commits suicide. When Dussander's identity is revealed to the world, Todd convinces his parents that he didn't know about Dussander's past. Meanwhile a police detective named Richler, accompanied by Weiskopf, interviews Todd and is not so easily convinced. A vagrant recognizes Todd as the last person seen with several of the homeless victims, and notifies the police. Meanwhile, French meets Todd's real grandfather. French brings up their previous conversation, but the real Victor Bowden obviously doesn't recall their meeting. French becomes suspicious and checks Todd's old report cards, finding that they have been tampered with. Later, he identifies the late Kurt Dussander as the man who met with him about Todd's grades. French confronts Todd, who responds by fatally shooting him. Todd then takes his rifle and ammunition to his hideout by the freeway. He embarks on a shooting spree, resulting in his death at the hands of the authorities five hours later. Education for Extinction by David Wallace Adams Education for Extinction is a poignant and heartbreaking book that chronicles the infamous history of the U.S. government's efforts to indoctrinate, deculturalize, and "Americanize" Native peoples through the use of boarding schools. Under the guise of "progress" and "civilization," thousands of native children were forcefully removed from their families and cultures, and deprived of their peoples' history. This book testifies to both the cruelties perpetrated against the hearts and minds of children and to the many acts of courage and resistance performed by these children. The genesis of U.S. government policy towards Native people began in the 1780s. The prevailing Lockean mentality held that only a society established on a consensus of private property could promote social stability, political independence, and public morality. As Adams notes: Whether discussing the Indians' worship of pagan gods, their simple organizations, or their dependency on wild game for subsistence, white observers found Indian society wanting. Indian life, it was argued, constituted a lower order of human society. In a word, Indians were savages because they lacked the very thing whites possessed--civilization. And since, by the law of historical progress and the doctrine of social evolution, civilized ways were destined to triumph over savagism, Indians would ultimately confront a fateful choice: civilization or extinction. (pp. 5-6) After almost a century of checkered policies (Indian removal, broken treaties, and bloody warfare), in 1871, Congress deemed Native peoples to be wards of the government, a de facto colonized people. The concept of Indian education was proposed by reformers in the 1870s and soon gained support among government officials and the public. The aims of Indian education were several: one, to provide Indian children with the rudiments of an academic education, including reading, writing, and speaking English; two, Indians needed to be individualized, as reformers felt that tribal life placed more importance on the tribal community than on the individual; and third, Indian education was Americanization. It was within this context that, in 1877, Congress began to appropriate funds expressly for Indian education. The boarding schools were primarily of two types: reservation schools and off-reservation schools. The typical teacher in the Indian schools was a single White woman in her late twenties, partly because teaching had been defined as "women's work," and partly because women were less expensive to employ than men. In the schools, the assault on the cultural identity of Indian children began with a haircut (to look more like White children), a change of the students' dress (usually a uniform), and the assignation of European names. So as not to contaminate the process of Americanization, Indian languages, customs, and religions were prohibited, and parental visits were discouraged. Both boys and girls were subjected to daily marching drills, presumably to exterminate their innate "wildness." They were also subjected to corporal punishment. Students who resisted or refused to conform to the school rules were remanded to the school "jail" or "guardhouse." Students suffered from either malnourishment, which arose from extreme dietary changes, or undernourishment, due to limited supplies of food. Diseases were rampant, because of dietary problems and because of the shoddy construction and dilapidated conditions of the school buildings, largely a result of corrupt Bureau of Indian Affairs bureaucrats who embezzled or misappropriated government school funds. Indian children and their home communities resisted their attempts at deculturalization. As Adams explains, "a major motivation for resistance, [was] namely, that a significant body of tribal opinion saw white education for what it was: an invitation to cultural suicide" (p. 212). He continues: Students resisted for several reasons. First, there was the deep resentment occasioned by the institution itself. . . . Second, resistance was in part political. For older students especially, it took little imagination to discern that the entire school program constituted an uncompromising hegemonic assault on their cultural identity. . . . Finally, resistance can be explained in psychological terms. In the context of severe cultural conflict, students were experiencing education in terms of what anthropologists have come to call "acculturation stress," "cultural discontinuity" and "cognitive dissonance." (p. 223) Despite daily humiliation, many children's spirits remained unbroken; they remained "patriots" to their own people. They resisted attempts to "Americanization" by running away, committing arson, and, most pervasively, through acts of passive resistance (i.e., acts of defiance, class disruptions, "work slow downs," unresponsiveness). Still others clandestinely kept alive and taught others their languages, customs, rituals, and history. Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut It is the year 2081. Because of Amendments 211, 212, and 213 to the Constitution, every American is fully equal, meaning that no one is stupider, uglier, weaker, or slower than anyone else. The Handicapper General and a team of agents ensure that the laws of equality are enforced. One April, fourteen-year-old Harrison Bergeron is taken away from his parents, George and Hazel, by the government. George and Hazel aren’t fully aware of the tragedy. Hazel’s lack of awareness is due to average intelligence. In 2081, those who possess average intelligence are unable to think for extended stretches of time. George can’t comprehend the tragedy because the law requires him to wear a radio twenty-four hours a day. The government broadcasts noise over these radios to interrupt the thoughts of intelligent people like George. Hazel and George are watching ballerinas dance on TV. Hazel has been crying, but she can’t remember why. She remarks on the prettiness of the dance. For a few moments, George reflects on the dancers, who are weighed down to counteract their gracefulness and masked to counteract their good looks. They have been handicapped so that TV viewers won’t feel bad about their own appearance. Because of their handicaps, the dancers aren’t very good. A noise interrupts George’s thoughts. Two of the dancers onscreen hear the noise, too; apparently, they are smart and must wear radios as well. Hazel says she would enjoy hearing the noises that the handicappers dream up. George seems skeptical. If she were Handicapper General, Hazel says, she would create a chime noise to use on Sundays, which she thinks would produce a religious effect. The narrator explains that Hazel strongly resembles Diana Moon Glampers, Handicapper General. Hazel says she would be a good Handicapper General, because she knows what normalcy is. Before being interrupted by another noise, George thinks of his son, Harrison. Hazel thinks George looks exhausted and urges him to lie down and rest his “handicap bag,” forty-seven pounds of weight placed in a bag and locked around George’s neck. He says he hardly notices the weight anymore. Hazel suggests taking a few of the weights out of the bag, but he says if everyone broke the law, society would return to its old competitive ways. Hazel says she would hate that. A noise interrupts the conversation, and George can’t remember what they were talking about. On TV, an announcer with a speech impediment attempts to read a bulletin. He can’t overcome his impediment, so he hands the bulletin to a ballerina to read. Hazel commends him for working with his God-given abilities and says he should get a raise simply for trying so hard. The ballerina begins reading in her natural, beautiful voice, then apologizes and switches to a growly voice that won’t make anyone jealous. The bulletin says that Harrison has escaped from prison. A photo of Harrison appears on the screen. He is wearing the handicaps meant to counteract his strength, intelligence, and good looks. The photo shows that he is seven feet tall and covered in 300 pounds of metal. He is wearing huge earphones, rather than a small radio, and big glasses meant to blind him and give him headaches. He is also wearing a red rubber nose and black caps over his teeth. His eyebrows are shaved off. After a rumbling noise, the photo on the Bergerons’ TV screen is replaced with an image of Harrison himself, who has stormed the studio. He says that he is the emperor, the greatest ruler in history, and that everyone must obey him. Then he rips off all of his handicaps. He looks like a god. He says that the first woman brave enough to stand up will be his empress. A ballerina rises to her feet. Harrison removes her handicaps and mask, revealing a beautiful woman. He orders the musicians to play, saying he will make them royalty if they do their best. Unhappy with their initial attempt, Harrison conducts, waving a couple of musicians in the air like batons, and sings. They try again and do better. After listening to the music, Harrison and his empress dance. Defying gravity, they move through the air, flying thirty feet upward to the ceiling, which they kiss. Then, still in the air, they kiss each other. Diana Moon Glampers comes into the studio and kills Harrison and the empress with a shotgun. Training the gun on the musicians, she orders them to put their handicaps on. The Bergerons’ screen goes dark. George, who has left the room to get a beer, returns and asks Hazel why she has been crying. She says something sad happened on TV, but she can’t remember exactly what. He urges her not to remember sad things. A noise sounds in George’s head, and Hazel says it sounded like a doozy. He says she can say that again, and she repeats that it sounded like a doozy. The Lord of the Flies by William Golding In the midst of a raging war, a plane evacuating a group of schoolboys from Britain is shot down over a deserted tropical island. Two of the boys, Ralph and Piggy, discover a conch shell on the beach, and Piggy realizes it could be used as a horn to summon the other boys. Once assembled, the boys set about electing a leader and devising a way to be rescued. They choose Ralph as their leader, and Ralph appoints another boy, Jack, to be in charge of the boys who will hunt food for the entire group. Ralph, Jack, and another boy, Simon, set off on an expedition to explore the island. When they return, Ralph declares that they must light a signal fire to attract the attention of passing ships. The boys succeed in igniting some dead wood by focusing sunlight through the lenses of Piggy’s eyeglasses. However, the boys pay more attention to playing than to monitoring the fire, and the flames quickly engulf the forest. A large swath of dead wood burns out of control, and one of the youngest boys in the group disappears, presumably having burned to death. At first, the boys enjoy their life without grown-ups and spend much of their time splashing in the water and playing games. Ralph, however, complains that they should be maintaining the signal fire and building huts for shelter. The hunters fail in their attempt to catch a wild pig, but their leader, Jack, becomes increasingly preoccupied with the act of hunting. When a ship passes by on the horizon one day, Ralph and Piggy notice, to their horror, that the signal fire—which had been the hunters’ responsibility to maintain—has burned out. Furious, Ralph accosts Jack, but the hunter has just returned with his first kill, and all the hunters seem gripped with a strange frenzy, reenacting the chase in a kind of wild dance. Piggy criticizes Jack, who hits Piggy across the face. Ralph blows the conch shell and reprimands the boys in a speech intended to restore order. At the meeting, it quickly becomes clear that some of the boys have started to become afraid. The littlest boys, known as “littluns,” have been troubled by nightmares from the beginning, and more and more boys now believe that there is some sort of beast or monster lurking on the island. The older boys try to convince the others at the meeting to think rationally, asking where such a monster could possibly hide during the daytime. One of the littluns suggests that it hides in the sea—a proposition that terrifies the entire group. Not long after the meeting, some military planes engage in a battle high above the island. The boys, asleep below, do not notice the flashing lights and explosions in the clouds. A parachutist drifts to earth on the signal-fire mountain, dead. Sam and Eric, the twins responsible for watching the fire at night, are asleep and do not see the parachutist land. When the twins wake up, they see the enormous silhouette of his parachute and hear the strange flapping noises it makes. Thinking the island beast is at hand, they rush back to the camp in terror and report that the beast has attacked them. The boys organize a hunting expedition to search for the monster. Jack and Ralph, who are increasingly at odds, travel up the mountain. They see the silhouette of the parachute from a distance and think that it looks like a huge, deformed ape. The group holds a meeting at which Jack and Ralph tell the others of the sighting. Jack says that Ralph is a coward and that he should be removed from office, but the other boys refuse to vote Ralph out of power. Jack angrily runs away down the beach, calling all the hunters to join him. Ralph rallies the remaining boys to build a new signal fire, this time on the beach rather than on the mountain. They obey, but before they have finished the task, most of them have slipped away to join Jack. Jack declares himself the leader of the new tribe of hunters and organizes a hunt and a violent, ritual slaughter of a sow to solemnize the occasion. The hunters then decapitate the sow and place its head on a sharpened stake in the jungle as an offering to the beast. Later, encountering the bloody, fly-covered head, Simon has a terrible vision, during which it seems to him that the head is speaking. The voice, which he imagines as belonging to the Lord of the Flies, says that Simon will never escape him, for he exists within all men. Simon faints. When he wakes up, he goes to the mountain, where he sees the dead parachutist. Understanding then that the beast does not exist externally but rather within each individual boy, Simon travels to the beach to tell the others what he has seen. But the others are in the midst of a chaotic revelry—even Ralph and Piggy have joined Jack’s feast—and when they see Simon’s shadowy figure emerge from the jungle, they fall upon him and kill him with their bare hands and teeth. The following morning, Ralph and Piggy discuss what they have done. Jack’s hunters attack them and their few followers and steal Piggy’s glasses in the process. Ralph’s group travels to Jack’s stronghold in an attempt to make Jack see reason, but Jack orders Sam and Eric tied up and fights with Ralph. In the ensuing battle, one boy, Roger, rolls a boulder down the mountain, killing Piggy and shattering the conch shell. Ralph barely manages to escape a torrent of spears. Ralph hides for the rest of the night and the following day, while the others hunt him like an animal. Jack has the other boys ignite the forest in order to smoke Ralph out of his hiding place. Ralph stays in the forest, where he discovers and destroys the sow’s head, but eventually, he is forced out onto the beach, where he knows the other boys will soon arrive to kill him. Ralph collapses in exhaustion, but when he looks up, he sees a British naval officer standing over him. The officer’s ship noticed the fire raging in the jungle. The other boys reach the beach and stop in their tracks at the sight of the officer. Amazed at the spectacle of this group of bloodthirsty, savage children, the officer asks Ralph to explain. Ralph is overwhelmed by the knowledge that he is safe but, thinking about what has happened on the island, he begins to weep. The other boys begin to sob as well. The officer turns his back so that the boys may regain their composure.