Week 3 Historical Survey 1: Ancient Greek Theatre

advertisement

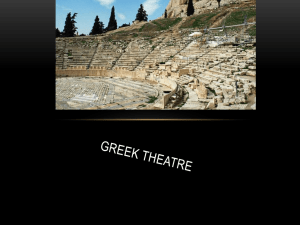

Week 3 Historical Survey 1: Ancient Greek Theatre Ancient Greek theatre is the origin and matrix of the Western theatre. First time in history, great playwrights established the autonomous form and structure of drama, and a grandscale spectacle for the whole community was created by integrating music and dance. Comedy and tragedy were already accepted as different genres in practice, and Aristotle formulated a great theoretical foundation on the aesthetics of drama regarding tragedy and (a little bit of) comedy. Theatre architecture also showed its first appearance and continued its influence in Hellenized and Roman era. Overall, the ancient Greek theatre in all aspects (works, theory, architecture, staging conventions) made a great impact on the Renaissance theatre in theory and practice, and its breath is still felt today. 1. Timeline of Greek Drama Although the origins of Greek Tragedy and Comedy are obscure and controversial, our ancient sources allow us to construct a rough chronology of some of the steps in their development. Some of the names and events on the timeline are linked to passages in the next section on the Origins of Greek Drama which provide additional context. 7th Century BC c. 625 Arion at Corinth produces named dithyrambic choruses. 6th Century BC 600-570 540-527 536-533 525 511-508 c. 500 Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sicyon, transfers "tragic choruses" to Dionysus Pisistratus, tyrant of Athens, founds the festival of the Greater Dionysia Thespis puts on tragedy at festival of the Greater Dionysia in Athens Aeschylus born Phrynichus' first victory in tragedy Pratinus of Phlius introduces the satyr play to Athens 5th Century BC 499-496 c. 496 492 485 484 472 467 468 463? 458 456 c. 450 447 c. 445 441 438 431-404 431 Aeschylus' first dramatic competition Sophocles born Phrynicus' Capture of Miletus (Miletus was captured by the Persians in 494) Euripides born Aeschylus' first dramatic victory Aeschylus' Persians Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes Aeschylus defeated by Sophocles in dramatic competition Aeschylus' Suppliant Women Aeschylus' Oresteia (Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides) Aeschylus dies Aristophanes born Parthenon begun in Athens Sophocles' Ajax Sophocles' Antigone Euripides' Alcestis Peloponnesian War (Athens and allies vs. Sparta and allies) Euripides' Medea c. 429 428 423 415 406 405 404 401 Sophocles' Oedipus the King Euripides' Hippolytus Aristophanes' Clouds Euripides' Trojan Women Euripides dies; Sophocles dies Euripides' Bacchae Athens loses Peloponnesian War to Sparta Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus 4th Century BC 399 c. 380's c. 330's Trial and death of Socrates Plato's Republic includes critique of Greek tragedy and comedy Aristotle's Poetics includes defense of Greek tragedy and comedy 2. Origins of Greek Drama Aristotle and a number of other writers proposed theories of how tragedy and comedy developed, and told stories about the people thought to be responsible for their development. Here are some excerpts from Aristotle and other authors which show what the ancient Greeks thought about the origins of tragedy and comedy. Aristotle on the origins of Tragedy and Comedy 1. Indeed, some say that dramas are so called, because their authors represent the characters as "doing" them (drôntes). And it is on this basis that the Dorians [= the Spartans, etc.] lay claim to the invention of both tragedy and comedy. For comedy is claimed by the Megarians here in Greece, who say it began among them at the time when they became a democracy [c. 580 BC], and by the Megarians of Sicily on the grounds that the poet Epicharmas came from there and was much earlier than Chionides and Magnes; while tragedy is claimed by certain Dorians of the Peloponnese. They offer the words as evidence, noting that outlying villages, called dêmoi by the Athenians, are called kômai by them, and alleging that kômôdoi (comedians) acquired their name, not from kômazein (to revel), but from the fact that, being expelled in disgrace from the city, they wandered from village to village. The Dorians further point out that their word for "to do" is drân, whereas the Athenians use prattein. (Aristotle: Poetics Chapter 3) 2. And in accordance with their individual types of character, poetry split into two kinds, for the graver spirits tended to imitate noble actions and noble persons performing them, and the more frivolous poets the doings of baser persons, and as the more serious poets began by composing hymns and encomia, so these began with lampoons....Thus among the early poets, some became poets of heroic verse and others again of iambic verse. Homer was not only the master poet of the serious vein, unique in the general excellence of his imitations and especially in the dramatic quality he imparts to them, but was also the first to give a glimpse of the idea of comedy [in the Margites]...And once tragedy and comedy had made their appearance, those who were drawn to one or the other of the branches of poetry, true to their natural bias, became either comic poets instead of iambic poets, or tragic poets instead of epic poets because the new types were more important-- i.e. got more favorable attention, than the earlier ones. Whether tragedy has, then, fully realized its possible forms or has not yet done so is a question the answer to which both in the abstract and in relation to the audience [or the theater] may be left for another discussion. Its beginnings, certainly, were in improvisation [autoschediastikês], as were also those for comedy, tragedy originating in impromptus by the leaders of dithyrambic choruses, and comedy in those of the leaders of the phallic performances which still remain customary in many cities. Little by little tragedy grew greater as the poets developed whatever they perceived of its emergent form, and after passing through many changes, it came to a stop, being now in possession of its specific nature [tên hautês phusin]. It was Aeschylus who first increased the number of the actors from one to two and reduced the role of the chorus, giving first place to the dialogue. Sophocles [added] the third actor and [introduced] painted scenery. Again, [there was a change] in magnitude; from little plots and ludicrous language (since the change was from the satyr play), tragedy came only late in its development to assume an air of dignity, and its meter changes from the trochaic tetrameter to the iambic trimeter. Indeed, the reason why they used the tetrameter at first was that their form of poetry was satyric [i.e. for "satyrs"] and hence more oriented toward dancing; but as the spoken parts developed, natural instinct discovered the appropriate meter, since of all metrical forms the iambic trimeter is best adapted for speaking. (This is evident, since in talking with one another we very often utter iambic trimeters, but seldom dactylic hexameters, or if we do we depart from the tonality of normal speech. Again, [there was a change] in the number of episodes -- but as for this and the way in which reportedly each of the other improvements came about, let us take it all as said, since to go through the several details would no doubt be a considerable task. (Aristotle: Poetics Chapter 4) Stories about the poet Arion 3. Periander was tyrant of Corinth. The Corinthians say (and the Lesbians agree) that the greatest wonder in his life was the voyage of Arion of Methymna to Taenarum on a dolphin. He was a kitharode second to none at that time and the first of men whom we know to have composed the dithyramb and named it and produced it in Corinth. (Herodotus I.23) 4. Arion, of Methymna...is said also to have invented the tragic mode (tragikoû tropou) and first composed a stationary chorus and sung a dithyramb and named what the chorus sang and introduced satyrs speaking verses. (The Suda lexicon) 5. Pindar says the dithyramb was discovered in Corinth. The inventor of the song Aristotle calls Arion. He first led the circular chorus. (Proculus, Chrest. xii) 6. The first performance of tragedy was introduced by Arion of Methymna, as Solon said in his Elegies. Charon of Lampsacus says that drama was first produced at Athens by Thespis. (John the Deacon, Commentary on Hermogenes) Stories about Cleisthenes, Sicyon, and Hero-drama 7. I must not omit to explain that [the tyrant] Cleisthenes picked on Melanippus as the person to introduce into Sicyon, because he was a bitter enemy of Adrastus, having killed both Mecistes, his brother, and Tydeus his son-in-law. After settling him in his new shrine, he transferred to him the religious honors of sacrifice and festival which had previously been paid to Adrastus. The people of Sicyon had always regarded Adrastus with great reverence, because the country had once belonged to Polybus, his maternal grandfather, who died without an heir and bequeathed the kingdom to him. One of the most important of the tributes paid him was the tragic chorus, or ceremonial dance and song, which the Sicyonians celebrated in his honor; normally, the tragic chorus belongs to the worship of Dionysus; but in Sicyon it was not so -- it was performed in honor of Adrastus, treating his life-story and sufferings. Cleisthenes, however, changed this: he transferred the choruses to Dionysus, and the rest of the ceremonial to Melanippus. (Herodotus V.67) Stories trying to explain why, if tragedy originated from Dithyrambs sung in honor of Dionysus, not all tragedies were about Dionysus ("Nothing to do with Dionysus": (ouden pros ton Dionuson) 8. When Phrynichus and Aeschylus developed tragedy to include mythological plots and disasters, it was said, "What has this to do with Dionysus?" (Plutarch, Symp. Quaest.) 9. Nothing to do with Dionysus. When, the choruses being accustomed from the beginning to sing the dithyramb to Dionysus, later poets abandoned this custom and began to write "Ajaxes" and "Centaurs". Therefore the spectators said in joke, "Nothing to do with Dionysus." For this reason they decided later to introduce satyr-plays as a prelude, in order that they might not seem to be forgetting the god. (Zenobius V.40) 10. Nothing to do with Dionysus. When Epigenes the Sicyonian made a tragedy in honor of Dionysus, they made this comment; hence the proverb. A better explanation: Originally when writing in honor of Dionysus they competed with pieces which were called satyric. Later they changed to the writing of tragedy and gradually turned to plots and stories in which they had no thought for Dionysus. Hence this comment. Chamaeleon writes similarly in his book on Thespis. (The Suda lexicon) Stories about Thespis the Athenian playwright 11. From when Thespis the poet first acted, who produced a play in the city and the prize was a goat... (Marmor Parium, under the year about 534 BC). 12. This is Thespis, who first moulded tragic song, inventing new joys for his villagers, when Bacchus led the wine-smeared (?) chorus, for which a goat was the prize (?) and a basket of Attic figs was a prize too. The young change all this. Length of time will discover many new things. But mine is mine. (Dioscorides, Anth. Pal. VII. 410) 13. The unknown poetry of the tragic Muse Thespis is said to have discovered and to have carried poems on wagons, which they sang and acted, their faces smeared with wine-lees. (Horace, Ars Poetica 275-277) 14. As of old tragedy formerly the chorus by itself performed the whole drama and later Thespis invented a single actor to give the chorus a rest and Aeschylus a second and Sophocles a third, thereby completing tragedy... (Diogenes Laertius III. 56) 15. Thespis: Of the city of Ikarios in Attica, the sixteenth tragic poet after the first tragic poet, Epigenes of Sicyon, but according to some second after Epigenes. Others say he was the first tragic poet. In his first tragedies he anointed his face with white lead, then he shaded his face with purslane in his performance, and after that introduced the use of masks, making them in linen alone. He produced in the 61st Olympiad (536/5-533/2 BC). Mention is made of the following plays: Games of Pelias or Phorbas, Priests, Youths, Pentheus. (The Suda lexicon) 3. The Three Greek Tragedians in the 5th Century 1) Aeschylus (523-456 ca): His are the oldest surviving plays, and he began competing 449 B.C. at the City Dionysia festival. Most of his plays were part of trilogies; the only extant Greek trilogy is The Orestia. He introduced the 2nd actor (Thespis was one, the 2nd added; after 468 B.C. Sophocles is believed to have introduced the 3rd actor, which Aeschylus then used. Characteristics of Aeschylus's plays: o o o o o Characters have limited number of traits, but clear and direct. Emphasizes forces beyond human control. Interested in philosophical issues Power of state eventually replacing personal revenge clash of private revenge and public justices are all reconciled in the end 2) Sophocles (496-406 B.C.): He won 24 contests, never lower than 2nd believed to have introduced the 3rd actor; fixed the chorus at 15 (had been 50) Characteristics of Sophocles' plays: o o o o o o o o o o More emphasis on individual characters reduced role of chorus complex characters, psychologically well-motivated characters subjected to crisis leading to suffering and self-recognition including a higher law above man exposition carefully motivated scenes suspensefully climactic action clear and logical poetry clear and beautiful few elaborate visual effects theme emphasized: the choices of people 3) Euripides (480-406 B.C.): He was very popular in later Greek times, little appreciated during his life sometimes known as "the father of melodrama" Characteristics of Euripides' plays: o o o o o o dealt with subjects usually considered unsuited to the stage which questioned traditional values (Medea loving her stepson, Medea murdering her children) dramatic method often unclear, not always clearly causally related episodes, with many reversals, dues-ex-machina endings many practices were to become popular: using minor myths or severely altered major ones less poetic language, realistic characterizations and dialog Tragedy was abandoned in favor of melodramatic treatment. Theme emphasized: sometimes chance rules world, people are more concerned with morals than gods are. The basic structure of a Greek tragedy After a prologue spoken by one or more characters, the chorus enters, singing and dancing. Scenes then alternate between spoken sections (dialogue between characters, and between characters and chorus) and sung sections (during which the chorus dance). Here are the basic parts of a Greek Tragedy: a. Prologue: Spoken by one or two characters before the chorus appears. The prologue usually gives the mythological background necessary for understanding the events of the play. b. Parodos: This is the song sung by the chorus as it first enters the orchestra and dances. c. First Episode: This is the first of many "episodes", when the characters and chorus talk. d. First Stasimon: At the end of each episode, the other characters usually leave the stage and the chorus dances and sings a stasimon, or choral ode. The ode usually reflects on the things said and done in the episodes, and puts it into some kind of larger mythological framework. For the rest of the play, there is alternation between episodes and stasima, until you reach the final scene. e. Exodos: At the end of play, the chorus exits singing a processional song which usually offers words of wisdom related to the actions and outcome of the play. 1. Satyr Play and Greek Comedy in 5th Century 1) The Satyr Play The Satyr Play, of unknown origin, had to be mastered by tragedians. One satyr play has to be performed if you want to compete in the City Dionysia. o o o o o o Chorus: half-human, half-beast companions of Dionysus sometimes the story is connected with the tragedy it accompanies burlesque of mythology - ridiculing gods or heroes structure similar to tragedy everyday and colloquial language shorter afterpieces to tragedies Examples: The Cyclops - Euripides - from The Odyssey - where Odysseus meets the Cyclops and a captive band of satyrs 2) Greek Comedy not admitted to Dionysus festival till 487-486 B.C. unknown origins or influences perhaps from improvisations of leaders of phallic songs? or from mime: satirical treatment of domestic situations or burlesqued myths six comic dramatists besides Aristophanes (his are the only extant works) Called "Old Comedy" (Menander's plays are considered to be Greek "New Comedy") Direct commentary on contemporary society, politics, literature, and Peloponnesian War. Based on a "happy idea" -> a private peace with a warring power or a sex strike to stop war (Lysistrata) exaggerated, farcical, sensual pleasures. Structure of the Comedy: Part One: Prologue - chorus gives debate or "agon" over merits of the “happy idea.” Parabasis - a choral ode addressing the audience, in which a social or political problem is discussed Part Two: Following scenes show the result of the happy idea final scene (komos) : all reconcile and exit to feast or revelry In 404 B.C., Athens was defeated in the Peloponnesian War, and social and political satire declines. 5. Production / Finance: The first competition for tragedy was added to the City Dionysia in 534, probably as an outgrowth of the dithyramb competition. Playwrights applied to the archon (religious leader) for a chorus, and expense was borne by a choregai, wealthy citizen chosen by the archon as part of civic/religious duty. Choregus paid for training, costuming, etc. (choregus also refers to leader of the chorus.) The State was responsible for theatre buildings, prizes, payments to actors (and perhaps to playwrights). Prizes were awarded jointly to playwrights and choregus. Dramatists themselves probably "directed" the tragic plays, but probably not the comedies. Aeschylus and others in his time acted, trained chorus, wrote music, choreographed, etc. Playwrights called didaskalas (teacher) -- [didactic = teaching]. 6. Actors and Acting: Tragedy: Playwrights originally acted, but by 449 B.C. with the contests for tragic actors, they didn't. Actors were semi-professional, at best. Three-actor rule (that only three actors were in productions) seems fixed by 468, and supported by some evidences, but still questioned by some. Comedy had fewer restrictions Playwrights cast till 449 B.C., with the advent of the contests, then the main actors were chosen by lot and the others by the main actors and the playwright. Actors were paid by the State. Only the leading actors were eligible for competition. Three kinds of delivery: speech, recitative, and song. No facial importance - masks used. Gesture and movement were broadened and simplified. Acting styles Actors usually played more than one role, and men played all the parts A vocal acting must have been declamatory because they had to project appropriate emotional tone, mood, and character to a great number of audience. The stylized acting then is obvious as the masks and choral declamation and dancing are added to this declamatory acting. 7. The chorus 1) Tragedy It was dominant in early tragedies of Aeschylus, it gradually diminishes in number and t by Euripides, it is only loosely related to the action Size: traditionally from 50 to 12 to 15. It’s generally believed to be 15 by the time of Sophocles and Euripides. Later diminished in time. Entered with stately march, sometimes singing or in small groups. Choral passages sung and danced in unison, sometimes divided into two groups. Sometimes exchanged dialog with the main characters, rarely individual speaking (though some say the choregus may have spoken / sung alone). The type of groupings are unknown. 2) Old Comedy The number of chorus were about 24 people, sometimes divided into two. Sometimes they could have both genders as in the case of Lysistrata. They were allowed more varied entrances, groupings, and more active participation as actors. Functions of the chorus 1) An agent: gives advice, asks, takes part 2) Establishes ethical framework, sets up standard by which action will be judged 3) Ideal spectator: it reacts as playwright hopes audience would 4) Sets mood and heightens dramatic effects 5) Adds movement, spectacle, song, and dance 6) Rhythmical function - pauses/paces the action so that the audience can reflect. The chorus was usually made up of amateurs - 11 months training - the most expensive part of the production. 8. Music and Dance Music Most believe music was integral part of the performance, and most dialogue was recitative. o o o o Dance probably accompanied by a single flute, sometimes a lute no one knows who composed the music nor what it sounded like probably resembled oriental quarter tones different modes of music associated with comedy or tragedy Tragedy: called emmeleia (meaning harmony, grace, and dignity) Comedy: less dignified-jumping, spinning, etc. Satyrs: lewd pantomime, etc. 9. Costume and Masks Costumes A standard costume for tragedy must have been a chiton, a sleeved, decorated tunic, fulllength usually, derived from robes of Dionysian priests. Cotharnus is a high boot or soft shoe, perhaps elevated with a thick sole. A short cloak may also have been worn, called a chalmys, or a long one called a himation. Vase painting are our major evidence, but the vases are earlier than the 5th century B.C. and many vase painting show other garments, including nudity. Furthermore, the plays themselves have few references to costumes. So, any reconstructive comment on the costumes is at best a combination of secondary proof and well-guessed speculation. Comic costumes would have been adapted from everyday Greek life. Chiton was made too short to emphasize comic elements. Male characters, not the chorus, wore a phallus. Slaves and old men wore comically exaggerated costume. Women probably wore more everyday costume. In Satyr plays, actors would wear goatskin loincloth with phallus in front and tail in back. Masks The use of masks in ancient greek theater draw their origin from the ancient dionysiac cult. Thespis was the first writer, who used a mask. The members of the chorus wore masks, usually similar to each other but completely different from the leading actors. Because the number of actors varied from one to three, they had to put on different masks, in order to play more roles. The actors were all men. The mask was therefore necessary to let them play the female roles. Some people claim that the masks had one more significance: they added resonance to the voice of an actor so that everyone in the huge ancient theater could hear him (Baldry 1971). But that may not be the case. It’s been said that the perfection of the acoustics in the ancient theater of Epidavros is amazing. Even the audience of the last row can hear a whisper from the orchestra. Greek masks aesthetically are connected with some Asian traditional masks of Noh or Korean mask dance. In all, masks determine the identity of the character, not the actorbearer. In Korea too Miyal Halmi is performed by a male dancer who wears’ old woman’s mask. Even in some Noh play, a mask put on a folded clothing is assumed a perfect character. Usually the masks were made of linen, wood, or leather. A marble or stone face was used as a mould for the mask. Human or animal hair was also used. The eyes were fully drawn but in the place of the pupil of the eye was a small hole so that the actor could see. 10. Stages and Staging Greek tragedies and comedies were always performed in outdoor theaters. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. From the late 6th century BC to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC there was a gradual evolution towards more elaborate theater structures, but the basic layout of the Greek theater remained more or less the same. The completed stone auditorium in the 4th century B.C could accommodate 14,000 to 17,000 persons. The major components of Greek theater are labeled on the diagram above. 1.Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. 2. Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter. 4. Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra, and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage, and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters (such as the Watchman at the beginning of Aeschylus' Agamemnon) could appear on the roof, if needed. 5. Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. The Theatre of Dionysos. No trace has been preserved of the 5th-century theatre which must have been simple in form with a few rows of wooden and stone seats. The preserved ruins belong to the monumental theatre built by Lycourgos. The permanent skene (stage) was then constructed, extending in the width of the orchestra. After its destruction by Sulla in 86 B.C., the theatre and the skene were rebuilt.