File - Sung Huh's E

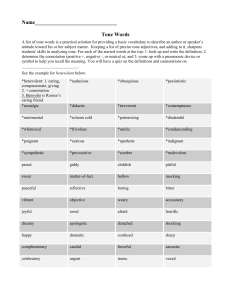

advertisement

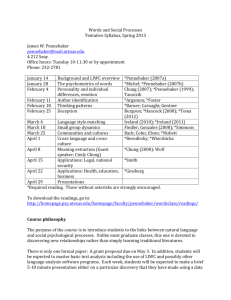

Strategic EAP course (Academic Reading) 6/3-8/7 (every Tuesday and Thursday) Syllabus and Course Schedule instructors Sung Huh email: suh12@psu.edu Course description: This course provides you with the reading skills necessary to be a confident and independent reader, and to help you improve your comprehension of written English in order to compete successfully in an academic program. Course Materials: Textbook is not required. The instructor will provide various outside sources such as newspaper articles, short stories, contemporary essays, academic journal articles, cartoons, and etc. Course Requirements and Assessment: Tradition methods like quizzes, exams, and scoring/grading are not part of the evaluation of this course. Instead, each student will receive individualized feedback and comments from the instructor during and after every task, activity, and performance. Thus, homework, small group work, completion of worksheet, class discussion, presentations and all the participations in class will be carefully monitored to help you. This course requires regular attendance and full participation on students’ part. In addition to the instructor’s constant feedback, a self-assessment method will be frequently built around the course as another activity as to give the ownership of your learning. Week Date What we’ll do in class Assignment 1 6/3 T ice-breakers Self-introduction Introduction to Syllabus questionnaire Write two sentences about the notion of “academic reading” again and compare this with your original sentences that you have written in class.(6/5) 6/5 R introduction to Previewing Skill (scanning and skimming) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6/10 T review with a new text 6/12 R introduction to annotating 6/17 T introduction to outlining and summarizing 6/19 R review with a new text 6/24 T introduction to Comparing, contrasting, synthesizing related readings 6/26 R review with a new text 7/1 T analyzing structures: literature review 7/3 R introduction to plagiarism APA style citation 7/8 T introduction to criticism mitigation Be ready to write a book review in class (7/8)The direction for book review will be provided during the class. Just think about any book that you have read before. Write your reflection on “Petty Crime, Outrageous Punishment: Why the Three-Strikes Law Doesn't Work” (1 page) (7/15) 7/10 R introduction to evaluation an argument 7/15 T review with a new text in-class writing (argumentative writing) Choose an article, or a topic, for the upcoming presentation. Discuss any difficulty with the instructor. 7/17 R introduction to tone/stance Read another chapter of David Sedaris’s book and be prepared to talk about his tone. (7/22) 7/22 T review with a new text 9 10 7/24 R introduction to inference 7/29 T review with a new text presentation demo 7/31 R student presentation 8/5 T student presentation 8/7 R overview 1. Let’s talk about the notion of academic literacy Goals and objectives: Students will be more aware that how important it is to establish a tangible understanding of the concept, academic literacy, particularly academic reading Teacher will provide students with a learning environment in which students foster a sense of ownership for their learning This lesson will remind the fact that all the participants in class benefit from each other by making a contribution to the class Teaching materials: blank posters, markers, tapes, questionnaire sheets, name tags, and syllabus Opening 5 minutes Description Justifications comments Welcome and simple introduction of course and self-introduction of the teacher Name School and Major, or academic interests What makes you unique from others Specific reasons for signing up for this course Teacher’s modeling before a task, whether it is simple or complicated, always assists students’ understandin g of the task. Ice-breaker 10-15 minutes Ask students to introduce themselves in pair and later one student in pairs to represent the other partner to the class based on the conversation beforehand. Talking in small groups first will ease students discomfort with public speech. Activity 1. Write a phrase “Academic reading” on the board. 2. Ask each student to come up with two sentences to define/explain/reflect the notion. 3. Once each student finishes, students are asked to work with their shoulder partner to come up with another two sentences which can embrace the fours sentences. 4. Next, two pairs, four students, gather to discuss and reach an agreed upon conception in two sentences. 5. Each group (four students) writes down their finalized two sentences in a poster and put it up on the board so that everyone can see. 6. As a whole class, discuss an overarching theme from the contents of the posters. This activity will help students externalize the concept of “academic literacy” by orally articulating and negotiating their thoughts with others. 35-40 minutes Presentation 15 minutes Present the crucial components of academic reading and some common issues/challenges that students might face in a real academic discourse community. Introduce the syllabus and give a brief account of reading skills that are going to be taught. Questionnair Have students fill out a questionnaire designed by the instructor. e (Appendix A) 10 minutes The questionnaire will serve to help the teacher in choosing more subjectspecific reading materials. Closing Homework: write two sentences about the notion of “academic reading” again and compare this with your original sentences that you have written in class. Name : Age : Profession : Major/interests you’d like to pursue: The progress of your application process: 1. Have you taken TOEFL and/or GRE? What are the scores? 2. Which schools have you applied? 3. Have you been accepted? If so, when is your departure date? 4. What do you think is the most challenging part in studying abroad? 5. What is your future plan after finishing your study? 6. Do you any experience in staying, traveling, or studying in a foreign country? If you have, please provide some details. 7. Do you have any written work that has influenced on your life? If so, what are they? 8. How would you describe your reading and writing skill? 9. Based on today’s class activity (defining the notion of academic literacy, what aspect of it seems to be most difficult to acquire? 10. What specific challenges do you face when you listen to a lecture in English in general? 11. What specific challenges do you face when you speak in English? (in class) 12. Why are you taking this course? What is your short-term goal with this course? 13. What do you expect from this course? 14. Any question or comment? 2. Rereading strategies: Previewing and Predicting Goals and objective Students will understand the usefulness and significance of pre-reading strategies that involve several of the traditional academic study skills foci. enables students to develop a set of expectations about the scope and aim of the text. to get a sense of the structure and content of a reading selection help students think about what they already know about the topic. The ability to access prior knowledge helps students develop a critical schema (or cognitive map) that they can use to increase their comprehension. To lead students through a series of questions that will help them make an accurate prediction. These predictions help students think about what they already know about the topic. The ability to access prior knowledge helps students develop a critical schema (or cognitive map) that they can use to increase their comprehension. Orientation 10 description What is preview?—analogy to movie preview 1. Present a poster of a movie, “Patch Adams”, which explicitly reveals the famous actor, Robin Williams, the title of the movie and a famous scene of the movie. Ask students in pairs to write their prediction of its genre, its main message, an overarching theme, and story plot. 1. Students watch a video clip, Patch Adams Official justification This will point out that fact that how we use the previewing skill on daily basis for everyday discourse and how it is effective and useful. Trailer - Robin Williams Movie (1998) 2:05 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lZqGA1ldvYE 2. Then, based on what they have watched, students have another chance to revise their prediction about the movie and share their notes with class. 3. Shares the entire, detailed storyline with class. 4. Guide a class discussion on how each pair reaches their conclusion/prediction, what the big clues are, and how bits of information presented work together to construct their final prediction. 5. Lead the discussion into today’s topic of how preview reading skill can help them with purposeful reading. Presentation Discuss ways to enter a text with preliminary impressions 15 and write down students’ input on the board Possible talking points - Titles - Subtitles - Visuals - Headnotes - Abstract - Layout of a text - First and last paragraph - Author - photo captions Questions for students 1. What does the presence of headnotes, an abstract, or other prefatory material tell you? 2. Is the author known to you already? If so, how does his/her reputation influence your perception? If the author is unfamiliar, does an editor supply brief biographical information of the author, an evaluation of the author’s work, or concerns? 3. Is a text broken into parts--subtopics, sections, or the like? Are there long and unbroken blocks of text or smaller paragraphs? What does this arrangement/ layout suggest? How might the parts of a text guide you toward understanding the purpose of a text? 4. Does a text seem to be arranged according to certain conventions of discourse? Think of types of discourse conventions. - Textbooks and journal articles - Blogs - Newspaper - etc. Students often believe they have to start at the beginning and going word by word, stopping to look up every unknown vocabulary item, until they reach the last word for difficult materials. This approach exclusively relies on students’ linguistic knowledge. Through explicit instruction, students have tools and lenses to use for purposeful reading. Activity with a short text, News article 15 1. Students practice the previewing strategy with a newspaper article from The New York Times, “The Power of Pronouns” by BEN ZIMMER. (Appendix )Ask students to read the title and the first two and last two paragraph of the reading and to identity the main idea and purpose of the reading. 2. Pair discussion 3. Class discussion - Whether it is an ample amount of information? - If not, what would help understanding the text without reading it word by word? Which paragraph is worth noting other than the first and last paragraph? Why? Extended Activity with a long text, journal article 20 1. Since they are familiar with employing the previewing skill, teacher presents them with a longer and academic text, two books from liberal art and science field. This time, students will look at the abstract, introduction, contents, some graphic. In the very beginning of the course, since the introduction to an entire book can be intimidating, teacher needs to reassure students by clarifying the purpose of this task. closing The New York Times August 26, 2011 The Power of Pronouns By BEN ZIMMER When President Obama addressed the nation after the killing of Osama bin Laden in May, some conservative reactions to his rhetoric were all too predictable. On -National Review Online, Victor Davis Hanson highlighted the 15 times that Obama used “I,” “me” or “my” in the 1,400word speech, and asserted that “these first-person pronouns . . . reflect a now well-known Obama trait of personalizing the presidency.” A few weeks later, when Obama gave a speech at the C.I.A.’s headquarters in Langley, Va., the Drudge Report offered the headline, “I ME MINE: Obama praises C.I.A. for bin Laden raid — while saying ‘I’ 35 times.” This “well-known Obama trait” has come up again and again in criticisms from the right — George Will has said that Obama is “inordinately fond of the first-person singular pronoun,” while Charles Krauthammer has written of the president’s “spectacularly promiscuous use of the word ‘I.’ ” Regrettably, none of these pundits have bothered to look into how Obama might compare with his predecessors. But this kind of comparative word-counting is right up the alley of James W. Pennebaker, a social psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin. Toward the end of his penetrating new book, “The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say About Us,” Pennebaker crunches the numbers on presidential press conferences since Truman and finds that “Obama has distinguished himself as the lowest I-word user of any of the modern presidents.” If anything, Obama has shown a disdain for the first-person singular during his administration. “Why,” Pennebaker wonders, “do very smart people think just the opposite?” He chalks it up the selective way we process information: “If we think that someone is arrogant, our brains will be searching for evidence to confirm our beliefs.” If we’re predisposed to look for clues that Obama is all about “me me me,” then every “me” he utters takes on outsize importance in our impressionistic view of his speechifying. But even more counterintuitively, Pennebaker argues that Obama isn’t somehow being humble or insecure in his low frequency of first-person pronouns; in fact, his language use reveals him to be quite self--confident. Speakers displaying self--assurance have a lower frequency of I-words, even though most people would assume the opposite. So the knock on Obama may indicate that listeners can properly discern his self-confidence (along with what Pennebaker calls his “emotional distance”) but then attribute this quality to precisely the wrong details of his speaking. Little wonder that Pennebaker’s “primary rule of word counting” is “Don’t trust your instincts.” Mere mortals, as opposed to infallible computers, are woefully bad at keeping track of the ebb and flow of words, especially the tiny, stealthy ones that most interest Pennebaker. Those are the “style” or “function” words, which, along with pronouns, include articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs and conjunctions — all of the connective tissue of language. We’re reasonably good at picking up on “content words”: nouns, action verbs, adjectives and adverbs. But “function words are almost impossible to hear,” Pennebaker warns, “and your stereotypes about how they work may well be wrong.” (Quizzes at Pennebaker’s Web site allow readers to demonstrate just how wrong we usually get things.) The under-the-radar sneakiness of function words actually makes them uniquely suited to Pennebaker’s wide-ranging research goals, which focus on uncovering traces of our social identity and individual psyche in everyday language use. It also helps that these little words make up a vast majority of the most common words in the language, which means that Pennebaker and his colleagues can collect them in large enough numbers to support statistical analysis of a whole variety of texts, from Twitter posts to despairing poetry. Pennebaker admits that word-counting programs are “remarkably stupid,” unable to recognize irony, sarcasm or even the basic contextual clues that allow us to distinguish which meaning of a word is intended. Yet these “stupid” programs have led to a series of unexpected findings ever since Pennebaker first saw the need for one 20 years ago. At the time, he and his graduate students were working through thousands of diary entries written by people suffering from depression, analyzing how people deal with traumatic moments. Writing about trauma seemed to help some people, but why? To answer the question, his team created a program to read the diary entries automatically and count words related to different psychological states, like anger, sadness and more positive emotions. Helped by a grad student sleuth named Sherlock Campbell, Pennebaker looked past the content--related terms to discover that a change in the use of function words, particularly pronouns, was the best indicator of improved mental health. Recovery from trauma seemed to require a kind of “perspective switching” — reflecting on problems from different points of view — that shifts in pronoun use could facilitate. “The Secret Life of Pronouns” outlines in lively and accessible detail how that initial discovery led Pennebaker to appreciate the many ways in which function words reveal our interior lives. He has found strong correlations according to such factors as gender, age and class. For instance, women, younger people and people from lower social classes more frequently use pronouns and auxiliary verbs — words that supposedly signal both lower status and greater social orientation. Lacking power, he argues, requires a deeper engagement with the thoughts of one’s fellow humans. At times, Pennebaker’s post-hoc explanations are disappointingly sketchy. Why do men tend to use more articles than women? Because “guys talk about objects and things more than women do . . . the broken carburetor, the wife, and a steak on the grill for dinner.” Though he admits that’s a “shameless generalization,” it carries a whiff of the unscientific “Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus” school of gender stereotyping. More convincing are cases where Pennebaker and his fellow researchers catch on-the-fly changes in the way people connect with others, from lying to loving. In seeking a bond, people readily accommodate to one another’s manner of speaking through “language style matching,” getting their function words in sync. When an experience is shared, whether it’s building a business relationship, supporting a sports team or commiserating after a tragedy like 9/11, pronouns can mutate, with “I” dropping out in favor of the inclusive “we.” But “we” doesn’t always indicate solidarity: John Kerry’s advisers made that mistake during the 2004 presidential race, Pennebaker says, by trying to get their candidate to use “we” more often. Kerry was already using “we” too much, and to negative effect. “When politicians use them,” Pennebaker writes, “we-words sound cold, rigid and emotionally distant.” So would cutting down on we-words have made Kerry more personable to voters? It’s not that simple. “My language therapy would have been to try to change his relationship with the audience and the way he was thinking about himself,” Pennebaker writes. He compares words to a speedometer: “You can’t slow the car by directly affecting the speedometer.” Paying closer attention to function words, he advises, can help us understand the social relations that those words reflect. Unfortunately, we might not be able to pay proper attention until we’re all equipped with automatic word counters. Until that day, we have Pennebaker as an indefatigable guide to the little words that he boldly calls “keys to the soul.” Evaluating an argument: Fact and Opinion Goals and objectives To help student to begin looking at information with the questioning eye of a critical reader To make students enable to recognize the distinction between fact and opinion in real material which may not as clear as we think To cultivate students’ understand how these two discursive features, fact and opinion, work together to construct one’s argument Teaching material: worksheet, a reading text, access to online Orientation (7-10) description 1. Watch a TV Advertise, Cymbalta Commercial( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crkHJnMx No4), and ask students share their initial reaction to the ad. 2. Ask students to criticize this ad and watch the ad again. Question students if their reactions have been changed. Why? Find linguistic devices, or others that might justify the feelings. 3. Discuss “advertising effects”. Presentatio n (10-15) 1. Present the difference between facts and Opinions by interacting with students. Facts : data that can be proved true through objective evidence or accepted as objectively verifiable - Historical reports - Experimental or scientific observation - Statistical data - Some cause and effect Opinions: a belief, judgment, or conclusion that cannot be objectively proved true - Interpretation of data - Predictions - Judgment 2. Lead a discuss some genres and literacy motivations that cause a blurry line between the two. Think about linguistic justification Students are urged to have a critical eye for ad. This helps them realize how everyday discourse blends fact with opinion. To make the information during the presentation stage, accessible, teacher prepares some exemplar mini texts for each point, but before Pre-reading and reviewing the previously learned reading skills (20-25) Reading activity (20-25) clues and contexts that help separating fact form opinion Talking points: - Facts and opinions often go together. - Once it is a fact, is it always a fact? - Can statements of opinions be disguised as facts? How? - Is widespread belief a fact? - Use of evaluative words? - Use of modal that indicates level of certainty? - Level of expertise of writer - Are the facts presented in an objective manner? - Do the facts actually provide support for the author’s opinions? - Have unfavorable or negative points been left out? Before, students zero in on a new text, “Petty Crime, Outrageous Punishment: Why the Three-Strikes Law Doesn't Work” by Carl M. Cannon(Appendix ), to separate fact from opinion, students practice the previously learned reading skills, previewing and predicting and identifying main idea and summarizing. 1. Who is Carl M. Cannon? 2. What does the title of the essay tell you? 3. Skim the essay and find repeated key words. Then, identify the main idea and predict the writer’s stance. 4. Takes turns to read though the text out loud. 5. Revise the main idea that you have come up with earlier and write a summary in their notebook. 6. (A couple of students) Share your summaries with the class. 7. (The whole class) Discuss your opinions of the criminal justice system in the United States, or in Korea. Have students work together in small groups (3-4 persons) to thoroughly examine the essay to evaluate the argument. Ask them to fill out the worksheet (Appendix ) while referring to the prompts below. To complete the worksheet, students have to provide both a sentence and a supporting linguistic cue. If there is any grey area, students leave a comment for later discussion. Evidence used 1. Is there a clear distinction between fact and opinion? 2. Is evidence used to support arguments? How good is the evidence? Are all the points supported? 3. Are there any unsupported points? Are they well-known facts or generally accepted opinions? 4. How does Carl M. Cannon use other texts and other people's ideas? If not, what kind of other sources can you think of to make a better argument? doing so, teacher elicits students input first. Every class, this is a significant step in which what students have learned in previous classes are practiced in a recurring manner. Becoming a critical reader, students should not take the text in front of them in the way it represents. They should get into a habit of evaluating the 5. Are Carl M. Cannon’s conclusions reasonable in the light of the evidence presented? Extended discussion (10) Closing Assumptions made 1. Are they any assumptions Carl M. Cannon has made? Are they valid? 2. What beliefs or values does Carl M. Cannon hold? Are they explicit? 3. Look for linguistic devices such as emphatic word, hedges, intensifiers and others. The class comes back for a discussion. Have students in turns present their evaluation on the argument and discuss some unclear areas together and how the ambiguity is discursively constructed. truthfulness of text, and find the evidence right from the text. During the previous activity, teacher should monitor students’ performanc e and conduct ongoing assessment to elucidate the grey areas this time. Have students submit their worksheet for further feedback. Homework: Write a page long reflection paper for the essay. Worksheet Fact Linguistic cues/comments By the end of last year, Statistics 2,344 of the 7,574 three-strikers in the C: Maybe factstate’s penal system checking is needed? got their third strike Is it necessary? for a property offense. Opinion A prison term was appropriate Linguistic cue/comments Evaluative adjective: appropriate Fact+opinion: Confusing: October 2005 edition of Reader’s Digest Petty Crime, Outrageous Punishment: Why the Three-Strikes Law Doesn't Work By Carl M. Cannon There was nothing honorable about it, nothing particularly heinous, either, when Leandro Andrade, a 37-year-old Army veteran with three kids and a drug habit, walked into a Kmart store in Ontario, California stuffed five videos into his waistband and tried to leave without paying. Security guards stopped him, but two weeks later, Andrade went to another Kmart and tried to steal four more videos. The police were called, and he was tried and convicted. That was ten years ago, and Leandro Andrade is still behind bars. He figures to be there a lot longer: He came out of the courtroom with a sentence of 50 years to life. If you find that stunningly harsh, you're in good company. The Andrade case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Justice David Souter wrote that the punishment was "grossly disproportionate" to the crime. So why is Andrade still serving a virtual life sentence? For the same reason that, across the country, thousands of others are behind bars serving extraordinarily long terms for a variety of low-level, nonviolent crimes. It's the result of well-intentioned anti-crime laws that have gone terribly wrong. Convinced that too many judges were going easy on violent recidivists, Congress enacted federal "mandatory minimum" sentences two decades ago, mainly targeting drug crimes. Throughout the 1990s, state legislatures and Congress kept upping the ante, passing new mandatory minimums, including "three strikes and you're out" laws. The upshot was a mosaic of sentencing statues that all but eliminated judicial discretion, mercy, or even common sense. Now we are living with the fallout. California came down hard on Andrade because he'd committed a petty theft in 1990 that allowed prosecutors to classify the video thefts as felonies, triggering the three-strikes laws. The videos that Andrade stole were kids' movies, such as Casper and Snow White -- Christmas presents, he said, for nieces and nephews. A pre-sentence report theorized he was swiping the videos to feed a heroin habit. Their retail value: $84.70 for the first batch and $68.84 for the second. When Andrade's case went before the Supreme Court, a bare majority upheld his sentence. But rather than try to defend the three-strikes law, the opinion merely said the court should not function as a super-legislature. Andre will languish in prison, then, serving a much longer sentence for his non-violent crimes than most first offenders, or even second-timers convicted of sexual assault or manslaughter. Politicians saw harsh sentences as one way to satisfy voters fed up with the rising crime rates of the '70s and '80s, and the violence associated with crack cocaine and other drugs. And most would agree that strict sentencing laws have played a key role in lowering the crime rate for violent and property crimes. Last June, Florida Governor Jeb Bush celebrated his state's 13th straight year of declining crime rates, thanks in part to tough sentencing statues he enacted. "If violent habitual offenders are in prison," Bush said, "they're not going to be committing crimes on innocent people." California, in particular, has seen a stark drop in crime since passing its toughest-in-the-nation three-strikes law more than ten years ago. Mike Reynolds, who pushed for the legislation after his 18-year-old daughter was murdered by two career criminals, says that under three-strikes, "those who can get their lives turned around, will. Those who can't have two choices -- leave California or go to prison. The one thing we cannot allow is another victim to be part of their criminal therapy." But putting thousands behind bars comes at a price -- a cool $750 million in California alone. That's the annual cost to the state of incarcerating the nonviolent offenders sentenced under three-strikes. Add up all the years these inmates will serve on average and, according to the Justice Policy Institute, California's taxpayers will eventually shell out more than $6 billion. For a state with a battered economy, that's a pile of money to spend on sweeping up petty crooks. The law also falls hardest on minorities. African Americans are imprisoned under three-strikes at ten times the rate of whites, and Latinos at nearly double the white rate. While crime rates are higher for these minorities than for whites, the incarceration gap is disproportionately wide under three-strikes largely because of drug-related convictions. Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee is blunt when it comes to the three-strikes approach to justice: "It's the dumbest piece of public-policy legislation in a long time. We don't have a massive crime problem; we have a massive drug problem. And you don't treat that by locking drug addicts up. We're putting away people we're mad at, instead of the people we're afraid of." There are some telling figures. In 1985 about 750,000 Americans were incarcerated on a variety of pending charges and convictions in federal and state prisons and local jails. The number of inmates is now about 2.1 million, of which some 440,000 were convicted on drug charges. A significant portion of the rest are there because drug addiction led them to rob and steal. Early on there were signs that mandatory minimum laws -- especially three-strikes statutes -- had gone too far. Just a few months after Washington state passed the nation's first three-strikes law in 1993, a 29-year-old named Paul Rivers was sentenced to life for stealing $337 from an espresso stand. Rivers had pretended he had a gun in his pocket, and the theft came after earlier convictions for second-degree robbery and assault. A prison term was appropriate. But life behind bars, without the possibility of parole? If Rivers had been packing a gun -- and shot the espresso stand owner -- he wouldn't have gotten any more time. Just a few weeks after California's three-strikes law took effect, Brian A. Smith, a 30-year old recovering crack addict, was charged with aiding and abetting two female shoplifters who took bed sheets from Robinsons-May department store in Los Cerritos Shopping Center. Smith got 25 years to life. As a younger man, his first two strikes were for unarmed robbery and for burglarizing an unoccupied residence. Was Brian Smith really the kind of criminal whom California voters had in mind when they approved their three-strikes measure? Proponents sold the measure by saying it would keep murders, rapists and child molesters behind bars where they belong. Instead the law locked Smith away for his petty crime until at least 2020, and probably longer -- at a cost to the state of more than $750,000. His case is not an aberration. By the end of last year, 2,344 of the 7,574 three-strikers in the state's penal system got their third strikes for a property offence. Scott Benscoter struck out after stealing a pair of running shoes, and is serving 25 years to life. His prior offenses were for residential burglaries that, according to the public defender's office, did not involve violence. Gregory Taylor a homeless man in Los Angeles, was trying to jimmy a screen open to get into the kitchen of a church where he had previously been given food. But he had two prior offenses from more than a decade before: one for snatching a purse and the other for attempted robbery without a weapon. He's also serving 25 years to life. One reason the pendulum has swung so far is that politicians love to get behind popular slogans, even if they lead to bad social policy. Few California lawmakers, for example, could resist the "use a gun, go to prison" law, a concept so catchy that it swept the nation, and is now codified in one form or another in many state statues and in federal law. It began as a sensible idea: Make our streets safer by discouraging drug dealers and the like from packing guns during their crimes. But the law needs to be more flexible than some rigid slogan. Ask Monica Clyburn. You can't, really, because she's been in prison these past ten years. Her crime? Well, that's hard to figure out. A Florida welfare mom, Clyburn accompanied her boyfriend to a pawnshop to sell his .22caliber pistol. She provided her ID because her boyfriend didn't bring his own, and the couple got $30 for the gun. But Clyburn had a previous criminal record for minor drug charges, and when federal authorities ran a routine check of the pawnshop's records, they produced a "hit" -- a felon in possession of a firearm. That's automatically 15 years in federal prison, which is exactly what Clyburn got. "I never even held the gun," she noted in an interview from prison. No one is more appalled than H. Jay Stevens, the former federal public defender from the middle district of Florida. "Everybody I've described this case to says, "This can't have happened." [But] it's happening five days a week all over this country." Several years ago, a prominent Congressman, Rep. Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois, was sent to prison on mail-fraud charges. It was only then that he learned what he'd been voting for all those years when anticrime legislation came up and he cast the safe "aye" vote. Rostenkowski told of being stunned at how many young, low-level drug offenders were doing 15- and 20- year stretches in federal prison. "The waste of these lives is a loss to the entire community," Rostenkowski said. "I was swept along by the rhetoric about getting tough on crime. Frankly, I lacked both expertise and perspective on these issues." Former Michigan Governor William G. Milliken signed into law his state's mandatory minimums for drug cases, but after leaving office he lobbied the state legislature to rescind them. "I have since come to realize that the provisions of the law have led to terrible injustices," Milliken wrote in 2002. Soon after, Gov. John Engler signed legislation doing away with most of Michigan's mandatory sentences. On the federal level, judges have been expressing their anger with Congress for preventing them from exercising discretion and mercy. U.S. District Court Judge John S. Martin, Jr., appointed by the first President Bush, announced his retirement from the bench rather than remain part of "a sentencing system that is unnecessarily cruel and rigid." While the U.S. Supreme Court has yet to strike down mandatory minimums, one justice at least has signaled his opposition to them. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy said in a speech to the 2003 American Bar Association meeting that he accepted neither the "necessity" nor the "wisdom" of mandatory minimums. "One day in prison is longer than almost any day you and I have had to endure," Justice Kennedy told the nation's lawyers. "When the door is locked against the prisoner, we do not think about what is behind it. To be sure, the prisoner must e punished to vindicate the law, to acknowledge the suffering of the victim, and to deter future crimes. Still, the prisoner is a person. Still, he or she is art of the family of humankind." It is important to read critically. Critical reading requires you to evaluate the arguments in the text. You need to distinguish fact from opinion, and look at arguments given for and against the various claims. This also means being aware of your opinions and assumptions (positive and negative) of the text you are reading so you can evaluate it honestly. Tone and Stance Goals and objectives Students will establish the difference between tone and mood. Students will be able to identify and appreciate the difference in tone that writer can employ. Students will be aware that understanding is an important part of understanding what an author has written. Students will learn how author’s tone is constructed through various linguistic devises. Students will begin to explore contemporary American humor. Teaching materials: worksheet and a reading text“ Me Talk Pretty One Day by Davis Sedaris”, and handouts (tone/attitude words) Orientation 5-7 minutes description 1. Have students listen to an audio clip that humorously exemplifies how voice tone can carry the stance of each speaker. justification The orientation will guide students to think about the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI8RYfweJ8o 2. Ask students read the following two dialogues. Father: “We are going on a vacation.” Son: “That’s great!!!” Father: “We can’t go on vacation this summer.” Son: “Ok. Great! That’s what I expected.” Presentation 20 minutes Pre reading activity 10-15 minutes 3. Make a point that just as a speaker’s voice can project his feelings, a writers’ tone plays the same role. 1. Explain/discuss what an author’s tone is. - Not an action, but an attitude - Explicitly or implicitly expressed 2. Different from mood: tone vs. mood 3. Distribute a handout, a list of commonly used tone words, and goes over some difficult words for meaning making with the class. (Appendix ) 4. Present 3 different excerpts and ask the students to identify the tone and stance of the author of each story. (Appendix ) Prior to tone/stance analysis, students practice the previously learned reading skills, previewing and predicting and identifying main idea and summarizing with a lengthy reading, “ Me Talk Pretty One Day by Davis Sedaris” 1. Who is David Sedaris? (If students have zero knowledge, teacher will present brief background information about his writing career.) Or, watch David Sedaris' BBC Fringe interview https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LilrdfTnRO A 2. What does the title of the essay tell you? 3. Ask students to preview the essay by reading the first and last paragraph and find repeated key words. Then, predict an overarching theme. relationship between tones and feelings and between tones and meaning-making in both spoken language and written language. Articulating many types of tones will reinforces students perceptions of tones in actual reading. David Raymond Sedaris is an American Grammy Award-nominated humorist, comedian, author, and radio contributor. Students may feel unfamiliar with his work and do not find his writing style relevant to academic reading, but the way he perceives the world and human behavior patterns the way he puts them into words will help students to approach the text in a different perspective. Reading in depth: Tone analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. 40 45minutes 5. 6. 7. 8. Closing Have students read the text. Explain challenging vocabulary if needed. Ask students to revise their summary. (connection with the author) Inquire students if they have been in a situation when they could not communicate effectively and how they are able to express their needs/wants. Have students locate five paragraphs in which they have visible reactions and identify what tones are used. Students are urged to be very specific (humorous, sarcastic, ironic, cynical, and more). Then, ask students explain what evidence they have from the passages, respectively, to support their answer by completing a worksheet. (Appendix) Ask students compare their work with their shoulder partner. Lead a class discussion. Among many types of tones, humor, or irony, in a foreign language can be one of the most difficult, especially when they are subtle/implicit or socio-culturally situated. Thus, this activity will help develop students’ linguistic sensitivity to texts on micro level. Homework : read another chapter of David Sedaris’s book Appendix Tone/Attitude Words 1. Absurd: silly, ridiculous 2. accusatory-charging of wrong doing 3. ambivalent: undecided, having mixed emotions, unsure 4. amused: entertained, finding humor, expressed by a smile or laugh 5. apathetic-indifferent due to lack of energy or concern 6. awe-solemn wonder 7. bitter-exhibiting strong animosity as a result of pain or grief 8. cynical-questions the basic sincerity and goodness of people 9. condescension; condescending-a feeling of superiority 10. callous-unfeeling, insensitive to feelings of others 11. compassionate: sympathetic, having feeling for others, showing pity, empathy 12. contemplative-studying, thinking, reflecting on an issue 13. critical-finding fault 14. choleric-hot-tempered, easily angered 15. condescending: patronizing, stooping to the level of one's inferiors 16. contemptuous-showing or feeling that something is worthless or lacks respect 17. caustic-intense use of sarcasm; stinging, biting 18. conventional-lacking spontaneity, originality, and individuality 19. disdainful-scornful 20. didactic-author attempts to educate or instruct the reader 21. derisive-ridiculing, mocking 22. earnest-intense, a sincere state of mind 23. erudite-learned, polished, scholarly 24. fanciful-using the imagination 25. forthright-directly frank without hesitation 26. gloomy-darkness, sadness, rejection 27. haughty-proud and vain to the point of arrogance 28. indignant-marked by anger aroused by injustice 29. intimate-very familiar 30. judgmental-authoritative and often having critical opinions 31. jovial-happy 32. lyrical-expressing a poet’s inner feelings; emotional; full of images; song-like 33. matter-of-fact--accepting of conditions; not fanciful or emotional 34. mocking-treating with contempt or ridicule 35. morose-gloomy, sullen, surly, despondent 36. malicious-purposely hurtful 37. objective-an unbiased view-able to leave personal judgments aside 38. optimistic-hopeful, cheerful 39. obsequious-polite and obedient in order to gain something 40. patronizing-air of condescension 41. pessimistic-seeing the worst side of things; no hope 42. quizzical-odd, eccentric, amusing 43. ribald-offensive in speech or gesture 44. reverent-treating a subject with honor and respect 45. ridiculing-slightly contemptuous banter; making fun of 46. reflective-illustrating innermost thoughts and emotions 47. sarcastic-sneering, caustic 48. sardonic-scornfully and bitterly sarcastic 49. satiric-ridiculing to show weakness in order to make a point, teach 50. sincere-without deceit or pretense; genuine 51. solemn-deeply earnest, tending toward sad reflection 52. sanguineous -optimistic, cheerful 53. whimsical-odd, strange, fantastic; fun Appendix 1. And the trees all died. They were orange trees. I don’t know why they died, they just died. Something wrong with the soil possibly or maybe the stuff we got from the nursery wasn’t the best. We complained about it. So we’ve got thirty kids there, each kid had his or her own little tree to plant and we’ve got these thirty dead trees. All these kids looking at these little brown sticks, it was depressing.”--a short story “The School” by Donald Barthelme 2. In perpetrating a revolution, there are two requirements: someone or something to revolt against and someone to actually show up and do the revolting. Dress is usually casual and both parties may be flexible about time and place, but if either faction fails to attend the whole enterprise likely to come off badly. In the Chinese Revolution of 1650 neither party showed up and the deposit in the hall was forfeited.--Woody Allen 3. There was a steaming mist in all the hollows, and it had roamed in its forlornness up the hill, like an evil spirit, seeking rest and finding none. A clammy and intensely cold mist, it made its slow way through the air in ripples that visibly followed and overspread one another, as the waves of an unwholesome sea might do. It was dense enough to shut out everything from the light of the coach-lamps but these its own workings, and a few yards of road; and the reek of the labouring horses steamed into it, as if they had made it all. - A Tale of Two Cities --by Charles Dickens Appendix paragraph tone What evidence do you elicit from the passage? critical reading: evaluation and mitigation strategies Goals and objectives Students will become more aware of cultural differences in expressing criticism in written work. Students will become more perceptive of author’s evaluative act, particularly negative evaluation. Students will be more sensitive to the use of mitigation strategies in academic discourse. Students will begin to consciously utilize mitigation strategies in their writing. Teaching materials: a journal article, cartoon, and PPT slides Orientatio n 10-15 minutes Presentati on 10-15 minutes description Present a set of reviews of restaurants, movies and music CD.(Appendix ) Discuss the following talking points 1. directness vs indirectness 2. presence of politeness vs. absence of politeness 3. cultural differences in evaluation 4. differences between description and evaluation justification This will connects everyday discourse with academic discourse which will be Teacher leads the discussion into an academic context. consecutively introduced. 1. Explains evaluation, particularly negative evaluation, is a Although the major component of academic discourse, and then introduce terms for common mitigation strategies that are used to tone down mitigation criticism. strategies might be 2. If needed, articulate the meaning of each term. challenging to 3. Encourage students to provide an example that encapsulates students, the each strategy while teacher is providing some exemplar examples sentences from academic contexts and from reviews above. should be very clear to them. 1. Hedging - Modal verbs(would, could, may) - Adverbs(perhaps, somewhat, possibly) - Epistemic verbs (seem, appear) - Imprecise quantifiers(a little, a bit) - Adverbs of frequency(sometimes, occasionally) 2. Personal attribution 3. Interrogative syntax 4. Implication(implicit) 5. Praise-criticism pairs Prereading activity 10 minutes Before zeroing in on a longer text, activate students’ background knowledge on the topic. 1. Have students read the title of the text and predict the content. “Therapeutic and reproductive cloning: a critique” 2. Ask students read topic related cartoon and discuss ethical issues of cloning -advocates -opponents 3. Distribute the journal article and ask students to preview and skim (by reading heading, subheading, introduction, and conclusion) to get the gist of the article. 4. In depth 1. Assign students in pair one subtopic of the journal article reading for intensive reading. 2. Have each pair summarize that portion first and then, mitigation examine the evaluative language use and mitigation stategies strategies. Since each pair is assigned to a relatively shorter text, students need to thoroughly read it. 30-35 3. Ask one volunteer student to come out and write down each minutes summary from each group during the presentations. 4. Have each pair present their observation to the class. 5. Discuss how similarly, or differently, these mitigation strategies can be used. 6. Have students read the integrated summary and ask if there is any missing link. If so, ask them to go back to the text and redo it. Expansio Ask students write a review for any book they have recently read n with (Students have been asked to select one book prior to this lesson), writing by using mitigation strategies. Connecting reading and writing will 10-15 minutes corroborate 1. restaurant review https://www.google.com/#q=restaurant+review&lrd=lrd I've been to a few Texas Roadhouses and this one was the worst. The food is inconsistent (like the ribs are dry) and the quality seems lower than other ones I have been to. I used to like the bread until I learned it has 300 calories a piece without the butter! Also all the food contains MSG which is a big turnoff. The managers there are especially rude and seem to hate interacting with the guest. When I was there, I witnessed one yell at a guest, and seemed annoyed with everyone there. This location has bad management and ok food. I am not going back 2. movie review http://themovieblog.com/2014/disappointing-raid-2-box-office-hindersmultiplex-indie-expansion/ During opening weekend, THE RAID 2 opened to lukewarm, if not bad, box office numbers. Playing in over 950 locations, the movie opened around $1 million. A high quality subtitled movie playing in so many theaters is great for the consumer, but bad for business…I don’t understand the logic behind Sony Pictures Classics platform release strategy. This happens often. I am surprised that in my grandparent’s small to medium size town of Wichita Falls, Texas that most of SPC films screen there. I doubt there is a demand but it is a valiant effort. As with the first RAID movie which performed almost identical business, there wasn’t demand for a wide release. No pre-release buzz or eager audiences could justify the massive expansion. The same studio did the same thing with the first one (which was my first post for TMB) as well as other movies from CARNAGE to BEFORE MIDNIGHT. There is a reason VOD is a popular format because niche audiences can easily access the material. 3. cd review (BBC Music Magazine, Feb/2014) Before she signed up with Decca, Valentina Lisitsa’s success in promoting her piano playing globally through the visual medium of You Tube had sceptics implying that she couldn’t, surely, be as good as she looked. Her intriguingly programmed Liszt recital should put those doubts to rest. The EL contrabandista operetta fantasy is a serious rarity, and no wonder, as it’s fiendishly hard to play. Lisitsa is more than up to the challenge: in the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12, besides her power and remarkable accuracy, she conjures a Lisztian sparkle and crystalline clarity that sound exactly right. In the transcriptions she finds beautiful colors and line (you won’t hear Schubert’s Der Muller und der Bach played with more poignancy); and her instinct for searching out wide musical spaces suits the B minor Ballade impressively. The downside is her use of the sustaining pedal. Evidently smitten by the additional, ultra-deep resonating strings on a Bosendorfer Imperial Grand, she opts too often for a liberally pedaled sound in which the notes themselves are clear, but the surrounding echo-chamber effect lacks variety. Less of this, please-everything else is top-flight.