Education Brief for SACBC Administration Board

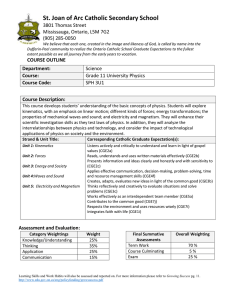

advertisement

Education Brief for SACBC Administration Board 5 May 2015 This brief offers a snapshot of current education issues in South Africa. 1.1 Number of Children in South Africa No. of Children in SA 18.6 million No. in schools Not receiving an education Drop-out rate 12.4 million 6.2 million 56 % live in extreme poverty 11.1 million receive child care grant 7-15 years of age 0-7 years 26% In last 3 years of schooling 1.2 Education Statistics No. of public schools Pupils in public schools Teachers in public schools 24 255 11 923 681 (96%) 392 377 Teacher vacancies No. of independent schools 68 000 (estimate) 1 544 (4 %) Pupils in independent schools Teachers in independent schools 495 388 This figure is disputed as being too low 32 495 1.3 Catholic School Statistics No. of schools No. of Public Schools on Private Property No. of Independent schools No. of teachers No. of other staff No. of boys No. of girls Total no. of learners Catholic Black learners White learners 347 246 101 8 402 2 996 83 484 96 294 179 778 24% 92% 8% As noted above 6.2 million children from 0-7 are not in school. A statistic which we do not have is the number of Early Learning Centres in parishes. This is an important part of the education mission of the Church and needs research: Are these merely crèches or are children receiving adequate stimulation and skills? How safe are these centres? Are the children safe from physical harm both in terms of a safe building/ toilets etc and from corporal punishment? 1 Do the care-givers have any early childhood development training? To conduct a survey would require a fairly substantial budget. While the Catholic sector is small there is no other unified group of a similar size. The Catholic sector is also unique in that it embraces both public and independent schools. It is interesting to note the Anglican Church has recently formed an Anglican Board of Education (ABE) with the stated purpose of unifying their schools and opening new schools (in existing buildings) in order to serve those most in need of quality education. At the launch the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town noted that the Catholics had been more successful than they had in maintaining their schools in the face of Bantu education. Independent schools are being touted as the answer to poor state education not only in SA but all over the world. This is largely proposed by neo-liberal economists and for-profit education enterprises. The danger inherent in this approach is that it leads to commodification of schooling and cannot possibly meet the needs of the majority of poor children. 1.4 Education Economics 2015 saw the first austerity budget since 1994. R203.5 billion was allocated to education in 2015 which was a decline from16.79 % of the total budget to 16.69% year on year. In Rand terms education received R1.7 billion less than if the proportions had remained the same as last year. It is important to note that in 2009 the education share was 18% of the budget which means the education budget, while growing above inflation, is actually R18.2 billion lower than it should be if the 2009 levels of commitment had been maintained. 2. Societal Issues While it may seem obvious to say that societal challenges influence schools these challenges have a profound effect, seriously hampering schools’ ability to provide quality education in a safe and conducive climate. Some of these are: Poverty Adolescent HIV Violence Societal Issues Youth Unemployment Teenage pregnancy Child headed households 2 2.1 Poverty Poverty and its consequences are undoubtedly the greatest challenge facing our country. We cannot separate poverty from economic growth. South Africa’s economy has not grown sufficiently to overcome the decades of social and economic discrimination against black South Africans which has left a legacy of income inequality along racial lines. Children are the most vulnerable in the poverty continuum. The following table outlines children living in poverty per province comparing 2003 and 2012 statistics. One can see the positive impact the Child Care Grant has had on children, although the reduction in the three highest provinces, the Eastern Cape, Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal is not as good as it should be. Figure 2a: Children living in income poverty, by province, 2003 & 2012 (“Lower bound” poverty line: Households with monthly per capita income less than R635, in 2012 Rands) 100 Proportion of children (%) 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 EC FS GT KZN LP MP NW NC WC SA 2003 87.0% 2,581,000 77.9% 857,000 51.9% 1,526,000 78.8% 3,344,000 88.8% 2,183,000 78.6% 1,202,000 77.4% 977,000 73.0% 316,000 46.7% 776,000 74.0% 13,760,000 2012 72.4% 1,951,000 55.2% 511,000 33.9% 1,196,000 65.0% 2,648,000 70.8% 1,578,000 62.4% 972,000 59.4% 756,000 53.4% 223,000 27.4% 512,000 55.7% 10,347,000 Source: Statistics South Africa (2003; 2013) General Household Survey 2002; General Household Survey 2012. Pretoria: Stats SA. Analysis by Katharine Hall & Winnie Sambu, Children’s Institute, UCT. Amongst the 18.6 million children, 56% live in households experiencing extreme poverty and 11.1 million receive a child support grant from the state. The existence of small government grants and no fee school policies provide the conditions for 97% attendance in schools. As shown in 1.1 above there are significant problems with the numbers which affects the overall understanding of how many children should be enrolled and how many should complete. Despite government grants and no-fee school policies, the conditions of living in poverty present significant barriers to learning. Importantly most children from poor households will not receive basic early childhood services severely disadvantaging them as compared with children who are prepared for school at age 7. Furthermore 3.3 million children experience hunger and a staggering 69% of children suffer from severe Vitamin A deficiency in the 1-9 age group. With poor nutrition and hunger in extreme cases, children are not able to develop the cognitive or basic motor skills necessary to make the education enterprise successful. 2.2 Child-headed Households A child-headed household is defined as one where all members are under the age of 18 years. In South Africa 0.67% of children live in such households which translates into 122 000 children out of 18.2 million children. In 20 surveys from 2000 -2007 no increase was found in the number of child-headed households which went against predictions that these would dramatically increase. Only 8% of children in child-headed households had lost both parents with 80% having a living mother. Some of these children are living in towns to go to school or whose parent or parents are working away.44% of child-headed households were made up of only one child. 55% being 14 years or older and in 88% of these households at least one child is 15 or older. 90% 3 of child-headed households are in Limpopo, KZN and the Eastern Cape. While it may be hopeful that these did not increase as predicted 122 000 children is still a very large number of extremely vulnerable children. 2.3 Violence Children also experience high levels of trauma related to violence in communities and at school. Despite the abolition of corporal punishment in 1994 in schools, 13.5% of children report cases of corporal punishment. Coupled with high levels of violence in society, in 2014 there were 2.5 million total crimes in South Africa including 2617 cases of serious neglect and ill treatment of children. These statistics are for reported crimes that are successfully investigated and end in courts and are agreed to be lower than the actual level of crime in the country and they paint a picture of an environment where children are likely to have lived in a home that has been burgled, witnessed a violent crime or been victims of a crime. There are virtually no counselling services for children who experience crime that can receive mention. While there are NGOs like Child Line which work on protecting children rights, the lack of counselling services for children means that many socalled lesser crimes and the impact these have on children are not dealt with. It is mandatory for all Catholic schools to adopt a Child Safeguarding Policy and to implement this. Pastoral Care is key to a good Catholic school and schools are assisted to provide good pastoral care in all regions where CIE works. The following graphic illustrates the continuum of violence experienced by children and adolescents: 4 Within schools the most serious challenges are corporal punishment, bullying and abuse. Preventative interventions can include parent formation, ending corporal punishment, implementing and monitoring Child Safeguarding Policies and Procedures as well as offering programmes to schools such as the Building Peaceful Catholic Schools Programme. Education around Gender and Xenophobia is also of critical importance 2.4 HIV and Aids and Teenage Pregnancy While we have seen a reduction in the number of HIV positive people the only group that has increased is the teenage group. Adolescent HIV and 760 000 children born with HIV who are now eligible for anti-retroviral treatment (ARV) continue to make HIV a serious challenge. Children born with HIV who have been on antiretroviral treatment often face major cognitive challenges at school and this challenges the capacity of the state to provide for children with special needs even further. Teenage pregnancy numbers are also a matter of grave concern (26%). Age disparate relationships (where a man is 5 years or more older than the woman) are a major contributing factor as are forced sex and transactional sex – which is described as ‘sex for food’ by some researchers. Schools can address these issues with adequate and positive sexuality education, school feeding, especially for learners on ARVs, genuine free education and teacher support and counseling. The government is currently implementing the Integrated School Health Plan, which includes screening for TB and HIV. A further societal challenge which impacts on both teenage pregnancy and HIV is substance-abuse which is making serious inroads into the life of schools. 5 3. Issues in Schools Curriculum change & lack of resources Teacher competency Alcohol & drug abuse Issues in schools Early Childhood Developemnt Teacher absenteeism Learning difficulties We hear very little positive news of teachers in South Africa. They are labeled lazy, cruel, absent and ignorant. The industrial model of teaching with Union (SADTU) interference at all levels of the system is regarded as a major weakness in South Africa. Appointments are interfered with which is a serious concern for Catholic Public Schools on Private Property. A recently leaked National Education Evaluation and Development Unit report, which had been embargoed by the Department of Basic Education, gave a damning picture of in excess teachers leading to unsustainable teacher salary bills which leaves little or no money for school maintenance. Cronyism is rife, leading to the appointment of subject advisors who have less knowledge and experience than the teachers they are supposed to support. While this may be the case in some areas the number of teachers qualifying is insufficient for future needs. In November 4600 teachers resigned while the aim to have 14000 qualified teachers emerge from universities at the end of 2014 has not materialized. In South Africa schools are classified into Quintiles. Quintiles 1 to 3 are no-fee schools and serve the most needy while quintiles 4 and 5 charge fees. Quintile 5 schools are usually the ex-Model C schools. The gap in educational results between Quintile 5 schools and the rest is highlighted in all tests and the Annual National Assessments. Teachers have faced numerous changes to the curriculum and are suffering from change fatigue. In addition studies demonstrate inadequate subject knowledge and teaching ability. The following table shows the average percentage correct on all 42 items in the Southern and East African Consortium for Monitoring Education Quality ( SACMEQ) 2007 mathematics teacher test by quintile of school socioeconomic status and school location (corrected for guessing) [401 Gr6 maths teachers] 6 In spite of spending proportionally more on education than its neighbours and in relation to other developing countries, South Africa continues to perform poorly. In the SACMEQ reading tests for Grade 6, South Africa’s children performed very poorly. We were in 10th position out of 15 - below Swaziland and Zimbabwe, but above Mozambique and Uganda. And in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Studies (TIMMS) Mathematics, we came 43 of 45 (27 non-rich countries) in Grade 9. We were below Botswana but above Ghana and Honduras. The National School Effectiveness Study followed about 15000 students (266 schools) and tested them in Grade 3 (2007), Grade 4 (2008) and Grade 5 (2009) with the following question. Our government is tracking achievement by the Annual National Assessments (ANAs). This type of testing is highly controversial in the world as teachers then tend to teach only to the test and the wider and richer elements of learning are lost. Our teachers are being closely monitored – they have workbooks and pacesetters to check whether they are at the correct place for the week. Teachers complain that they are forced to move on even when children do not understand or have not grasped the concepts. In the 2014 ANAs the 7 Grade 9 Mathematics results proved shocking with a national average of 10.8%. Only the top 16% of grade 3 students are performing at a Grade 3 level. Language is a major contributor to poor reading. Children are supposed to learn in mother tongue until Grade 3 and then English (and Afrikaans in some schools) becomes the language of teaching and learning. Given that many teachers are not competent in English themselves it is not surprising that children are struggling. The following table expands on causes for non-participation and/or success at school. South Africa tends to measure its system by the National Senior Certificate (Matric) results. 48% of children who began school in 2003 wrote the NSC in 2014 and of these only 36% of these passed. Of the 28% of those who obtained bachelor passes only 15% were from the 30% of schools serving the poorest communities. Catholic schools are beacons of hope when it comes to the NSC results. 4. Unemployed and under-educated young people While South Africa has achieved almost universal school enrollment in primary school, as aimed for in Education for All, this does not translate into children finishing school. Out of 100 children who started school in 2002, 49 did not reach Grade 12, 11 failed Grade 12, 24 passed and 16 achieved a university endorsement. This means that 550 000 dropped out and did not achieve any other form of education, adding to the 50% unemployed and unskilled youth. But what about the young people who dropped out? Unskilled youth and unemployed youth are perhaps the most serious of all problems discussed today. This large drop-out from schools is linked to poor success at school AND a lack of alternate curricula. A 2013 report of the Department of Basic Education showed that nearly 60% of learners leave school with no qualification beyond Grade 9. 8 The following table highlights startling statistics about semi-skilled and low-skilled Black Africans. There were more semi-skilled 15- 34 year olds in 2014 than in 1994. Church skills centres try really hard to make a difference in young peoples’ lives. CIE Thabiso Skills Institute currently serves 27 Skills centres. Seven of these are registered as Public Adult Learning Centres and 12 are accredited with SETAs. The bureaucracy involved in assisting these centres to get courses accredited is frustrating. A White Paper currently in process requires work place experience before young people can receive a qualification. It is very difficult for young people to access work place experience and as a result Thabiso Skills staff are actively lobbying for this to be removed from the Bill. 9 5. Government and Community Relationships Developing sound relationships with both the Basic and Higher Education Departments is essential for our schools, especially with regard to their ‘distinctive Catholic character’. Advocacy has to take place at national and provincial level, with district officials and with school staff and parents. CIE has established a good working relationship with the DBE departments and liaises with other SACBC bodies such as The Catholic Parliamentary Liaison Office and with other education NGOs and associations such as the National Alliance of Independent Schools Associations (NAISA), which meets twice a year with DBE officials. CIE also assists individual school owners with specific problems and local Catholic Schools Offices on request. The implementation of the Deed of Agreement needs constant and consistent advocacy. There is a serious threat to many of our schools through both departmental and school level ignorance and even obstruction. 6. Challenges faced by the Church and Owners The context outlined in this paper begs the question of how is the Church to respond to the crisis. The vast majority of Catholic children attend normal public schools not Catholic schools and there are thousands of Catholic teachers in the state system. What of these children? Is it time for the Church to reimagine and recommit to Catholic schools in South Africa? In 1953 when the Bantu Education Act was passed the Church raised one million pounds to keep Catholic schools going. The Vatican documents on Catholic education are a wonderful source of inspiration as is Africae Munnus. The new document EDUCATING TODAY AND TOMORROW - A Renewing Passion, is to be finalised in November and has much to say about Catholic schools in this time. Schools struggle to find adequately trained Religious Education teachers in both public and independent Catholic schools. While the National Religious Education Department works hard to fulfill its mandate it is becoming increasingly difficult to raise funds to support their work. This seriously constrains a key aspect of Catholic School education. Some further ideas: Reinvest in existing Catholic schools, particularly with regards to maintenance. This will involve continuing to hold provincial department to account as per the Deed of Agreement. Parenting programmes in parishes. Supporting and encouraging the vocation of teachers – affirming and supporting them. Establishing reading clubs in parishes. Homework help from unemployed youth with teacher supervision. In times of challenge it is important to remember our vision and hope. Most of our existing schools are such places with some having visionary and dedicated leaders. Supporting them is for CIE a privilege and an honour. 10 11