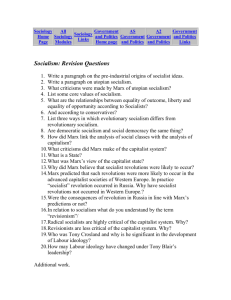

Origins of Socialism

advertisement

The Origins of Socialism Kevin J. Benoy Origins of Socialism • Socialism is not now, nor has it ever been, a single movement. • Socialists may often have similar beliefs, but their political tactics have varied widely. Ancient Origins • Some see the origins of Socialism in Plato’s Republic. • Others see Socialist beliefs in the teachings of Christ and Mohammed. More Recent Origins • Still others look to the ideal of a more equal society in the 16th Century writer Sir Thomas More, author of Utopia. Modern Socialism • Modern Socialism was a reaction to problems faced by society during the early industrial revolution. • Socialists shared the notion that the injustices and inequalities of the modern age should be reduced or eliminated. Modern Socialism • There was huge disagreement on how equality could be achieved: – Some called for a strong centralized state. – Some called for abolition of the state. – Some called for regulation of capitalism. – Some called for the complete abolition of capitalism. Utopian Socialism France, site of the greatest social revolution of the early modern world, was home to many early revolutionaries. Utopian Socialism Henri de Saint Simon (1760-1825) • Saint-Simon saw the past as having been run by churchmen and aristocrats. • The future would be run by technocrats. “The administration of things will replace the government of man.” • He introduced the idea of central planning – to bring about the elimination of waste. Utopian Socialism Francois-Marie Charles Fourier (1772-1837) • Fourier was a mad genius who hated the world of competition and wasteful commerce – which he, a salesman, inhabited. • He wanted to set up communities that would serve as models for a better future society. • Love and passion would bind mankind together. Utopian Socialism Robert Owen (1771-1858) • Owen was a capitalist, but he was appalled at the conditions that other capitalists had their workers live in. • He felt that healthy and happy workers were better for all society. • He built model communities for his Scottish workers. • He encouraged trade unions. • He began the cooperative movement, which encouraged workers to improve their lot by fostering education Radical Socialism Louis-Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881) • Blanqui was an atheist and a revolutionary, who spent half his adult life in jail. • He called his movement communist. • He felt capitalism would be replaced by cooperative associations – but after a revolution. • He wanted a tight, hierarchical, revolutionary organization that would seize power in the name of the working class. • Some argue that Lenin was more “Blanquist” than “Marxist.” Radical Socialism Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) • Proudhon is generally seen as the father of Anarchism. • We wanted to eliminate all institutions, as well as private property – saying “property is theft.” • He allowed the possession of some tools, but all major items would be socialized. • He opposed political parties, saying they became authoritarian. • During the 1870s Anarchism was as popular as Marxism. • It remained strong in Spain until the late 1930s. The Radicals Karl Marx (1818-1883) • By far the most famous socialist of all, Marx based his assumptions on two principles: – Economics determined how all societies evolved. – Societies inevitably evolved toward what he called Communism. Karl Marx - Societies Evolve • Marx felt that any study of history revealed clear stages of development – Primitive Communism: No rulers. The few goods available were shared. Productivity was low. – Slave Based Societies: Classes were antagonistic. Slaves worked without rights. Governments formed. – Feudal Societies: Lords exploited and lived off the work of peasants. More goods were produced than in slave societies. – Capitalist Societies: The Proletariat (workers and small merchants) do most of the work. A small group of capitalists (the Bourgeoisie) profit. As capitalists seek to increase their profits, workers are reduced to poverty and will ultimately fight back. First would come riots and strikes. Later there would come unions and parties, and ultimately, revolution. – Socialism: The revolution would create a “dictatorship of the proletariat, where the workers consolidate power. The state would control the means of production until classes disappeared. The state would have to defend the revolution against the deposed capitalists and neighbouring capitalist states. – Communism: The elimination of class struggle would allow government to disappear. All ownership would be shared in a world of high productivity. All would be equal and all human needs met. Karl Marx • Marx believed in dialectical materialism. – Marx took Hegel’s notion of progress as the product of ideas changing though a dialectic – thesis/antithesis/synthes is. – He added the notion that only material things exist, so the ownership of things and the means of production are what matter in the world. • Religion was, therefore, merely a tool used to keep the lower classes subservient. Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels • Marx was cast out of his native Germany, living as a political exile in Britain. • There he lived and researched, supported by a an idealistic capitalist fellow German, Friedrich Engels – who supported Marx and his family in London. • Together, they wrote the Communist Manifesto. Karl Marx • Marx is buried in London’s Highgate Cemetary Socialism After Marx • Apart from a brief period in Paris in 1871, there was no Socialist government anywhere in the 19th century. • The commune lasted only 3 months before being crushed by the French government, with 300,000 lives lost. • After this there as no model state available for socialists to study. Socialist Fragmentation • In Britain and Australia, non-revolutionary forms of socialism predominated – with the emergence of Labour Parties which sought to work within the existing electoral systems. • Along with intellectuals, Fabian Socialists, they sought gradual change through practical reforms. German Socialism • Marx remained the father of German Socialism – but even here Marxists reinterpreted the old man’s ideas. • Mainstream socialists, led by Karl Kautsky, believed like Marx that there was inevitable progress and history didn’t need a push. • The revolution need not be a violent one. • The German Social Democratic Party became a model for others around the world. • The party was democratic and allowed debate of all issues. German Socialism • Under the leadership of Eduard Bernstein, the party became even less radical. • Bernstein argued that a mixed economy – both capitalist and socialist, was possible. • He cooperated with liberals against Germany’s aristocratic and militarist leaders. Spartacists • When World War I came, it split the SPD. • Radicals, who had been critical of Bernstein and Kautsky, split off to form the Spartacist group, which would later become the KPD – the Communist Party of Germany. • This group was led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. Russian Socialism • Despite the backwardness of Russian society, and possibly because of it, Russia had a long background of socialist activism. • Men like Alexander Herzen argued Russian socialism might skip the stage of capitalism and build socialism on the peasant traditions from the Mir system. Russian Socialism • In the 1860s and 1870s, radical populists lost faith in the possibility of peasant revolt. • Students took to terrorist actions to try to bring down the Tsarist government. • In 1881 Tsar Alexander II was assassinated – but the system did not collapse. Russian Socialism • Georgy Plekhanov brought Marxism to Russia, basing his faith on the growing factory proletariat. • He rejected any notion of Russia being a special case – saying it needed to evolve like any other state. Russian Socialism Vladimir Illich Ulyanov – Lenin (1870-1924) • Lenin continued the Marxist tradition. • To it, he added the Blanquist notion that any revolution needed to be led by a small band of determined, professional revolutionaries, who would propel the masses into action. Bolsheviks and Mensheviks • In 1903, in a meeting held in London, England, Lenin forced a split in the Russian Socialist party. • The names Bolshevik and Menshvik (“large faction” and “small faction”) relate to the sizes of the groups at this meeting. • In Russia the Mensheviks tended to attract the better educated and move skilled workers. • The Bolsheviks attracted less educated elements. Russian Socialism • By 1917, Lenin no longer believed in waiting for the revolution to come. • In the chaos of 1917, as War took Russia to collapse, Lenin determined to give history a push and to seize power. • He argued that a Russian revolution would not be isolated. It would be followed by revolution in the West – certainly in Germany. In Conclusion • Clearly, Socialism has existed in many forms. • They are united only in their aim of creating fair and equal societies. • Some supporters were radical revolutionaries. • Others were moderate reformers. • Often these extremes were as hostile to each other as to other belief systems. Finis