newgodel

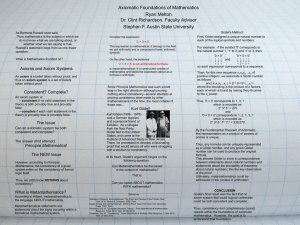

advertisement

Gödel: ‘How did you receive your revolutionary insights?’ Einstein: ‘By raising questions that children are told not to ask’. Gödel raised questions that mathematical logicians and philosophers weren’t supposed to ask. Peirceanly speaking (in order to introduce a variation of Gödel): 1. Generality is that which is accepted as true from the local perspective but possibly true and possibly false from the global perspective. A generality is, then, neither true nor false when considering both perspectives (i.e. it may be ‘falsified’ within some future timespace context). Hence classical logical principles don’t necessarily apply. 2. Particularities that are taken as true from a local perspective are not demonstrably true from the global perspective. Yet within that local perspective they are customarily construed as either true or false (i.e. classical logical principles tend to apply). 3. Possibilities stand a chance of emerging within some future timespace juncture; yet, as possibilities, some will contradict others; nevertheless, both one possibility and another mutually exclusive possibility can coexist as comfortable bedfellow. Hence classical logical principles don’t necessarily apply here either. How can these three apparently unruly misfits be brought together? Don Quixote sees a threatening ‘giant’. Sancho Panza sees a ‘windmill’. Who is right? Both, and neither. They are both right within their local perspective; neither is demonstrably right or wrong within the global perspective. Cervantes’s fictional world is right within its particular perspective. But we can’t simply say it’s wrong when placed within the global, ‘real world’ perspective. In this light, what, then, is the nature of the fiction/‘real world’ distinction with respect to Gödel’s proof? Jaako Hintikka (2000): Gödel numbering is like staging a play. The actors have their normal life outside the play, but they also have a role in the fiction in question. Consequently what they say in the play can be taken in at least two different ways: either as it would be understood in her everyday life, or as a line within the fictive world. Likewise, in Gödel numbering one and the same number string can be taken in two different ways: either as a proposition about numbers in their everyday life as numbers, or as a statement about the formulas that those same numbers represent when they play different characters in their Gödelian play. In both cases we are asked to ‘suspend our belief in the everyday domain’ and ‘suspend our disbelief in the imaginary domain’. We must take numbers or characters to be acting simultaneously in their natural and their artificial roles. In an alternative way of putting this, Zeno’s paradox holds within the local imaginary domain, and as long as we consider Achilles and the Tortoise to be actors within that domain, the Tortoise will always win (we suspended disbelief in the imaginary domain). However, within our own ‘real world’ we know that all we have to do is put the chimerical Achilles in hot pursuit of the Tortoise and it is a no contest (we suspended belief in our everyday domain by including an imaginary situation). Like Zeno’s paradox, Gödel’s sentence says of itself, ‘I am undecidable’, and within that domain there is no decidability; however, we can add another theorem to that domain and thus render it decidable; hence the ‘paradox’, testifying to its ‘inconsistency’, was merely ‘incomplete’, and it was we who imperiously ‘completed’ it; but now, the domain finds itself caught up in the same dilemma anew. Quixote says ‘Giant!’; Sancho says ‘Windmill!’, and within the domain Cervantes offers us there is no solution. However we ‘suspend disbelief’ in the fictive world and give Quixote the benefit of the doubt, or, we place stock in Sancho’s view. Yet, within the fictive domain undecidability ruled. Outside that domain, we would ordinarily opt for Sancho’s reality and Quixote’s dementia; yet, interpreted from another perspective, by ‘suspending our ordinary belief in our levelheaded reason and logic’, we become aware of a little bit of Sancho and a little bit of Quixote in all of us, so the paradox remains. How do we resolve this apparent dilemma? The Gödel sentence is like a statement made by a character in a play about himself and at the same time about real people. Suppose Clint Eastwood says, playing a role in a movie, “In this situation even Clint Eastwood couldn’t keep a straight face”. This statement is part of the movie, not of real life. Yet the meaning and the truth of that statement have to be judged by reference to real persons, in this case Clint Eastwood, the actor. The truth or falsity of the fictivecharacter/real-life-person can only be decided by examining when the actual real-life person would smile in a certain situation, not when the fictive-character in a movie might break out in a grin. Likewise, the Gödelian sentence is a part of a self-referential play, and its truth or provability must be judged as if it were an ordinary arithmetical statement. Peirceanly speaking, once again: 1. A sentence may be considered true within a local perspective (i.e. ‘Atoms are indivisible spheres’), but its truth can’t be absolutely provable. From the global perspective it is neither true nor false, for at some future timespace juncture, there is no knowing which of the range of possible alternate sentences may be considered a more viable candidate (i.e. ‘Atoms are solid indivisible spheres, they are vortices, they are like a solar system, they are a probability amplitude, etc.). 2. A particular sentence, strictly within the norms of a local context, can be considered either true or false, with the stipulation that the sentence may turn out to be either inconsistent or incomplete or both within that local context. 3. The range of pure, unactualized possibilities holds the promise that, however inconsistent and/or incomplete the sentences within a particular context that have been given generality status may be, some alternate sentence will be available for selection at some future timespace context.