Orientalism

advertisement

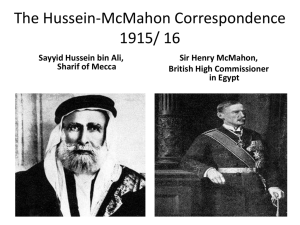

Empire and Aftermath Palestine under the British Mandate Aims • To introduce the history of the British Mandate in Palestine and the parallel histories of Arab nationalism and Zionism. • To consider what life was like in Palestine under the British Mandate, for Arabs, Jews and the British themselves (looking at welfare provision and introducing the concept of ‘Orientalism’). • To think of the British Mandate within the context of imperialism and colonialism to see how the experience compares with other systems you have and will be considering during the module. Part one • The history of the British Mandate, Arab nationalism and Zionism The Ottoman Empire • Until the First World War what became Palestine was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. • During the period of Ottoman rule the term Palestine denoted a geographic region, rather than a specific Ottoman province or administrative district. • The Ottoman Empire was a state founded by Turkish tribes under Osman Bey in 1299. • During the 16th and 17th centuries the Ottoman Empire was one of the most powerful states in the world – a multinational, multilingual empire including much of southeast Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. • The Ottomans were ethnically Turkish and religiously Muslim, but their empire was extremely diverse and included many ethnicities and large Jewish and Christian populations. • Christians and Jews did not have full equal rights, but were usually protected. The Ottoman Empire Arab nationalism • From the 16th through 20th centuries, most Arabs lived in the Ottoman Empire. • Nationalist ideas began to spread to Arabs in the late 19th century. • Arab interest in nationalism began as a literary and cultural movement to re-establish the prominence of Arab culture and to promote a positive ethnic identity. As time passed, Arabs increasingly expressed the desire for greater self-rule. I • Before World War I, few Arabs argued for a completely independent Arab state. • As time passed, Arabs increasingly felt that they should have greater selfrule. • During World War I, many Arabs felt greatly mistreated by the Ottoman government and Arab nationalists popularized the idea of independent Arab rule. Zionism 1 • In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “pogroms” against Jews became common. These were organized government-tolerated or governmentsponsored attacks on Jews in Russia and Eastern Europe. • In Western Europe, ghettoes were abolished and Jews were granted legal equality with Christians but anti-Semitism continued to flourish, they began to look for a new solution. • A watershed moment was in 1894 when a Jewish journalist named Theodor Herzl reported on the trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army. • Herzl concluded that the only solution to antisemitism was to establish a Jewish state. • He organized modern political Zionism, which is a Jewish nationalism dedicated to self-determination for the Jewish people in their ancient homeland, the Land of Israel. Zionism 2 • While Jews had long dreamed of returning to their ancient homeland, most felt that this could not happen until God led them there. • Herzl popularized the idea that Jews could reestablish their homeland as an expression of nationalism rather than strictly on the basis of religious belief. • Jews around the world began donating money to purchase land from Arab and Ottoman landowners. • Eastern European Jews began immigrating to these properties and developing the infrastructure of a modern nation with schools, hospitals, and theaters, as well as agricultural communities. • On the eve of the first wave of Zionist-inspired immigration in 1882, the traditional, religious Jewish community in Palestine numbered about 24,000, or 5 per cent of the population of 500,000. By the conclusion of the second wave in 1914, the number had grown to 85,000. World War One • During 1915-1916, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, convinced Husayn ibn `Ali, the patriarch of the Hashemite family and Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina, to lead an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was aligned with Germany. • McMahon promised that if the Arabs supported Britain in the war, the British government would support the establishment of an independent Arab state under Hashemite rule. • But Britain also tried to enlist Jewish support by promising to create a Jewish national home in Palestine. In 1917, the British Foreign Minister, Lord Arthur Balfour, issued a declaration announcing his government’s support for the establishment of “a Jewish national home in Palestine.” • A third promise, in the form of a secret agreement, was a deal that Britain and France struck between themselves to carve up the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire and divide control of the region. • Therefore at the conclusion of the war, both Jews and Arabs felt betrayed. The British Mandate • After WW1 Ottoman Syria was divided between the British and the French. The region known as Palestine came under the control of the British as a mandate granted by the League of Nations. • Britain had a dual mandate in Palestine: to encourage the formation of a “national home” for the Jews and to protect the “civil and religious rights” of the local Arabs. • With the imposition of the Palestine Mandate, the borders of Palestine were defined for the first time. It included land on both sides of the Jordan River encompassing the present-day countries of Israel and Jordan. • However, Palestine did not remain intact for long, because, in 1921, Britain created an administrative entity called Transjordan as a political division of the Palestine Mandate. • From 1922, with the support of the League of Nations, the eastern part of the Palestine Mandate became the Arab state of Transjordan (across the Jordan)—today known as Jordan. The British Mandate Arab-Jewish relations • In 1920 and 1921, clashes broke out between Arabs and Jews in which roughly equal numbers of both groups were killed. • In 1928, Muslims and Jews in Jerusalem began to clash over their respective communal religious rights at the Wailing Wall / al-Buraq. • On August 15, 1929, members of the Betar youth movement demonstrated and raised a Zionist flag over the Wailing Wall. Fearing that the Noble Sanctuary was in danger, Arabs responded by attacking Jews throughout the country. During the clashes, 64 Jews were killed in Hebron and he Jewish community there ceased to exist. During a week of communal violence, 133 Jews and 115 Arabs were killed and many wounded. • Arab violence against the British reached its peak in the second half of the 1930s. climaxing with the Arab revolt which broke out in April 1936. Jewish-British relations • After crushing the Arab revolt, the British reconsidered their governing policies in an effort to maintain order in an increasingly tense environment and issued a White Paper limiting future Jewish immigration and land purchases. • The Zionists regarded this as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration and a particularly offensive act in light of the desperate situation of the Jews in Europe, who were facing extermination. • Relations worsened with the end of the war. Jewish anti-British violence – carried out by violent fringe groups – intensified. • On 15 February 1947 the British government announced that the problem of Palestine would be handed over to the United Nations. On 29 November, a two-thirds majority of the United Nations General Assembly voted for partition of Palestine; some days later the British Cabinet approved the policy for withdrawal, and set the date of 15 May 1948 for ending the Mandate and evacuating all British forces from the country. Part two • Life under the British Mandate for Arabs, Jews and the British The population of Palestine • According to the 1921 British census a total of 752,048 people lived in Palestine. Of this group, 78.34% were Moslems, 9.5% Christians (making an Arab majority of 87.84%), and 11.4% were Jewish. • The following twenty years saw a rapid increase in the general population. By 1942, it had doubled to 1,620,005 people. • Relatively, the Jewish community increased most, growing to 29.90% by 1942. The Moslem percentage decreased to 61.44% in 1942 and the Christian percentage to 7.85%. • The vast majority of the Arab population were rural with a narrow stratum of urban intellectuals, a disproportionate part of whom were Christians. • The Jewish population was a highly diverse included long-time resident Orthodox Jews, a private, mostly land-owning sector and labour Zionists. The largest immigrant groups in the interwar period came from Poland and Russia, comprising farmers, merchants, artisans and urban professionals, secular Socialists as well as devout believers. The population of Palestine Health and welfare 1 • The period of the Mandate saw a transformation in terms of urbanization, social development and improvements in health and education. • Substantial public health programs, including widespread inoculations, helped bring infectious diseases under control, however these overall trends mask variations amongst the different groups who made up the population. • The institutions managing health and education can be divided into three major groups: the British administration, the missionary bodies (of different religious orientations and geographical provenances) and the Zionists. • Due to the Jewish immigrant's higher degree of education and hospitalization, His Majesty's Government regarded its duty in the matter of welfare as rather different from that for an ordinary colony, not accepting any financial responsibility towards facilitating the establishment of the Jewish national home in Palestine. Health and welfare 2 • While some British sanitation measures benefitted all parts of society, the relatively few British educational and medical institutions were directed at Muslim or Christian Arabs. • The central pillars of the Jewish healthcare system during this period were the Hadassah Medical Organization, founded by the American Zionist women’s organization Hadassah in 1921, and the Workers’ Sick Fund (Kupat Cholim), founded by Jewish agricultural settlers in the early 1910s. Mostly under the direction of these two organizations, a massive effort to educate the Jewish public in health and hygiene had taken place. • While officially all institutions were open to all inhabitants of Palestine, regardless of ethnic and religious background, the hostilities of 1929 ended the potential for health services as a unifying force. Hospital attendance lists reveal that by the 1930s, hospitals were ruled by habits approaching voluntary apartheid. Colonial medicine and ‘Orientalism’ • Health and welfare provision in Palestine can be seen as an example of colonial medicine. • British efforts to deal with the health of the population of Palestine were closely linked to their economic interests. Health was not an end in itself, but rather a prerequisite for colonial development. • However what made the British Mandate period unique was the side-byside coexistence of the British administration, the Zionist bodies with their health organizations, religious-related health institutions, and other international health enterprises, each with its own agenda. • Another complicating factor came within the Zionist welfare movement. The Zionist desire to distance itself from the East produced not only a distinction between Jews and Arabs but also between “Western,” that is, European Jews and “Oriental” Jews, that is those from the Middle East and North Africa. The response of these Zionist medical workers to anti-Jewish orientalism was by setting up traditional Jews as oriental, in contrast to the modern Zionist Jews who were described as Western. The British and ‘Orientalism’ • In his famous book Orientalism Edward Said argued that a long tradition of romanticized images of Asia and the Middle East in Western culture had served as an implicit justification for European and American colonial and imperial ambitions. • Many of the British who came to Palestine came with a pre-formed vision of the Holy Land almost invariably shaped by reading and listening to the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, and influenced by a traditional of scriptural illustration and Orientalist art. • A place of romantic adventures, long and complex history and colourful landscapes, the Middle East was geographically near Europe but unimaginably foreign. • The peoples of the East were assumed to be incapable in their irrationality and technological backwardness of deciding their own best interests, and were therefore to be guided by Britain, gently if possible, firmly if necessary, towards a better future. The British and ‘Orientalism’ The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1854–60) is a painting of a biblical scene by the British artist William Holman Hunt who travelled to the Middle East. The British, the Arabs and the Jews • The British in Palestine were a disparate group, some formed by the public school and Oxbridge imperial tradition, others by churches and missionary culture, still others of humbler social origins in the military or police. There were also British businessmen in Palestine. Most British expatriates socialized exclusively within their community. • The British tended to project upon the Arabs of Palestine expectations and feelings absorbed largely from a romantic tradition of Orientalism. The Palestine Arabs were felt to be attractive by virtue of their physical courage, pride in their traditions, and above all the courtesy and generous hospitality. But the British also displayed a casual contempt and feelings of superiority towards the Arabs. • Jews, whether of Oriental or European origin, seemed to most British observers more threatening and less appealing and in the last days of the Mandate they were often feared and hated by their British rulers. The majority of British officials posted there had no great sympathy for the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine. Part three • The British Mandate, the mandate system and colonialism Colonialism and the mandate system • During the Mandate, Palestine was part of the larger British colonial empire, although mandates were a quite particular form of colonialism. • The mandate system, developed in the aftermath of World War I to manage German colonial holdings and the territories of the Ottoman Empire, was a colonial form that was intimately connected to the idea of the nation-state. • While in practice the mandate system may have felt very similar to other forms of colonialism to the populations subject to them, its distinct form did make a difference. • The language of legitimacy deployed by the mandatories (when it was deployed) was not that of a general ‘civilizing mission,’ but of a civilizing mission specifically connected to the idea of future independent states. The uniqueness of Palestine • Palestine was unique because of its specific ‘dual’ mandate. • Distinguished from other mandates where European powers were supposed to shepherd the native population to independence, in Palestine the British had taken on an additional obligation to promote a Jewish national home. • On the other hand, both the Balfour Declaration and Article 6 of the Mandate Charter included explicit pledges to preserve the rights of Palestine’s indigenous population. • In this way, the British had undertaken what became known as a "dualobligation": to help bring about the establishment of the Jewish national home and to safeguard the rights of the Palestinian Arabs in the process. • A great deal of British policy and practice over the course of the Mandate was comprised of efforts to manage, however imperfectly, these conflicting obligations. At the same time, it was only these conflicts (and the conflict on the ground which resulted from them) that seemed to justify the perpetuation of the Mandate at all.