Air Conditioning

advertisement

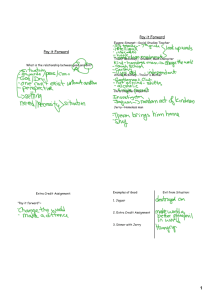

Use e. e. cummings’ “Maggie &millie& molly & may” to answer the following questions. maggie and millie and molly and may went down to the beach (to play one day) and maggie discovered a shell that sang so sweetly she couldn’t remember her troubles,and millie befriended a stranded star who’s rays five languid fingers were; and molly was chased by a horrible thing which raced sideways while blowing bubbles:and may came home with a smooth round stone as small as a world and as large as alone. For whatever we lose (like a you or a me) it’s always ourselves we find in the sea. 1. What literary element is being applied in the title of the poem? a. metaphor b. alliteration c. allusion d. assonance 2. What is the setting of this poem? a. a race track b. the mountains c. the beach d. the moon 3. What is the tone of this poem? a. Sad b. Playful c. Dramatic d. Fearful 4. When “Maggie discovered a shell that sang so sweetly,” what literary element is being used? a. Simile b. Allusion c. Personification d. Onomatopoeia Constructed Response: Which detail from the poem supports the development of the theme? Identify the theme. Use one example from the text to support your answer. Score 0 Score 1 Score 2 No response or the response does not address the prompt Fulfills only 1 of 2 requirements of a level 2 performance Clearly and coherently identifies the theme of the poem; Supports answer with one relevant example from the text Air Conditioning by Malcolm Jones Jr. Few of this century’s major inventions have been so damned and praised, and few have made a greater difference in how and where we live. Frank Lloyd Wright hated it. Las Vegas would not exist without it. It has been credited with everything from lowering the incidence of heart attacks to the rise of the sun belt. It has been blamed for the disappearance of the front porch and the exploding size of the federal government. Few of this century’s inventions have been so damned and praised as air conditioning. The rock band NRBQ once wrote a song called “I Love Air Conditioning,” which included the lyric “And when I’m tired, and I’m so confused/Air conditioning I will use.” There is even a mythology of air conditioning: for years the (unfortunately) baseless tale has circulated that the big character heads— Mickey, Goofy, et al.—at Disney World and Disneyland are airconditioned. Like the car and the television set, air conditioning has always done double duty. It is both an appliance and a social force. People knew they wanted air conditioning long before they were able to produce a machine that could do the job. The early efforts would have made Rube Goldberg blush. The first serious attempt to build an air conditioner in the United States took place in Florida in the 1830s. Dr. John Gorrie created a system that forced air over buckets of ice suspended from the ceiling to lower the temperatures of hospital patients suffering from malaria and yellow fever. Not much progress had been made by the summer of 1881, when President James Garfield lay dying from an assassin’s bullet. Naval engineers contrived a box in which melted ice water saturated flaglike cloths over which a fan blew hot air. This could lower the room temperature by 20 degrees, but in the two months that their machine comforted the dying president, it consumed more than half a million pounds of ice. What we would recognize as an air conditioner—a machine that cools, cleans and dehumidifies air—was not invented until 1902, when a young engineer named Willis Carrier created what he called an Apparatus for Treating Air. Carrier built his machine for the SackettWilhelms Lithographing and Publishing Co. in Brooklyn, N.Y., where humidity was bedeviling printers' efforts to accurately print color. Carrier used chilled coils to cool the air and lower humidity to 55 percent—or to any level desired and precisely every time. This exactness was the most wondrous aspect of the new invention. Carrier’s machine was the template from which all future air conditioners would be struck. Printing plants, textile mills, pharmaceutical manufacturers, the occasional hospital—the first air-conditioned buildings were mostly industrial. (The idea of using Carrier’s invention merely for personal comfort lay decades in the future, although the first air-conditioned home appeared in 1914, when Charles Gates, son of the high-rolling gambler John “Bet a Million” Gates, installed a cooling system in his mansion in—of all places—Minneapolis.) Carrier’s earliest systems were enormous and expensive, as well as dangerous. The original coolant was toxic ammonia. But in 1922 Carrier achieved a double breakthrough, replacing the ammonia with a benign coolant called dielene and introducing a central compressor that made the cooling units much more compact. The biggest step forward came when Carrier sold his invention to the movies, or, more exactly, movie-theater operators. A handful of movie palaces were air-conditioned in the early ‘20s, but the most important debut was at the Rivoli on Broadway in New York City in 1925. Adolph Zukor himself, the head of Paramount Pictures, showed up for the opening. Willis Carrier was there, too, literally sweating it out because when the doors opened to let in the first customers, the system had just been turned on and the building was still hot. “From the wings we watched in dismay as 2,000 fans fluttered.” Carrier wrote of that night. “We felt that Mr. Zukor was watching the people instead of the picture—and saw all those waving fans.” At last cool air began flowing through the air ducts. One by one, the patrons dropped their fans into their laps. “Only a few chronic fanners persisted,” according to Carrier, “but soon they, too, ceased fanning. We had stopped them ‘cold’.” Before long, office buildings, department stores and railroad cars got central air. In 1928 the U.S. House of Representatives got it, followed a year later by the Senate and a year after that by the White House and then the Supreme Court. But the industry’s biggest growth spurt came after World War II. The first window units appeared right after the war, and sales took off immediately, jumping from 74,000 in 1948 to 1,045,000 in 1953. The dripping box jutting out of the bedroom window joined the TV aerial on the roof as instant fixtures in the American suburban landscape. Washington journalists have written endlessly and only halfjokingly about the effects AC has had on D.C., pointing out that the federal bureaucracy mushroomed only after air conditioning appeared on the scene to keep the city’s famously fetid summers at bay. (Federal workers used to be sent home whenever the temperature/humidity index topped 90 degrees.) But sociologists and historians have been largely silent about a much larger change: the rise of the sun belt in precisely the same decades that air conditioning became commonplace south of the Mason-Dixon line. In the 1960s, for the first time since the Civil War, more people moved into the South than left it. In the next decade, twice as many people moved in as departed. The South today is a busier, more crowded, more urban, more industrialized place than it was 50 years ago. It even looks different. Walk down the street of a Southern or Southwestern city at night, and there’s no one out. All you can hear is the sound of the heat pump on the side of the house; all you can see is the blue glow behind the living-room curtains. Where people once wore seersucker and linen, the shoppers of Atlanta and Houston and Phoenix now buy the same clothes people buy in Cleveland or Seattle. With 95 percent of the houses buttoned up for air conditioning, their porches gone, the owners inside all year round, there is no longer any need to accommodate the weather. As Raymond Arsenault, a professor of history at the University of South Florida, points out, “Ask any Southerner over 30 years of age to explain why the South has changed in recent decades, and he may begin with the civil-rights movement or industrialization. But sooner or later he will come around to the subject of air conditioning. For better or worse, the air conditioner has changed the nature of Southern life.” Mostly, Arsenault suggests, by making it less Southern. “General Electric has proved a more devastating invader than General Sherman*,” Arsenault writes. The only thing that allows us to talk about places as different as Miami and Houston and Knoxville and Tucson in the same sentence, the only thing, in fact, that allows us to entertain the notion of something called the sun belt, is that all those places are less unique, blander, if you will, than they were before air conditioning. “The modern shopping mall is the cathedral of airconditioned culture,” says Arsenault, “and it symbolizes the placelessness of the New South.” Perhaps, but it is, at last, a cool place. 1. Which statement best illustrates the author’s argument about the significance of air conditioning? A. Some major inventions become less important in time. B. New inventions are often ignored by the public when they first appear. C. Humans are often reckless in their efforts to control the environment. D. New technology can cause dramatic change in society. 2. How is the author’s position supported by his use of chronological order? A. The development and spread of air conditioning illustrates increasing social changes. B. The increasing difficulty in refining the air conditioner illustrates Carrier’s frustration C. The transition from personal to commercial use of air conditioning illustrates business control of society. D. The political and industrial use of air conditioning illustrates cycles of popularity based on financial trends. 3. What effect is the author most likely trying to achieve in the first paragraph with the repetition of the word it? A. confusion about the conflicting impact of air conditioning B. anticipation for the subject of the article C. mystery about technology whose importance is still unknown D. doubt about the validity of his critics 4. Based on the context of paragraph 5, what does benign mean? A. cheaper B. fragrant C. harmless D. stronger 5. Why was Carrier’s sale of air conditioning to movie theater operators a major step forward in the history of air conditioning? A. It created more widespread awareness and demand for air conditioning. B. It showed how air conditioning could increase business. C. It was the first time air conditioners were used to cool large spaces. D. It allowed movie theaters to thrive in warm and humid climates. 6. According to Washington journalists, what has been the impact of air conditioning on government? A. It has made government more productive by enhancing the working conditions. B. It has decreased efficiency by encouraging more time spent at work. C. It has caused more government offices to open in southern states. D. It allowed government employees to travel to different parts of the country. 7. What is most clearly the effect of Arsenault’s allusion to General Sherman in the last paragraph? A. to caution people about the potential drawbacks of air conditioning B. to compare today’s air conditioned South to the way it was during the Civil War C. to credit air conditioning with conquering the South’s heat and humidity D. to criticize air conditioning for destroying the South’s unique cultural identity CONSTRUCTED RESPONSE: Determine the author’s purpose for starting the selection this way: “Frank Lloyd Wright hated it. Las Vegas would not exist without it. It has been credited with everything from lowering the incidence of heart attacks to the rise of the sun belt. It has been blamed for the disappearance of the front porch and the exploding size of the federal government.” Analyze how the author’s purpose is presented in the entire selection. Include two examples from the text to support your answer. Score 0 - No response or the response does not address the prompt Score 1 - Fulfills only 1 of 4 requirements of a level 4 performance Score 2 - Fulfills 2 of 4 requirements of a level 4 performance Score 3 -Fulfills 3 of 4 requirements of a level 4 performance Score 4 - Clearly and coherently identifies the author’s purpose for starting the selection with the quote; Clearly and coherently analyzes how the author’s purpose is presented in the selection; Supports answer with one relevant example from the text; Supports answer with a second relevant examples from the text. “Darkness at Noon” by Harold Krents Blind from birth, I have never had the opportunity to see myself and have been completely dependent on the image I create in the eye of the observer. To date it has not been narcissistic. There are those who assume that since I can’t see, I obviously also cannot hear. Very often people will converse with me at the top of their lungs, enunciating [each] word very carefully. Conversely, people will also often whisper, assuming that since my eyes don’t work, my ears don’t either. For example, when I go to the airport and ask the ticket agent for assistance to the plane, he or she will invariably pick up the phone, call a ground hostess and whisper: “Hi, Jane, we’ve got a 76 here.” I have concluded that the word “blind” is not used for one of two reasons: Either they fear that if the dread word is spoken, the ticket agent’s retina will immediately detach or they are reluctant to inform me of my condition of which I may not have been previously aware. On the other hand, others know that of [course] I can hear, but believe that I can’t talk. Often, therefore, when my wife and I go out to dinner, a waiter or waitress will ask Kit if “he would like a drink” to which I respond that “indeed he would.” This point was graphically driven home to me while we were in England. I had been given a year’s leave of absence from my Washington Law firm to study for a diploma in law degree at Oxford University. During the year I became ill and was hospitalized. Immediately after admission, I was wheeled down to the X-ray room. Just at the door sat an elderly woman— elderly I would judge from the sound of her voice. “What is his name?” the woman asked the orderly who had been wheeling me “What’s your name?” the orderly repeated to me. “Harold Krents,” I replied. “Harold Krents,” he repeated. “When was he born?” “When were you born?” “November 5, 1944,” I responded. “November 5, 1944,” The orderly intoned. This procedure continued for approximately five minutes at which point even my saint-like- disposition deserted me. “Look” I finally blurted out, “this is absolutely ridiculous. Okay, granted I can’t see, but it’s got to have become pretty clear to both of you that I don’t need an interpreter.” “He says he doesn’t need an interpreter,” the orderly reported to the woman. (16) The toughest misconception of all is the view that because I can’t see, I can’t work. I was turned down by over forty law firms because of my blindness, even though my qualifications included a cum laude degree from Harvard College and a good ranking in my Harvard Law School class. Fortunately, this view of limitation and exclusion is beginning to change. On April 16, the Department of Labor issued regulations that mandate equal-employment opportunities for the handicapped. By and large, the business community’s response to offering employment to the disabled has been enthusiastic. I therefore look forward to the day, with the expectation that it is certain to come, when employers will view their handicapped workers as a little child did me years ago when my family still lived in Scarsdale. I was playing basketball with my father in our backyard according to procedures we had developed. My father would stand beneath the hoop, shout, and I would shoot over his head at the basket attached to our garage. Our next-door neighbor, aged five, wandered over into our yard with a playmate. “He’s blind,” our neighbor whispered to her friend in a voice that could be heard distinctly by Dad and me. Dad shot and missed; I did the same. Dad hit the rim: I missed entirely: Dad shot and missed the garage entirely. “Which one is blind?” whispered back the little friend. I would hope that in the near future when a plant manager is touring the factory with the foreman and comes upon a handicapped and nonhandicapped person working together, his comment after watching them work will be “Which one is disabled?” 1. What is the author’s main purpose for writing this selection? A to describe what it is like to be blind B to correct mistaken ideas about blindness C to prove that blindness is not a handicap D to encourage the blind to live full lives 2. Which word best describes how the author feels when people assume he cannot hear or speak? A. amused B. confused C. frustrated D. Surprised 3. In paragraph 3, what is the author’s purpose in including the following statement about airport ticket agents? “…They fear that if the dread word is spoken, the ticket agent’s retina will immediately detach…” A. to use exaggeration to make his point B. to describe what often causes blindness C. to explain what ticket agents really think D. to impress readers with his use of figurative language 4. Which of the following best brings the author’s experience in the hospital in England alive for the reader? A. first-person narration B. detailed description C. his vivid vocabulary D. his use of dialogue 5. The author most likely included the humorous anecdotes at the beginning of the selection for which of following reasons? A. to entertain the reader with stories of his youth B. to help the reader understand the inappropriate responses people have to others’ disabilities C. to show the reader the injustice of policies that discriminate D. to convince the reader that people with disabilities are no different than people without disabilities 6. According to the author, what is the greatest problem handicapped individuals face? A. poor public facilities for the handicapped B. lack of equal opportunity legislation C. incorrect ideas about the handicapped D. lack of confidence in themselves 7. In paragraph 16, what does the word misconception mean? A. decision B. incorrect idea C. problem D. wrong behavior 8. What effect does the author create by his shift in tone beginning with paragraph 16? A. He draws attention to the serious nature of the problem he has had to learn to live with. B. He makes fun of the people who would not consider him for a job, despite his qualifications. C. He emphasizes the need for federal regulations for employers. D. He contrasts typical responses of others with responses of potential employers. 9. Why did the author include the story from his childhood at the end of the selection? A. to suggest that children can be smarter than many adults B. to encourage blind individuals to get involved in sports C. to reveal how his parents supported and encouraged him D. to show how he wants others to view handicapped people 10. Why does the child ask her playmate, “Which one is blind”? A. She does not understand blindness. B. She has never played basketball. C. She cannot see the faces of the author or his dad. D. She sees no difference in how the author and his dad play. 11. Which word best describes the author’s tone at the end of the selection? A. accepting B. appreciative C. hopeful D. satisfied CONSTRUCTED RESPONSE : Based on the selection, identify the author’s point of view. Explain how the author develops his points. Include one example from the text to support your answer. Score 0 Score 1 Score 2 No response or the response does not address the prompt Fulfills only 1 of 2 requirements of a level 2 performance Clearly and coherently identifies the author’s point of view; supports answer with one relevant example from the text; clearly and coherently explains how the author develops his points. “The Model Millionaire” by Oscar Wilde Unless one is wealthy there is no use in being a charming fellow. Romance is the privilege of the rich, not the profession of the unemployed. The poor should be practical and prosaic. It is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating. These are the great truths of modern life which Hughie Erskine never realised. Poor Hughie! Intellectually, we must admit, he was not of much importance. He never said a brilliant or even an illnatured thing in his life. But then he was wonderfully good-looking, with his crisp brown hair, his clear-cut profile, and his grey eyes. He was as popular with men as he was with women, and he had every accomplishment except that of making money. His father had bequeathed him his cavalry sword, and a History of the Peninsular War in fifteen volumes. Hughie hung the first over his looking-glass, put the second on a shelf between Ruff's Guide and Bailey's Magazine, and lived on two hundred a year that an old aunt allowed him. He had tried everything. He had gone on the Stock Exchange for six months; but what was a butterfly to do among bulls and bears? He had been a tea-merchant for a little longer, but had soon tired of pekoe and souchong. Then he had tried selling dry sherry. That did not answer; the sherry was a little too dry. Ultimately he became nothing, a delightful, ineffectual young man with a perfect profile and no profession. To make matters worse, he was in love. The girl he loved was Laura Merton, the daughter of a retired Colonel who had lost his temper and his digestion in India, and had never found either of them again. Laura adored him, and he was ready to kiss her shoe-strings. They were the handsomest couple in London, and had not a penny-piece between them. The Colonel was very fond of Hughie, but would not hear of any engagement. 'Come to me, my boy, when you have got ten thousand pounds of your own, and we will see about it,' he used to say; and Hughie looked very glum on those days, and had to go to Laura for consolation. One morning, as he was on his way to Holland Park, where the Mertons lived, he dropped in to see a great friend of his, Alan Trevor. Trevor was a painter. Indeed, few people escape that nowadays. But he was also an artist, and artists are rather rare. Personally he was a strange rough fellow, with a freckled face and a red ragged beard. However, when he took up the brush he was a real master, and his pictures were eagerly sought after. He had been very much attracted by Hughie at first, it must be acknowledged, entirely on account of his personal charm. 'The only people a painter should know,' he used to say, 'are people who are bete and beautiful, people who are an artistic pleasure to look at and an intellectual repose to talk to. Men who are dandies and women who are darlings rule the world, at least they should do so.' However, after he got to know Hughie better, he liked him quite as much for his bright buoyant spirits and his generous reckless nature, and had given him the permanent entree to his studio. When Hughie came in he found Trevor putting the finishing touches to a wonderful life-sized picture of a beggar-man. The beggar himself was standing on a raised platform in a corner of the studio. He was a wizened old man, with a face like wrinkled parchment, and a most piteous expression. Over his shoulders was flung a coarse brown cloak, all tears and tatters; his thick boots were patched and cobbled, and with one hand he leant on a rough stick, while with the other he held out his battered hat for alms. 'What an amazing model!' whispered Hughie, as he shook hands with his friend. 'An amazing model?' shouted Trevor at the top of his voice; 'I should think so! Such beggars as he are not to be met with every day. A trouvaille, mort cher; a living Velasquez! My stars! what an etching Rembrandt would have made of him!' 'Poor old chap! said Hughie, 'how miserable he looks! But I suppose, to you painters, his face is his fortune?' 'Certainly,' replied Trevor, 'you don't want a beggar to look happy, do you?' 'How much does a model get for sitting?' asked Hughie, as he found himself a comfortable seat on a divan. 'A shilling an hour.' 'And how much do you get for your picture, Alan?' 'Oh, for this I get two thousand!' 'Pounds?' 'Guineas. Painters, poets, and physicians always get guineas.' 'Well, I think the model should have a percentage,' cried Hughie, laughing; 'they work quite as hard as you do.' 'Nonsense, nonsense! Why, look at the trouble of laying on the paint alone, and standing all day long at one's easel! It's all very well, Hughie, for you to talk, but I assure you that there are moments when Art almost attains to the dignity of manual labour. But you mustn't chatter; I'm very busy. Smoke a cigarette, and keep quiet.' After some time the servant came in, and told Trevor that the frame-maker wanted to speak to him. 'Don't run away, Hughie,' he said, as he went out, 'I will be back in a moment.' The old beggar-man took advantage of Trevor's absence to rest for a moment on a wooden bench that was behind him. He looked so forlorn and wretched that Hughie could not help pitying him, and felt in his pockets to see what money he had. All he could find was a sovereign and some coppers. 'Poor old fellow,' he thought to himself, 'he wants it more than I do, but it means no hansoms for a fortnight;' and he walked across the studio and slipped the sovereign into the beggar's hand. The old man started, and a faint smile flitted across his withered lips. 'Thank you, sir,' he said, 'thank you.' Then Trevor arrived, and Hughie took his leave, blushing a little at what he had done. He spent the day with Laura, got a charming scolding for his extravagance, and had to walk home. That night he strolled into the Palette Club about eleven o'clock, and found Trevor sitting by himself in the smoking-room drinking hock and seltzer. 'Well, Alan, did you get the picture finished all right?' he said, as he lit his cigarette. 'Finished and framed, my boy!' answered Trevor; 'and, by-the-bye, you have made a conquest. That old model you saw is quite devoted to you. I had to tell him all about you - who you are, where you live, what your income is, what prospects you have--' 'My dear Alan,' cried Hughie, 'I shall probably find him waiting for me when I go home. But of course you are only joking. Poor old wretch! I wish I could do something for him. I think it is dreadful that any one should be so miserable. I have got heaps of old clothes at home - do you think he would care for any of them? Why, his rags were falling to bits.' 'But he looks splendid in them,' said Trevor. 'I wouldn't paint him in a frock-coat for anything. What you call rags I call romance. What seems poverty to you is picturesqueness to me. However, I'll tell him of your offer.' 'Alan,' said Hughie seriously, 'you painters are a heartless lot.' 'An artist's heart is his head,' replied Trevor; 'and besides, our business is to realise the world as we see it, not to reform it as we know it. achacun son metier. And now tell me how Laura is. The old model was quite interested in her.' 'You don't mean to say you talked to him about her?' said Hughie. 'Certainly I did. He knows all about the relentless colonel, the lovely Laura, and the £10,000.' 'You told that old beggar all my private affairs?' cried Hughie, looking very red and angry. 'My dear boy,' said Trevor, smiling, 'that old beggar, as you call him, is one of the richest men in Europe. He could buy all London to-morrow without overdrawing his account. He has a house in every capital, dines off gold plate, and can prevent Russia going to war when he chooses.' 'What on earth do you mean?' exclaimed Hughie. 'What I say,' said Trevor. 'The old man you saw today in the studio was Baron Hausberg. He is a great friend of mine, buys all my pictures and that sort of thing, and gave me a commission a month ago to paint him as a beggar. Quevoulez-vous? La fantaisie d'un millionnaire! And I must say he made a magnificent figure in his rags, or perhaps I should say in my rags; they are an old suit I got in Spain.' 'Baron Hausberg!' cried Hughie. 'Good heavens! I gave him a sovereign!' and he sank into an armchair the picture of dismay. 'Gave him a sovereign!' shouted Trevor, and he burst into a roar of laughter. 'My dear boy, you'll never see it again. Son affaire c'estl'argent des autres (his business is other people’s money).’ 'I think you might have told me, Alan,' said Hughie sulkily, 'and not have let me make such a fool of myself.' 'Well, to begin with, Hughie,' said Trevor, 'it never entered my mind that you went about distributing alms in that reckless way. I can understand your kissing a pretty model, but your giving a sovereign to an ugly one - by Jove, no! Besides, the fact is that I really was not at home to-day to any one; and when you came in I didn't know whether Hausberg would like his name mentioned. You know he wasn't in full dress.' 'What a duffer he must think me!' said Hughie. 'Not at all. He was in the highest spirits after you left; kept chuckling to himself and rubbing his old wrinkled hands together. I couldn't make out why he was so interested to know all about you; but I see it all now. He'll invest your sovereign for you, Hughie, pay you the interest every six months, and have a capital story to tell after dinner.' 'I am an unlucky devil,' growled Hughie. 'The best thing I can do is to go to bed; and, my dear Alan, you mustn't tell any one. I shouldn't dare show my face in the Row.' 'Nonsense! It reflects the highest credit on your philanthropic spirit, Hughie. And don't run away. Have another cigarette, and you can talk about Laura as much as you like.' However, Hughie wouldn't stop, but walked home, feeling very unhappy, and leaving Alan Trevor in fits of laughter. The next morning, as he was at breakfast, the servant brought him up a card on which was written, 'Monsieur Gustave Naudin, de la part de M. le Baron Hausberg.' 'I suppose he has come for an apology,' said Hughie to himself; and he told the servant to show the visitor up. An old gentleman with gold spectacles and grey hair came into the room, and said, in a slight French accent, 'Have I the honour of addressing Monsieur Erskine?' Hughie bowed. 'I have come from Baron Hausberg,' he continued. 'The Baron--' 'I beg, sir, that you will offer him my sincerest apologies,' stammered Hughie. 'The Baron,' said the old gentleman, with a smile, 'has commissioned me to bring you this letter;' and he extended a sealed envelope. On the outside was written, 'A wedding present to Hugh Erskine and Laura Merton, from an old beggar,' and inside was a cheque for £10,000. When they were married Alan Trevor was the bestman, and the Baron made a speech at the weddingbreakfast. 'Millionaire models,' remarked Alan, 'are rare enough; but, by Jove, model millionaires are rarer still!' 1. Which quote from the selection best expresses the character of Hughie? a. 'I think you might have told me, Alan,' said Hughie sulkily, 'and not have let me make such a fool of myself.' b. 'Well, Alan, did you get the picture finished all right?' [Hughie] said, as he lit his cigarette. c. 'Well, I think the model should have a percentage,' cried Hughie, laughing; 'they work quite as hard as you do.' d. 'You don't mean to say you talked to him about her?' said Hughie. 2. Why did the millionaire Baron Hausberg give Hughie precisely £10,000? a. It was all he could spare on short notice. b. It was the amount Colonel Merton required that Hughie obtain in order to marry Laura. c. It was the amount Trevor paid the Baron for posing as his model. d. Because “painters, poets, and physicians always get guineas.” 3. What is the point of view of this story? a. Third person-limited b. Third person-omniscient c. First person d. Second person 4. What is the author’s purpose in writing this story? a. To inform readers about the benevolence of wealthy people b. To teach others about the importance of generosity, no matter how rich or poor one is c. To explain the situational irony of a rich person posing as a beggar d. To convince others that art and business are the only ways one can get rich 5. What is the best reason why the author pointed out Hughie’s wedding reception was breakfast in the penultimate paragraph? a. Breakfast is the most important meal of the day. b. Even though Hughie received £10,000, he did not become wasteful in spending money on a lavish dinner reception. c. Baron Hausberg could not attend a dinner reception. d. All social classes were represented at the function. 6. What is the significance of the story’s final line: 'Millionaire models,' remarked Alan, 'are rare enough; but, by Jove, model millionaires are rarer still!' a. To illustrate a play on words b. To point out that a rich person posing as a beggar was unusual, but even more unusual was how he also served as a role model by giving away his money c. To demonstrate the author’s mastery of alliteration d. To show how rare it is for a model to be a millionaire. CONSTRUCTED RESPONSE: Based on the sentence below from the first paragraph, how does the author’s choice of words impact the meaning of the text? Include one example from the text to support your answer. “Ultimately he became nothing, a delightful, ineffectual young man with a perfect profile and no profession.” No response or the response does not address the prompt Score 0 Fulfills only 1 of 2 requirements of a level 2 performance Score 1 Clearly and coherently identifies how the author’s choice of words Score 2 impacts the meaning of the text; Supports answer with one relevant example from the text