Money, Interest Rates, and Exchange Rates

advertisement

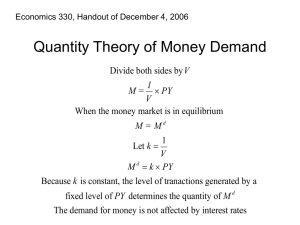

Ch. 15: Money, Interest Rates, and Exchange Rates Udayan Roy ECO41 International Economics What is Money? • Money is any asset that is widely used and accepted as a means of payment. • So, a country’s quantity of money (Ms) includes – All currency with the public and – All checkable deposits • bank deposits in a foreign currency are excluded from this definition. – M1 and M2 are two well-known periodically published measures of the quantity of money Properties of Money: No Return • We can classify all assets into: – Money, which earns no return • Currency with the public plus checking accounts – Assets that earn a return • Stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. Properties of Money: Liquid • Money is very liquid: – that is, it can easily and quickly be used to purchase goods and services. • Assets that earn a return are less liquid than money • So, when deciding how much of their wealth to keep in the form of money, people face a trade off between the convenience of liquid assets and the higher return from less-liquid assets Money Supply • The quantity of money is also called the money supply • Who controls the money supply? • Central banks determine the money supply. – In the US, the central bank is the Federal Reserve. – The Federal Reserve directly regulates the amount of currency in circulation. – It indirectly controls the amount of checkable deposits issued by private banks. Money Demand • Money demand is the amount of their wealth that people are willing to hold in the form of money … – (… instead of other assets that are less liquid but earn a higher return). Money Demand: Individual 1. Interest rate (on interest-earning assets): this is the cost (or, downside) of holding money. 2. Risk: the risk of holding money principally comes from unexpected inflation, thereby unexpectedly reducing the purchasing power of money. – but many other assets have this risk too, so this risk is not very important in money demand 3. Liquidity: A need for greater liquidity occurs when either the price of transactions increases or the quantity of goods bought in transactions increases. Money Demand: Aggregate • Interest rate • Average level of prices • Income Money Demand: Aggregate • Money pays little or no interest. • So, the interest rate on interest-earning assets (such as bonds) is the opportunity cost of holding money (instead of non-money assets). • A higher interest rate means a higher opportunity cost of holding money lower money demand • Therefore, aggregate money demand (Md) is inversely related to the interest rate (R) Money Demand: Aggregate • The overall level of prices of goods and services bought in transactions will influence the willingness to hold money to conduct those transactions. • A higher overall price level means a greater need for liquidity to buy the same amount of goods and services higher money demand • Therefore, aggregate money demand (Md) is directly related to the overall level of prices (P) Money Demand: Aggregate • Higher income implies more goods and services are being produced and bought • So, more money would be needed to conduct transactions. • A higher real national income (GNP) means more goods and services are being produced and bought in transactions, increasing the need for liquidity higher money demand • Therefore, aggregate money demand (Md) is directly related to GNP (Y) Money Demand: Aggregate • 𝑀𝑑 = 𝑃 × 𝐿 𝑅, 𝑌 – here blue indicates a direct effect and red indicates an inverse effect Money Demand: Aggregate • Let’s be specific about the L in money demand • Let 𝐿 𝑅, 𝑌 = 𝐿0 ∙𝑌 𝑅 – here L0 represents all factors—other than P, R, and Y—that affect people’s willingness to hold their wealth in the form of money. 𝑑 • Then, 𝑀 = 𝑃∙𝐿0 ∙𝑌 𝑅 Equilibrium • For an economy to be in equilibrium, money supply must equal money demand • A central bank may determine the money supply • But it cannot force people to hold exactly that much of their wealth in the form of money • Therefore, 𝑀𝑑 = 𝑀 𝑠 is necessary for equilibrium Equilibrium • Therefore, 𝑴𝒔 = 𝑴𝒅 = 𝑷 ∙ 𝑳 𝑹, 𝒀 is essential for equilibrium • With our simplified form of L, the equilibrium 𝑷∙𝑳𝟎 ∙𝒀 𝒔 condition becomes 𝑴 = 𝑹 • This equation has – two parameters—Ms and L0—with values that are assumed known, and – three variables—P, Y, and R—of unknown value This topic is actually in Chapter 17. But let’s do it now anyway. THE AA CURVE Two Markets: Foreign Exchange and Money • So far, we have seen the equilibrium conditions for the two asset markets – The foreign exchange market (Ch. 14), and – The money market (this chapter) 𝒆 𝑬 𝑹 = 𝑹∗ + −𝟏 𝑬 𝑷 ∙ 𝑳𝟎 ∙ 𝒀 𝑴 = 𝑹 𝒔 Equilibrium in Asset Markets • We have simplified the money market 𝑃∙𝐿0 ∙𝑌 𝑠 equilibrium equation to 𝑀 = 𝑅 • Equivalently, 𝑌 = 𝑀𝑠 𝐿0 ∙𝑃 ∙𝑅 • The interest parity equation then yields 𝑌 = 𝑀𝑠 𝐿0 ∙𝑃 ∙ 𝑅∗ + 𝐸𝑒 𝐸 −1 • This equation—the AA equation—must be true if there is equilibrium in the foreign exchange and money markets Equilibrium in Asset Markets • AA equation: 𝑌 = 𝑀𝑠 𝐿0 ∙𝑃 ∗ ∙ 𝑅 + 𝐸𝑒 𝐸 −1 • If all parameters and all variables except Y and E are constant, then we get an inverse link between Y and E. • Why? If E increases, the right-hand-side of the equation decreases. Therefore, Y must decrease. This gives us the AA Curve of Chapter 17. Fig. 17-7: The AA Curve 𝑒 𝑀𝑠 𝐸 𝑌= ∙ 𝑅∗ + −1 𝐿0 ∙ 𝑃 𝐸 Shifting the AA Curve • 𝑌= 𝑀𝑠 𝐿0 ∙𝑃 ∙ 𝑅∗ + 𝐸𝑒 𝐸 −1 – Suppose the economy is initially at Point 2 – Suppose there is a decrease in Ms or R* or Ee, or an increase in L0 or P – If E stays unchanged at E2, then Y must decrease – The economy must go from Point 2 to, perhaps, Point 3 – In other words, a decrease in Ms or R* or Ee, or an increase in L0 or P shifts the AA curve left 3 AA2 Shifting the AA Curve • The AA curve shifts right if: – – – – – Ms increases 𝑒 𝑀𝑠 𝐸 ∗+ 𝑌 = ∙ 𝑅 −1 P decreases 𝐿0 ∙ 𝑃 𝐸 Ee increases R* increases L decreases for some unknown reason (L0↓) E E0 E1 Y0 Y1 Y