Version

advertisement

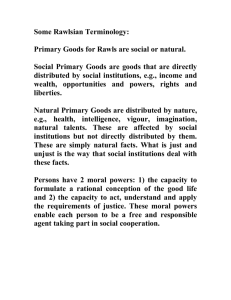

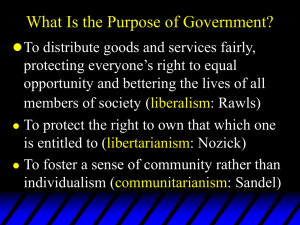

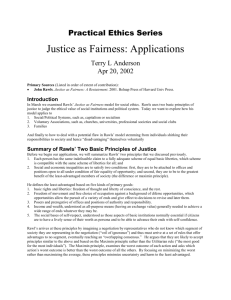

Rawls IV: Wrapping-up PHIL 2345 Original position, cont. of discussion Exclusion of prejudices while contracting in the OP: 'One excludes the knowledge of those contingencies which sets men at odds and allows them to be guided by their prejudices' (TJ, p. 19). Convincing? E.g. if you are a religious fundamentalist? Convinced that some races are superior/inferior to others? Would you suspend this view if you believe it to be a fact? Key points from last lecture Ahistorical account of human rights Principles 1 & 2 Definition of injustice: ‘absolute weight’ for P1 liberties ‘inequalities that are not to the benefit of all’ (62); So inequality as such is not unjust (P2). Rejects trade-off b/w liberties (P1) and economic gains (P2) E.g. economic development prioritsed over personal freedoms, e.g. right to free assembly; Slavery would be ultimate version of this trade-off. Readings on human rights Micheline R. Ishay, ed., The human rights reader : major political essays, speeches, and documents from ancient times to the present, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2007. E-book available. Intro to Question re: 2 P’s Rawls's two principles of justice are derived from a more general conception of justice, i.e., all social values should be distributed equally unless the unequal distribution is beneficial to everyone. Among all social values, Rawls distinguishes between basic liberties on the one hand, and all other values like wealth and income on the other hand. Rawls then defines his two principles in such a way that the first principle--which protects an equal distribution of basic liberties-should always be satisfied before the second principle which ensures any unequal distribution be beneficial to all-- is satisfied. In other words, basic liberties of citizen are always equally distributed, and any unequal distribution of basic liberties is not granted even if it is beneficial to all citizens. I In Rawls's view, basic liberties – e.g., political liberty, freedom of speech, freedom of thought, right to hold property etc.--are given an "absolute weight" with respect to all other social values. Question Rawls believes it is reasonable for us not to exchange our liberties for any social and economic advantages whatsoever. My question is, why should we give liberties such an "absolute weight"? Is it due to our intuition? Indeed, protection of these liberties conforms to our intuition, but how can we ensure that our intuition is correct? Questions re democratic equality "A scheme is unjust when the higher expectations, one or more them, are excessive. If these expectations were decreased, the situation of the least favored would be improved. How unjust an arrangement is depends on how excessive the higher expectations are and to what extent they depend upon the violation of the other principles of justice” (TJ, 79). Expectation cannot easily to be measured in this case; how can we know if/that it is a higher expectation. Also, who will decide whether the expectation is excessive or not? The meaning of excessive expectation is different for the well off versus the others. In this case, there is a possibility that the well-off may think the others have excessive expectations. Question re: most just economic system What kind of economic regime is more compatible with Rawlsian justice, private ownership or social ownership of the means of production? I.e., which works better in achieving the justice goals set by Rawls's principles? Intro to Q. re: human nature and acting justly According to Rawls, most traditional doctrines hold that as a matter of degree, human nature requires people to act justly when we have lived under, and benefited from, just institutions. To the extent that this is true, Rawls said that a conception of justice is psychologically suited to human inclinations. And this conception of justice is justice as fairness as argued by Rawls. But I am not sure why it is the case. Cites case from M.B.E Smith: Acting justly, cont. We can generalize that considerations of fairness show that when cooperation is perfect and when each member has benefitted from the submission of every other, each member of an enterprise has an obligation to obey its rules when obedience benefits some other member or when disobedience harms the enterprise. If a member disobeys, he is unfair to at least one other member or maybe all the members. However, if a member disobeys when his obedience would be beneficial to no other member and when his disobedience does not harm, his moral situation is surely different. If his disobedience is unfair, then it must be unfair to the group, but not to any particular member. According to Smith, this is impossible because despite the fact that the moral properties of a group are not always a simple function of the moral properties of its members, it is evident that one cannot be unfair to a group without being unfair to its members. From this, we see that even in a perfectly cooperative enterprise, considerations of fairness do not establish that members of such enterprise have acted justly to one another. So, does Rawls’s position still hold? Next week: No lectures Please come during your designated time slot for small-group essay tutorials. Sign-up sheet circulated; final schedule to be posted on Google group. Thanks!