Discussion of Nordhaus on Alchemy and the New Economy

Discussion of Nordhaus on

Alchemy and the New

Economy

Robert J. Gordon

Northwestern University and NBER

CRIW, Cambridge MA, July 30, 2002

The Long Tradition Continues

Grad School Office-Mates in 1966-67

I have been pilloried many times by incisive WDN discussant comments

“Darwinian t-statistics”

More varieties in supermarkets? It’s all honey/apple/cinnamon Cheerios (he reads out the brand names . . .)

What is this Paper About?

Are fruits of innovation appropriated by inventors?

Were new economy innovations appropriated more or less than usual?

Empirical measure of appropriability is the behavior of various concepts of the profit share

What Should We Expect ex-ante?

Case 1: Steady stream of innovations

RR => electricity => auto => radio/TV

New economy just more of the same

Profit Share?

Would be constant

Would be higher, the more of the steady stream of innovations are appropriated

But we would have no way of identifying the appropriability share

Uneven Stream of Innovations

Industrial Revolution #1

Steam engine, cotton gin, RR, steam/steel ships

Industrial Revolution #2

Electric motor, electric light, motor transport, air transport

Hiatus: 1970’s, 1980’s

New Economy: IR #3?

When Innovations are unevenly timed

If no appropriability, no effect on profit share

With appropriability, profit share will be positively correlated with pace of innovation

Using MFP growth as a proxy for pace of innovation, profit share would be correlated with

MFP growth

That’s what his model says, and it is a correct and interesting implication

What We Already Know

Labor’s Share, i.e., Profit Share Constant for a

Century, with one exception

One-time-only jump in LS in late 1960s

Consistent with Steady Innovation

Was the jump in LS in late 1960s a marker of a decline in innovation?

How could New Economy (IR#3?) have been appropriated when we know in advance that LS did not decline?

While the question is intriguing, we know the answer in advance from the macro data on LS

What New Economy Skeptics

Already Knew

New Economy a Pipsqueak compared to the

“Great Inventions” (electricity + internal combustion engine)

Much New Economy Innovation was a substitute for other activities

Surfing the web vs. TV

E-commerce vs. mail-order catalogues (Land’s End rules!)

Sears buys Land’s End? The Chicago hinterland rules!

Brutal competition competed away any profits, gains went to consumer

Key steps to understanding paper

Figure 1

Innovation cuts C

0 to C

1

With no Schumpeterian profits, P declines fully

With Schumpeterian profits, P falls partially

Dynamic implications

Without S profits, P and C decline at same rate after the initial period

With S profits, P declines at (1-a) the rate of change of C , profit share in economy approaches a

Example with no decay (λ = 0)

Cost declines at 10 percent per period, assume a = 0.5 as in Figure 1

Cost 100, 90.5, 81.9, . . . , ~0

Price 100, 95.2, 90.9, . . . , 50

Profit 0, 4.8, 9.1, . . . , 50

Notice in equations (4) and (6), the profit share in equilibrium = a when λ = 0

Thus the decay factor (λ) is critical

Radical sensitivity of profit share to λ decay rate, equation (6), assume

h* = .02

With λ successively = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3

Profit share (goes from a to 0.25a

to 0.11a

to .07a

In my example based on a=0.5

and with λ =

0.2 rather than 0.0, profits reduced from 50 to

5.5

With a more plausible a=0.1, from 5 to 0.5

Conclusion: to get a realistic profit share, we need some combination of a low a and high λ

The paper’s main results depend on the choice of λ

Theory: only example considered is λ =

0.2

Example on pp. 15-16

Empirical results in Tables 1 and 3

Since decay = 0.2 implies Schumpeterian profit share is trivial, the paper’s results are largely true by assumption

What about the dynamic results in Tables 2 and 4?

Tables 2 and 4 return to validate assumed

λ = 0.16 to 0.31, seeming

λ = 0.2

But the estimated equations involve explaining level of profit share by lagged dependent variable and the growth rate of productivity

High estimated λ just measures serial correlation in profit share, doesn’t tell us anything about decay in

Schumpeterian profits

Low estimated alpha tells us a low correlation with the level of profit share has growth rate of productivity

Step back from paper, crosssection

If we were trying to explain cross-industry variation in profit share, what factors would we consider?

Surely on the list, ahead of productivity growth would come monopoly power

Microsoft, Intel yes (Nordhaus p. 24)

But also monopoly “Old Economy”: Coca-Cola,

Anheuser-Busch, Gillette, Proctor & Gamble

(toothpaste for $5.99 a tube), over-counter drugs, prescription drugs, and one of Bill’s favorite industries, breakfast cereals

Hi-Tech Brand Names, U. S. Only,

BW, August 5, 2002, p. 95

Rank, Company, 2002 Brand Value ($B)

2 Microsoft 64, 3 IBM 51, 5 Intel 31

14 HP 18, 16 Cisco 16, 17 AT&T 16

23 Oracle 12, 27 Compaq 10, 28 Pfizer 10

31 Dell 9, 50 Apple 5

Total $245 Billion

Non-Hi-tech Brand Names, US only, BW, August 5, 2002, p. 95

Rank, Company, 2002 brand value

1 Coca-Cola 70; 4 GE 41; 7 Disney 29; 8 McDonalds

26

9 Marlboro 24; 11 Ford 20; 13 Citibank 18

15 Amex 16; 19 Gillette 15; 24 Budweiser 11

25 Merrill Lynch 11; 26 Morgan Stanley 11

29 JP Morgan 10; 30 Kodak 10; 35 Nike 8

37 Heinz 7; 39 Goldman Sachs 7; 40 Kellogg 7

45 Pepsi 6; 46 Harley-Davidson 6; 47 MTV 6

48 Pizza Hut 6; 49 KFC 5

Total $372 Billion

Whatever happened to multiple regression?

If profit share depends both on monopoly power and rate of innovation

Why just show us simple correlations when multiple correlations are required?

Maybe Schumpeterian coefficient is actually zero when MS and Intel are eliminated from his hi-tech sample

The “Weakest Link”: What actually creates the observed differences in profit share across industries

Step back from paper, time series

If we were trying to explain time-series variation in profit share, what factors would we consider?

Surely, rather than regressing level of profit share on growth in productivity, we would model the behavior of both productivity and profit share growth in response to cyclical changes in the output gap

Change in hours gap responds partially and with a lag to changes in the output gap

Inflation equations show that only 10-20 percent of productivity gap changes affect prices, remainder spills over to a change in profits

Real Profits through Identities

(please note: identities are a noncontroversial branch of macro)

PY ≡ WN + RK

1 ≡ (WN/PY) + (RK/PY)

1 ≡ S + (1-S)

Lower case letters are growth rates

0 ≡ Ss + (1-S)(1-s)

0 ≡ Ss + (1-S)(r-p – (y-k)) r-p ≡ -(S/(1-S)s + y - k

Productivity Growth Revival and y-k

Y = AF(N,K) y = a + Sn + (1-S)k y – k = a – S(k – n)

Was the post-1995 productivity revival a result of an increase in a or in k-n ?

An autonomous increase in a raises y – k

An autonomous increase in capital deepening reduces y - k

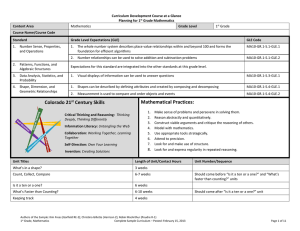

Profit Margins are the Flip Side of

Labor’s Share

Labor's Share

75.0

70.0

65.0

19

59

19

61

19

63

19

65

19

67

19

69

19

71

19

73

19

75

19

77

19

79

19

81

19

83

19

85

19

87

19

89

19

91

19

93

19

95

19

97

19

99

20

01

Labor's Share

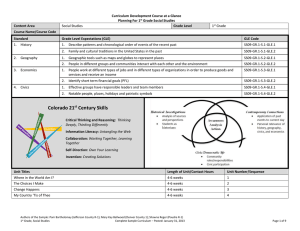

How is the Profit Share related to the Productivity Growth Trend?

16.0

14.0

12.0

10.0

After-Tax Profit Share

Total Profit Share

Moving Avg Prody Growth

8.0

6.0

4.0

2.0

0.0

19

59

19

61

19

63

19

65

19

67

19

69

19

71

19

73

19

75

19

77

19

79

19

81

19

83

19

85

19

87

19

89

19

91

19

93

19

95

19

97

19

99

20

01

Real Profits through Identities

(please note: identities are a noncontroversial branch of macro)

PY ≡ WN + RK

1 ≡ (WN/PY) + (RK/PY)

1 ≡ S + (1-S)

Lower case letters are growth rates

0 ≡ Ss + (1-S)(1-s)

0 ≡ Ss + (1-S)(r-p – (y-k)) r-p ≡ -(S/(1-S)s + y - k

Computing the Change in the Real

Return on Capital (r – p)

1959-73 1973-95 1995-2000 s 0.37 -0.03 0.23

-S/(1-S)s -0.88 0.07 -0.57

y – k 0.32 0.23 -0.39

r – p -0.56 0.30 -0.96

Conclusion #1

The paper is exactly right: New Economy innovations went to workers and consumers, not shareholders

We already knew that from macro data

Cross-section results cannot reveal appropriability because monopoly-type variables are omitted

Conclusion #2

Time-series results contaminated by common co-movement of MFP with profits due to an omitted variable, the Keynesian output gap

What fraction of gains from innovation have been appropriated over the last two centuries? An interesting question for

Bill’s next paper