OH Training Module 4 - Fluoride Therapies

advertisement

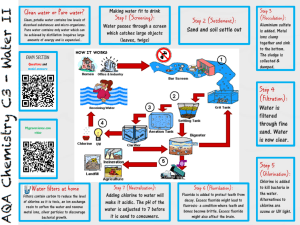

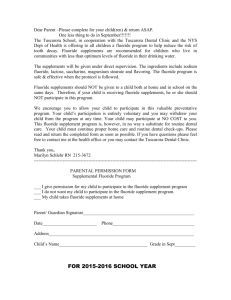

Children’s Oral Health & the Primary Care Provider Fluoride Therapies Module 4 Module 4 Objectives: Discuss fluoride mechanism of action Discuss available fluoride therapies: Fluoride in Water Fluoride in Toothpaste Fluoride Supplements Fluoride varnish Fluoride Mechanism of Action: Main Effect Fluoride (F) enhances remineralization of early lesions & inhibits demineralization of intact tooth structure (topical effect) Fluoride also inhibits caries by affecting the activity of cariogenic bacteria Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The main effect of fluoride is a topical, localized and direct one on erupted or erupting teeth “…frequent exposure to small amounts of fluoride each day will best reduce the risk for dental caries in all age groups…” Available Fluoride Therapies Fluoride in Water Decline in severity & prevalence of caries in 2nd half of 20th century; due in part to water fluoridation Fluoridation is endorsed by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC lists community water fluoridation as one of 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century Fluoride in Water Ideal public health measure No health hazards Provides low-dose (1 ppm) fluoride topically on a nearly continuous or high frequency basis for those consuming it alone, or in foods or beverages made with fluoridated water Very effective, safe, convenient & equitable Very low-cost & excellent cost/benefit ratio Fluoride in Water Fluoride occurs naturally in the water of some geographic locations; especially in Iowa The optimal fluoride level in drinking water is 0.7 – 1.2 parts per million; an amount proven beneficial in reducing tooth decay Naturally occurring fluoride may be below or above these levels in some areas 93% of Iowa’s community water systems are optimally fluoridated Populations Receiving Fluoridated Water in US: 2006 69% of US population received optimally fluoridated water in 2006 Increase from 66% in 1992 Range: 8.4% (Hawaii) to 100% (D.C.) 2010 objective: 75% of US to have access to fluoridated water Underutilized public health measure What is the Fluoride Content in my Water? http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/MWF/index.asp The Controversy About Infant Formula & Fluoride in Water Bottled water is usually low in fluoride. disclosure of F content required only if F added Powdered or liquid concentrate infant formula contains fluoride. manufactured from fluoridated community water supply If formula is reconstituted with fluoridated water, infants could theoretically consume more than the recommended daily fluoride intake. The Controversy About Infant Formula & Fluoride in Water To reduce the risk of mild fluorosis the CDC & the ADA recommend: Use of ready-to-feed formula to help ensure infants do not exceed the optimal daily fluoride intake If concentrate or powdered formula is primary source of nutrition, it can be mixed with water that is fluoride free or contains low levels of fluoride to reduce the risk of excessive fluoride intake. Fluoride Supplements Fluoride supplements are intended to compensate for fluoride-deficient drinking water Dosage schedule requires knowledge of the fluoride content of the child's primary drinking water & other sources of fluoridated water Evidence for using fluoride supplements to mitigate dental caries is mixed Fluoride Supplements http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5014a1.htm Fluoride Supplements: Special Considerations Fluoride supplement should be considered for children who are classified as high risk for caries & live in areas with non-fluoridated water. “Halo effect” – indirect benefit of fluoridated water to nonfluoridated communities Families who are compliant with supplements are often not the ones that need them Dietary Sources of Fluoride Examples of products containing fluoride: Soft drinks & juice – approximate drinking water levels • Grape juice – high fluoride content Tea – high fluoride content Chicken products – high fluoride content Fish products Seafood Fluoride Supplements & Fluorosis Very Mild Moderate Severe Fluorosis in Primary Teeth Less common & less severe than permanent tooth fluorosis Related to water fluoride levels Associated with fluorosis in permanent teeth Primarily a postnatal etiology More common in primary molars; enamel not formed at birth Primary incisor enamel already formed at birth 2nd Baby Molar Fluoride Toothpaste Provides moderate-dose (1000 ppm) fluoride topically; 2-3 times per day Very effective, readily available & low cost Requires active use (people must brush their teeth to receive benefit) Fluoride in toothpaste is taken up directly by dental plaque & demineralized enamel Fluoride Toothpaste Ingestion is a concern in younger children Amount dispensed is a key factor smear ½ pea-sized pea-sized Recommended Amount of Fluoridated Toothpaste by Age Fluoride Dentifrices for Dental Caries Prevention While fluoride dentifrice Melberg, JR. Int Dent J 1991; 41: 9-16 concentrations of 1000 ppm are effective in caries prevention, there is a doseresponse relationship, so that (to some extent) greater fluoride concentrations result in greater caries prevention High Fluoride Toothpaste Provides higher-dose (up to 5000 ppm) fluoride topically once or twice per day Somewhat more effective than conventional toothpaste Requires active use (people must brush their teeth to receive benefit) Prescription only & more costly High Fluoride Toothpaste Recommended for high-caries risk individuals > 6 years of age Used 1-2 times daily like regular tooth paste About $12 per small (1.8 oz) tube Not indicated for children < 6 years due to ingestion Fluoride Mouth Rinses Provides moderate-dose (226 ppm) fluoride topically on a daily (or more frequent) basis Effective, available OTC & moderate cost Alcohol-free mouth rinse Requires active use (people must remember to rinse daily) Not recommended for younger children who can’t rinse & spit Professionally Applied Fluoride Gels and Foams Provides high-dose (12,300 ppm) fluoride topically Under dentists’ control Requires dental visit Contraindicated in younger children ingestion concerns trays are difficult to cope with Professionally Applied Fluoride Varnishes Provides high-dose (22,600 ppm) fluoride topically Under providers’ control Currently an “off-label” use Over 30 years of clinical study More effective than professional gels Majority of studies report 25-45% caries reduction Fluoride Varnish: Practical Advantages No need to be in a dental office for application Locally retained for several hours; varnish may release fluoride for weeks Increase caries-inhibition properties by holding fluoride close to tooth surface for longer duration Potential ingestion of fluoride is low, especially when compared to gels/foams Teeth don’t need professional cleaning (prophylaxis) Prevents caries on smooth & pit and fissure sites Summary Table of Available Fluoride Therapies FlToothpaste High FlToothpaste Fl- Mouth Rinse Gels and Foams Fl- Varnish Moderate (1000ppm) High (5000ppm) Moderate (226ppm) High (12,300ppm ) Very High (22,600ppm ) Requires Compliance OTC Dose Prescription Professional Applied Contraindicate d for younger children No, if in small amounts How Much Fluoride is too Much? Probable toxic dose of fluoride = 5mg F/kg 7kg child (15.4 pounds) 7kg child needs to ingest 35 mg of fluoride to be toxic (nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea) A single dose of .25 mL of fluoride varnish contains 5.65 mg fluoride An adult dose of .50 mL of fluoride varnish contains 11.3 mg fluoride Acute lethal dose = 15–35mg F/kg Summary: Fluoride Therapies Module 4 Fluoride enhances remineralization of early lesions & inhibits demineralization of intact tooth structure Fluoride inhibits caries by affecting the activity of cariogenic bacteria The main effect of fluoride is topical Community water fluoridation is a safe, effective & inexpensive way to prevent caries Bottled water is generally low in fluoride Summary: Fluoride Therapies Module 4 To reduce risk of fluorosis, the use of lower fluoride water to reconstitute infant formula is recommended Distillation or reverse osmosis removes all fluoride from water Carbon or charcoal filters do not remove fluoride “Halo effect” – indirect benefit of fluoridated water to nonfluoridated communities Summary: Fluoride Therapies Module 4 Fluoride toothpaste is very effective, readily available & low cost Ingestion of fluoride toothpaste is a concern in younger children Amount dispensed is a key factor High fluoride toothpaste is recommended for highcaries risk people Not indicated for children < 6 years due to ingestion Fluoride varnish provides high-dose fluoride topically Fluoride varnish is very effective in caries prevention 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. References Leverett DH, Adair SM, Vaughan BW, Proskin HM, Moss ME. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of prenatal fluoride supplements in preventing dental caries. Caries Res 1997;31:174--9. Brunelle JA, Carlos JP. Recent trends in dental caries in U.S. children and the effect of water fluoridation. J Dent Res 1990;69(special issue):723--7. Aasenden R, Peebles TC. Effects of fluoride supplementation from birth on human deciduous and permanent teeth. Arch Oral Biol 1974;19:321--6. de Liefde B, Herbison GP. The prevalence of developmental defects of enamel and dental caries in New Zealand children receiving differing fluoride supplementation in 1982 and 1985. N Z Dent J 1989;85:2--8. D'Hoore W, Van Nieuwenhuysen J-P. Benefits and risks of fluoride supplementation: caries prevention versus dental fluorosis. Eur J Pediatr 1992;151:613-6. Allmark C, Green HP, Linney AD, Wills DJ, Picton DCA. A community study of fluoride tablets for school children in Portsmouth: results after six years. Br Dent J 1982;153:426--30. Fanning EA, Cellier KM, Somerville CM. South Australian kindergarten children: effects of fluoride tablets and fluoridated water on dental caries in primary teeth. Aust Dent J 1980;25:259--63. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. References Marthaler TM. Caries-inhibiting effect of fluoride tablets. Helv Odont Acta 1969;13:1--13. Widenheim J, Birkhed D. Caries-preventive effect on primary and permanent teeth and cost-effectiveness of an NaF tablet preschool program. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1991;19:88--92. Widenheim J, Birkhed D, Granath L, Lindgren G. Preeruptive effect of NaF tablets on caries in children from 12 to 17 years of age. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986;14:1--4. Margolis FJ, Reames HR, Freshman E, Macauley JC, Mehaffey H. Fluoride: ten-year prospective study of deciduous and permanent dentition. Am J Dis Child 1975;129:794--800. Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O, Bruun C, Kann J. Enamel changes and dental caries in 7-year-old children given fluoride tablets from shortly after birth. Caries Res 1979;13:265--76. Bagramian RA, Narendran S, Ward M. Relationship of dental caries and fluorosis to fluoride supplement history in a non-fluoridated sample of schoolchildren. Adv Dent Res 1989;3:161--7. Holm A-K, Andersson R. Enamel mineralization disturbances in 12year-old children with known early exposure to fluorides. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1982;10:335--9. References 15. Awad MA, Hargreaves JA, Thompson GW. Dental caries and fluorosis in 716. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. -9 and 11--14 year old children who received fluoride supplements from birth. J Can Dent Assoc 1994;60:318--22. Friis-Hasché E, Bergmann J, Wenzel A, Thylstrup A, Pedersen KM, Petersen PE. Dental health status and attitudes to dental care in families participating in a Danish fluoride tablet program. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984;12:303--7. Kalsbeek H, Verrips GH, Backer Dirks O. Use of fluoride tablets and effect on prevalence of dental caries and dental fluorosis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1992;20:241--5. DePaola PF, Lax M. The caries-inhibiting effect of acidulated phosphatefluoride chewable tablets: a two-year double-blind study. J Am Dent Assoc 1968;76:554--7. Driscoll WS, Heifetz SB, Korts DC. Effect of chewable fluoride tablets on dental caries in schoolchildren: results after six years of use. J Am Dent Assoc 1978;97:820--4. Stephen KW, Campbell D. Caries reduction and cost benefit after 3 years of sucking fluoride tablets daily at school: a double-blind trial. Br Dent J 1978;144:202--6. Pendrys DG, Katz RV, Morse DR. Risk factors for enamel fluorosis in a fluoridated population. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:461--71. References 22. Pendrys DG, Katz RV. Risk for enamel fluorosis associated with 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. fluoride supplementation, infant formula, and fluoride dentifrice use. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130:1199--208. Lalumandier JA, Rozier RG. The prevalence and risk factors of fluorosis among patients in a pediatric dental practice. Pediatr Dent 1995;17:19--25. Pendrys DG, Katz RV, Morse DE. Risk factors for enamel fluorosis in a nonfluoridated population. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:808--15. Larsen MJ, Kirkegaard E, Poulsen S, Fejerskov O. Dental fluorosis among participants in a non-supervised fluoride tablet program. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1989;17:204--6. Riordan PJ, Banks JA. Dental fluorosis and fluoride exposure in Western Australia. J Dent Res 1991;70:1022--8. Suckling GW, Pearce EIF. Developmental defects of enamel in a group of New Zealand children: their prevalence and some associated etiological factors. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984;12:177--84. Wöltgens JHM, Etty EJ, Nieuwland WMD. Prevalence of mottled enamel in permanent dentition of children participating in a fluoride programme at the Amsterdam dental school. J Biol Buccale 1989;17:15--20. References 29. Woolfolk MW, Faja BW, Bagramian RA. Relation of sources of systemic 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. fluoride to prevalence of dental fluorosis. J Public Health Dent 1989;49:78--82. Ismail AI, Brodeur J-M, Kavanagh M, Boisclair G, Tessier C, Picotte L. Prevalence of dental caries and dental fluorosis in students, 11--17 years of age, in fluoridated and non-fluoridated cities in Quebec. Caries Res 1990;24:290--7. Margolis FJ, Burt BA, Schork A, Bashshur RL, Whittaker BA, Burns TL. Fluoride supplements for children: a survey of physicians' prescription practices. Am J Dis Child 1980;134:865--8. Szpunar SM, Burt BA. Fluoride exposure in Michigan schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent 1990;50:18--23. Levy SM, Muchow G. Provider compliance with recommended dietary fluoride supplement protocol. Am J Public Health 1992:82:281--3. Pendrys DG, Morse DE. Use of fluoride supplementation by children living in fluoridated communities. J Dent Child 1990;57:343--7. Pendrys DG, Morse DE. Fluoride supplement use by children in fluoridated communities. J Public Health Dent 1995;55:160--4. Jackson RD, Kelly SA, Katz BP, Hull JR, Stookey GK. Dental fluorosis and caries prevalence in children residing in communities with different levels of fluoride in the water. J Public Health Dent 1995;55:79--84. References 37. Populations Receiving Optimally Fluoridated Public Drinking Water --- United States, 1992—2006 MMWR July 11, 2008 / 57(27);737-741