1928 - Prosperity - West Morris Central High School

advertisement

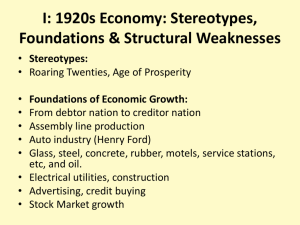

West Morris Central High School Department of History and Social Sciences 1920s Overview Prosperity: 1928 From: The Roaring Twenties, Eyewitness History, Revised Edition. As the year 1928 dawned over the United States, the Republican Party and the public had good reasons for optimism and complacency. The economy of the United States had quickly righted itself after the postwar recession of 1920–21 and had been expanding without pause or retreat for a full seven years. Production increased steadily throughout the Coolidge years; inflation remained moderate and interest rates low. Gross national income reached $89 billion in 1928, a figure representing $745 per capita, from a grand total of $60 billion, or $651 per capita, in 1918. Bank deposits were up; the value of life insurance contracts was rising; after the belt-tightening required by the war and the depression, public authorities were making greater expenditures for new libraries, schools, and hospitals. Compared to a 1919 baseline of $100 per day, five-and-dime stores were doing $260 of business per day in 1927, and grocery chains $387. The real purchasing power of wages rose 20 percent every year between 1915 and 1926. In 1925, 75 people in the United States reported incomes of $1 million; in 1927 there were 283. A key to the economic growth and prosperity in the United States as well as Canada was the one great advantage the two countries enjoyed over their competitors in Europe: they had emerged undamaged from the war, with their manufacturing industries, cities, agricultural land, and transportation systems intact. In both countries, the labor strife of 1919 and 1920 gradually calmed, and the violent controversies over radical politics began to dim in the collective memory. Natural resources were readily available and cheap. Standardization and the techniques of mass production pioneered by Henry Ford allowed large companies to lower manufacturing costs and to sell their goods to an expanding market. The success of Ford and the automotive industry in general had a domino effect on other industries; many other companies took up Ford's policy of high wages and low prices, with work compartmentalized for increased efficiency. Business also had the advantage of Republican presidencies, which in general disfavored business regulation and trust-busting and looked kindly on higher import tariffs that discouraged foreign competition. The business-friendly attitude of Presidents Harding and Coolidge, and the impression of competence and solidity given off by President Herbert Hoover, who would take office early in 1929, contributed to the general confidence felt by investors and consumers. Public authorities were spending a great deal more on libraries, hospitals, and schools and budgeting a steadily rising amount of money on health, education, and social welfare services. The nation was transforming itself into a white-collar society, in which office jobs dominated. Clerks, managers, secretaries, typists, and administrators saw their clean, safe, and well-lit working environs as emblematic of entry into the middle class. This trend particularly benefited women, who still saw the way barred to management jobs in blue-collar industries and manufacturing. The rise in income and the growing acceptance of the eight-hour working day on the part of employers gave workers more time to spend at their leisure. Car camping came into vogue in the 1920s; spectator sports found a mass audience, and middle-class amateurs took to formerly upper-crust sports such as golf and tennis. A crucial ingredient of the economic expansion of the 1920s was the changed behavior of retail customers, who began adopting the habits of modern consumers. Millions of buyers sought out electronic gadgets that made home life easier or more entertaining: washers, refrigerators, electric irons, vacuum cleaners, toasters, electric sewing machines, and radios. By the same token, the complex designs of these items and their dependence on the unpredictable, mysterious powers of electricity made them fragile and expendable-to be thrown away for the next model and a new purchase. Advertising agencies made it their business to convince the public of the necessity of these new and improved goods, for the sake of harmony and ease at home. New maladies-bad breath and body odorwere overcome with new products in the personal hygiene line. Fictional advisers, such as General Mills's Betty Crocker, appeared to warn housewives against any neglect of their domestic duties. Household income did not necessarily keep up with the available venues in which to spend it, and so the modern concept of installment buying on credit was born. Low, easy monthly payments were contracted for the purchase of furniture, appliances, clothing, and luxury items such as carpets and pianos. Installment buying represented a radical departure from the old virtues of saving and economy. The product whose sales benefited most from the new concept of paying month-by-month was the automobile. The last holdout against installment buying in the automotive industry fell in 1927, when Henry Ford unveiled the Model A and reluctantly joined competitors such as General Motors in allowing his customers to pay in the future. To increase their productivity, the manufacturing industries of the United States adopted new principles of scientific management that were intended to turn the standard factory into an entirely logical and efficient producer of finished goods. (An official government oversight bureau was inaugurated: the Division of Simplified Practice, which lay within the Department of Commerce led by Secretary Herbert Hoover.) New machinery was invented and installed with the goal of speeding up assembly and reducing the amount of manual labor involved. For many workers, scientific management meant the disappearance of skilled jobs, which were supplanted by repetitious, automated tasks, in which skill was unnecessary. For the national economy, the overall result of this streamlining was an increase in percapita production, a steady rise in national income, and better returns for the holders of company shares in the public stock markets. Scientific management was applied most ferociously in the new auto industry. Although Henry Ford had pioneered the conveyor belt and the assembly-line worker's rigidly defined task, Alfred Sloan of General Motors applied scientific management to every facet of his organization-from top management down to nuts-and-bolts assembly. While auto production per man-hour increased sharply through the 1920s, related industries such as tires and petroleum refining also grew with the new transportation. Autos became affordable to the workers who built them; the benefits of personal transportation trickled down to the middle class, then the working class. The map of the United States grew more complex, with a network of roads now accompanying the steady black lines that indicated railways and canals. Gravel and dirt roads, which rutted and crumbled underneath the balloon tires of heavier Fords, Chevrolets, and Buicks, were replaced by concrete and hard asphalt, which allowed the United States to build the most extensive and up-to-date system of roads in the world by the 1920s. New road building brought an increase in land values away from the cities, as suburbs sprang up to accommodate middle-class workers just beginning their escape from changing conditions in the inner cities. Public spending played an important role, as the federal government granted one-half of the total cost of new interstate highways and trunk highways to local authorities. Uncertain Good Times Despite the impressive statistics, the benefits of the economic good times were spread unevenly among the regions and social strata of the country. The Middle Atlantic and industrial regions of the Midwest prospered from the rapid growth in manufacturing industries, especially in industries directly related to the making of motor vehicles. At the same time, in New England, older manufacturing industries such as textile milling and shoe manufacturing waned. Companies in the mining industry suffered from competition and low returns, with miners suffering the most with stagnant and in some cases falling wages, a situation unresolved by their weakening labor unions. In the agricultural states of the Midwest, in the South, and in the Rocky Mountain states, low prices for agricultural staples such as corn and wheat brought long-lasting economic stagnation that found no relief in the growth of cities or improvements in transportation. Heavily in debt for the purchase of their land or machinery, farmers went bankrupt by the thousands and saw their homes and acreages foreclosed on by small-town banks, a condition that foreshadowed economic disaster in the Midwest during the 1930s. The problems in farming and mining regions intensified the general migration of the population into the nation's cities. In addition, unemployment in the United States did not disappear with the well-advertised prosperity of the Roaring Twenties. The unemployment rate's low point was reached in 1926, when 1.8 percent of the civilian labor force was out of work. From that point, unemployment again began to rise, reaching 4.2 percent in 1928, falling to 3.2 percent in 1929, and jumping to 8.7 percent in 1930, at the start of the Great Depression. At the same time, the labor movement was losing steam. No longer short of labor for wartime production demands, companies laid off workers, cut wages, and hired scabs and strikebreakers to deal with any trouble. Large manufacturing companies given impetus by the war effort were unsympathetic to unions, as managers of this era had little firsthand experience of blue-collar work. Where workers made an attempt to organize, the bosses replied with company unions, which were under the ultimate control of management. Independent unions lost their bargaining power and still suffered from the bad reputation of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose strikes in the previous decade has been a deliberate attempt to undermine the war effort. IWW members and their leader, Big Bill Haywood, were still condemned as traitors, an opinion seemingly confirmed when Haywood jumped bail in 1921 and fled to the Soviet Union, where he died in 1928. Dissent in the ranks of unionized workers worsened. The union movement was dividing between trade unions, which organized according to craft, and industrial unions, which organized entire industries. Samuel Gompers, the longtime president of the American Federation of Labor, staunchly resisted industrial unions as a direct threat to his organization. Industrial unions were gaining strength through the automation of factory work, and especially auto production, which created a growing class of semiskilled workers laboring for bare-minimum wages. In these hard times, a few successful labor leaders emerged in the1920s. During World War I, John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers (UMW) had negotiated a substantial raise for his union in exchange for an agreement not to strike for the duration of the war. In November 1919, Lewis led the miners out for better wages; the government responded with a threat of prosecution for breaking the antistrike injunction. On January 1, 1920, Lewis was named president of the UMW, replacing Frank Hayes. Lewis won another wage increase in August 1920 but was defeated by Samuel Gompers for the presidency of the AFL in 1921. John Lewis sought to unify the hundreds of small local unions that bargained on their own. His goal was uniform nationwide contracts. But a postwar depression in the mining industry made his position difficult. Mines were closing and miners were losing their jobs. Union membership fell, and in 1924, Lewis had to hold the union wage at $7.50 a day. This agreement expired on April 1, 1927, when conditions were no better. As the price of coal fell, the UMW disappeared in many places and wages plummeted. The UMW lost about 90 percent of its membership in just a few years. The Great Depression of the 1930s would nearly finish the union. Mary "Mother" Jones had spent decades striking and marching with miners all over the country, on several occasions getting herself beaten and arrested. Jones's home field was western and southern West Virginia, where coal mining employed entire towns and counties and where violence among police, company guards, professional strikebreakers, and miners was commonplace. In Mingo County, a May 1920 shootout killed 10 men, including the mayor of the town of Matewan. On August 1, 1921, a group of mine guards shot the sheriff of Matewan, Sid Hatfield, believed to be sympathetic to striking miners. In response to Hatfield's murder, Mother Jones called on miners to march to the Mingo county jail where the stage was set for all-out war. The governor called out the militia and arranged for aerial bombing of the strikers. Seeing the potential for a massacre, Jones called off the march and brandished a telegram from Warren Harding, promising to investigate. Without actually producing Harding's words, Jones fled the state. The strike ended soon thereafter. Philip Randolph and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Born in 1889 in Crescent City, Florida, Asa Philip Randolph was a minister's son who found a small southern town no match for his wide-ranging abilities and curiosity. On moving to New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1911, he enrolled at City College, which at the time provided a free education for city residents. A series of menial jobs, particularly one stint as a restaurant sidewaiter, convinced him that the capitalist system was exploiting him and other African-American workers. Cooperation, not competition, was the wave of the future, in Randolph's opinion, but his union-organizing attempts in New York resulted only in his getting fired, several times. After joining the Socialist Party of America in 1916, Randolph founded the Messenger, which soon became one of the nation's most popular African-American journals. In the Messenger's pages, he extolled socialism and criticized the government, politicians, and even mainstream labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL), many of whose member unions banned black workers. The IWW, which did not discriminate, won Randolph's enthusiastic support. Instead of reform, Randolph wrote and spoke in favor of a transformation of the economic system into something better than capitalism. However, World War I was a very bad time to be associated with the IWW or to be publicly criticizing the government and the nation's economic system. Police staged several raids on Messenger offices, and in 1918, Randolph was arrested at a rally in Cleveland. The postwar violence and continuing government repression inspired Randolph to begin forming black trade unions, including the National Brotherhood Workers of America. All of them failed for lack of members and money. In June 1925, Randolph received a message from Ashley Totten of the Pullman Porters Athletic Association, inviting him to form a union for the men working as Pullman train porters. About 10,000 of these porters worked as butlers and waiters on the cross-country sleeping cars of the Pullman Palace Sleeping Car Company. Established in the years after the Civil War, the company hired former slaves to work in its cars. By the 1920s, the Pullman porters were working exhausting hours for low wages and were treated as indentured servants by the company. They had failed to organize and, without union organization, were unsuccessful in gaining any improvement in their wages or working conditions. Pullman summarily fired anyone suspected of organizing or joining a union. For that reason, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was organized in total secrecy. Randolph traveled around the country to organize locals and prepare his demand for a rise in wages, a lowering of working hours, and recognition of his union. For Randolph, the effort represented something much bigger than a railroad union. He saw the Brotherhood as the first step in developing a mass movement of unionized black workers. Pullman responded to Randolph's organizing efforts by establishing a company union and submitting a Plan of Employee Representation to its members. The company then claimed that a majority of its workers had voted for this plan. Randolph submitted the matter to the mediation board and refuted the company's claim by showing that the workers had been forced to vote for the plan under threat of losing their jobs. Randolph finally announced plans for a strike to begin on June 8, 1928. The company immediately hired replacements and announced that all striking workers would be fired. William Green of the AFL advised Randolph to call off the strike, pointing out that, in an unskilled job such as railroad porter, the Pullman company could legally and easily use replacement workers. As if to back up Green's warning, Pullman then proceeded to fire all of its workers who it suspected had voted to strike. Randolph backed down, but then made the Brotherhood an affiliated union of the AFL. In 1929, the 11,000-strong Brotherhood held its first convention and voted Randolph as its first president. The depression that hit after the stock market crash of 1929 put the Brotherhood and all other unions on the ropes. Most workers considered themselves fortunate just to be employed, and companies found a ready pool of unorganized labor for the purpose of scabbing and for breaking strikes. In his 1932 campaign, Democratic presidential nominee Franklin Roosevelt promised to address the situation. In 1933, soon after Roosevelt's victory, the unions scored an important victory with passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act. The act set a minimum wage and maximum working hours and gave workers the right to form unions and the right to collective bargaining with their employers. Although the legislation banned company unions, it had also defined the Pullman Company as a common carrier, which exempted it from the law. In 1934, Congress amended the Emergency Railroad Transportation Act to include the Brotherhood. The company responded by ordering porters to form the Pullman Porters Protective Association. The matter went to the federal board of mediation, which ordered an election that Randolph's union won by a six-to-one ratio. In 1935, the Brotherhood won legal recognition. The case went as far as the Supreme Court in 1937, when the Pullman company finally began negotiating, 12 years after the founding of the Brotherhood. On August 25, 1937, Randolph finally agreed to the first contract between a black union and an American corporation. Democratic Conventions With all the prosperity and newfound comforts in 1928, the leaders of the Democratic Party knew they would find themselves hard-pressed to mount effective opposition to the Republicans in the upcoming presidential election. Yet compared to the rancorous nominating contest held at Madison Square Garden in 1924, the Democratic convention of 1928, held in Houston, was trouble-free. Delegates and managers took care to avoid controversy and division. There were no roll call votes, no floor fights, no debates over the party platform or over politically charged resolutions. The easy winner, apparent to all from the first day, would be New York governor Al Smith. Democratic delegates favored Smith, an Irish Catholic born to immigrant parents, for his successful and energetic governorship of New York and found in him a perfect representative of the country's accelerating urbanization and the wider acceptance of immigrants and their descendants into the mainstream. Smith, on his side, carefully avoided the question of Prohibition repeal; although all knew him as a "wet" candidate, Smith pledged to uphold the Eighteenth Amendment as the law of the land. This time around, Smith nearly won on the nominating convention's first ballot, and finally did win with new votes from the Ohio delegation on the second. His running mate, Senator Joseph Robinson of Arkansas, provided balance as a rural-state Protestant and a supporter of Prohibition. Smith went with the tenor of the times for his campaign by appointing as a campaign manager his cultural opposite: John J. Raskob, a wealthy Republican and former executive with General Motors. Smith knew he could count on a loyal Democratic vote in the South; by appointing Raskob, he also intended to capture some of the business vote, especially those who felt out of touch with Prohibition. Raskob was best known among the voters for his opinion that good stocks should sell at 15 times their earnings, rather than the traditional 10 times, a sentiment that was giving an additional boost to the already overheated stock market. He was also known for supporting Calvin Coolidge in 1924. Although Smith came out for high tariffs to please Republican business interests, who wanted foreign competition lessened and their profits protected, his statements pleased neither Republican nor Democratic constituencies. The choice of Raskob also left many in the Democratic Party distinctly unenthusiastic. They saw the choice as a sellout by Smith and believed that the appointment of the conservative industrialist signaled an end to any faint chance the country had for Progressive-style social and business reforms. Although Smith did manage to win some business support, many liberal Democratic voters turned from their party's nominee to Norman Thomas, the Socialist candidate. In the Midwest and South, where New York and other big cities signified crime and corruption, Smith was also under suspicion for his New York accent and for his parents-working-class Irish immigrants who lived on the big city's Lower East Side. Despite his promise to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment, his anti-Prohibition sentiments gave dry opponents a clear line of attack. Above all, Smith's Catholicism proved to be a problem in a land where many still held to the myth of the nation's agrarian, small-town, Protestant origins. Before the 1928 candidacy of Al Smith, no Catholic had appeared on the presidential ballot, and the country had a long memory of anti-Catholic violence that flared up with the arrival of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and then southern Europe. Smith's opponents did not hesitate to raise pointed questions on the subject of his religion: Would a Catholic president hold some kind of secret allegiance to the pope and the Vatican? Would he oppose the fundamental principle of separation of church and state? Hoover's Rugged Individualism Before the Democrats met in Houston, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover had won the Republican nomination for president in Kansas City by beating back a challenge from Frank Lowden of Illinois, who ran on a plank supporting protection and price support for the country's struggling farmers. Hoover himself seemed to supply something that the 1920s lacked: a spirit of public service, instilled by his Quaker upbringing and carried out most famously with his term as War Food Administrator and his relief work in Europe during and after the war. Hoover praised rugged individualism but also community service and sacrifice that went beyond the virtues of self-interested capitalism. Hoover's turned out to be the much simpler campaign. The candidate voiced the easy opinion that the prosperity was due to Republican laissez-faire policies and promised the voters that the day was not far distant when poverty would disappear. To discourage the undecided against the Democrats, he warned against the dangers of government ownership and management, threatened by the more socialistic members of his rival party. The result was a victory in November by a margin of 444 electoral votes to 87, while the Republican Party carried majorities in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Democratic partisans could take some comfort after a close examination of the results. The Democratic South had been broken up-Smith lost five Deep South states to Hoover as well as his home state of New York. Nevertheless, Smith had won more votes than any Democratic presidential candidate in history. Raskob had actively campaigned in the northern farm belt where Smith cut down the Republican majorities of the previous two elections and also captured the progressive voters who had supported Robert La Follette. The election of 1928 also began the trend of bringing laborers and recent immigrants onto the Democratic side of the ballot. Also, for the first time, the Democrats won a majority in the nation's 12 largest cities. The union vote, the working classes, and the immigrant vote, especially among Catholic immigrants from Canada, Italy, and Ireland, went into the Democratic column and would stay there for another 50 years. Wall Street Enthusiasm Politics and the election of 1928 proved of much less interest to the country at large than the more straightforward affairs of business and the stock market. The market was attracting crowds of speculators and torrents of new money that sparked a wave of buying fever during the year. In addition to the traditional wealthy buyers and sellers, the members of the growing middle class bought in, many of them considering a plunge (buying stocks) on the shares of RCA or Standard Oil as a hallmark of arrival into the ranks of the leisure class. Branch offices of big-city brokerages opened in small-town storefronts, while price quotations ran in the daily newspapers and on brokers' tote boards and chattering telegraphic stock tickers spun out Wall Street's ups and downs in corporate offices. As always, word-of-mouth news and information proved most convincing, and the hottest rumors of the 1920s concerned instant riches earned on Wall Street by butlers, gardeners, chauffeurs, maids, clerks, and barbers-ordinary people providing themselves with an early retirement courtesy of Wall Street. The stock market boom reached its peak in the early spring of 1928, when people all over the country withdrew their savings to play the market. In March and April, trading volume exceeded 3 million shares on 33 separate days; between 1925 and 1928, the same volume had only been attained six times. On one day in May, volume reached the staggering figure of 4,800,000 shares. Several times, the feverish trading prompted the officers of the exchange to suspend business so that brokers could bring their books and records current; in May trading hours were cut from five to four in order to provide relief for exhausted members of the exchange. A large percentage of the brokerage accounts were trading on margin, or money borrowed from the brokers by the investors. This practice imitated the new method of installment buying that the public had adopted for purchases of automobiles and household goods (by the end of the 1920s about 15 percent of all purchases were made on credit). On Wall Street, margin buying contributed to the speculative fever; as stock prices rose, so did the value of one's collateral-shares of stock-thus encouraging more borrowing and more buying. The danger of falling prices and margin calls (the demand for repayment of loaned money by the brokers) was disregarded. In general, stock prices did not fall, and when they did, they usually recovered and subsequently reached new highs. Margin calls were rare, and the paper profits of individuals as well as banks and corporations-many of which had nothing better to do with their money than to throw it at the market as well-formed an immense financial pyramid that, as the decade wore on, gradually uncoupled itself from the actual performance of individual companies and the national economy. At the same time, the government's laissez-faire economic policies encouraged the formation of new corporations whose dubious operations included little in the way of actual production or sales. In certain states such as Delaware newly formed companies could issue stock with no obligation whatsoever to make a regular financial accounting or an annual report to shareholders. A common practice was the establishment of "holding companies" from the assets of a network of local utility companies. The organization of these companies was purposefully made as complex and opaque as possible. Investors could discover very little about their assets, liabilities, income, or profit, and in many cases did not care. In fact, the true purpose of organizations such as Electric Bond and Share, Standard Gas and Electric, and Cities Service was to enrich their founders and directors through issuance of new stock certificates and through inflated rises in the price of their shares. The traditional benchmark of paying 10 times earnings for a share of stock was forgotten during the stock market run-up. Stocks traded for 20, 30, even 100 times their earnings simply on the expectation that share prices would always, sooner or later, continue to rise. The hot rumors and stock tips and the good business the country was doing made it easy to gamble one's savings on the market, which seemed to be holding to a single direction: up. New technology-placing orders by telephone and getting quotations by the radio-made trading on stocks in the market easier than ever and, for the first time, accessible to the nonwealthy. Many ordinary working people took great interest in price movements as detailed in the financial pages of the daily newspaper; many also trained themselves to read historical price charts, summoning the future by examining the pattern of rising and falling lines on a graph. Waiters, delivery boys, actresses, and others traded on tips they garnered through the vast, national investment grapevine. For the first time, bankers and brokers actively solicited new clients, instead of passively waiting for customers to appear in their lobbies. (In some cases, stock market investing was rather involuntary: employees of holding-company president Samuel Insull were expected to buy shares in his firm; these investors in turn sold Insull's shares to customers, friends, and acquaintances.) Brokers' offices in Manhattan moved uptown; new offices opened in small towns and big cities while the brokerages increased staff and raised new buildings. Bustling trade rooms were kept open to the general public, who were welcome to take a seat and enjoy the spectacle of clerks running about the room collecting order slips, clerks standing by the quote board to erase and rescribble the numbers indicating prices and volume, and clerks standing by to open accounts, accept checks, fill out paperwork, deliver messages, and open doors. Underneath it all were ominous signs of economic trouble, if investors cared to look and analyze. The profit motive contributed to a rise in earnings for corporations, but the profits were distributed to shareholders rather than workers. The result was a disparity between the earnings of workers and their bosses that grew wider as the decade progressed. Industrial plants were overbuilt, and manufacturing capacity expanded beyond the ability of the society or of foreign markets to absorb the products being made at such a frenetic, albeit scientifically managed, rate, even if workers were being paid enough to purchase cars or houses. The construction boom peaked in 1925 and immediately began a long slide. Car sales were sluggish; several important sectors-textiles, coal mining, agriculture-were going through semipermanent recession. Unemployment nagged at the economy and at society; the growing efficiency at manufacturing plants caused a surplus of manual laborers. There was yet no system of unemployment insurance, so the loss of a job often meant loss of a home. Holding companies in electric power, railroads, and banks encouraged concentration of profits and income in the hands of the few. The banking system had serious weaknesses; most banks were still small and independently run, and a failure (common enough in the agricultural areas of the Midwest and South) could bring a chain reaction, unmitigated by any form of corporate bailout or federal deposit insurance. In the boom times of 1921 to 1928, a total of 5,000 banks closed down. The unregulated banking system was riddled with irresponsible speculation on the part of bankers, many of whom played with their depositors' money on Wall Street with disastrous effects. By the time of Herbert Hoover's presidency, some bankers and federal officials were growing uneasy over the rise in risky margin trading. They debated raising the discount rate (the interest rate charged to banks by the Federal Reserve Board) in order to slow down speculation and margin lending. Higher interest rates, it was assumed, would make borrowing more costly for stock speculators and thus reduce the returns they expected on their investments. During the first two Republican administrations of the 1920s, the Federal Reserve Board appointees had emulated the laissez-faire policies of their presidents, believing that the best policy was to do nothing, allow the free market to run its course and if necessary apply its self-corrective functions. President Coolidge had set the tone. A frugal saver who never invested a dollar in the stock market, Coolidge did not believe in interfering with the market or with the laws of supply and demand, to which he gave most of the credit for "Coolidge prosperity." In July 1928, the government finally took action to cool the fervid stock trading and margin buying by raising the "rediscount" rate of interest, to which margin rates were pegged, to 5 percent. The slight credit tightening did nothing to break the speculative fever. Just after the election of Herbert Hoover, on November 30, 1928, shares of Montgomery Ward rose to 439. Most spectacular and most prominent in the financial pages were the rocketing shares of RCA. First listed on October 1, 1924, at about $26 a share, RCA gyrated through the 60s and 70s in 1925 and 1926, reached $101 in 1927, dipped to 85 in February 1928, and by the end of that year was peaking at $420, just before a stock split that made five new shares for every single old share and paved the way for the expected easier buying, more speculation, and higher market capitalization to benefit the company. But in that cold month of December, a sudden and unexpected drop occurred at the New York Stock Exchange. In a single day, shares of RCA lost more than $70. Fearing a crash, the Federal Reserve governors chose not to raise interest rates again. Doing so, it was believed, would cut off new business investment and make borrowing money more expensive for the federal government. The crisis soon resolved itself in early 1929 as the market regained its balance and continued its inexorable, inevitable rise. In the meantime, harbingers of economic depression first began appearing on the prairies of western Canada. While wheat prices remained low but fairly constant through the 1920s, farmers in the U.S. Midwest as well as Canada were able to survive. But a drop in wheat prices in the late 1920s, caused by a market softened by imports from Argentina, and by the recovery of European agriculture from the damages inflicted by World War I, began causing severe hardships in North America. Farmers, who always seemed to be in some sort of difficulty, attracted little concern outside the states and provinces of the two countries where they still formed an important economic sector. Few suspected that equally damaging imbalances were growing in manufacturing and retail industries, and that the rising stock market disguised fundamental problems that would contribute to economic disaster in the following year.