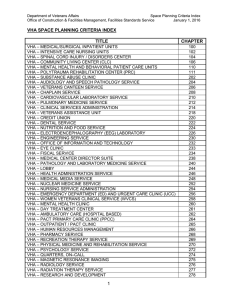

Aspects of Electronic Health Record Systems

advertisement

2012 VHA Innovation Research Jorge A. Ferrer M.D., M.B.A. Informatician Department of Veterans Affairs VHA 1 Study: Physician Perceptions of Two Electronic Medical Records (EMRs): VistA (VA) and GE Centricity Lisa Grabenbauer, University of Nebraska Medical Center (2009) Research Objective: Examine physicians’ perspective on the objective benefits and limitations of current EMR Conclusions: Current EMR frustrates physician collection of data to improve patient care with cumbersome interfaces and processes Recommendations: EMR must provide seamless and flexible interfaces across system boundaries, for data input as well as data retrieval EMR should facilitate patient and team interactions, not inhibit them 2 Study: Karsh, Ben-Tzion, Matthew B. Weinger, Patricia A. Abbott, and Robert L. Wears. "Health Information Technology: Fallacies and Sober Realities." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association17.6 (2010): 617-23. • “The ‘We Computerized the paper, so we can go paperless ‘ fallacy” Taking the data elements in paper-based healthcare system and computerizing them unlikely to create an efficient and effective paperless system This surprises and frustrates Health Information Technology (HIT) designers and administrators The reason is designers do not fully understand how the paper actually supports users’ cognitive needs Computer displays are not yet as portable, flexible or welldesigned as paper 3 References: Computer-based documentation • Aspects of Electronic Health Record Systems. Ed. Harold P. Lehmann, Patricia A. Abbott, Nancy K. Roderer, Adam Rothschild, Steven Mandell, Jorge A. Ferrer, Robert E. Miller, and Marion J. Ball. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science Business Media, 2006. p310. Print. Health Informatics Series. – “Relevant strengths and weaknesses of each note-capture mechanism vary. Fully structured coded notes, for example, facilitate data collection for research and real-time decision support but can be cumbersome to use during patient encounters and may lack the flexibility and expressivity required for general medical practices.” – “Handwritten notes, by contrast, are extremely flexible and permit a high degree of expressivity but may be limited in their legibility and accessibility for data processing and analysis.” 4 References: Computer-based documentation • Aspects of Electronic Health Record Systems. Ed. Harold P. Lehmann, Patricia A. Abbott, Nancy K. Roderer, Adam Rothschild, Steven Mandell, Jorge A. Ferrer, Robert E. Miller, and Marion J. Ball. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science Business Media, 2006. p310. Print. Health Informatics Series. – “ Transcribed notes permit facile documentation into a format possibly useful for machine-based natural language processing for content extraction and summarization but are expensive to produce and require a time delay for the transcription process to occur. “ – “It is likely that each note-capture mechanism will find a clinical niche, with different clinicians and different sites each using the type that best fits the practice situation of the moment and that will vary during the course of a day.” 5 Innovations in Health IT Office National Coordinator (ONC) Grantee and Stakeholder Summit Nov 2011 http://www.tvworldwide.com/events/hhs/111117/def ault.cfm?id=14109&type=flv&test=0&live=0 6 Innovations in Health IT • “Original thinking is the hardest work there is; it is also the most rewarding.” • -Jay Walker • TEDMED, LLC (chairman and a partner). TEDMED is an annual innovation summit for healthcare, bringing together accomplished individuals from many fields of technology, medicine and business to exchange ideas and work on difficult medical problems. 7 Innovations in Health IT The 5 “D’s” of big change (Walker) • Stage 1 Dismissed “you are wasting my time” • Stage 2 Delayed “not now where busy” • Stage 3 Disruption “early adopters come in” • Stage 4 Dominoes “must have solution” • Stage 5 Dominance “change is status quo” 8 AMIA’s Invitational Health Policy Meetings 2006: Toward a National Framework for the Secondary Use of Health Data 2007: Advancing the Framework: Use of Health Data 2008: Informatics, Evidence-based Care, and Research; Implications for National Policy 2009: Anticipating and Addressing Unintended Consequences of HIT and Policy 2010: Future of Health IT Innovation and Informatics 2011: Future State of Clinical Data Capture and Documentation 2012: Uses of Health Data 9 AMIA’s 6thAnnual Policy Meeting The Future State of Clinical Data Capture and Documentation December 6-7, 2011, Washington, D.C. • AMIA’s 2011 Annual Health Policy Conference considered the future of clinical data capture, content and documentation with its challenges and opportunities. Because of the importance of high quality clinical documentation and data in supporting patient care, and given current initiatives encouraging the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs), it is crucial to understand how documentation and data capture processes and policies may be affected by “going electronic.” 10 Time spent on documentation • 21% of time documenting – Annals Emergency Medicine. 1998;31:87-91 • 21% of time documenting – Annals Family Medicine. 2005;3(6):488-493 • 1.4 hour/day – Journal Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(24):4722-4726 • Up from 0.3 hours/day in 1976 11 12 AMIA 2011 meeting assumptions • Need to transform the way we capture data and document clinical care • New technological and technical advances for clinical data capture and documentation • New and diverse data sources, health technologies and devices for data acquisition, collection and reporting, treatment support, and information dissemination • Blurring of lines between devices and applications intended primarily for use by providers, and those intended for patients • Dynamic environmental factors, trends and issues impacting clinical data capture and documentation 13 AMIA working definitions Clinical documentation [and data capture] refers to findings, observations, assessments, and care plans that are recorded in an individual's health record. It may include data entered using various methods, such as computer entry, document scanning, voice dictation, and automated acquisition from devices. An individual’s health record is the repository of clinical information recorded about that person. The record has many functions. 14 AMIA Guiding Principles Clinical data capture and documentation: 1. Be clinically driven and patient-centric –reflecting an individual’s longitudinal and lifetime health status 2. Be efficient –enhancing overall provider efficiency, effectiveness and productivity 3. Be accurate, reliable, valid and complete –enabling high quality care 4. Support multiple uses –including quality and performance measurement and improvement, population health, policymaking, research, education, and payment 5. Enable team collaboration and clinical decision making –including the patient as a member of the team 6. Reflect input from multiple sources –including nuanced medical discourse, structured items and data captured in other systems and devices 15 Usability Present and Future Current Practice and Future Plans for Usability Experience: “Industry Perspective” for the Department of Veterans Affairs SHARPC AMIA Pre-Symposium Dec 2011 W. Paul Nichol, MD VHA Office of Informatics and Analytics • • • • • CURRENT VistA/CPRS USABILITY CHALLENGES Electronic representation of paper chart Dated infrastructure and technological approach Challenges in rapid change Clinical practice 16 2012 VHA Innovation sandbox • PURPOSE STATEMENT – Improve Veterans' health and health care by using medical innovation and information technology. Ideas should address quality, safety, efficiency, and transparency for Veterans. 17 2012 VHA Innovation sandbox • Systems Redesign: Ideas that improve the way our system works. Examples include: improving best practices, design and reliability. The outcome of the idea should address quality and patient safety. 18 2012 VHA Innovation sandbox • Topic: Systems Redesign • Description: Systems Redesign comprises ideas dealing with overall workflow improvement and performance monitoring. “Quality is a system property.” This category focuses on improving how our health care system functions. Innovations in this category could have local or national implications and the outcome should address quality and patient safety. • Challenge: Is there a system process, policy or architectural change that could be improved? How can patient flow be improved? How could new technologies help your systems? Are there better ways to measure or assess systems? How can processes be made more reliable? What can be done to make the business of providing health care more efficient? How can supply chain management be improved? 19 2012 VHA Innovation sandbox • INNOVATION EVALUATION CRITERIA • Innovations should address one or more of the following criteria: – – – – Improve patient care (e.g., safety, quality or access) Improve efficiency (e.g., clinical workflow, cost/benefit) Impact numerous Veterans, staff or other stakeholders Address an unmet need rather than incrementally improve existing methods – Address team qualifications, approach, and environment – Support green initiatives 20 2012 VHA Innovation references 1. 2. 3. 4. Aspects of Electronic Health Record Systems. Ed. Harold P. Lehmann, Patricia A. Abbott, Nancy K. Roderer, Adam Rothschild, Steven Mandell, Jorge A. Ferrer, Robert E. Miller, and Marion J. Ball. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science Business Media, 2006. p310. Print. Health Informatics Series. Karsh, Ben-Tzion, Matthew B. Weinger, Patricia A. Abbott, and Robert L. Wears. "Health Information Technology: Fallacies and Sober Realities." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 17.6 (2010): 617-23. Hartzband, P., and J. Groopman. "Off the Record — Avoiding the Pitfalls of Going Electronic." New England Journal of Medicine 358 (2008): 1656658. AHRQ. Electronic Health Record Usability: Interface Design Considerations. By D. Armijo, C. McDonnell, and K. Werner. No.. 9(10)0091-2-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, October 2009. 21 2012 VHA Innovation references 5. Schiff, G. D., and D. W. Bates. "Can Electronic Clinical Documentation Help Prevent Diagnostic Errors?" New England Journal of Medicine 362 (2010): 1066-069. 6. Payne, T. "Transition from Paper to Electronic Inpatient Physician Notes." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 17 (2010): 108-11. 7. Simon, S. R., R. Kaushal, P. D. Cleary, C. A. Jenter, L. A. Volk, E. G. Poon, E. J. Orav, H. G. Lo, D. H. Williams, and D. W. Bates. "Correlates of Electronic Health Record Adoption in Office Practices: A Statewide Survey." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 14.1 Jan-Feb (2007): 11017 8. Blumenthal, D. "Stimulating the Adoption of Health Information Technology." New England Journal of Medicine 360 (2009): 1477-1485. 22 2012 VHA Innovation references 9. Porter, M.d., Michael E. "What Is Value in Health Care?" New England Journal of Medicine 363 (2010): 2477-481. 10.Jha, A. K., C. M. DesRoches, and E. G. Campbell, et al. "Use of Electronic Health Records in U.S. Hospitals." New England Journal of Medicine 360 (2009): 1628-638. 11.Shea, S., and H. Hripcsak. "Accelerating the Use of Electronic Health Records in Physician Practices." New England Journal of Medicine 362 (2010): 192-95. 12.DesRoches, C. M., E. G. Campbell, and S. R. Sao, et al. "Electronic Health Records in Ambulatory Care -- a National Survey of Physicians." New England Journal of Medicine 359 (2008): 50-60. 13.Sequist, T. D., T. Cullen, H. Hays, M. M. Taualii, S. R. Simon, and D. W. Bates. ". Implementation and Use of an Electronic Health Record within the Indian Health Service." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 14.2 (2007): 191-97. 23