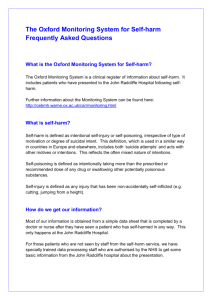

Self-Harm Awareness - Purdue University Calumet

advertisement

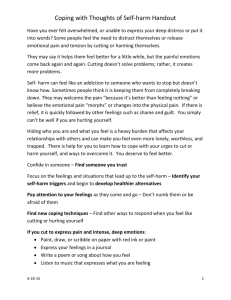

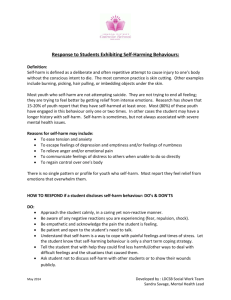

Purdue University Calumet Self-harm is the act of intentionally inflicting harm on oneself. This term can include a range of wide behaviors such as attempted hanging, impulsive, self-poisoning, and superficial cutting in response to intolerable tension. It isn’t a suicide attempt, though it may look and seem that way. Common types of self-injury include: o scratching, o burning o ripping or pulling skin or hair o self-bruising, and breaking bones o While cutting may occur on any part of the body, it is most common on the hands, wrists, stomach, and thighs. Self-injury is an unhealthy way to cope with emotional distress. Some people cut themselves when they feel overwhelming sadness, anxiety, or emotional numbness. Others do it to feel in control or relieve stress. A few see it as a way to “purify” their bodies. Females tend to cut themselves more than males do, although cutting can happen with anyone. It often begins between the ages of 12 and 15, but studies suggest 30-40% of college students who cut begin at 17 years or older. There are many ways in which people self-harm, these can include: o o o o o o o o Cutting or burning their skin Punching themselves Banging or scratching the body Breaking bones Hair pulling or picking skin Self strangulation Ingesting toxic substances Deliberately starving themselves Misusing alcohol or drugs People who are at greatest risk include: Demographic o Youth o Female sex o Sexual minorities Social and Family Environment o Adverse childhood environment and experiences o Interpersonal difficulties in adolescence o Adverse life events o Social Isolation Psychological Factors/Situational factors o Mental health disorder (Depression, bipolar disorder) o Impulsivity, poor problem-solving Self-harm is more common than many people realize, especially among younger people. A survey of people aged 15-16 years carried out in the UK in 2002 estimated that more than 10% of girls and more than 3% of boys had self-harmed in the previous year. In most cases, people who self-harm do it to help them cope with unbearable and overwhelming emotional issues, caused by problems such as: social factors – being bullied, having difficulties at work or school, or having difficult relationships with friends or family trauma – physical or sexual abuse, or the death of a close family member or friend mental health conditions –depression, borderline personality disorder These issues can lead to a build-up of intense feelings of anger, hopelessness and self-hatred. Although some people who self-harm are at a high risk of ending their lives, many people who self-harm do not want to end their lives. In fact, the self-harm may help them cope with emotional distress so they don't feel the need to kill themselves. Detecting self-injurious behavior can be difficult. Cutters are usually secretive, and will hurt themselves in places that are easy to hide with clothing. Individuals who cut may also give excuses for their injuries, such as “the cat scratched me.” Over 1/3 of the respondents in a college study who reported cutting indicated that no one knew about the behavior. Here are some warning signs of cutting behaviors: o Unexplained burns, cuts, bruising, scars, healing or healed wounds, or similar o o o o o o o o markings on the skin—small, linear cuts are especially common Implausible stories that may explain one, but not all, of one’s physical injuries Consistently wearing long sleeves or pants, even when it’s hot outside Constantly wearing wristbands, large watchbands, or large bracelets Frequent bandages or other methods of covering wounds Odd or unexplainable paraphernalia, such as razor blades or needles Unwillingness to participate in activities that expose the body, such as swimming People often try to keep self-harm a secret because of shame or fear of discovery. For example, they may cover up their skin and avoid discussing the problem. It is often up to close family and friends to notice when somebody is selfharming, and to approach the subject with care and understanding. Self-harm does not always mean you want to end your life. You may self-harm to try and share how you are feeling, to try and feel better or to punish yourself. It is important to note that, individuals who self-harm are more likely to try to commit suicide than someone who does not self-injure. Sometimes, people try to take their own life as a way of how they feel or to control their emotions. In these situations this can be very similar to an act of self-harm. Mental health services can help with: o Practical help to deal with the situations that led or could lead to o your self-harm. o Help understanding the things that lead to your self-harm and why o you do it. o Seeing if you have any mental health problems. o Treatment of any mental health problems. o Problem solving therapy/ training. Perhaps someone you care about has told you that they self-harm or you have found out some other way. Here are some tips: o Don't take it personally: Self-harm is about the person, not about the people around them. Even if it feels like manipulation, it probably isn't. People do not harm themselves to be dramatic, annoy others, or to make a point. o Learn about self-harm: Get as much information about self-harm as you can. It will help you understand what the individual is going through. There are many books and websites which you can find details. o Be supportive: It is important that the person who self-harms knows that you will love them whether they self-harm or not. If possible, provide a safe place to talk. Set aside your personal feelings about self-harm and focus on what's really going on for the person. You should always be honest and realistic about what you can and can't do. Demands do not work: Demanding that someone stops selfharming (i.e. through punishing or guilt tripping the person) can often make the self-harm worse. It can make someone self-harm secretly. You may want to take things that they could use for selfharm away (for example, sharp knives). The pain of the person: Accepting and understanding that someone is in pain doesn't make the pain go away but can make the pain more bearable for the individual. Be hopeful about the possibilities of finding other ways of coping rather than self-harm. If they are willing, discuss possibilities for treatment with them but don’t push them into anything. Don't force things: Be patient. You might find it difficult if the person rejects you at first but they may need time to build trust. It is important to realize that cutting is rooted in emotional distress; it’s a way for some people to cope with their emotions or outside stressors. Cutting tends to become a compulsive behavior; it’s difficult for some people to stop even when they want to. As with other compulsions, professional help is often needed to stop the behavior. Treatment focuses on making people aware of the stressors that trigger cutting and on helping the individuals learn better means of coping. Treatment can also get to the bottom of the problems that are really bothering the person, and help him or her express their feelings in a more positive way. If you or someone you know is cutting or engaging in other types of self-injury, contact: Counseling Center Location: Gyte 5 Phone number: 219-989-2366 Website: www.purduecal.edu/counseling Offers free thearapeutic services to all currently enrolled students. Provided by HelpGuide.org General information about cutting and self-injury o About Self-Harm: Why You Self-Harm and How to Seek Help – Get the o o o o facts about cutting and self-injury. Learn what purpose it serves and how you can overcome it. (Mind) The Truth About Self-Harm (PDF) – In-depth guide for young people and their friends and families. Includes tips for talking about it and strategies for stopping self-harm. (Mental Health Foundation) Cutting – Article written for teens explains what cutting is, why people do it, how it starts, and where to go for help. (TeensHealth, Nemours Foundation) Self-Harm – Introduction to self-harm, including what makes people do it, danger signs, treatment, and things you can do to help yourself. (Royal College of Psychiatrists) Self-Harm and Trauma: Research Findings – Learn about the relationship between self-harm and childhood trauma and abuse. (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs) Self-help for cutting, self-injury, and self-harm How to Stop Hurting Yourself – Tips on ending self-harm from psychologist Tracy Alderman, author ofThe Scarred Soul: Understanding and Ending Self-Inflicted Violence. (self-injury.net) How Can I Stop Cutting? – Offers strategies for resisting the urge to cut by planning ahead, distracting yourself, and finding other ways to express your feelings. (TeensHealth, Nemours Foundation) Reducing and Stopping Self-Harm – Explore the reasons you want to stop injuring yourself, examine the reasons behind your behavior, and learn how to stop, as well as deal with slip-ups. (Scar Tissue) Coping Skills – Learn the coping skills that worked for one former self-injurer. Includes coping skills for staying in the present, for general wellness, and for replacing cutting. S.A.F.E. Alternatives (Self-Abuse Finally Ends) – Organization dedicated to helping people who self-harm. Includes treatment referrals, recovery information, and an information helpline: 1-800-366-8288. (S.A.F.E. Alternatives) Helping a friend or family member who self-harms o Family and Friends – Addresses the thoughts and feelings you may have about a loved one’s cutting or self-harm. Includes tips on what to do and what not to do. (self-injury.net) o Help for Families and Friends – Advice on how to talk to someone about their self-injury and how to be supportive without reinforcing the behavior. (Deb Martinson) Websites o Helpguide o SAFE self injury website o Lifesigns Skegg, K. (2005). Self-harm. The Lancet, 366(9495), 1471-1483. Evans, J. (2000). Interventions to reduce repetition of deliberate self-harm. Int rev psy, 33, 955958 Hawton, K., Kingsbury, S., Steinhardt, K., James, A., Fagg, J. (1999). Journal of Adolescence, 22, 369-378. Hawton, K, Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Weatherall, R. (2002). Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. Behavior Medical Journal, 325, 1207-1211. Isacsson, G. Richard, C.L. (2001). Management of patients who deliberately harm themselves. Behavioral Management Journal, 322, 213-215. Klonsky, E.D., Oltmans, T.F., Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 15011508. Nada-Raja, S., Morrison, D., & Skegg, K. (2003). A population-based study of help-seeking for self-harm in young adults. Australia New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 600-605. Nada-Raja, Skegg,K., Langley, J., Morrison, D., & Sowerby, P. (2004). Self-harmful behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. . Suicide Life Threatening Behevaior, 34, 177-186. Romans, S.E., Martin, J.L., Anderson, J.C., Herbison, G.P., & Mullen, P.E. (1995). Childhood adversity predicts earlier onset of major depression disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 3089-3096. Skegg, K., Nada-Raja, S., Dickson, N., Paul, C., & Williams, S. (2003) Sexual Orientation and self-harm in men and women . American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 541-546.