motivational interviewing in pediatric practice

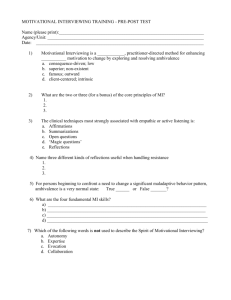

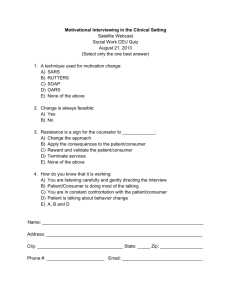

advertisement

Elizabeth Conway-Williams, M.A. William T. Dalton III, Ph.D. Doctoral Student Licensed Psychologist & Assistant Professor Assistant Director of Clinical Training Department of Psychology East Tennessee State University At the conclusion of this presentation you should be able to… Describe the characteristics of MI Understand the guiding principles of MI Understand the foundational clinical skills of MI Understand additional clinical tools for practice of MI Objectives will be met via… Lecture Video demonstrations Practice via case studies MI is a collaborative, person-centered form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation to change 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1980-1989 1990-1999 2000-2009 Lundahl & Burke (2009) summarized results of four meta-analyses on effectiveness of MI Effect sizes (Cohen’s D): Weak comparison groups (e.g., wait-list): 0.280.40 Strong comparison group (e.g., CBT or 12-step program): 0.04- 0.32 Suggest that MI is significantly better than no treatment and generally equal to other established treatments for a wide range of problems Alcohol-related problems Marijuana dependence Tobacco use Other drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin) Engaging clients in treatment Reducing risky behavior Increasing healthy behavior Asthma/COPD Brain Injury Cardiovascular Health/Hypertension Dentistry Diabetes Diet/Lipids Domestic Violence Dual Diagnosis Eating Disorders/Obesity Emergency Department/Trauma/ Injury Prevention Family/Relationships Gambling Health Promotion /Exercise/Fitness HIV/AIDS Medical Adherence Mental Health Offenders Pain Parenting Interventions Reproductive Health Sexual Behavior Speech/Vocal Therapy Motivational Interviewing Professional Training DVD (1998) Interview With Founders William Miller, Ph.D. (Clinical Psychology) Stephen Rollnick, Ph.D. (Clinical Psychology) Motivation was once considered a trait or ingrained quality MI was first described in 1983 to help motivate drinkers to change behavior (resistance) Ambivalence was being considered a normal and defining state and the recognition that change is not usually made without inconvenience Around the same period the trans-theoretical model of stages of change was being proposed Precontemplation Contemplation Preparation Action Maintenance Recognizes behavior change as a process Individuals are considered to be in different stages of behavior change Assists individuals in moving through stages via a combination of a strong patientprovider relationship and specific techniques that encourage patients to discuss the possibility of behavior change Directive Client-centered Honors autonomy Counseling style Resolve ambivalence Evocative Collaborative Minimizes resistance Offers acceptance Arguing that a person has a problem and needs to change Offering advice without the patient’s permission Doing most of the talking Simply giving a “prescription” A quick trick or simple procedure Resisting the Righting Reflex Roll with resistance Understand Develop discrepancy Listen To Your Patient Express empathy Empower Your Patients Motivations Your Patient Support self-efficacy Open-ended questions Affirmations Reflective listening Summarizing Open-ended questions Questions that encourage patients to elaborate, feel respected, and elicit change talk Examples “Would you tell me more about ____?” “How does smoking fit with your dreams of becoming a pro basketball player?” “How does your current weight interfere with the activities you most enjoy?” “In what ways is your diabetes a problem for you?” “How have you overcome other obstacles in the past?” Open-ended questions Avoid questions that can be answered yes/no Examples “Did you ____?” “Will you ____?” “Can you ____?” “How many ____?” Affirmations Statements reinforcing positive choices, strengths, and self-efficacy Examples “Coming in every week for therapy and doing homework is really tough. You are handling a difficult treatment protocol really well.” “I’m impressed with how mature you are.” “Absolutely! It is really tough to do all that you need to do when you’re not feeling well. And sticking to your diet makes it easier for you to do your chores, complete your homework, and hang out with your friends.” Reflective listening Following along by restating what is said, clarifying, adding meaning, or highlighting emotions Examples “It sounds like you are feeling ____.” “It appears that you see no real problem with your current drinking.” “On the one hand your family really enjoys several hours of television each day and on the other hand you find that it is interfering with your family’s ability to be physically active which you also enjoy and find important.” Summarizing Sum up patients stories, add insight and reinforce statements in favor of change Examples “It’s important for you to fit in with your friends. Sometimes adhering to your chest physiotherapy regimen makes that tough.” “On the other hand, when you don’t adhere to your therapy, you notice that you don’t feel as well. And when you don’t feel as well, it’s even harder for you to keep up with the energy of your friends. Is there anything that you want to add that I may have missed?” Setting an agenda Assessing readiness to change Developing discrepancy Pros/cons Values and current behavior Ask permission to discuss a specific topic “Would you be willing to spend a few minutes discussing your drinking?” “Are you interested in discussing ways to better take your medicine?” Ask patient to name an area of concern with the help of a menu of options “There are several topics we could discuss related to your health. For example, taking your medicine, eating patterns, amount of physical activity or time spent watching television, smoking or drinking behavior, sexual activity, or even others. What is of most concern to you?” Use Two useful tools for assessing and enhancing patient readiness for health behavior changes are the Importance and Confidence Rulers Both on a 11-point scale of Rulers and Scaling 0 = least importance or confidence 10 = most importance or confidence Scaling or follow-up questions may be used to facilitate change talk “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being ‘very important,’ how important is it for you to decrease your drinking?” Reflect patient’s answer “You chose _____.” Ask follow-up questions “Why did you not choose a lower number?” “Why did you not choose a higher number?” “What would it take to move to an _____?” “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being ‘very confident,’ assuming you decided to drink less, how confident are you that you could succeed?” Reflect patient’s answer “You chose _____.” Ask follow-up questions “Why did you not choose a lower number?” “Why did you not choose a higher number?” “What would it take to move to an _____?” Allows patients to list the pros and cons of changing or of not changing health-related behaviors , and then to assign subjective weights (of importance) to each “Tell me some good and not so good things about taking your medicine.” “Let’s list together and discuss the pros and cons of completing your homework. Afterwards, let’s list together and discuss the pros and cons of not completing your homework.” Values for You Good parent Responsible Disciplined Good spouse Respected at home On top of things Spiritual Others: ____ Values for Your Family Cohesive Healthy Peaceful meals Getting along Spending time together Others: ____ What do you value most? How does your/your child’s/family’s current lifestyle fit in with that? “On the one hand you value a healthy family and on the other hand you and your child have excess weight and you report that your diets are poor?” “So where does that leave you?” Characteristics Guiding Principles Resisting the righting reflex Understand your patients motivations Listen to your patient Empower your patient Foundational Clinical Skills Open-ended questions Affirmations Reflective listening Summarizing Additional Clinical Tools Review case studies Case 1 Case 2 Turn to your neighbor Develop a plan Stage of change? Goals? What foundational clinical skills would you emphasize? Which additional clinical tools may you use? Role-play Divide into groups of 3 between group members One person patient One person health care provider One person evaluator Patient reviews script Health care provider practices foundational clinical skills (OARS) and at least 1 additional clinical tool (i.e., Assessing readiness to change, Pros/cons, or Values and current behavior) Evaluator monitors progress and provides feedback Barlow, S. E., & the Expert Committee. (2007). Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics, 120 (Suppl. 4), 164-192. Erickson, S. J., Gerstle, M., & Feldstein, S. W. (2005). Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 1173-1180. Glynn, L. H., & Levensky, E. R. (2009). Promoting treatment adherence using motivational interviewing: Guidelines and tools. In L. C. James & W. T. O’Donohue (Eds.), The primary care toolkit: Practical resources for the integrated behavioral care provider (pp. 199-231). New York: Springer. Lundahl, B., & Burke, B. L. (2009). The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: A practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(11), 1232-1245. Lundahl, B. W., Kunz, C., Brownell, C., Tollefson, D., & Burke, B. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137-160. Resnicow, K., Davis, R., Rollnick, S. (2006). Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: Conceptual issues and evidence review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 106, 2024-2033. Rollnick, S., Heather, N., & Bell, A. (1992). Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. Journal of Mental Health, 1, 25-37. Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: The Guilford Press. Miller, W., & Rose, G. (2009). Towards a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist, 64, 527-537. Rollnick, S., Miller, W. R., & Butler, C. C. (1999). Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. New York: Churchill Livingston. Rollnick, S., Miller, W. R., & Butler, C. C. (2008). Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: The Guilford Press. Sindelar, H. A., Abrantes, A. M., Hart, C., Lewander, W., & Spirito, A. (2004). Motivational interviewing in pediatric practice. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 34, 322-339. Motivational Interviewing: Resources for Clinicians, Researchers, and Trainers http://www.motivationalinterview.org/