Nasopharyngolaryngoscopy for Family Physicians

advertisement

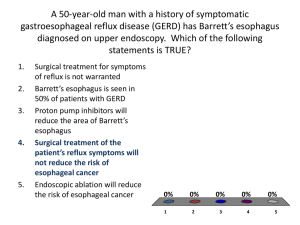

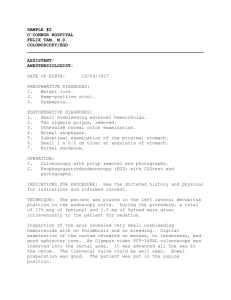

EGD for Family Physicians Scott M. Strayer, MD, MPH Assistant Professor University of Virginia Health System Department of Family Medicine Case Presentation A 47-year-old female presents with a long standing history of heartburn and epigastric tenderness. There is no family history of stomach cancer, and she is tried on a 2-month trial of PPI with significant relief, but fails an attempt to stop the therapy. Barrett’s Esophagus Background Performed by about 4% of Family Physicians (Source: American Academy of Family Physicians, Practice Profile II Survey, May 2000). EGD performed by primary care physicians was associated with enhanced management or improved diagnostic accuracy in 89% of cases (Rodney WM et al: Esophagogastroduodensocopy by family physicians--Phase II: a national multisite study of 2500 procedures. Fam Pract Res J 13(2):121, 1993). Background FP series showed an 83% correlation between pathologic diagnoses of directed biopsies and endoscopic diagnoses including 4 cases of confirmed cancer (this was comparable to subspecialist’s rates). (Woodliff DM. The role of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1979;8:715-9). Complication Rates Among FP’s In this same series, no complications occurred in 1,783 EGD’s performed by 13 FP’s. Another series found one complication in 717 procedures (Deutchman ME, Connor PD, Hahn RG, Rodney WM. Diagnostic and therapeutic tools for the family physician's office of the 21st century. Fam Pract Res J. 992;12:147-55). AAFP’s Position 1. Gastrointestinal endoscopy should be performed by physicians with documented training and/or experience, and demonstrated competence in the procedures. 2. Training in endoscopy includes clinical indications, diagnostic problem solving, mechanical skills acquired under direct supervision and prevention and management of complications. 3. Endoscopic competence is determined and verified by evaluation of performance under clinical conditions rather than by an arbitrary number of procedures. AAFP Position 4. Endoscopic competence should be demonstrated by any physician seeking privileges for the procedure. 5. Privileges should be granted for each specific procedure for which training has been documented and competence verified. The ability to perform any one endoscopic procedure does not guarantee competency to perform others. 6. Endoscopic privileges should be defined by the institution granting privileges and reviewed periodically with due consideration for performance and continuing education. Clinical Indications Cancer surveillance in high-risk patients (e.g. Barrett’s esophagus, Menetrier’s disease, polyposis, pernicious anemia). Esophageal stricture Gastric retention Chronic duodenitis Chronic esophagitis Chronic gastritis Symptomatic hiatal hernia Gastric ulcer monitoring Clinical Indications Chronic peptic ulcer disease Pyloroduodenal stenosis Varices Angiodysplasia in other bowel areas Abdominal mass Unexplained anemia Gross or occult GI bleeding X-ray abnormality on upper GI study Clinical Indications Dyspepsia Dysphagia/odynophagia Early satiety Epigastric pain Food sticking Meal-related heartburn Severe indigestion Chronic nausea or vomitting Substernal or paraxiphoid pain Reflux of food Severe weight loss Clinical Indications Not improving after 10 days of H2-blocker or PPI therapy, or not resolving after 4-6 weeks of H2-blocker of PPI therapy, where appropriate. Contraindications History of bleeding disorder (platelet dysfunction, hemophilia) History of bleeding esophageal varices Cardiopulmonary instability Suspected perforated viscus Uncooperative patient Equipment Video gastroscope Light source Camera source Color video Video Monitor Video recorder Biopsy forceps Williams oral introducer Endoscopy table Equipment Stool with wheels for endoscopist Sphygmomanometer Stethoscope ECG machine or cardiac monitor Pulse oximeter IV fluids Suction equipment and tubing Specimen jars with formalin solution Syringes and needles Equipment Rubber gloves CLO test materials Anesthetic, sedative, and narcotic medications Oxygen and delivery mask Crash cart supplies Cleaning supplies Antibiotic Prophylaxis With or without biopsy, is not recommended according to AHA guidelines (1997). High Risk Patients Greater than 70 years old Less than 12 years old Agitated, uncooperative patient History of angina History of significant aortic stenosis History of significant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease History of cerebrovascular accident Presence of significant bleeding disorder or coagulopathy Barium administration within a few hours of procedure Contraindications for VASC Procedures Weight greater than 350 lbs. Significant COPD or pulmonary disease requiring 02 Sleep apnea requiring CPAP Renal Failure on dialysis Hepatic failure Increased Goldman’s risk (i.e. MI within 6 months, unstable angina, etc.) Preparation Discontinue ASA/NSAIDS 7 days prior to examination. NPO 7pm evening before procedure (at least 8 hours NPO). Examine oral cavity, remove dentures. Can use simethicone pre-procedure or as needed. Preparation Place the patient in the left lateral recumbent position. Spray the back of the throat with 2% lidocaine or swallow viscous lidocaine (30cc). Place Williams introducer in patient’s mouth over the tongue and into the oral pharynx. Inser the lubricated tip of the endoscope down the introducer, and slowly advance to the point of first resistance (about 15-17 cm). This is the location of the vocal cords and cricopharyngeus muscle. Vocal Cords Intubating the esophagus Ask the patient to swallow repeatedly until a feeling of “give” is obtained; at this point, the endoscope can then be passed naturally into the esophagus. NOTE: NEVER USE FORCE AT ANY TIME, Let the natural swallowing mechanism advance the scope. Esophagus Where are We? Visualizing the Esophagus Insufflate just enough air to dilate the esophagus and visualize the mucosa. Gently advance down the esophagus. The first landmark will be the bronchoaortic constriction. Try to visualize on entering because mucosa may be irritated by passage of the scope. Landmarks Squamocolumnar Junction Continue to the squamocolumnar junction between the esophagus and the stomach, which is approximately 40cm from the patient’s teeth. Mucosal coloration changes from pale to dark pink. This boundary is known as the Z line. Squamocolumnar junction Stomach After passing the GE-junction, the endoscope will enter the stomach. The gastric lake and rugae become visible. Follow the rugae to the angularis, antrum and pre-pyloric areas. Gastric Rugae Angularis and Closed Pylorus Antrum and Pyloric Opening Entering the Duodenum Guide the endoscope through the relaxed pyloric sphincter and into the duodenal bulb. Ampulla of Vater may be visualized. Duodenum Retroflexion Withdraw past the pyloric sphincter into the antrum. Turn the large wheel 180 degrees so that the scope is looking back on itself. Slowly withdraw so that the GE junction can be clearly seen and examine the adjacent cardia. Look for fixed or sliding hiatal hernia. Retroflexion GE Junction Finishing the Procedure Straighten the endoscope by rotating the wheel back to the original position. Slowly withdraw the endoscope through the esophagogastric junction and back through the esophagus. Examine the vocal cords as the instrument is withdrawn. Sending the Patient Home The anesthesiologist or assistant should complete the monitoring process. The physician should reexamine the patient prior to discharge from the facility. A 30-minute observation period is generally sufficient, especially if minimal sedation is used. No food or drink for approximately 30 minutes post-procedure due to local anaesthetic.