Shakespeare

advertisement

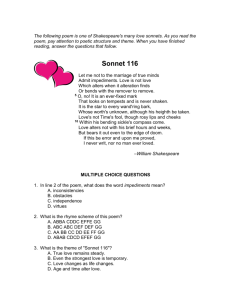

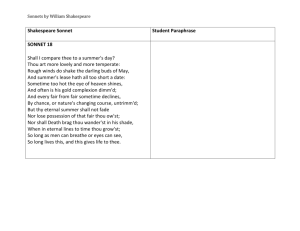

Adam Smith Mrs. Shriver AP English 12 15 Wed. 2012 Meditations on Love Shakespeare, it would seem, has a lot to say about love. Over the course of his one hundred fifty-six sonnets, he uses the word no less than 233 times. But while the subject is common, the ways he addresses it are certainly not. Sonnets 29 and 116 are ideal examples. Both celebrate the power of love in 14 short lines, but neither goes about it in a similar way. While their similarities are clear and undeniable, what really makes these sonnets‒ and their author‒ shine are the two divergent but nonetheless classic approaches they take to conquer the enigmatic issue at hand: love. For an immortal love poem, sonnet 29 certainly does not begin as one might expect. Even from the first sentence, “When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes/I all alone beweep my outcast state,” the poem exhibits a melancholy atmosphere. The enjambment in these first stanzas imitates the breathless cry of an unheard plea or the lengthy, uninhibited cadence of a mournful dirge. The jarring harshness of the rhythm (best exhibited in syllables like “-ble,” “deaf,” “Heav-,“ and “Boot-,” urgently thrown against each other) and expertly wretched diction (disgrace, beweep, deaf, Heaven, bootless) both contribute to the outcast desperate atmosphere. Throughout the 2nd quatrain, Shakespeare extends this dark theme. The diction remains tormented as the poet fruitlessly yearns to escape his circumstances, wishing alternately for another man’s skill or opportunity to replace his own. In multiple instances, Shakespeare uses parallel structure (lines 6: “like him,” and line 7: “desiring this man’s, that man’s”). This can be seen as an effort to structurally reinforce a thematic notion: that this depression is not an isolated event but a common occurrence; just as parallel phrases recur, so do the poet’s envious yearnings. A major volta arises in the 3rd quatrain. After establishing all the downtrodden imagery and connotation of the first octave, Shakespeare remarks that in such times, he thinks of his love. This is where the heart of the poem, its theme, is made apparent. He makes in clear that he not only thinks of his lover, but also rejoices her. As homage to the transformative power of love, the first and only simile of the poem is invoked: “like a lark at break of day arising.” When he imagines his love, Shakespeare gushes, he is free, and the world’s beauty is made clear. The final rhyming couplet draws everything beautifully together: the poet’s love makes him wealthy beyond the rivalry of kings. An interesting final note to make is that in this last line, the word state is used for the third time in the sonnet. Looking back, one finds that each progressive time it appears, the connotation becomes a shade lighter. In this final stanza, the word stands fully liberated, serving to reinforce the beautiful theme of the poem while at the same time tying all parts of it together. While the topic of love is shared by both 29 and 116, sonnet 116 takes a much different approach to the issue. This work is a far more idealistic, traditional illustration of what makes love love. It is a telling sign that this sonnet uses the word alter (through various polyptonic modes) thrice, every time with the qualifier not attached. This is markedly different from Shakespeare’s earlier treatment of state. Whereas before, the word altered meaning throughout the sonnet, here, the word remains steadfastly loyal to a single meaning. This is aligned perfectly with the theme of the poem itself, which insists that constancy above all is vital for love. Shakespeare reflects this theme in a number of other ways as well. In lines three and four, he utilizes parallelism (in conjunction with polypton) to create a repetitious effect. This is an example of content and structure enhancing each other; as love refuses to alter, so do his words. The poet compares love to a lighthouse and a star, both symbols of steadfast guidance. Even upon the introduction of death personified, the concept of love in the poem endures to infinity. The volta, if one exists, occurs at the rhyming couplet. Here, Shakespeare directly addresses his readers, saying that if he can be proven wrong and that what he has described is not love, than no one had ever loved, and he might as well have never written. While this may reflect a small change in the attitude of the sonnet, it is not nearly as drastic as the volta of 29. In a way, this makes 116 feel more resolute‒ exactly like the love it describes. While these two poems exhibit different takes on the same topic, both are extremely poetically sound. Shakespeare went to great lengths to reinforce each sonnet’s theme with appropriate linguistic and structural detailing. The expertise with which these poetic techniques are employed almost gives these poems an even grander connecting thread. Yes, they both discuss love, but more importantly, they do it with such effective flourish that one need not even agree with their assessments to appreciate their total mastery of the sonnet form.