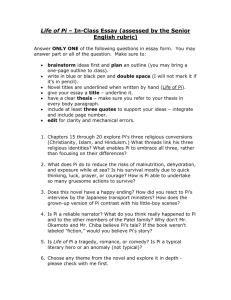

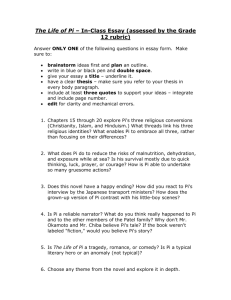

Advanced Placement English Literature 12

advertisement

WELCOME TO Advanced Placement English Literature 12 PLAYING THE MUSIC.... OR HOW TO BECOME AN AP GROUPIE The AP English Literature/Composition course is all about independence and learning, not rote memory and schoolwork. According to the Teacher’s Guide to Advanced Placement Courses in English Literature and Composition, a difference exists between learning and schoolwork: “Schools generate schoolwork the way bureaucracies generate paperwork. Schoolwork is pop quizzes, percentage points, vocabulary lists, matching, fill-in the-blanks, detention, Cliff Notes, a paragraph due Monday, a test on summer reading, 10-point penalties...grading on a curve, raising your hand before you answer, and finding the dramatic climax of Macbeth. Nothing is necessarily wrong with any particular item of schoolwork, just as nothing is wrong with any particular rain shower, but one would no more want a climate of nothing but schoolwork than one would want a climate of nothing but rain. In an AP Literature and Composition class composed of capable, motivated students and a teacher who loves literature, there is a fair chance of shifting the emphasis from schoolwork to learning.” This learning and independence cannot spring from a lecture in which I am in the active mode telling you what I think a piece of literature means and you are in a passive, captive-audience mode soaking up my ideas. I am doing you a disservice if I decide what topics you will discuss and write about and what new discoveries you will make. The Teacher’s Guide goes on to say, “it is more important that students learn to read books that they have not yet opened than to learn the standard and accepted interpretations of the texts of the course. If students are learning to read independently, teachers will entertain topics that students find central, and students will ask as many questions as teachers.” We won’t be able to achieve this ideal learning situation without a commitment from all parties involved. I have committed myself to researching the best strategies for the class and choosing the finest pieces of literature available for study. I’ll provide the framework and act as a resource for you to turn to for help. You must commit yourselves to reading, thinking, discussing, and writing with depth and maturity. In other words, you’ll provide the true heart of the course. If your brain is locked in summer gear, try this analogy for levels of commitment: Level 1: You tune in to a radio station...you like the song that’s playing, and you listen until it’s over. Level 2: You hum along with song, tapping your foot. Level 3: You go out and buy the album. Level 4: You go to all this band’s concerts, buy the t-shirt, hang up posters on your wall, maybe even take drum lessons to emulate (an AP word) them. Level 5: You become a groupie, or maybe even beyond by trying out for the band or forming your own group and playing the music yourself. Your grade in AP English Literature 12 will ultimately depend on how you react to the “music” playing on the radio. If you station surf...working on other subjects during class, not turning in work; or if you limit yourself to humming...completing only a portion of assigned reading or writing, turning in late assignments ~~~ don’t expect to be a success in the class. However, if you decide to play the music yourself...reading, analyzing, formulating, evaluating, writing, meeting deadlines ~~~ you can expect not only a stellar grade in AP English Literature12, but also a strong foundation for your college endeavors. Some Summer Programming Notes: So that we can begin the year with an in-depth discussion of a novel of literary merit, I’m asking you to read one book this summer and submit required assignments to me by Monday, August 8th, 2011. Please remember that since AP English Literature12 is patterned as a college level course, we’ll examine college level novels and plays. One of the purposes of this course is to broaden our understanding and appreciation of both classic and contemporary literature. We don’t always read this literature for pure enjoyment, but for exposure to ideas, styles of writers, differing opinions, and thought-provoking situations. While some of the texts, especially contemporary selections, deal with controversial issues / topics, the titles are suggested by the Advanced Placement Program because of their overall themes, impressive style, and literary merit. Many of the selections that we study during the year are on university recommended reading lists. I choose the summer reading selections from contemporary titles that have either appeared on the AP English Literature Exam, been nominated for literary prizes, won the prizes, and/or have been suggested by a variety of knowledgeable sources: other AP English teachers on a list-serve I subscribe to, the American Library Association, our CPHS librarian. The choices for this summer are: No Country for Old Men by Cormac McCarthy “Mr. McCarthy's story is so exquisitely harrowing that the reader can forget to breathe." — Bryan Woolley, Dallas Morning News Seven years after Cities of the Plain brought his acclaimed Border Trilogy to a close, McCarthy returns with a mesmerizing modern-day western. In 1980 southwest Texas, Llewelyn Moss, hunting antelope near the Rio Grande, stumbles across several dead men, a bunch of heroin and $2.4 million in cash. The bulk of the novel is a gripping man-on-the-run sequence relayed in terse, masterful prose as Moss, who's taken the money, tries to evade Wells, an ex–Special Forces agent employed by a powerful cartel, and Chigurh, an icy psychopathic murderer armed with a cattle gun and a dangerous philosophy of justice. Also concerned about Moss's whereabouts is Sheriff Bell, an aging lawman struggling with his sense that there's a new breed of man (embodied in Chigurh) whose destructive power he simply cannot match. In a series of thoughtful first-person passages interspersed throughout, Sheriff Bell laments the changing world, wrestles with an uncomfortable memory from his service in WWII and—a soft ray of light in a book so steeped in bloodshed—rejoices in the great good fortune of his marriage. While the action of the novel thrills, it's the sensitivity and wisdom of Sheriff Bell that makes the book a profound meditation on the battle between good and evil and the roles choice and chance play in the shaping of a life. Room by Emma Donoghue Emma Donoghue’s remarkable new novel, Room, is built on two intense constraints: the limited point of view of the narrator, a 5-year-old boy named Jack; and the confines of Jack’s physical world, an 11-by-11foot room where he lives with his mother. We enter the book strongly planted within these restrictions. We know only what Jack knows, and the drama is immediate, as is our sense of disorientation over why these characters are in this place. Jack seems happily ensconced in a routine that is deeply secure, in a setting where he can see his mother all day, at any moment. She has created a structured, lively regimen for him, including exercise, singing and reading. The main objects in the room are given capital letters — Rug, Bed, Wall — a wonderful choice, because to Jack, they are named beings. In a world where the only other companion is his mother, Bed is his friend as much as anything else. Jack, in this way, is a heightened version of a regular kid, bringing boundless wonder and meaning to his every pursuit. Donoghue navigates beautifully around these limitations. Jack’s voice is one of the pure triumphs of the novel: in him, she has invented a child narrator who is one of the most engaging in years — his voice so pervasive I could hear him chatting away during the day when I wasn’t reading the book. Donoghue rearranges language to evoke the sweetness of a child’s learning without making him coy or overly darling; Jack is lovable simply because he is lovable. Through dialogue and smartly crafted hints of eavesdropping, Donoghue fills us in on Jack’s world without heavy hands or clunky exposition. The reader learns as Jack learns, and often we learn more than he can yet grasp, but as with most books narrated by children, the gap between his understanding and ours is a territory of emotional power. When I finished this book I was lying in a bath (a tepid bath by then). I closed it, and then sat and looked at the cover of this book. Then I turned and looked at the back for a little while, before eventually putting it down. This book can do that to you. You need to have a little moment alone after you have finished reading it. It was a disturbing and totally unique book. Some reviewers have claimed they can’t compare this book to any other and I see why they have said this. It is certainly being nominated for awards left, right and centre, was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and has already won the Hughes and Hughes Irish Novel of the Year and the Rogers Writers Trust Fiction Prize. The Echo Maker by Richard Powers On a winter night on a remote Nebraska road, 27-year-old Mark Schluter flips his truck in a near-fatal accident. His older sister Karin, his only near kin, returns reluctantly to their hometown to nurse Mark back from a traumatic head injury. But when he emerges from a protracted coma, Mark believes that this woman — who looks, acts, and sounds just like his sister — is really an identical impostor. Shattered by her brother's refusal to recognize her, Karin contacts the cognitive neurologist Gerald Weber, famous for his case histories describing the infinitely bizarre worlds of brain disorder. Weber recognizes Mark as a rare case of Capgras Syndrome, a doubling delusion, and eagerly investigates. What he discovers in Mark slowly undermines even his own sense of being. Meanwhile, Mark, armed only with a note left by an anonymous witness, attempts to learn what happened the night of his inexplicable accident. The truth of that evening will change the lives of all three beyond recognition. Set against the Platte River's massive spring migrations — one of the greatest spectacles in nature — The Echo Maker is a gripping mystery that explores the improvised human self and the even more precarious brain that splits us from and joins us to the rest of creation. The Painted Drum by Louise Erdrich Haunted and haunting, Louise Erdrich's 10th novel navigates smoothly back and forth across the border that separates the living from the dead. Beginning in 1984 with her first novel, Love Medicine , and continuing through many volumes that developed the histories and fates of recurring characters, she has frequently described the ghostly tug of the dead on the people they leave behind. But never more explicitly than in this new book has she made so fluid a connection between the two worlds. Once again employing the technique of alternating voices that worked so successfully in her previous novels, Erdrich tells three intertwined stories in The Painted Drum from the perspectives of several characters. Faye Travers, the introductory narrator, lives with her mother in a small New Hampshire town where the two women have developed a successful business. Dealing unsentimentally in "the stuff of life, or more precisely, the afterlife of stuff," Faye and her mother organize and sell dead people's valuables, with a specialty in Native American artifacts. Like Erdrich's, Faye's ancestry is part European and part Ojibwe, or Chippewa, and when she inspects the estate of a recently deceased neighbor whose grandfather was an Indian agent at the reservation in North Dakota where Faye's own grandmother was born, she discovers an object that seems to throb with spiritual energy. It's a painted drum, huge and lavishly embellished and so dazzling that Faye, despite being thoroughly assimilated and unemotional about her heritage, is compelled to steal it. Drums, she later learns, are considered by the Ojibwe to be living things, "made for serious reasons by people who dream the details of their construction." Drums have the power to cure or kill, and they speak to one another. They must be offered food and tobacco and should never be placed on the ground or left alone. The drum that Faye steals, moreover, is a conduit between the living and the spirit world -- particularly, for special reasons, the spirits of little girls. I suggest that you buy your own copy of the novel you choose to read because you’ll need it for an extended period of time. Try the used bookstores first; they usually charge half the cover price. If you have Internet access, you should try these three bookstores online: Amazon Books (www.amazon.com), or Powell’s Books (www.powells.com). EBay might also have copies of these titles if you enjoy the “thrill” of auctions. I bought all these titles online and paid only a fraction of the retail price. If you can’t purchase your own copy, try requesting the title from Tulsa City-County Library…either Page or Pratt. I’ll ask them to have copies of each novel on reserve available on a first-come, first-served basis. NOTE: As you read your novel, use some method of recording your thoughts / feelings / observations / questions about what’s going on and specific passages that you find memorable or confusing. Look for rhetorical strategies and literary devices…specific examples of the resources of language that the author uses: imagery, metaphor, simile, paradox, irony (three types: situational, dramatic, and verbal), allusion, analogy, oxymoron, pun, personification. If you don’t use some way of tracking your thoughts this summer, our discussions at the beginning of the year won’t be as focused. Take this step for yourself, not for a grade. Also, mark memorable passages as you read. We’ll have a “Quaker Reading” during the first week of school: we’ll share passages from all four novels with the class. When you finish reading the novel, complete these three assignments (for yourself AND for a grade): 1. Have someone take a picture of you reading your summer novel in some unique place and send it with your assignment; we’ll make a bulletin board collage of pictures when school starts. 2. Write a letter explaining what you thought of the novel. Using your post-it notes or Writer’s Notebook, list some topics / questions that you would like to discuss. List some favorite passages and why you like them or vice-versa. It’s your job to prove to me that you’ve read the novel, not make me suspect that you haven’t. In addition, introduce yourself…tell me a little about you, your family, interests. This letter need not be typed. 3. Find a poem that in some way relates to the novel that you read. Type the poem, list the author and the source, then discuss how it mirrors the novel, referring to specifics from both selections. You will find that I am allergic to generic commentary; your grade will suffer if my eyes start itching and my nose runs as I read your analysis. 4. Write an essay of approximately two pages (or more) typed, double-spaced, using one of the writing prompts below taken from past AP English exams. Be sure that you use specific details and passages from the novel you read to back up your position and make sure that you address all parts of the prompt. Use page numbers when quoting direct passages from the novel. I know that it’s summer and your brain is for the most part on vacation…try your best to make your essay effective…but also keep in mind you’ll have a chance to revise it before receiving a final score. A. In great literature, no scene of violence exists for its own sake. In a well-organized essay, explain how a scene or scenes of violence contribute to the meaning of the complete work. Avoid plot summary. (1982) B. Novels sometimes depict a conflict between a parent (or parental figure) and a son or daughter. Write an essay in which you analyze the sources of the conflict and explain how the conflict contributes to the meaning of the work. (1990) C. The eighteenth-century British novelist Laurence Stern wrote, “no body, but he who has felt it, can conceive what a plaguing thing it is to have a man’s mind torn asunder by two projects of equal strength, both obstinately pulling in a contrary direction at the same time.” From a novel or play choose a character (not necessarily the protagonist) whose mind is pulled in conflicting directions by two compelling desires, ambitions, obligations, or influences. Then, in a well-organized essay, identify each of the two conflicting forces and explain how this conflict within one character illuminates the meaning of the work as a whole. (1999) D. One definition of madness is “mental delusion or eccentric behavior arising from it.” But Emily Dickinson wrote: “Much madness is divinest Sense – To a discerning eye – “ Novelists and playwrights have often seen madness with a “discerning Eye.” Select a novel or play in which a character’s apparent madness or irrational behavior plays an important role. Then write a well-organized essay in which you explain what this delusion or eccentric behavior consists of and how it might be judged reasonable. Explain the significance of the “madness” to the work as a whole. Do not merely summarize the plot. (2001) E. Some novels and plays seem to advocate changes in social or political attitudes or in traditions. Note briefly the particular attitudes or traditions that the author wishes to modify. Then analyze the techniques the author uses to influence the reader's or audience's views. Avoid plot summary. (1987) F. The conflict created when the will of an individual opposes the will of the majority is the recurring theme of many novels, plays and essays. Select a fictional character who is in opposition to his or her society. In a critical essay, analyze the conflict and discuss the moral and ethical implications for both the individual and the society. Do not summarize the plot or action of the work you choose. (1976) G. An effective literary work does not merely stop or cease; it concludes. In the view of some critics, a work that does not provide the pleasure of significant closure has terminated with an artistic fault. A satisfactory ending is not, however, always conclusive in every sense; significant closure may require the reader to abide with or adjust to ambiguity and uncertainty. In an essay, discuss the ending of your novel. Explain precisely how and why the ending appropriately or inappropriately concludes the work. Do not merely summarize the plot. (1973) H. Writers often highlight the values of a culture or a society by using characters who are alienated from that culture or society because of gender, race, class, or creed. Show how that character’s alienation reveals the surrounding society’s assumptions and moral values. (1995) I. In some works of literature, a character who appears briefly, or does not appear at all, is a significant presence. Write an essay in which you show how such a character functions in the work. You may wish to discuss how the character affects action, theme, or the development of other characters. (1994) J. Critic Roland Barthes once said, “Literature is the question minus the answer.” Considering Barthes’ observation, write an essay in which you analyze a central question the work raises and the extent to which it offers any answers. Explain how the author’s treatment of the question affects your understanding of the work as a whole. (2004) K. Some works of literature use the element of time in a distinct way. The chronological sequence of events may be altered, or time may be suspended or accelerated. Show how the author’s manipulation of time contributes to the work as a whole. (1986) L. In Kate Chopin's The Awakening (1899), protagonist Edna Pontellier is said to possess "that outward existence which conforms, the inward life which questions." In a novel or play that you have studied, identify a character who conforms outwardly while questioning inwardly. Then write an essay in which you analyze how this tension between outward conformity and inward questioning contributes to the meaning of the work. Avoid mere plot summary. (2005) M. In many works of literature, past events can affect, positively or negatively, the present actions, attitudes, or values of a character. Choose a novel or play in which a character must contend with some aspect of the past, either personal or societal. Then write an essay in which you show how the character’s relationship to the past contributes to the novel as a whole. Do not merely summarize the plot. (2007) N. In a literary work a minor character, often known as a foil, possesses traits that emphasize, by contrast or comparison, the distinctive characteristics and qualities of the main character. For example, the ideas or behavior of the minor character might be used to highlight the weaknesses or strengths of the main character. Choose a novel or a play in which a minor character serves as a foil to a main character. Then write an essay in which you analyze how the relationship between the minor character and the major character illuminates the meaning of the work. (2008) O. A symbol is an object, action, or event that represents something or that creates a range of associations beyond itself. In literary works a symbol can express an idea, clarify meaning, or enlarge literal meaning. Select a novel or play and, focusing on one symbol, write an essay analyzing how that symbol functions in the work and what it reveals about the characters or themes of the work as a whole. Do not merely summarize the plot. (2009) P. Palestinian American literary theorist and cultural critic Edward Said has written that “Exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience. It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.” Yet Said has also said that exile can become “a potent, even enriching” experience. Select a novel, play, or epic in which a character experiences such a rift and becomes cut off from “home,” whether that home is the character’s birthplace, family, homeland, or other special place. Then write an essay in which you analyze how the character’s experience with exile is both alienating and enriching, and how this experience illuminates the meaning of the work as a whole. You may choose a work from the list below or one of comparable literary merit. Do not merely summarize the plot. (2010) Q. In a novel by William Styron, a father tells his son that life “is a search for justice.” Choose a character who responds in some significant way to justice or injustice. Then write a welldeveloped essay in which you analyze the character’s understanding of justice, the degree to which the character’s search for justice is successful, and the significance of this search to the work as a whole. Your picture, letter, poem / explanation, and essay must be postmarked or dropped off at my house, 1201 N. Garfield Ave, Sand Springs, OK 74063-7322 on or before Monday, August 8th. I’ll be organizing literature circles for each class, so SEND ME YOUR ASSIGNMENTS ON TIME. Our first major projects will revolve around these novels, so don’t jeopardize your grade in the class by neglecting to complete the reading and the required work. If you have any questions about the summer reading assignment, call me at 245-0898 (home) or 406-7823 (cell). You can also e-mail me at shereek.baker@gmail.com or sheree.baker@sandites.org. If you would like to discuss the novel as you read, please visit our class website at cphsbaker.com to participate in the discussion threads over each novel. Even if you don’t have Internet access at home, you could go to the library to post comments. Have a great summer…I’m looking forward to our AP English Literature class next year. Sincerely, Sheree Baker