Running head: ANALYZING FIELDNOTES ANALYZING

advertisement

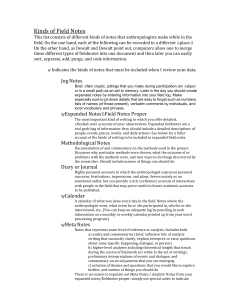

Running head: ANALYZING FIELDNOTES Forthcoming, IN: Edward Elgar Handbook of Qualitative Research in Education Analyzing Fieldnotes: A Practical Guide Zoё Corwin & Randall F. Clemens Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis University of Southern California 3470 Trousdale Parkway, WPH 701D Los Angeles, CA 90089 (213) 740-7218 zcorwin@usc.edu rclemens@usc.edu 1 ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 2 Zoë B. Corwin is a qualitative researcher with the Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis at the University of Southern California. Corwin held Haynes and Spencer Foundation dissertation fellowships while working on a study examining college access and persistence for students from foster care. She is currently working on a series of hard copy and online game-based college access interventions. Randall F. Clemens is a Dean's Fellow in Urban Education Policy and research assistant at the Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis at the University of Southern California. His research focuses on educational reform, policy design, school and community partnerships, and qualitative research. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 3 Analyzing Fieldnotes: A Practical Guide Fieldnotes are a critical yet often underemphasized component of the research and writing process. In qualitative research, fieldnotes have long held a significant role in data collection and analysis. Seldom, however, are fieldnotes the focus of research methods sections or “how to” guides. Perhaps this is because researchers view fieldnotes as of minor importance compared to the overall research methodology or methods (Shank, 2006). Lederman (1990), highlighting the difficulty of categorizing fieldnotes, writes, “It is no wonder that fieldnotes are hard to think and write about: they are a bizarre genre. Simultaneously part of the “doing” of fieldwork and of the “writing” of ethnography, fieldnotes are shaped by two movements: a turning away from academic discourse to join conversations in unfamiliar settings, and a turning back again” (p. 72). Fieldnotes at the same time represent the research process and product. And yet, despite the use of fieldnotes as an essential part of qualitative research, few texts exist in which the authors fully explore the role and mechanics of fieldnotes, specifically within the field of education research. Notable exceptions include Emerson, Fretz & Shaw’s (1995) comprehensive overview Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes and Sanjek’s (1990) edited volume Fieldnotes: The Making of Anthropology. In this chapter, we present a synthesis of pertinent literature regarding fieldnotes and then offer a detailed description of how to analyze fieldnotes. The first section summarizes the philosophical and theoretical underpinnings of fieldnotes in qualitative research and is intended to highlight the interrelated nuances of collecting and analyzing fieldnotes. The second section shares concrete examples from a large scale qualitative ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 4 research project to illustrate the mechanics of analyzing fieldnotes during and after data collection. The ultimate goal of the chapter is to illustrate that analyzing fieldnotes is a process that begins from the moment one conceptualizes a study. Defining fieldnotes Much of qualitative research requires keen, detailed, and reflective observations of social settings. Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw (1995) describe ethnographic field research as involving two components: “First, the ethnographer enters into a social setting and gets to know the people involved in it…second, the ethnographer writes down in regular, systematic ways what she observes and learns while participating in the daily rounds of life of others” (p. 1). To record what they observe in the field, qualitative researchers rely on fieldnotes, or “detailed, nonjudgmental (as much as possible), concrete descriptions of what has been observed” (Marshall & Rossman, 2011, p. 139). Most often, fieldnotes chronicle settings, people, and activities (Merriam, 1988). High quality and carefully constructed fieldnotes provide “thick description” in which a researcher not only describes behavior but the context as well, thereby focusing on how people make meaning of their social worlds (Geertz, 1973). Fieldnotes can provide a portal from the reader to the research setting. For a discussion about the anthropological approach to ethnographic work, including collecting fieldnotes through extended fieldwork see chapter 3 of this volume (qv, Mills). Writing fieldnotes is a selective and active process. Accordingly, “the first stage of conventional, textual representation is the construction of fieldnotes” (Atkinson, p.89). As a researcher observes a social phenomenon or location, she determines what to ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 5 include in the fieldnotes; this process affects how she constructs and describes the social world. Stated in another way, fieldnotes are “authored representations of ongoing social life” (Emerson, 2001). Content and style of fieldnotes vary among researchers and projects. The content of fieldnotes are determined by a myriad of factors, including research questions, site selection, participants, and length and time of study. Fieldnotes might be collected for a project with solely one researcher or for a project involving a team of researchers from the same or different institutions. Some researchers include charts, diagrams, and pictures in their notes; others write minute details of social interactions or settings they have observed; and still others opt for using uniform observational protocols that can be shared among researchers. Some researchers choose to limit their fieldnotes to recording observations of setting and activities while others include more personal notations in the margins or in an additional column. Researchers may choose to integrate their own reactions and perceptions into the core of their fieldnote writing. “Jottings” taken down in the field serve to remind researchers of significant actions or possible connections to larger themes (see Emerson et al., 2001 and Saldana, 2009). In some instances, researchers indicate reflections through the notation “OC” (observer’s comments) that incorporate “researcher’s feelings, reactions, hunches, initial interpretations, and working hypothesis” (Merriam, 1988, p. 98). Some researchers maintain records solely through hand written notes while others rely on much more systematic and clearly typed up notes. For an interesting discussion of what to include in fieldnotes see DeVries (qv). ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 6 The nature of the data collection site, composition of research team, and topic of query influence when and how notes are recorded and written. While there is no prescribed format for fieldnotes, effective fieldnotes do involve an awareness of how data are being collected and recorded, including acknowledging the role of the researcher in that process. Take, for example, a study analyzing the social networks of drug dependent teenagers. Even after they have given consent to participate in the study, might a researcher and notepad significantly affect the types of behaviors and conversations in which the informants engage? How does the personal background of the researcher (e.g. age, race, gender) potentially affect data? Will research informants change their behavior because of the note taking process? Many aspects of data collection have significant implications for the ultimate trustworthiness of study findings. Analyzing fieldnotes begins with an awareness of how research design and methods can influence data collection and analysis. In the next section, we draw a connection between the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative research and their influence on fieldnotes. Understanding Fieldnotes Acknowledging the underlying paradigmatic assumptions that affect the way a researcher approaches each step of qualitative research is as important as understanding the mechanics of collecting fieldnotes. The purpose of acknowledging the foundational concepts in qualitative inquiry is not to devolve into an overly theoretical discussion removed from practical considerations. Instead, we attempt to highlight the importance of understanding one’s own perspective and positionality and the related implications for the research process. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 7 Every researcher either knowingly or unknowingly adopts the conventions of one or multiple paradigms. Put simply, a paradigm is a worldview.1 Paradigms range from positivist to constructivist, from believing an absolute, knowable reality exists to believing in a restricted, socially constructed reality. Each worldview contains its own set of ontological questions—how is reality defined, and what does existence mean—and epistemological questions—what is knowledge, and what is the relationship between the knower and the known. Other key questions relate to methodology and axiology. For instance, what phenomena does a researcher investigate and how, and what criteria does she use to judge their inquiry? Based on one’s own beliefs, the answers to these questions may vary drastically. The researcher’s own paradigmatic associations have important implications for the way she approaches research in general and fieldnotes in particular. For instance, an individual who situates himself or herself within a positivist epistemological framework believes in fieldnotes as a method to obtain truth (Kvale, 2007). A postmodernist, in contrast, believes fieldnotes to be constructions or, using Clifford Geertz’s (1973) language, “fictions,” because they are recreations of authentic acts. Similarly, a positivist may seek input from subjects about the content of fieldnotes in order to ensure the validity of data whereas a critical theorist may use fieldnotes as a venue to facilitate an evolving dialogue between researcher and participant. Using Fieldnotes to Improve Trustworthiness 1 For a more in-depth treatment of paradigms, see Kuhn (1970) and, for a description of qualitative paradigms, see Eisner (1990), Smith, (1990), and Guba and Lincoln (2005). ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 8 The caliber of fieldnotes has significant implications for data analysis and presentation. In the previous section, we discussed paradigms and the basic categories that define them, including ontological, epistemological, and methodological. Trustworthiness answers an axiological question by providing criteria to judge qualitative research.2 Considering the process and product of research, fieldnotes can improve the trustworthiness of data (Guba, 1981; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Sanjek, 1990) and limit misunderstanding from the text (Wolcott, 1990). Member checks and triangulation are two strategies that the researcher can use to improve the rigor of research. Ethnographic fieldnotes provide a helpful tool for member checks. By sharing fieldnotes and seeking input from informants about how data collected represents their experiences, fieldnotes can ensure more accurate data collection and analysis by the researcher (LeCompte & Goetz, 1982). Fieldnotes also allow for triangulation with alternative data sources, like interviews and document analysis, in order to reduce researcher bias and improve credibility (Guba, 1981). In relation to creating a useful archive of data—what Lincoln and Guba (1985) refer to as a research audit—fieldnotes fulfill a vital role, along with research diaries, memorandums, and interview transcripts. Lastly, descriptive fieldnotes minimize the chances that readers will misinterpret the text (Wolcott, 1990) and maximize the transferability—analogous to the quantitative concept of generalizability— of the research (Guba, 1981). Fieldnotes, whether quoted or summarized in the final 2 Trustworthiness (Guba, 1981; Lincoln & Guba, 1985) establishes criteria for rigorous research. The four criteria are credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. They are qualitative responses to criteria for quantitative research—internal validity, external validity, internal reliability, and external reliability. If the reader is interested in reading further about on-going discussions about criteria for qualitative research, we suggest beginning with Eisenhart and Howe (1992), and Lincoln (2001), and Tierney and Clemens (Qv). ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 9 product, allow for thick description (Geertz, 1973) in a text and permit the reader to vicariously experience the research setting. By presenting rich data, the researcher enables the reader to make an informed decision about whether or not the research may be applied to her own studies, a key concern of transferability. Questions to Consider Prior to Entering the Field (with Implications for Analysis) [to be included in a box / insert] How will I record my observations? What tools / supplies do I need (e.g. paper, pencil, tape recorder, camera)? How often will I take fieldnotes? Where and when will I write down fieldnotes? o Will the act of jotting down cause people in the social setting to act differently? When will I begin to code data, and how might that coding process affect subsequent observations? How does my own positionality affect what I might choose to write down? Analyzing Fieldnotes Data analysis entails a process of translation and negotiation when data collection and analysis often occur concurrently. Multiple techniques exist to analyze data, including content analysis, discourse analysis, grounded theory, and narrative analysis (Kvale, 2007). We acknowledge the value of each of these lenses to analyze data. For the purposes of clarity in this article, however, we adopt a grounded theory approach that emphasizes theory generation as a product of data collection (Charmaz, 2001; Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The mainstay of most qualitative analysis involves coding data. Like fieldnotes, coding purposes and strategies vary across methods, projects, and researchers. Nevertheless, the overarching goal of coding is to move from “unstructured and messy ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 10 data to ideas about what is going on in the data” (Richards & Morse, 2007, 133). Codes enable researchers to describe data, categorize data by topic, draw connections, and, consequently, develop theoretical concepts and identify themes (Richards & Morse, 2007).3 Once a researcher collects fieldnotes, she then codes data based on discrete categories (as illustrated below in the “Examining Fieldnotes” section). Gibbs (2007) offers a helpful list of items that may be coded:4 1. Specific acts, behaviors 2. Events 3. Activities 4. Strategies, practices or tactics 5. States 6. Meanings (including concepts, significance, symbols) 7. Participation 8. Relationships or interactions 9. Conditions or constraints 10. Consequences 11. Settings 12. Reflections on researcher’s role in the research process 3 See Richards & Morse (2007) for a discussion of the different types of codes, how to use them and how to manage codes. 4 See Gibbs (2007) for a more comprehensive description of coding that includes examples. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 11 Items coded are guided by the research question(s) and increasingly focused inquiry. While the researcher may start with a broad range of observable data, the categories should decrease as data collection proceeds. When a research project involves multiple researchers, coding involves a more lengthy process of identifying codes and discussing themes together. A group based analytic process creates an opportunity for colleagues to clarify, make connections and think through concepts with the support, critique and insight of other informed researchers. Due to the varying perspectives participating in the analysis of data, multiresearcher analysis has the potential to enhance the trustworthiness of findings in contrast to a lone researcher who runs the risk of missing key themes when working in isolation. For researchers analyzing data alone, robust literature reviews and member checking (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) can mitigate the potential to overlook key codes and themes. Examining Fieldnotes To illustrate one possible way to analyze data, we provide a step-by-step review of how a team of researchers analyzed fieldnotes for a large-scale qualitative project. In doing so, we aim to illustrate how analysis is not just a culminating step in the life-course of a study, but rather plays an integral role in the entire research process. It is imperative to note that while we present the steps below in a linear format, steps often occur in a simultaneous, recursive process and various phases of the research process inform each other. Background. In 2005, researchers from the Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis at the University of Southern California conducted a qualitative study funded by ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 12 the U. S. Department of Education to determine the key characteristics of effective college preparation programs. Six researchers, split among sites in California, collected data at twelve high schools during the course of three school years. Researchers used a case study approach (Stake, 1995) to examine differences and similarities in program implementation and effectiveness. Data collection entailed observations of a wide variety of school events and extracurricular activities as well as interviews and focus groups with students, teachers, administrators, and family members. Data collection was extensive, spanning multiple sites, informants, and researchers. Researchers relied heavily on fieldnotes to record observations, share data, and discuss emerging findings with the research team. Findings were summarized for academic, practitioner, and policymaker audiences. Using an inductive approach to hypothesis generation, grounded theory guided the overall approach to the study (Charmaz, 2001; Charmaz, 2007; Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Steps guiding data collection and analysis. In what follows, we outline the key components of the research process for the college access study and highlight how each phase influenced the analysis of fieldnotes. Step one: Research questions. The first step related to analysis involved reviewing literature related to the topic in order to inform the study’s research questions. Our goal was to identify major topics highlighted in discussions of college access in order to provide a focus for our observations. Major topics of interest included academic preparation, guidance, peers, family, mentors, culture, extracurricular activities, the timing of interventions, and the cost effectiveness of programs. There were two initial ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 13 overarching research questions: First, what role do students’ social support networks play in college preparation? And second, what elements in a college preparation program facilitate college preparedness? Step two: Site selection. Before we started collecting data, we had to identify sites that would provide rich sources of data. This step entailed researching and analyzing the demographics at each site and developing relationships with administrators in order to secure access. These two steps were critical to ensuring that the case study sites would allow for the collection and analysis of robust data and therefore contribute to the trustworthiness of data. Step three: Initial data collection. For the initial phase of data collection, researchers took notes about the activities and social interactions that transpired during the site visits. Fieldnotes across researchers lacked uniformity when initially written in notebooks. In most cases, one researcher would not be able to read the notations of the others. After researchers typed up their notes, we were able to share what we had written. Due to the benign nature of the study, we opted to clarify our presence in the classroom, explaining to students in general terms why we spent time with them. Consequently, students were at ease when researchers took notes. Researchers dressed in attire that was appropriate for the school environment, i.e. clothes a teacher would wear as opposed to business attire, and usually positioned themselves in the back of the room, thereby minimizing the distraction of additional adults in the classroom. Perhaps most relevant to implications for the trustworthiness of the study, the longitudinal nature of the study meant that students became familiar and at ease with the researchers’ presence in the classroom. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 14 Step four: Generation of fieldnotes. A considerably time intensive facet of the research process, and one critical to data analysis, involved typing up fieldnotes. Typing up fieldnotes was initially essential so that researchers could read each other’s notes and so that notes could be entered into a qualitative data analysis program (described below). At this stage, researchers also started to tease out significant themes and reflected on their observations. Saldana (2009) describes a process of “preliminary jottings” when researchers begin the coding process as they write up fieldnotes. In preliminary jottings, researchers start to write potential codes in the margins of notes or transcripts or in separate analytic memos to return to later. These notes assist researchers to develop codes in later stages of analysis. Saldana (2009) cautions researchers to “be wary of relying on your memory for future writing. Get your thoughts, however fleeting, documented in some way” (p.17). For the college access project, researchers kept a list of preliminary codes that were later shared with the research team in group meetings. Preliminary codes informed the first phase of data analysis. Step five: Initial data analysis. After fieldnotes were typed up and shared, researchers embarked on the process of identifying and defining initial codes. We used a data-driven approach for the first phase of analysis during which we attempted to let the data illustrate what was happening as opposed to imposing an existing theory on the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This process is also known as open or emic coding (Bernard & Ryan, 2010; Gibbs, 2009; Gough & Scott, 2000). At this point in data analysis, researchers coded fieldnote data by hand. We developed a code list and identified nine ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 15 major themes that we wanted to highlight during subsequent data collection. Excerpt from fieldnotes with open codes Observations Students were given a problem set of SAT-type questions to work on. One student didn’t begin for a while because he didn’t have a pencil. The advisor suggested that students “shouldn’t need help” and that they should work by themselves. A prize was offered to the first person to turn in their answers. Advisor asked the whereabouts of specific students. The other students present knew where most students were. Throughout the meeting, 8 students filtered in late. Most stayed the whole (25 min.) session. A small group came and the end of the session, signed in and then left Data-driven codes -ACTIVITY Observer Comments -SUPPLIES -PARTICIPATION -Was the student unprepared? Or could he not afford the necessary supplies? ADVISOR/LEADERSHIP -What if students did need STYLE help? -INCENTIVES -PEERS -EXPECTATIONS -PARTICIPATION -Why was the incentive necessary? What type of message does this send to students? - The students appear to be a tight-knit group. -Useful to track attendance and punctuality over time Step six: Additional data collection. Due to the complex nature of data collection (multi-researcher, multi-site), we opted to use an observational protocol across observations for the secondary phase of data collection. Subsections of the protocol included: o Background / setting o People in attendance ANALYZING FIELDNOTES o Agenda / Points discussed / Activities observed o Evidence of themes o Insights / themes / policy implications o Questions to follow up 16 Under “evidence of themes,” researchers recorded notes on the major themes identified during the literature review and initial coding: academic preparation, extracurricular activities, guidance, peers, family, mentors, and culture. The observational protocol facilitated analysis of data because it focused the researchers’ observations on specific themes and simplified cross-site analysis because researchers collected robust data on similar themes. Step seven: Detailed coding. After subsequent stages of collecting data and writing up fieldnotes over the course of several months, we started to enter fieldnote write-ups into Atlas.ti, a qualitative software analysis tool. The tool allowed the research team to code large amounts of data in a systematic way. With an advanced literature review complete (see Tierney, Corwin, & Colyar, 2005) and considerable amount of data collected, the research team shifted our analysis approach to a primarily concept-driven approach, also known as etic coding (Gough & Scott, 2000). By organizing data according to concepts from the literature, we were able to narrow our analysis and make it applicable to the literature. Gibbs (2009) points out that data driven and concept driven coding are not mutually exclusive, “most researchers move backwards and forwards between both sources of inspiration during their analysis” (p.46). Excerpt from fieldnotes with concept-driven codes ANALYZING FIELDNOTES Observations When we arrived, the counseling coordinator announced that she was available to meet with students one-on-one to work on their college essays. One student followed up with her. When asked, one senior knew that the college application deadline was Friday. The advisor told students they need to turn everything in online. He told students that sometimes the computer system crashes on the deadline day, suggesting that students could turn in materials a day late. 17 Data-driven codes Observer Comments - COUNSELOR AS INSTITUTIONAL AGENT -COLLEGE SUPPORT -PARTICIPATION -INSTITUTIONAL DEADLINES -LOW COLLEGE KNOWLEDGE -Why did only one student follow up? Preparedness or lack of comfort? -TECHNOLOGY -MISINFORMATION -DETRIMENTAL ADVICE -ADULT AS GATEKEEPER -Follow up to see when students turned in applications Step eight: Identification of themes. After a close reading of the fieldnotes and transcripts and engaging in line by line coding, the research team turned to expanding connections and identifying themes. Atlas.ti proved helpful in these conversations because we were able to print out reports according to codes. We could, for example, print out all excerpts from the text that pertained to “peers.” Seeing all data related to a particular theme was helpful to analysis. While Atlas.ti (and software analysis tools MAXQDA, NVivo, and Hyperresearch) offers functions to map out connections between themes, the research team opted to explore and expand upon themes in verbal discussions. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 18 Step nine: Trustworthiness. In order to make sure that study findings were trustworthy, researchers shared excerpts from fieldnotes and emerging findings with research participants. Participants were asked if fieldnotes and findings reflected their experiences accurately. In addition, researchers triangulated data by conducting observations, interviews, and focus groups with various stakeholder groups, e.g. students, teachers, administrators, counselors, and family members. This was a critical step as themes that emerged through triangulated data and feedback from participants affected follow-up data collection and analysis. Step ten: Presentation of findings. Writing up findings entailed a different focus of analysis. We first had to determine the audience for study results and then the best way to communicate findings to that audience. While the themes identified as salient did not change across audiences, presentation of data varied depending on whether a publication was intended for academic, practitioner, or policymaker audiences. Federal reports summarized findings and incorporated charts and tables; academic articles included rich data with thick descriptions and quotes from study informants; and practitioner monographs presented data in concise ways that included illustrative quotes. To see how the research team incorporated data from fieldnotes and analysis in narrative form, see Urban High School Students and the Challenge of Access: Many Routes, Difficult Paths (Tierney & Colyar, 2009). Conclusion Presentation of data follows the culmination of hours of diligent and methodical data collection and analysis. As with the research process, no one correct way exists to ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 19 present data. The manner in which fieldnotes are presented, however, has significant implications for the analysis of data from the reader’s perspective. Consider how the reader interprets data when she reads direct excerpts from fieldnotes versus summaries of observations. While both examples are textual representations, readers react differently to data depending on its presentation. Bourgois and Schonberg’s (2009) recent photoethnography, Righteous Dopefiend, for instance, offers a compelling example of fieldnotes in a text. The reader learns by reading actual fieldnotes and examining photographs interspersed between the authors’ analysis about the lives of heroin addicts living on the streets of San Francisco. The book invokes lively classroom discussions when we have pushed students to consider how the text might be different without the inclusion of their rich, detailed fieldnotes? Presentation of data depends on multiple factors, including the intent of the author, data available, audience, and publication type. In concluding this text, we want to highlight the potential of fieldnotes to elevate the imaginative possibilities of data presentation. Focusing attention to the collection, analysis, and presentation of fieldnotes heightens the potential of researchers to fulfill key purposes of qualitative inquiry—to illuminate and provoke, to address social issues and provide alternative solutions. The creative, thoughtful, and purposeful treatment of fieldnotes increases the likelihood that the researcher will connect the reader to researched in meaningful ways. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 20 References Atkinson, P. (2001). Ethnography and the representation of reality. In R.M. Emerson (Ed.), Contemporary Field Research (2nd ed., pp. 89-101). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. Bernard, H.R., & Ryan, G.W. (2010). Analyzing qualitative research: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bourgois, P., & Schonberg, J. (2009). Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley: University of California Press. Charmaz, K. (2001). Grounded Theory. In R.M. Emerson (Ed.), Contemporary Field Research (2nd ed., pp. 335-352). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Eisenhart, M.A., & Howe, K.R. (1992). Validity in educational research. In M.D. LeCompte, W.L. Millroy & J. Preissle (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research in education. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Eisner, E.W. (1990). The meaning of alternative paradigms for practice. In E.G. Guba (Ed.), The Paradigm Dialog (pp. 88-104). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Emerson, R.M. (2001). Fieldwork practice: Issues in participant observation. In R.M. Emerson (Ed.), Contemporary Field Research (2nd ed., pp. 113-152). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press. Emerson, R.M., Fretz, R.I., & Shaw, L.L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 21 Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic. Gibbs, G.R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. Los Angeles: Sage. Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine. Gough, S., & Scott, W. (2000). Exploring the purposes of qualitative data coding in educational enquiry: Insights from recent research. Educational Studies, 26, 339354. Guba, E.G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educational Communication and Technology, 29(2), 75-91. Guba, E.G., & Lincoln, Y.S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 191-215). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. LeCompte, M.D., & Goetz, J.P. (1982). Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research. Review of Educational Research, 52(1), 31-60. Lederman, R. (1990). Pretexts for ethnography: On reading fieldnotes. In R. Sanjek (Ed.), Fieldnotes: The making of anthropology (pp. 71-91). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Lincoln, Y.S. (2001). Varieties of validity: Quality in qualitative research. In J. Smart & W.G. Tierney (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 25-72). New York: Agathon Press. Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 22 Marshall, C. & Rossman, G.B. (2011). Designing qualitative research. (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. Kvale, S. (2007). Doing interviews. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kuhn, T.S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Richards, L. & Morse, J. M. (2007). Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sanjek, R. (1990). On ethnographic validity. In R. Sanjek (Ed.), Fieldnotes: The makings of anthropology (pp. 385-418). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Shank, G.D. (2006). Observing. Qualitative research: A personal skills approach. (2nd ed.) (pp. 21-37). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Smith, J.K. (1990). Alternative research paradigms and the problem of criteria. In E. G. Guba (Ed.), The Paradigm Dialog (pp. 167-197). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Stake, R.E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Tierney, W.G., & Clemens, R.F. (in press). Qualitative research and public policy: The challenges of relevance and trustworthiness. In J. Smart (Ed.), Overview of higher education: Handbook of theory and research. New York: Agathon Press. Tierney, W.G. & Colyar, J.E. (2009). Urban high school students and the challenges of access: Many routes, difficult paths. New York: Peter Lang. ANALYZING FIELDNOTES 23 Tierney, W.G., Corwin, Z.B., & Colyar, J.E. (Eds.). (2005). Preparing for college: Nine elements of effective outreach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Wolcott, H.F. (1990). On seeking--and rejecting--validity in qualitative research. In E. Eisner & A. Peshkin (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry in education: The continuing debate (pp. 121-152). New York: Teachers College Press.