Preventable Diseases

advertisement

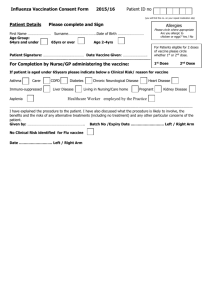

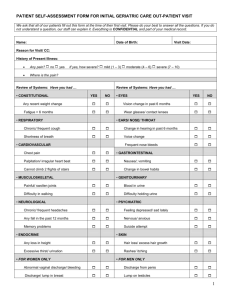

Vaccine Preventable Diseases-Why Worry and What Is New: The Best Available Evidence from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015 Mary Koslap-Petraco DNP, PNP-BC, CPNP, FAANP NAPNAP North Carolina chapter 22nd Annual Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Symposium William and Ida Friday Center Chapel Hill, NC October 9, 2015 Disclosures Dr. Mary Koslap-Petraco has nothing to declare Objectives Analyze the best available evidence for immunization practice for children and adolescents Explain the science behind the most current immunization recommendations for children and adolescents Change immunization practice in light of new evidence for children Identify signs and symptoms of vaccine preventable diseases that have recently recurred So What Is New New columns to stress availability of inactivated influenza vaccine and live-attenuated influenza vaccine starting at age 2 years Need for 2 doses of influenza vaccine for children 6 months to 8 years who receive influenza vaccine for the first time Children 9 years and older will need only 1 dose Children 6 months to 8 years who did not receive an H1N1 containing vaccine previously still need 2 doses of influenza vaccine this year No preference for LAIV over IIV for children So What is New For children 6 months to less than 12 months who are traveling outside the U.S. a single dose of MMR vaccine is required Noted on the ACIP schedule by a purple bar Clarifying changes were made to the wording in the footnotes for DTaP and pneumococcal vaccine Extensive revisions were made to the footnotes for meningococcal vaccine to clarify appropriate dosing schedules for high risk infants and children and for the use of different vaccines ACIP Recommendations This schedule includes recommendations in effect as of January 1, 2015 Any dose not administered at the recommended age should be administered at a subsequent visit, when indicated and feasible The use of a combination vaccine generally is preferred over separate injections of its equivalent component vaccines Vaccination providers should consult the relevant Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) statement for detailed recommendations, available online at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. Resources for Catch-up CDC has developed job aids for DTaP/Tdap/Td Hib PCV13 Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) Catch-Up Guidance for Children 4 Months through 18 Years of Age Haemophilus Influenzae type b-Containing Vaccines Catch-Up Guidance for Children 4 Months through 18 Years of Age Hib Vaccine Products: ActHIB, Pentacel, MenHibRix, or Unknown Hib Vaccine Products: Pedvax and Comvax Vaccines Only Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis-Containing Vaccines Catch-Up Guidance for Children 4 Months through 18 Years of Age http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html Pertussis Prolonged cough (3 months or longer) Post-tussive vomiting (pathognomonic in adults) Multiple medical visits and extensive medical evaluations Pertussis Among Adolescents Complications Hospitalization Medical costs Missed school and work Impact on public health system Tdap/Td for Persons Without Documentation of Pertussis Vaccination Preferred schedule: 0, 1, & 6 months Single dose of Tdap Td at least 4 weeks after the Tdap dose Second dose of Td at least 6 months after the prior Td dose For those who received 4 or 5 dose DTaP series Tdap is given at age 11-12 years Case Study An 8 year old child received 4 doses of DTaP before the 4th birthday. The child was given Td a week ago. Is this child appropriately immunized? What is your course of action? Tdap and Pregnancy Updated recommendation: Tdap should be given during EACH pregnancy Preferred during 27-36 week of pregnancy Vaccinate during third trimester or late in second trimester (after 20 weeks gestation) Vaccinating at this time maximizes transfer of antibodies to baby to protect baby before baby is able to begin DTaP series Use Tdap for routine tetanus and diphtheria booster or wound management if no prior Tdap dose Case Study An 17 year old adolescent just delivered a baby. She did not get Tdap during pregnancy. She received Tdap 2 years ago. Is the adolescent appropriately immunized? What is your course of action? DTaP Diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP). The fourth dose may be administered as early as age12 months, provided at least 6 months have elapsed since the third dose. Case Study A 9-year old child has received DTaP? What should you do? A 6 year old child receives Tdap. What should you do? HPV Vaccination Coverage Vaccination uptake has stalled Latest studies indicate that parents do not see need for HPV vaccine Parents also question safety of vaccine after severe side effects were reported by the press None of these reported side effects were found to be valid Nearly 50% of teen girls have begun HPV vaccine series Almost 1 in 3 does not complete vaccine series Only 1/3 of girls 13 through 17 years complete the 3-dose series Numbers of Cancers and Genital Warts Attributed to HPV Infections, U.S. CDC. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2013. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm HPV-Associated Cervical Cancer Incidence Rates by State, United States, 2006-2010 www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr Rates of HPV-Associated Cancer and Median Age at Diagnosis Among Females, United States, 2004–2008 *The vaginal cancer statistics for women between the ages of 20 and 39 is not shown because there were fewer than 16 cases. Watson et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2004-2008. MMWR 2012;61:258-261. ACIP Recommendation and AAP Guidelines for HPV Vaccine Routine HPV vaccination recommended for both males and females ages 11-12 years Vaccine can be given starting at age 9 years of age for both males and females; vaccine can be given ages 2226 years for males February 2015 ACIP recommended use of 9 valent HPV vaccine No HPV boosters necessary beyond 3 dose series (February, 2015) CDC. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of ACIP. MMWR 2007;56(RR02):1-24. HPV Vaccination Schedule ACIP Recommended schedule is 0, 1-2*, 6 months Following the recommended schedule is preferred Minimum intervals 4 weeks between doses 1 and 2 12 weeks between doses 2 and 3 24 weeks between doses 1 and 3 Administer IM CDC. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of ACIP. MMWR 2007;56(RR02):1-24. HPV Vaccine is an Anti-Cancer Vaccine Reduction in prevalence of vaccine-type HPV by 56% in girls age 14-19 with vaccination rate of just ~30% Our low vaccination rates will lead to 50,000 girls developing cervical cancer – that would be prevented if we reach 80% vaccination rates For every year we delay increasing vaccination rates to this level, another 4,400 women will develop cervical cancer Markowitz et al. JID 2013;208:385-393. CDC unpublished model – H. Chesson et al - for girls in US <13 at present, diff. betw 30% vs. 80% 3-dose coverage, lifetime cerv. ca. risk HPV Vaccine Is Safe, Effective, and Provides Lasting Protection HPV Vaccine is SAFE Safety studies findings for HPV vaccine similar to safety reviews of MCV4 and Tdap vaccines HPV Vaccine WORKS High grade cervical lesions decline in Australia (80% of school aged girls vaccinated) Prevalence of vaccine types declines by more than half in United States (33% of teens fully vaccinated) HPV Vaccine LASTS Studies suggest that vaccine protection is long-lasting; no evidence of waning immunity Garland et al, Prev Med 2011; Ali et al, BMJ 2013; Markowitz JID 2013; Nsouli-Maktabi MSMR 2013 Inadvertent Administration of HPV Vaccine during Pregnancy No safety concerns* raised by HPV4 in pregnancy registry CDC/FDA continue to monitor the safety of HPV vaccine, including reports in pregnant women through VAERS A retrospective analysis of pregnancy-associated HPV4 VAERS reports is in progress (2005-2012) >85% of reports were submitted from the Merck Pregnancy Registry so anticipate a similar safety profile For VSD, descriptive data of adverse events following inadvertent exposure to HPV4 during pregnancy by 2015 *death, life-threatening illness, hospitalization, prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability, congenital malformations HPV Vaccine Duration of Immunity Studies suggest that vaccine protection is longlasting; no evidence of waning immunity Available evidence indicates protection for at least 8-10 years Multiple cohort studies are in progress to monitor the duration of immunity Romanowski B. Long term protection against cervical infection with the human papillomavirus: review of currently available vaccines. Hum Vaccin. 2011 Feb;7(2):161-9. HPV Vaccine Impact: HPV Prevalence Studies NHANES Study National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data used to compare HPV prevalence before the start of the HPV vaccination program with prevalence from the first four years after vaccine introduction In 14-19 year olds, vaccine-type HPV prevalence decreased 56 percent, from 11.5 percent in 2003-2006 to 5.1 percent in 20072010 Other age groups did not show a statistically significant difference over time The research showed that vaccine effectiveness for prevention of infection was an estimated 82 percent Cummings T, Zimet GD, Brown D, et al. Reduction of HPV infections through vaccination among at-risk urban adolescents. Vaccine. 2012; 30:5496-5499. HPV Vaccine Impact: HPV Prevalence Studies, continued Clinic-Based Studies Significant decrease from 24.0% to 5.3% in HPV vaccine type prevalence in at-risk sexually active females 14-17 years of age attending 3 urban primary care clinics from 1999-2005, compared to a similar group of women who attended the same 3 clinics in 2010 Significant declines in vaccine type HPV prevalence in both vaccinated and unvaccinated women aged 13-26 years who attended primary care clinics from 2009-2010 compared to those from the pre-vaccine period (20062007) Kahn JA, Brown DR, Ding L, et al. Vaccine-Type Human Papillomavirus and Evidence of Herd Protection After Vaccine Introduction. Pediatrics. 2012; 130:249-56. Impact of Bivalent HPV Vaccine on Oral HPV Infection Of 7,466 women 18-25 years of age randomized to receive HPV vaccine or hepatitis A vaccine, 5,840 provided oral specimens at the final 4-year study visit Oral prevalence of identifiable mucosal HPV was relatively low (1.7%) There were 15 HPV 16/18 infections in the hepatitis A comparison group and 1 in the HPV vaccine group, for an estimated vaccine efficacy of 93.3% These results suggest that the vaccine provides strong protection against oral HPV 16/18 infection and may prevent HPV 16/18-associated oropharyngeal cancers Herrero R, et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLOS ONE 2013;8:e68329 31 Strong Start? Adolescent Immunization Coverage, US 13-17 year olds National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) 2006 vs. 2007 50 40 32.4 30.4 30 25.1 20 11.7 10 10.8 0 MCV4 Tdap HPV (females only) CDC. National and State Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2012 MMWR 2013; 62(34);685-693. 2006 2007 Impact of Eliminating Missed Opportunities by Age 13 Years in Girls Born in 2000 Percent Vaccinated 100 80 60 91 40 20 47 0 HPV-1 (girls) Vaccine Missed opportunity: Healthcare encounter when some, but not all ACIP-recommended vaccines are given. HPV-1: Receipt of at least one dose of HPV. MMWR. 63(29);620-624. Actual Achievable Evidence-based strategies to improve vaccination coverage Reminder/recall system Provider level (e.g., EMR prompts) Parent/patient level (e.g., postcards, telephone calls, text messaging) Standing orders Provider assessment and feedback Assessment of vaccination coverage levels within the practice and discussion of strategies to improve vaccine delivery Utilizing immunization information systems www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/universally/index.html Impact of Reminder/Recall on Vaccination Rates among Adolescents 60 50 49.5* 40.8 *p<0.05 44.3* Percent 40 29.5 30 Intervention 26.5* Control 20 15.3 10 0 Tdap MCV4 Vaccine Suh C et al. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1437-45 HPV-1 Evidence-Based Messages PARENTS SHOULD: Realize HPV vaccine is CANCER PREVENTION Understand HPV vaccine is best at 11- 12 years old Immune response is more robust when given at 11-12 years old Recognize importance of getting all 3 shots HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS SHOULD: Be familiar with all of the indications for HPV vaccine Make strong recommendations for receiving vaccine at 11 or 12 Be aware of, and interested in, systems that can improve practice vaccination rates HPV Vaccine Communications During the Healthcare Encounter HPV vaccine is often presented as ‘optional’ whereas other adolescent vaccines are recommended Some expressed mixed or negative opinions about the ‘new vaccine’ and concerns over safety/efficacy When parents expressed reluctance, providers were hesitant to engage in discussion Some providers shared parents’ views that teen was not at risk for HPV and could delay vaccination until older Goff S et al. Vaccine 2011;10:7343-9 Hughes C et al. BMC Pediatrics 2011;11:74 Goff S et al. Vaccine 2011;10:7343-9 Hughes C et al. BMC Pediatrics 2011;11:74 What’s in a recommendation? Studies consistently show that a strong recommendation from you is the single best predictor of vaccination In focus groups and surveys with moms, having a doctor recommend or not recommend the vaccine was an important factor in parents’ decision to vaccinate their child with the HPV vaccine Not receiving a recommendation for HPV vaccine was listed a barrier by mothers Unpublished CDC data, 2013. Just another adolescent vaccine Successful recommendations group all of the adolescent vaccines Recommend the HPV vaccine series the same way you recommend the other adolescent vaccines Moms in focus groups who had not received a provider’s recommendation stated that they questioned why they had not been told or if the vaccine was truly necessary Many parents responded that they trusted their child’s provider and would get the vaccine for their child as long as they received a recommendation from the provider Unpublished CDC data, 2013. Review 1. Give a STRONG recommendation Ask yourself, how often do you get a chance to prevent cancer? 2. Start conversation early and focus on cancer prevention Vaccination given well before sexual experimentation begins Better antibody response in preteens 3. Offer a personal story Own children/Grandchildren/Close friends’ children HPV-related cancer case 4. Welcome questions from parents, especially about safety Remind parents that the HPV vaccine is safe and not associated with increased sexual activity Tools for your Practice Tips for Talking to Parents about HPV Vaccine cdc.gov/vaccines/hpv-tipsheet Case Study A 14 year old male had his first HPV vaccine 2 months ago and had a second dose today. What is the next step for this adolescent in this series? Measles Measles in the United States 2014 644 cases from 27 states 23 measles outbreaks in 2014, including one large outbreak of 383 cases, occurring primarily among unvaccinated Amish in OH January 1 to January 15, 2015 • 102 cases reported Majority not vaccinated Reported in 14 states: CA, CO, IL, MN, MI, NB, NY, OR, PA, SD, TX, UT, and WA Current outbreak related to suspected US traveler who was unimmunized and traveled to endemic area Infected individual visited Disneyland….and the rest is history!!!!! Measles U.S. 2014* 216 cases reported from 15 states including 15 outbreaks 45 importations 22 from the Philippines 38 (85%) US residents 96% cases import-associated 38 cases (17%) hospitalized Cases in US residents (N=207) 63% unvaccinated 25% unknown vaccination status (90% of those adults) 12% vaccinated (including 8% with 2 or more doses) Among unvaccinated 83% were personal belief exemptors 6% unvaccinated travelers age 6-15 mos 7% too young to be vaccinated * Provisional reports to CDC through May 16, 2014 Global Burden of Measles Prior to Vaccine: 5-8 million deaths/year 77% decrease in incidence from 2000 to 2012 78% decrease in deaths from 2000 to 2012 (90% since 1985) 122,000 deaths in 2012 (~14 deaths/hour) Remains a leading cause of Vaccine Preventable Deaths in young children Most deaths in children under 5 years old What is Measles Febrile rash illness Most contagious of the vaccine preventable diseases Highly effective vaccine part of the routine immunization schedule Clinical Presentation Rash ~14 days after exposure (range 7-21 days) Fever (up to 105oF) Cough, Coryza, and/or Conjunctivitis Follows prodrome lasting 2-4 days Prodrome may include Koplick Spots Erythematous maculopapular eruptions Spreads from head to trunk to extremities Initially blanching Fades in order of appearance Measles Complications Condition Diarrhea Otitis media Pneumonia Encephalitis Death Percent reported 8 7-9 1-6 0.05-0.1 0.1-0.2 (2-15 in developing countries) Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE) 0.001 Measles and Immune Suppression Those infected with measles are vulnerable to other infections for up to 3 years Before vaccine was introduced virus was responsible for about 50 of deaths Including those caused by other childhood diseases Measles binds to cells that are meant to ‘remember’ past infections Virus actually resets the immune system Effectively wipes out previous immunity causing ‘immune amnesia’ Explains why measles vaccination programs are associated with reduction in childhood deaths from other disease Mina, M. J., Metcalf, C. J. E., de Swart, R. L., Osterhaus, A. D. M. E., & Grenfell, B. T. (2015). Longterm measles-induced immunomodulation increases overall childhood infectious disease mortality. Science, 348(6235), 694-699. Measles-Mumps-Rubella Recommendations Children – 2 doses at ages 12-15 months and 4-6 years For catch-up doses must be separated by 28 days CDC recommends that MMR be given at the earliest opportunity Travel Recommendations for Measles Persons aged ≥12 months should receive 2 doses Includes providing a 2nd dose to children prior to age 4-6 years Children aged 6-11 months should receive 1 dose Purple bar added to 2015 ACIP schedule If vaccinated at age 6-11 months, still need 2 subsequent doses at age ≥12 months Keys to Elimination in the U.S. High 2-dose MMR vaccine coverage High quality surveillance Rapid identification of and response to measles cases Reportable within 24 hours per Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) guidelines local health department and CDC Aggressive outbreak control measures Information sharing tools (Epi-X, HAN) Varicella Vaccine Minimum age: 12 months The second dose may be administered before age 4 years, provided at least 3 months have elapsed since the first dose For children aged 12 months through 12 years the recommended minimum interval between doses is 3 months If the second dose was administered at least 4 weeks after the first dose, it can be accepted as valid For persons aged 13 years and older, the minimum interval between doses is 4 weeks Case Study A 5 year old needs MMR and VAR. MMRV (Proquad) is available. What vaccine/vaccines will you choose? Are there any increased risks for administering Proquad? PPSV23 Indications for High Risk Children PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after last dose of PCV13 for children aged 2 years or older with the following conditions: Immunocompetent children with chronic heart disease (particularly cyanotic, congenital heard disease and cardiac failure, chronic lung disease (including asthma if treated with high-dose oral corticosteroids), diabetes mellitus, CSF leaks, cochlear implant Immunocompromising conditions: HIV infection, chronic renal failure & nephrotic syndrome, diseases associated with treatment with immunosuppressive drugs or radiation therapy including malignant neoplasms, leukemias, lymphomas and Hodgkins disease, or solid organ transplantation and congenital immunodeficiency Pneumococcal Vaccine for High Risk Children 6-18 years 1. If neither PCV13 nor PPSV23 has been received previously, administer 1 dose of PCV13 now and 1 dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks later 2. If PCV13 has been received previously but PPSV23 has not, administer 1 dose of PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after the most recent dose of PCV13 3. If PPSV23 has been received but PCV13 has not, administer 1 dose of PCV13 at least 8 weeks after the most recent dose of PPSV23 PPSV23 Indications for High Risk Children Children with atomic or functional asplenia including sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies congenital or acquired asplenic or splenic dysfunction A single dose of PPSV23 should be administered 5 years after the first dose to these children Pneumococcal Vaccine (PCV13) Indications for Children Pneumococcal vaccine 13 valent. (Minimum age: 6 weeks for pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV13] PCV13 is recommended for all children aged younger than 5 years Administer 1 dose of PCV13 to all healthy children aged 24 through 59 months who are not completely vaccinated for their age. Case Study Your patient is a 16 year old who is going for a cochlear implant. The adolescent has never received pneumococcal vaccine. What is your course of action? Influenza Vaccine 2015-16 Composition of 2015-16 Influenza vaccine will contain hemagglutinin (HA) derived from an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like virus, an A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like (Yamagata lineage) virus Represents changes in the influenza A (H3N2) virus and the influenza B virus as compared with the 2014– 15 season http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6430a3.htm 2014-16 Influenza Vaccine Quadrivalent influenza vaccines will contain these vaccine viruses, and a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like (Victoria lineage) virus, which is the same Victoria lineage virus recommended for quadrivalent formulations in 2013–14 and 2014–15 Emphasis on giving oseltamivir and zanamivir especially for high risk individuals Oseltamivir only antiviral approved for children Timing of Influenza Vaccination In more than 80% of influenza seasons, peak activity has not occurred until January or later In more than 60% of seasons, the peak was in February or later Immunization providers should begin offering vaccine as soon as it becomes available each season Providers should offer vaccine during routine healthcare visits or during hospitalizations whenever vaccine is available Timing of Influenza Vaccination Continue to offer influenza vaccine throughout the influenza season, especially to healthcare personnel and those at high risk of complications Continue to vaccinate even after influenza activity has been documented in the community Inactivated Influenza Vaccines and Egg Sensitivity Allergy to eggs must be distinguished from allergy to influenza vaccine Severe egg allergy is neither a precaution nor a contraindication for influenza vaccine Influenza Vaccine Administration for Children ACIP recommends that children aged 6 months through 8 years who have previously received ≥2 total doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2015, require only 1 dose for 2015–16 The two previous doses need not have been given during the same season or consecutive seasons Children in this age group who have not previously received a total of ≥2 doses of trivalent or quadrivalent influenza vaccine before July 1, 2015 require 2 doses for 2015–16 The interval between the 2 doses should be at least 4 weeks http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6430a3.htm Influenza Vaccine and Egg Sensitivity All vaccines should be administered in settings where personnel and equipment are available for rapid recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis All vaccination providers should be familiar with office emergency plan Staff should be prepared with: CPR certification epinephrine, and equipment for maintaining an airway Inactivated Influenza Vaccine (IIV) Dosage Age Group Dosage 6 through 35 months 0.25 mL 3 years of age and older 0.5 mL Schedule Age Group Number of Doses 6 months through 8 years 1 or 2 doses 9 years of age and older 1 dose Meningitis Vaccine in ChildrenClarifications Hib-MenCY – (MenHibrix) Minimum age 6 weeks – combination meningitis and Hib vaccine Indicated for children younger than 19 months of age with anatomic or functional asplenia including sickle cell disease) Administer at 2,4,6, and 12-15 months Meningitis Vaccine for Children Children aged 2 through 18 months with persistent complement component deficiency Administer infant series of Hib-MenCY at 2,4,6 and 12-15 months OR Starting at 9 months MCV4-D (Menactra) 2 dose primary series with at least 8 weeks between doses Children 19-23 months with persistent complement component deficiency who have not received a complete series of Hib-MenCY or MCV4-D Administer 2 dose primary series of MCV4-D at least 8 weeks apart Meningitis Vaccine in Children Children 24 months and older with persistent complement component deficiency or anatomic or functional asplenia (including sickle cell disease) who have not received a complete series of HibMenCY or MCV4-D (Menactra) Administer 2 dose primary series of MCV4-D or MCV4-CRM (Menveo) If MCV4-D is administered to child with asplenia (including sickle cell disease) do not administer MCV4-D until 2 years old and at least 4 weeks after completion of all PCV13 doses Meningitis Vaccine in Children Children aged 9 months and older who travel to countries in the African meningitis belt or to the Haij, administer age appropriate formulation and series of MCV4 for protection against serogroups A and W-13 Prior receipt of Hib-MenCY is not sufficient for children traveling to the meningitis belt or Haij Children aged 9 months-6 years at increased risk are recommended to be revaccinated 3 years after their primary series, and then at 5 year intervals if they remain at risk MCV4 for children 7 to 18 years and Older Administer MCV4 at age 11 through 12 years with a booster dose at age 16 years Administer 1 dose at age 13 through 18 years if not previously vaccinated Persons who received their first dose at age 13 through 15 years should receive a booster dose at age 16 through 18 years. Administer 1 dose to previously unvaccinated college freshmen living in a dormitory Persons with HIV infection who are vaccinated with MCV4 should receive 2 doses at least 8 weeks apart Meningitis B history B, C, and Y strains are the cause of meningitis in the US MCV4 covers A, C, Y, W135 strain B strain is not contained in MCV4 because when added to vaccine inactivates vaccine for other strains B strain is the cause of outbreaks in colleges NJ (Princeton) PA (Drexel University associated case with Princeton) CA (University of California Santa Barbara) RI (Providence University) most recent outbreak Meningitis B history More than 13,000 doses of a serogroup B vaccine were administered at Princeton University through an FDA investigational new drug application More than 17,000 UCSB students received a serogroup B vaccine through an FDA investigational new drug application CDC collaborated with local health departments to contain and control outbreaks Meningitis B Vaccine On October 29, 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed the first serogroup B meningococcal vaccine (Trumenba®) Approved for 10-25 years of age as a 3-dose series 0, 2, and 6 months On January 23, 2015, FDA licensed a second serogroup B meningococcal vaccine (Bexsero®) Approved for 10-25 years of age as a 2-dose series 0 and at least 1 month Meningitis B Vaccine ACIP voted unanimously on 2/26/15 meeting Limited recommendation for vaccine passed for controlling outbreaks of serogroup B meningococcal disease and for those at high risk Those with low immunity College students threatened with outbreak On 6/12/15 ACIP voted to approve a permissive recommendation for Meningitis b vaccine Providers can use these vaccines for people 10-25 years of age consistent with the labeled indication Use of Serogroup B Meningococcal (MenB) Vaccines in Persons Aged ≥10 Years at Increased Risk for Serogroup B Meningococcal Disease: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015 Vaccine Messaging Effective provaccine messages to curb the dangerous trend of vaccine refusal is needed Prior research on vaccine attitude change suggests that it is difficult to persuade vaccination skeptics and that direct attempts to do so can even backfire People’s antivaccination attitudes were successfully countered by making them appreciate the consequences of failing to vaccinate their children (using information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) This intervention outperformed another that aimed to undermine widespread vaccination myths. Horne, Z., Powell, D., Hummel, J., & Holyoak, K. (2015). Countering antivaccination attitudes. Crossmark, Early Edition > Zachary Horne, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504019112 VAERS Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System – passive system VAERS is a post-marketing safety surveillance program, collecting information about adverse events (possible side effects) that occur after the administration of vaccines licensed for use in the United States VAERS provides a nationwide mechanism by which adverse events following immunization may be reported, analyzed, and made available to the public VAERS also provides a vehicle for disseminating vaccine safetyrelated information to parents and guardians, health care providers, vaccine manufacturers, state vaccine programs, and other constituencies What are your responsibilities? Report any clinically significant adverse event noted following administration Storage and Handling-Vaccine Cold Chain Improper temperatures can make vaccines less effective A temperature-controlled environment used to maintain and distribute vaccines in optimal condition: 1. 2. 3. 4. Cold storage unit at the vaccine manufacturing plant Transport of vaccine to the distributor Delivery to the provider Ends with administration of the vaccine to the patient Vaccine Cold Chain Proper storage temperatures must be maintained at every link in the chain Provider Vaccine Cold Chain Management 1. Effectively trained personnel 2. Appropriate storage equipment 3. Efficient vaccine management procedures 4. Vaccine Storage and Handling Took Kit http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/storage/toolkit/defau lt.htm Screening Questions Immunization Action Coalition web site www.immunize.org Has wealth of information in easy to access format http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4060.pdf Evidence-Based Strategies Examples: standing orders reminder and recall AFIX: assessment, feedback, incentive, and eXchange References American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Mesles. In Pickering, L.K., Baker, C.J., Kimberlin, D.W., Long, S.S. (Eds.), Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 29th ed. (pp. 489-489). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (updated January 26, 2015). Retrieved from the web at http://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/outbreaks/vaccine-serogroupb.htm l Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007) Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of ACIP. MMWR. 56(RR02):1-24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Prevention and control of meningococcal diseaseRecommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 62(RR.#2):1-27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Vaccine storage and handling. Atkinson, W. L., Wolf, S. (Eds.). Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine preventable diseases-The Pink Book. 12th ed. (second printing). Atlanta, GA: The Public Health Foundation. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-storage.html References Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States 2014-15 influenza season. MMWR. August 15, 2014: 63(32);691-697. CDC. (2013 ). National and State Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13– 17 Years — United States, 2012. MMWR; 62(34):685-693. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). VAERS. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/providers/ reports.html Cummings T, Zimet GD, Brown D, et al. (2012 ). Reduction of HPV infections through vaccination among at-risk urban adolescents. Vaccine. 30:5496-5499. Federal Drug Administration. (2013). Flublok. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines /ApprovedProducts/ucm335836.htm Federal Drug Administration. (2012). Flucelvax. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines//approvedProducts /ucm328629.htm References Grohskopf, L., Olsen, S., Sokolow, L., Bresee, J., et. al. (2014). Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) — United States, 2014–15 Influenza Season: MMWR. 6391-7. Herrero R, et al. (2013). Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLOS ONE;8:e68329. Kahn JA, Brown DR, Ding L, et al. (2012). Vaccine-Type Human Papillomavirus and Evidence of Herd Protection After Vaccine Introduction. Pediatrics. (130)249-56. McNeil LK, Zagursky RJ, Lin SL, et al. Role of factor H binding protein in Neisseria meningitidis virulence and its potential as a vaccine candidate to broadly protect against meningococcal disease. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(2):234‐252 Romanowski B. (2011 ). Long term protection against cervical infection with the human papillomavirus: review of currently available vaccines. Human Vaccine. Feb;7(2):161-9. Strikas, R. (2015). Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP),* (2015). ACIP Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. (2015). Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedules for Persons Aged 0 Through 18 Years United States, MMWR; 64, 93-94. Watson et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2004-2008.(2012). MMWR. 61:258-26. Sources for Immunization Schedules, Changes, & Information Center for Disease Control www.cdc.gov/vaccines http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html Contains all schedules for child, adolescent, and adult immunization schedules American Academy of Pediatrics www.aap.org ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip The Red Book CDC vaccine storage and handling took kit http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/storage/toolkit/storage-handlingtoolkit.pdf