Carol O'Sullivan

advertisement

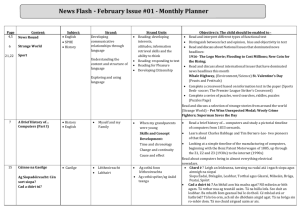

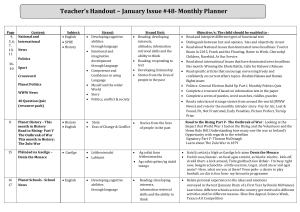

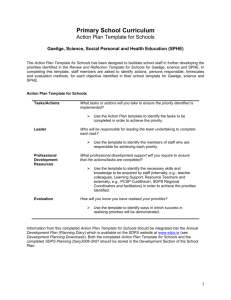

Research Showcase Mary Immaculate College, 3rd September 2013 SPHE (Primary) 1999 SPHE (Post-Primary) 2000 Rationale for SPHE Current Context Research Findings Recommendations 26% of 9-year olds have a raised BMI (Growing Up in Ireland, 2012) Increased incidence of mental health problems among young people (UNICEF, Ireland, 2011) 23% of 9-16 year olds have experienced bullying, either online or offline. (O’Neill and Dinh, 2013) Age of first sexual encounters has dropped (Mayock et al, 2007) High rates of alcohol consumption among adolescents (although this is decreasing) (ESPAD, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011). “SPHE is very important because it covers loads of subjects and it teaches you loads about life. We learn more about other people and what happens when we grow up. It allows us to be different. It helps us to have better relationships, better friends and to be yourself. It helps us to make decisions and realise the consequences. It helps us to take care of ourselves and to know what to do” (DES, 2009). “I would like to know more about emotional health especially before my exams” “I would like to learn more about stress and what happens” [SPHE could be used] “to focus on making important decisions, for example, if you thought a classmate was unhappy…and how you would deal with this sort of situation” (O’Higgins et al, 2007) “…an effective school health programme can be one of the most cost effective investments a nation can make to simultaneously improve education and health” (www.who.int/school_youth_health/en/) School health programmes are promoted as “a strategic means to prevent important health risks among youth and to engage the education sector in efforts to change the educational, social, economic and political conditions that affect risk” (ibid) Increased focus on Literacy and Numeracy Time allocation Not formalised at Senior Cycle Not an exam subject Sensitive nature of material Teacher confidence and capacity In most education systems there has been relative neglect of health education when compared with more traditional academic education (Fullan, 2001) Debate in Germany in relation to educational reform is notably lacking in references to health promotion (Paulus, 2005) In France, it has been found that schools set a low priority on health education (Do & Alluin, 2002, cited by Jourdan et al, 2011). School Health Policy and Practice Study (USA) demonstrated that while there were positive developments in relation to the recognition of health education at state and district level, this did not necessarily translate into implementation (Kann L, Brener ND, Wechsler H., 2007) Concrete action in schools difficult to initiate (Norway)(Samdal, 1999). Impact of local context: choices made by schools and students (Samdal, 1999; Tjomsland et al., 2009). Undertaken with pre-service primary school teachers (2012) Extension of similar project undertaken with pre-service post-primary teachers in 2010 and presented in 2012 (Mannix McNamara et al, 2012) Theory of Planned Behaviour Mixed-methods approach: survey and focus group Approved by MIC research ethics board Sample size 200, (convenience sample) Piloted with 20 students 165 responses to survey 74% (122) female; 26% (43) male Age Profile: 90% 18-19yrs 10% 20+ yrs Statement N Strongly Agree Unsure Disagree Strongly Disagree Agree (%) (%) (%) (%) (%) I am interested in SPHE 163 8 68 17 7 0 I enjoyed SPHE at 159 13 62 12 12 0.5 165 24 60 13 2 0 161 4 34 27 30 5 150 4 23 25 35 13 159 5 43 17 29 6 school I believe that SPHE is a relevant curricular area I learnt a lot from the SPHE class SPHE was taught very well in my primary school SPHE was taught very well in my post-primary school Statement N Strongly Agree Unsure Disagree agree There was a whole school approach Strongly Disagree 152 2 13 31 41 13 156 5 24 26 40 5 165 30 61 7 1 0.5 162 29 44 14 11 2 162 15 36 27 19 3 165 22 56 19 3 0 to teaching SPHE in my primary school There was a whole-school approach to teaching SPHE in my postprimary school I believe that SPHE is beneficial for students The fact that there is no exam in SPHE at post-primary level is an advantage to the subject SPHE should be mandatory in schools to Leaving Certificate level I look forward to teaching SPHE on leaving college SPHE Aspect Proportion ranked in top 3 (1,2 or 3) Proportion ranked in bottom 3 (8,9,or 10) Belonging and Integrating 38% 29% Relationships and Sexuality 31% 20% Substance Use 25% 38% Influences and Decisions 23% 37% Personal Safety 34% 26% Communications Skills 23% 34% Emotional Health 55% 15% Friendship 22% 30% Physical Health 37% 22% Self-management: A Sense of Purpose 14% 46% Five in sample All female Little recall of primary school experience Comments mainly based upon postprimary experience Content: Body Image Eating disorders Bullying Hygiene RSE Drugs education “a lot of it was common sense” “at the time we probably thought that you were too cool for it…you were able for something more” All agreed that SPHE was available in 1st/2nd and 3rd year of post-primary school 4 students stated that SPHE did not always take place when it was scheduled Group viewed SPHE as interesting Seen as “a break” Queried methodology: “you don’t want to be reading the text book…you’d rather join a conversation” “you don’t have to write…you can say it out…” Lack of structure: “you could be doing one thing one week and onto the next thing the following week” A number of concerns: Lack of experience of SPHE to date: impact on confidence and ability to teach Lack of knowledge Impact of social context Interests/responses of the children: “…it depends on if they respond or not” Positive attitudes: 84% see relevance of SPHE, 91% see SPHE as beneficial to students,78% looking forward to teaching SPHE Subjective norms: qualitative data demonstrates potentially negative subjective norms Perceived behavioural control: Teacher confidence, lack of knowledge, pupil responses emerged as barriers to perceived behavioural control. Three broad themes: Increasing Specific the recognition of the subject topics that should be addressed Resources and teaching methods More active approach to learning: “very interactive…with a group” “conversation more than reading from a text book or work sheet” Planned according to the needs of a particular class: “if they had a class at the start of the year to figure out what was relevant to that class…instead of sticking to a text book…in one class bullying might be an issue…and in another, relationships might be an issue”. More structure: “it needs more structure…it seemed to be just mixed in at random every week, you know” Divided opinion about making SPHE an exam subject: “it may be viewed more seriously if there was an exam at the end”/ “a lot of it is kind of opinions…so it’s going to be very hard to say that’s right or that’s wrong” Appointment of SPHE co-ordinator in every school Implemented whole school and community approach Located within the broader context of the Health Promoting School More designated time to SPHE More acknowledgement of teachers’ needs Mandatory SPHE qualifications at postprimary level “on teaching SPHE, one needs confidence, knowledge and also the where-with-all to understand the frailty of the situation. These are skills we need to obtain” (qualitative statement in student survey, September 2012) Thanks to Eva Devaney, Health Promotion Advisor, Mary Immaculate College, for her assistance with this research. Ajzen, I. (1991). “The Theory of Planned Behaviour”. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50, pp. 179-211. Department of Education and Skills (2009). Social, Personal and Health Education (SPHE) in the Primary School. www.education.ie ESRI/TCD/Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs (2009, 2010, 2011, 2012). Growing up in Ireland: National Longitudinal Study of Children. Dublin: Stationery Office. www.growingup.ie Fullan, M. (2001). The New Meaning of Educational Change. New York: Teachers’ College Press. Hibell, B. et al (2001, 2005, 2009, 2013) . The 1999, 2003, 2007, 2013 ESPAD Reports. Stockholm: Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs. www.espad.org Jourdan, D., Stirling, J., Mannix McNamara, P.& Pommier, J. (2011). “The influence of professional factors in determining primary school teachers’ commitment to health promotion”. Health Promotion International,Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 302-310. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mayock, P. , Kitching , K. and Morgan, M. (2007). RSE in the context of SPHE: An Assessment of the Challenges to Full Implementation of the Programme in Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: CPA/DES. Mannix McNamara, P. et al (2012). ‘Pre-service teachers’ experience of an attitudes to teaching SPHE in Ireland’ Health Education 112 (3). National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (1999). Primary School Curriculum: SPHE, Teacher Guidelines and Curriculum. www.ncca.ie National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2000). Post-Primary School Curriculum: SPHE, Teacher Guidelines and Curriculum. www.ncca.ie National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (2008). Primary Curriculum Review Phase 2. Dublin: NCCA. NicGabhainn, S, O’Higgins, S. and Barry, M. (2010). ‘The Implementation of social, personal and health education in Irish schools’. Health Education, 110 (6). O’Higgins, S. et al (2007). The Implementation of SPHE at Post-Primary School Level: A Case Study Approach. Dublin: SPHE Support Service (post-primary). O'Neill, B. & Dinh, T. (2013). “Cyberbullying among 9-16 year olds in Ireland”. Digital Childhoods Working Paper Series (No.5). Dublin: Dublin Institute of Technology Paulus, P. (2005). “From the Health Promoting School to the Good and Healthy School: New Developments in Germany” in Clift, S. and Bruun Jensen, B. (eds), The Health Promoting School: International Advances in Theory, Evaluation and Practice. Copenhagen: Danish University of Education Press. Samdal, O. (1999). “The Norwegian Network of Health Promoting Schools.”in Learnings from the Irish Network of Health Promoting Schools: Conference Report. Dublin: DoHC/DES. UNICEF Ireland (2011). Changing the Future – Experiencing Adolescence in Contemporary Ireland: Mental Health. www.unicef.ie Tjomsland, H., Larsen, T., Grieg Viig, N. & Wold, B. (2009). “ A Fourteen Year Follow-Up Study of Health Promoting Schools in Norway: Principals’ Perceptions of Conditions Influencing Sustainability”. The Open Education Journal, Vol.2, pp. 54-64.