Teaching Critical Thinking Skills: Increasing the

advertisement

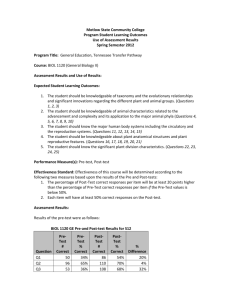

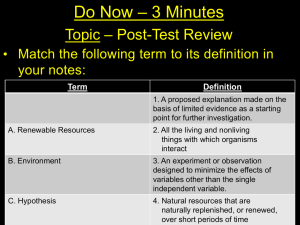

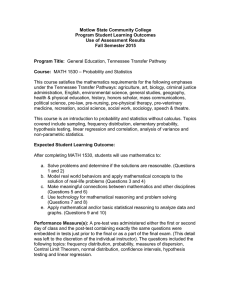

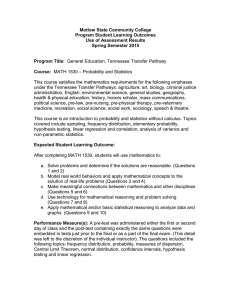

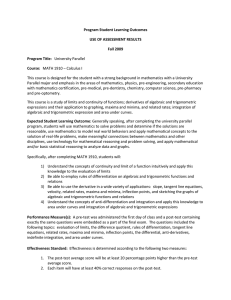

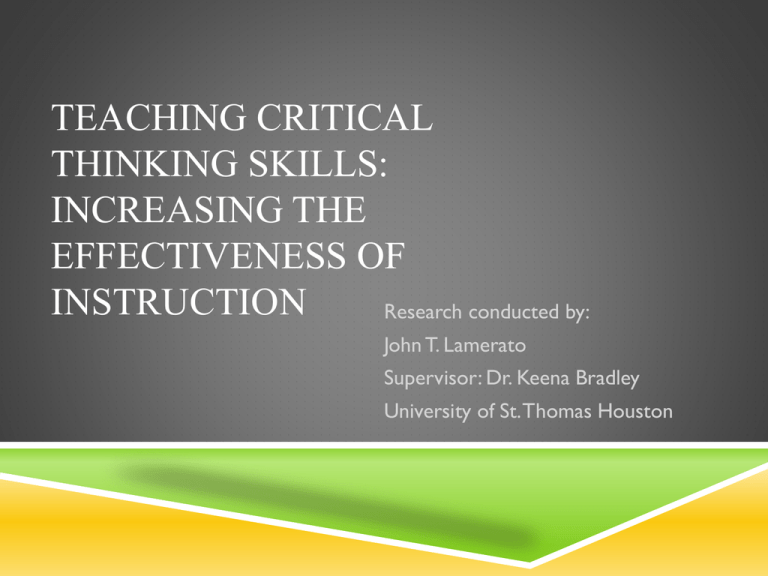

TEACHING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS: INCREASING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF INSTRUCTION Research conducted by: John T. Lamerato Supervisor: Dr. Keena Bradley University of St. Thomas Houston ABSTRACT American schools are struggling to keep up with International competition. Over the past decade, there have been a wide variety of efforts to help improve schools. These plans have focused on demanding that teachers be highly qualified, creating a core curriculum, and increasing accountability through standardized testing. So far, improvements have been slower than what was expected. Current research shows that what students truly need to be successful are critical thinking skills. Multiple methods of instruction of critical thinking skills exist. The goal of my research is to provide evidence delineating which method is the most productive. My subjects will be my current students, seniors at an urban high school near San Diego, CA. HYPOTHESIS Direct instruction produces the greatest measurable gains in critical thinking skills for male students who are seniors in high school DESIGN + MEASURE The study is quantitative action research, utilizing true experimental design research techniques. The instrument I used to measure the treatments of this action research was the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Test (practice edition). The test consisted of approximately 30 questions. Participants will be assessed on the number of questions that they score correctly. The scores from the pre-test will be compared against the numbers of the post-test to check for any trends. If there are clear cut results, the test results will lend evidence towards which mode of instruction is the most effective. METHOD Prior to any critical thinking instruction, senior students were randomly assigned to four separate groups of 20 by the registrar. On the first meeting of the classes, each group was given the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Test as a pre-test. The scores were used to establish a baseline for the analysis of the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. Over the next four weeks, three of the groups were provided with a different style of critical thinking instruction (direct instruction, random scenarios, modeling) twice a week for 15 minutes at a time. The fourth group served as the control and was not given any formal critical thinking instruction. At the end of four weeks, each group again took the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Test as the post-test. FINDINGS Variable Group Direct Treatment Control Pre-test M 35.75 36.45 SD 7.46 7.14 Post-test M 39.40 37.10 SD 6.37 6.86 Random Treatment Control 36.70 36.45 8.58 7.14 37.70 37.10 6.67 6.86 Modeling Treatment Control 37.60 36.45 7.30 7.14 38.85 37.10 6.57 6.86 Means and Standard Deviations for Treatment (n = 20) and Control (n = 20) Groups at Pre-test and Post-test Note: Direct = direct critical thinking instruction Random = critical thinking instruction using random scenarios Modeling = critical thinking using modeling FINDINGS The mean for students with direct instruction increased by 10.2% over the pre-test. The other treatments also saw increases of 2.7% for random scenarios and 3.3% for modeling. The control group also saw an increase of 1.7%, but the difference was less than all of the treatments. The almost 4 point increase in the mean of the direct instruction group on the post-test was more than double any of the other instructional methods. It should be noted that all of the means were at least marginally improved on the post-test. FINDINGS The standard deviations ranged from 6.37 – 6.86, all within the accepted deviation. The significant findings indicate that critical thinking instruction does have a positive impact on improving students’ critical thinking skills. The improvement observed is likely a real improvement that could be observed in the larger population. Specifically, direct instruction was shown to be the most effective style of critical thinking instruction. STRENGTHS My study was unique in that it focused on three specific styles of critical thinking instruction (direct, modeling, random scenarios) and included a control group. Using multiple styles opened up the possibility for finding out not only if critical thinking instruction produced positive results, but which specific style had the most impact. An additional strength of this study is the ease of potential replication. The assessment instrument, The Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Test is a nationally recognized exam and is easily accessible. All three forms of critical thinking instruction were outlined and all were taught four the same period of time (15 minutes). No additional training was required to teach the three critical thinking styles. WEAKNESSES The first limitation was fairly atypical when compared with similar studies. A notable limitation was the lack of female students involved in the study. Previous research also indicates that the limited number of time spent instructing students in the current study may also appear to be a limitation. This limitation was due to the time constraints of a high school setting and the limit of resources to conduct the research on a larger scale. RECOMMENDATIONS Teachers should primarily focus on direct instruction when teaching students critical thinking skills Students need to be trained to complete tasks that cannot be completed by computers and using direct instruction to teach critical thinking skills is an important first step. REFERENCES Balcean, Phillip L. (2011).The Pedagogy of Critical Thinking: Object Design Implications. U.S.-China Education Review, 8,354 – 363. Broom, Catherine (2011). From critical thinking to critical being. History Teacher 24, (2), 16 – 27. Case, Roland & Wright, Ian (2007).Taking seriously the teaching of critical thinking. Canadian Social Studies 32, 22 – 23. Choy, S. Chee (2012). Reflective thinking and teaching practices: A precursor for incorporating critical thinking into the classroom. International Journal of Instruction 5, (1), 167 – 182. Clifton, Gill (2012). Supporting the development of critical thinking: Lessons for widening participation.Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning 14, (2), 29 – 39. Crenshaw, Phillip (2011). Producing Intellectual Labor in the Classroom:The Utilization of a Critical Thinking Model to Help Students Take Command of Their Thinking. Journal of College Teaching and Learning, 8, (3), 14. REFERENCES Daniel, Mare-France & Lafortune, Louise (2005). Modeling the Development Process of Dialogical Thinking. Communication Education, 54, (4), 334-354. El Hassan, Karma & Madhum, Ghida (2007). Validating the Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal. Higher Education (54), 361-383. Elder, Linda & Paul, Richard (2010). Critical thinking: Competency standards essential for cultivation of intellectual skills. Journal of Developmental Education 34, (2), 38-39. Enabulele, Augustine (2011). Critical thinking in secondary language arts: Teacher perceptions and relevant strategies. Journal of Classroom Interaction 47, (2,) 7 -12. Gearon, Christopher J. (September 17, 2012). “High School Students Need to Think, Not Memorize.” US News. http://www.usnews.com/education/highschools/articles/2012/09/ 17/high-school students.html REFERENCES Kenny, Charles. (August 19, 2012). “ The Real Reason Why Schools Stink.” BusinessWeek. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-08-19/the-real-reason-americas-schoolsstink. html Marin, Lisa M. & Halpern, Diane F. (2011). Pedagogy for developing critical thinking in adolescents: Explicit instruction produces greatest gains. Thinking Skills and Creativity 6, (1), 7 – 21. Roberts, Terry. (2012). Teaching Critical Thinking: Using Seminars. Eye on Education, 76. Snyder, Lisa Gueldenzoph & Snyder, Mark J. (2008). Teaching critical thinking and problem solving skills. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal 50, (2), 90-99. Spring, Joel. (2010). American Education. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.