Writing Examples

advertisement

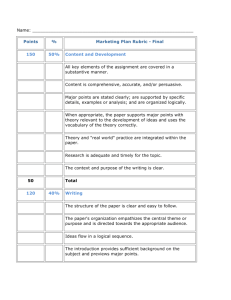

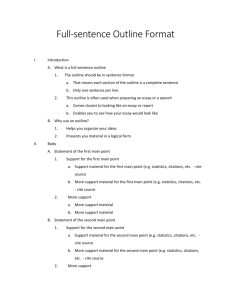

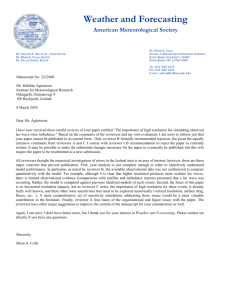

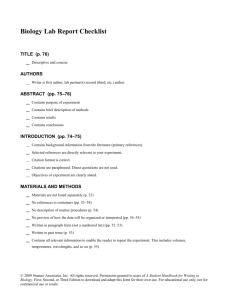

Hank Walker Ford Motor Company Design Professor II and Department Head Department of Computer Science and Engineering Research Papers Technical Reports Reports Vary tremendously in length/scope Long report about work of a committee Short report about a particular topic Technical Documentation Vary in purpose Design Development Users White Papers Memos Web Sites etc. The type of writing you do will vary depending on many factors Difficult to give universal structure But, there are some things common to most or all writing Probably the most important thing to consider. This will determine everything from structure to individual word choice. You think about this before you begin to write anything! You are writing for the audience, not for yourself. What will be the background of those reading this work? What prior knowledge will they have? What expectations will they have? What do I need to tell them so that they can understand the paper? What is the reason someone will read this document? What information is most important to convey to the reader? What will the “life” of this document be? Will the audience change? Will the document change? The way you structure a document can have more effect than the actual sentences it contains. Again, think about the goals of a person reading. How would they expect the document to be organized? What do they need to do with the document? Technical papers are not novels. With rare exceptions of short memos, people will not just sit down one day and read your document from beginning to end. First: Read Title Second: Read Abstract Third: a. Browse figures/captions b. Review citations Fourth: Read small portions to get main idea Only if someone is really interested do they sit down and read the whole paper from start to finish. 1. 2. Look at the Title Check either: A. B. 3. 4. Index Table of Contents Find section with the specific material needed Find relevant subsection within that section Then, read the material of relevance. Make it easy for someone to understand the structure of the document Follow conventions Clearly label/section document Find information they want within the document Use White Space Indentation Line breaks Page breaks Keep paragraphs short Use lists, bullet points Maintain clear section headings. There are three stages of presentation: 1. 2. 3. Importance: Attract Attention Create Interest Convey Information You don’t get to stage 2, unless you satisfy stage 1 You don’t get to stage 3, unless you satisfy stage 2 Although stage 3 is the most important, it’s pointless unless you meet the first two stages. Applies to posters/presentations, but also to papers The RESEARCH! You have to have some purpose for writing However, people will not learn about the research unless they actually read your paper This also has implications for how and where you publish your paper We will discuss some specifics for writing research papers. This is commonly done in graduate school. Material developed for graduate students But, many principles carry forward to other writing Title Abstract Introduction Previous Work Main Work (ideas/theory/exposition) Possibly combined into main work section Conclusion If needed Results Possibly in several sections Implementation Possibly including background information With future work Acknowledgements References Appendices Don’t underestimate title importance Memorable titles can help people remember the paper The title will be used for searching, later Remove unnecessary words Watch for misleading words Motivation and Summary By the end of the introduction, someone should be able to tell someone else what you did, and why. But probably not give any details about how Keep the introduction short, relative to the rest of the paper. Early on in the paper, you must make the case for why you are doing this This should not be too long If you have to spend too long to say why someone should read the paper, then there’s probably not a good reason The motivation is not why you are writing the paper, it’s just there to get people to read it Sometimes this is more important than other times – sometimes motivation is obvious You want to make it clear what the main results of your paper are. Don’t “hide” them or make them a “surprise” at the end Remember, most people will not read your full paper – you still want them to know the main results Should always be in the abstract Should be in the introduction of the paper Main Results, Contributions, Thesis Statement Can be in the conclusion Could be a subsection, a paragraph, a bulleted list, or a sentence Should be easy to find/locate Should make clear what is the new, unique contribution of this work It is not a summary of everything you’ve done, or even a summary of the paper Just list the key point(s) that are new to your work. A short statement that summarizes what the focus of the paper is Can help to focus your writing, presentation, and research The goal of the paper is to show why the thesis statement is important and true (or false…) Provide references to relevant material What are the key papers that someone should read to understand this? What are the most relevant related papers/alternatives? Demonstrate that you are familiar with the main research in the area Ensure you cite all the relevant work Especially the papers of those who will read yours… Can’t cite everything; cite the most important things Usually, citations to textbooks aren’t needed Unless that textbook provides a unique derivation, a particular summary, etc. If necessary provide background summary of prior work For example, if you are building on your own prior work Make sure that prior work is separated from new work You want to clearly delineate what is new vs. what is old. When giving citations to previous work, it is good to show how your work fits in with that prior work. This is the main, core part of your paper It should be the part that you are most confident in, and have the most to say about It is important that you are clear and accurate. You are not just presenting a list of what you did. Every piece of research has lots of “infrastructure” work that goes on behind it – you don’t need to go into this, unless it is critical You don’t need to discuss “dead end paths” that you pursued One exception is if it is very likely someone else would follow that dead end path You research is evaluated on results, not process. You want to develop your material clearly Usually, someone will read this section in order Don’t pull ideas/material from nowhere Make sure that information is presented in a logical order Think of it as telling a (technical) story: Keep the story moving Don’t refer to things that the reader has no knowledge of Make sure the reader understands what has happened! Avoid tangential topics Make the section about the main results, not the interesting “side” items Use appendices if necessary Make sure there is a clear overview Avoid going directly into details if the person doesn’t have the overall picture Often, overview sections or figures are helpful You want to demonstrate all of the core ideas that you discussed in practice Idea is to show that what you presented works, and give some sense of how well it works Pick good test cases, that cover a range of situations If you discussed something, show the results Ones that allow comparison Ones that allow evaluation of parts of your technique Ones that simulate “real world” cases You need to provide comparisons to other work, whenever possible This lets people evaluate your work Now that we have seen the work in the paper, what can we conclude? What has been the “contribution” of this work? What insights does this work offer? What does this now allow us to do? Conclusion should not be just a summary of what was in the paper – that is obvious. Usually part of the conclusion Not always included, but a good idea if possible People want to know that the paper is not a “dead end” What more could be done? If I like this area, what could I work on next? Is this likely to stimulate future work? Can be a “defense” against reviewers. Avoid using “throwaway” future work In computer science, you can always say you want to improve performance, port to a new system, or integrate with something else. Better to have one or two solid areas for future work than 10 that aren’t developed. Don’t just state areas, give some indication of the challenges/opportunities Why will that be worthwhile? What are some obstacles that will be faced in that extension? Make sure you are writing to the appropriate audience Usually, this is to other researchers in the field Not to novices – they will know the basics of the field Not necessarily to just the foremost experts in the area – they will not be familiar with every bit of prior work Not to experts in all areas – they may not be familiar with simpler concepts from other fields Some papers (e.g. literature reviews) are for more general, less expert, audiences Give them the background they need to understand the paper Particularly if you rely on another technique; don’t make them read other papers before they can read yours Not always possible – sometimes there is too much to do Notation might not be standardized Explain the notation as needed The concepts might already be known Do not oversell your work Do not promise more than you deliver Do not try to make your work have more impact than it reasonably does You probably have a higher opinion of your work than others do or ever will. Readers are annoyed if they spend their time reading your article, only to find it didn’t do what was promised. Do not undersell your work Don’t put in so many disclaimers that you discourage someone from reading/following it Point out problems, especially key ones, but: Your goal is not to point out every conceivable flaw If necessary, point out why problems might not be so bad You are writing the paper because you have something new to present, that others should find valuable. Those reading the paper will often have questions/objections. You want to answer/address these in the paper This is key to getting the paper accepted through review, but also for getting the paper accepted after publication Think: “If I were a reviewer, what would I have questions about?” Find a way to address those directly If they are technical concerns and you have not addressed them in the work, show that you’ve thought about them What examples should be included? What tests should be provided? People will usually look at figures before they read the text You want the figures to stand on their own as much as possible Be sure that your captions clearly describe what is in the figure. Do not rely on the text to describe the figure. Always a tricky proposition Your goal in the paper is to show how good your work is. You have spent a great deal of time on your own approach. You must be fair to prior work, but you probably can’t devote as much effort to replicating it. If standardized comparisons can be made, use them If you implement another method for comparison, be sure to do your best with it If not, be sure to clearly state what you did not do, and why. It is not OK to just present your material and assume it should be accepted That does not show any new contribution over the state of the art Exception: if it is truly the first time someone has accomplished something If you cannot provide comparisons, at least provide concise, clear arguments that evaluate your method vs. other methods. If possible, get someone else to read your work They should be willing to give direct, honest feedback Take their evaluations to heart When reviewers reply with objections, don’t blame the reviewer If the reviewer didn’t understand it, it’s probably your fault Make sure that you address their concerns Sometimes it is only a style/writing issue! Sometimes they have found more fundamental flaws Even these can sometimes be addressed by writing differently. There are (very rare) exceptions where reviewers are way off Always be polite and respectful in your responses, anyway