balance of payments

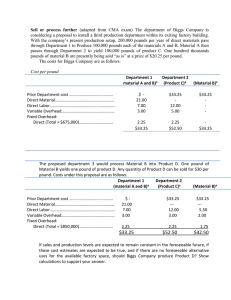

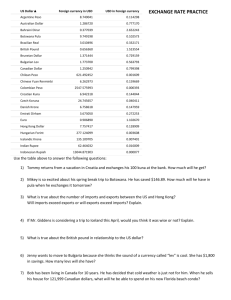

advertisement

Chapter 38: Balance of Payments, Exchange Rates, & Trade Deficits In chapter 37 we examined comparative advantage as the underlying economic basis of world trade and discussed the effects of barriers to free trade. Now we introduce the highly important monetary and financial aspects of international trade. International Financial Transactions This chapter focuses on international financial transactions, the vast majority of which fall into two broad categories: international trade and international asset transactions. International trade involves either purchasing or selling currently produced goods or services across an international border. Examples include an Egyptian firm exporting cotton to the U.S. and an American company hiring an Indian call center to answer its phones. International asset transactions involve the transfer of the property rights to either real or financial assets between the citizens of one country and the citizens of another country. It includes activities like buying foreign stocks or selling your house to a foreigner. In either case, money flows from the buyers of the goods, services, or assets to the sellers of the goods, services, or assets. When the people engaged in any transactions are both from places that use the same currency, what type of money to use is not an issue. However, when the people involved in an exchange are from places that use different currencies, intermediate asset transactions have to take place: the buyers must convert their own currencies into currencies that the sellers use and accept. The Balance of Payments A nation’s balance of payments is the sum of all the financial transactions that take place between its residents and the residents of foreign nations. Most of these transactions fall into the two main categories that we have just discussed. But the balance of payments also includes international transactions that fall outside of these main categories, things such as tourist expenditures, interest and dividends received or paid abroad, debt forgiveness, and remittances made by immigrants to their relatives back home. Table 38.1 is a simplified balance of payments statement for the United States in 2009. The balance of payments statement is organized into two broad categories; the current account and the capital and financial account. 1. Current Account- summarizes U.S. trade in currently produced goods and services. Items 1 and 2 show U.S. exports and imports of goods. Exports have a (+) sign because they are a credit; they generate flows of money to the United States. Imports have a (-) sign because they are a debit; they cause flows of money out of the U.S. Balance on Goods- A country’s balance of trade on goods is the difference between its exports and its imports of goods. If exports exceed imports, the result is a trade surplus. If imports exceed exports, there is a trade deficit on the balance of goods. We note in item 3 that in 2009 the U.S. incurred a trade deficit on goods of $517 billion. Balance on Services- the U.S. exports not only goods such as airplanes and computer software, but also services, such as insurance, consulting, travel, and investment advice to residents of foreign countries. Summed together, items 4 and 5 indicate that the balance on services, item 6, was $138 billion. The balance on goods and services shown in item 7 is the difference between U.S. exports of goods and services, and imports of goods and services. In 2009, U.S. imports of goods and services exceeded U.S. exports of goods and services by $379 billion. So a trade deficit of that amount occurred. In contrast, a trade surplus occurs when exports of goods and services exceed imports of goods and services. Global Perspective 38.1 shows U.S. trade deficits and surpluses with selected nations. Balance on Current Account- items 8 and 9 are listed as part of the current account because they are international financial flows. For instance, item 8, net investment income represents the difference between the interest and dividend payments foreigners paid U.S. citizens and companies for services provided by U.S. capital invested abroad, and the interest and dividends the U.S. citizens and companies paid for the services provided by foreign capital invested here. Observe that in 2009 U.S. net investment income was a positive $89 billion. Item 9 shows net transfers, both public and private, between the U.S. and the rest of the world. Included here is foreign aid, pensions paid to U.S. citizens living abroad, and remittances by immigrants to relatives abroad. These $130 billion of transfers are net U.S. outpayments, and therefore listed as a negative number. By adding all transactions in the current account, we obtain the balance on current account, shown in item 10. In 2009 the U.S. had a current account deficit of $420 billion. This means these transactions created out-payments from the United States greater than in-payments to the United States. 2. Capital and Financial Account- summarizes U.S. international asset transactions which consist of two separate accounts. Capital Account- mainly measures debt forgiveness. It is a net account or one that can be either + or -. The $3 billion listed in item 11 tells us that in 2009 Americans forgave $3 billion more of debt owed to them by foreigners than foreigners forgave debt owed to them by Americans. The (-) sign indicates a debit, or out-payment. Financial Account- summarizes international asset transactions having to do with purchases and sales of real or financial assets. Line 12 lists the amount of foreign purchases of assets in the U.S. It has a (+) sign because any purchase of an American owned asset by a foreigner generates a flow of money toward the American who sells the asset. Line 13 lists U.S. purchases of assets abroad. These have a (-) sign because such purchases generate a flow of money from the Americans who buy foreign assets toward the foreigners who sell them those assets. Items 12 and 13 combined yielded a $423 billion balance on the financial account for 2009, line 14. The balance on the capital and financial account, line 15, is $420 billion. It is the sum of the $3 billion deficit on the capital account and the $423 billion surplus on the financial account. Observe that this $420 billion surplus in the capital and financial account equals the $420 billion deficit in the current account. The two numbers always equal, or balance. Why the Balance? The balance on the current account and the capital and financial account must always sum to zero because any deficit or surplus in the current account automatically creates an offsetting entry in the capital and financial account. People can only trade one of two things with each other: currently produced goods and services or preexisting assets. Therefore, if trading partners have an imbalance in their trade of currently produced goods and services, the only way to make up for that imbalance is with a net transfer of assets from one party to another. Specifically, current account deficits simultaneously generate transfer of assets to foreigners, while current account surpluses automatically generate transfers of assets from foreigners. Flexible Exchange Rates There are two pure types of exchange rate systems. A flexible or floating exchange rate system- through which demand and supply determine exchange rates and in which no government intervention occurs. A fixed exchange rate system- through which governments determine exchange rates and make necessary adjustments in their economies to maintain those rates. We will be looking at flexible exchange rates. Let’s examine the rate, or price, at which U.S. dollars might be exchanged for British pounds. In figure 38.1 we show demand Dl of pounds and supply Sl of pounds in the currency market. The demand for pounds curve is down-sloping because all British goods and services will be cheaper to the U.S. if pounds become less expensive to the U.S. That is, at lower dollar prices for pounds, the U.S. can obtain more pounds and therefore more British goods and services per dollar. The supply of pounds curve is upsloping because the British will purchase more U.S. goods when the dollar price of pounds rises. The intersection of the supply curve and the demand curve will determine the dollar price of pounds. Here, that price, or exchange rate, is $2 = 1£. Depreciation & Appreciation An exchange rate determined by market forces can, and often does, change daily like stock and bond prices. These exchange rates can be found in a good daily newspaper or on the internet. When the dollar price of pounds rises, for example, from $2 =1£ to $3 = 1£, the dollar has depreciated relative to the pound, and the pound has appreciated relative to the dollar. When a currency depreciates, more units of it (dollars) are needed to buy a single unit of some other currency (pounds). When the dollar price of pounds falls, for example, from $2=1£ to $1=1£, the dollar has appreciated relative to the pound. When a currency appreciates, fewer units of it (dollars) are needed to buy a single unit of some other currency (pounds). In our U.S.-Britain example, depreciation of the dollar means an appreciation of the pound, and vice versa. When the dollar price of a pound jumps from $2 = 1£ to $3= 1£, the pound has appreciated relative to the dollar because it takes fewer pounds to buy $1. At $2=1£, it took £½ to buy $1; at $3=1£, it takes only £⅓ to buy $1. In general, the relevant terminology and relationships between the U.S. dollar and another currency are as follows. If the demand for pounds increases or the supply of pounds decreases, the pound will appreciate. This means that anything which raises the dollar price of a pound will cause it to get stronger. If the demand for pounds decreases or the supply of pounds increases, the pound will depreciate. This means that anything which lowers the dollar price of a pound will cause it to get weaker. Determinants of Exchange Rates What factors would cause a nation’s currency to appreciate or depreciate in the market for foreign exchange? These factors will shift the demand or supply curve for a certain currency. 1. Changes in Tastes- Any change in consumer tastes or preferences for the products of a foreign country may alter the demand for that nation’s currency and change its exchange rate. For example, if technological advances in U.S. wireless phones make them more attractive to British consumers and businesses, then the British will supply more pounds in the exchange market to purchase more U.S. wireless phones. The supply of pounds will shift right, causing the pound to depreciate and the dollar to appreciate. In contrast, the U.S. demand for pounds curve will shift to the right if British woolen apparel becomes more fashionable in the United States. So the pound will appreciate and the dollar will depreciate. 2. Relative Income Changes- A nation’s currency is likely to depreciate if its growth of national income is more rapid than that of other countries. As total income rises in the U.S., people there buy both more domestic goods and more foreign goods. If the U.S. economy is expanding rapidly and the British economy is stagnant, U.S. imports of British goods, and therefore U.S. demands for pounds will increase. The dollar price of pounds will rise, so the dollar will depreciate. 3. Relative Inflation Rate Changes- Other things equal, changes in the relative rates of inflation of two nations change their relative price levels and alter the exchange rate between their currencies. The currency of the nation with the higher inflation rate tends to depreciate. For example, if inflation is zero in Britain and 5% in the U.S., American consumers will seek out more of the now relatively lower-priced British goods, increasing the demand for pounds. British consumers will buy less of the now relatively higher-priced U.S. goods, reducing the supply of pounds. This combination of increased demand for pounds and reduced supply of pounds will cause the pound to appreciate and the dollar to depreciate. 4. Relative Interest Rates- Changes in relative interest rates between two countries may alter their exchange rate. Suppose that real interest rates rise in the U.S. but stay constant in Britain. British citizens will then find the U.S. a more attractive place in which to loan money directly or loan money indirectly by buying bonds. To make these loans, they will have to supply pounds in the foreign exchange market to obtain dollars. The increase in the supply of pounds results in depreciation of the pound and appreciation of the dollar. 5. Changes in Relative Expected Returns on Stocks, Real Estate, and Production Facilities- International investing extends beyond buying just foreign bonds. To make the investments, investors in one country must sell their currencies to purchase the foreign currencies needed for the foreign investments. Suppose investing in England suddenly becomes more popular due to a more positive outlook regarding expected returns on stocks, real estate, and production facilities there. U.S. investors will sell U.S. assets to buy more assets in England. U.S. investors will exchange their dollars for pounds, which are then used to purchase the British assets. The increased demand for pounds will cause it to appreciate and therefore the dollar will depreciate relative to the pound. 6. Speculation- Currency speculators are people who buy and sell currencies with an eye toward reselling or repurchasing them at a profit. Suppose speculators expect the U.S. economy to grow more rapidly than the British economy and to experience more rapid inflation as a result. These expectations translate into the anticipation that the pound will appreciate and the dollar will depreciate. Speculators who are holding dollars will therefore try to convert them into pounds. This effort will increase the demand for pounds and cause the dollar price of pounds to rise. A selffulfilling prophecy occurs. The pound appreciates and the dollar depreciates because speculators act on the belief that these changes will in fact take place. Table 38.2 has more illustrations of the determinants of exchange rates. Recent U.S. Trade Deficits As shown in figure 38.4a, the United States has experienced large and persistent trade deficits in recent years. These deficits rose rapidly between 2001 and 2006 before declining when consumers and businesses greatly curtailed their purchase of imports during the recession of 2007-2009. Economists expect the trade deficits to expand, absolutely and relatively, toward prerecession levels when the economy recovers and U.S. income and imports again rise. Causes of the Trade Deficits First, the U.S. economy expanded more rapidly between 2001 and 2007 than the economies of several U.S. trading partners. The strong income growth enabled Americans to greatly increase their purchases of imported products. Another factor explaining large trade deficits is the enormous U.S. trade imbalance with China. In 2007 the U.S. imported $257 billion more than it exported to China. The U.S. is China’s largest export market, and although China has greatly increased its imports from the U.S., its standard of living has not yet risen sufficiently for its households to afford large quantities of U.S. goods. Adding to the problem, China’s government has fixed the exchange rate of its currency, the yuan, to a basket of currencies that includes the U.S. dollar. Therefore, China’s large trade surpluses have not caused the yuan to appreciate much against the dollar. Another factor underlying the large U.S. trade deficits is a continuing trade deficit with oil-exporting nations, or OPEC. A declining savings rate has also contributed to the large trade deficits. Last Word: Speculation in Currency Markets