Activities of Living Model

advertisement

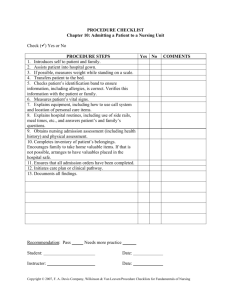

The Activities of Living Model and the Conceptual Systems Model: An Application to the Clinical Scenario Candice Kiskadden Clarion and Edinboro Universities Overview Introduction Both nursing models presented are grand nursing theories based on the interactive process. Each has relatable metaparadigm—although not intrinsically listed— and are similar in science, philosophy, and nursing (McEwen & Wills, 2011). However, differences between them give a unique perspective of nursing and health and how it relates to the individual. Each continues to be used in current nursing practice, with new evidence-based nursing models emerging from the framework of the prodigious authors and nursing educators. Current research continues to test and study each of the grand theories with agreeable results. In practice and in clinical scenario, the theories help define nursing care and the importance of action and interaction. The Theorists of Activities of Living Model Nancy Roper, Winifred Logan, and Alison Tierney collaborated together to build on Roper’s creation involving activities of living. The three developed the Activities of Living model as a structure for nursing students and educators. It is still commonly used today in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Europe, and the authors continue to review and revise the model to reflect current nursing practices. Nancy Roper Nancy Roper was a principal tutor at a nursing school in England until moving to Scotland during the 1960s where she was an editor for Churchill-Livingstone Publishers. Early in her nursing training, she did not like to be moved to various wards and felt that there were more commonalities than differences in nursing experiences, so she registered to pursue her MPhil degree at Edinburgh University and focused on the question, “What is nursing?” (Scott, 2004). By the early 1970s, she foreshadowed her future theory work with her thesis, “Clinical Experience on Nurse Education”, which eventually developed into her model (McEwen & Wills, 2011). Roper became the first nursing research officer at the Scottish Home and Health Department, working with the Chief Scientist and completing several short-term assignments for the World Health Organization’s Europe office. She was dedicated to nursing and continued to lecture worldwide until well into her eighties (Dopson, 2004). Winifred Logan Winifred Logan began her nursing education in Edinburgh, earning a degree from Colombia University in 1966, and serving in the Nursing Studies department at the University of Edinburgh throughout the 1960s and 70s. She was also the Nurse Education Officer in the Scottish Office and was the executive director of the International Counsel of Nurses, as well as a consultant for WHO in Malaysia, Iraq, and Europe (McEwen & Wills, 2011). Alison Tierney As one of the first nurses to earn a PhD in Great Britain, Tierney has been the Director of Nursing Research at the University of Edinburgh, eventually serving as Personal Chair in Nursing Research. Tierney has also served as Head of the Department of Clinical Nursing at the University of Adelaide in South Australia (“New nursing head”, 2003). The Activities of Living Model The Roper, Logan, and Tierney model developed from research conducted by Nancy Roper and was initially intended to be used as a tool for nursing students and nursing educators (Holland, Jenkins, Solomon & Whittam, 2008). Research involving clinical patients followed an extensive literature review and organization of commonplace and ordinary daily activities, which translated into the activities of living (AL) model. The model is divided into two components, the Model of Living and the Model of Nursing (McEwen & Wills, 2011). Major concepts of the Roper, Logan, and Tierney AL model include activities of living, lifespan, and the dependence/independence continuum, but the authors do not specifically define the metaparadigm concepts of nursing— human, health, nursing, and environment (McEwan & Wills, 2011). These concepts are described throughout the model in context. Person as described in the Model of Nursing is a “person” experiencing activities of living during the person’s lifespan (defined as infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age) as influenced by the five factors. Nursing is described as the profession in which assists the person with difficulties associated with the activities of living. Health is achieving and maintaining the optimal level of independence in every AL within the person, and the environment is contained within five factors that influence ALs (Holland et al., 2008). And finally, environment is the outside contingencies in which the person interacts (McEwen & Wills, 2011). Further, the model defines the five influential factors as: biological, psychological, sociocultural, environmental, and politico-economic (McEwen & Wills, 2011). Biological influences relate to the human body’s anatomical and physical performance as influenced by genetics. Biological influences can be a positive attribute, but also can be detrimental, such as the child predisposed to becoming a short-statured adult who is deprived of food and this exacerbates the growth and normal development. Psychological factors include emotional and intellectual development, and the eventual adult response from this development. Sociocultural factors encompass social class, expected cultural norms, and the difference and similarities between culture and religion. Environment within the five influences includes atmospheric components (sub-divided into organic and inorganic particles, light rays, and sound waves), clothing, household environment, vegetation, and buildings. Politicoeconomic is generally characterized by the realization that every person lives within a certain “state” and ALs can be influenced by this state, whether the person lives within a free country or one marked by danger from backlash and suppression (Holland et al., 2008). Holland et al. (2008) state that maintaining a safe environment is essential to stay alive and carry out the other ALs, and because of this, action is needed—either individually or through the nurse—to ensure safety. Examples of this attention to safety include driving carefully and washing hands after elimination. The authors of the model divide the ALs into 12 categories and evaluate each according to the five factors moving across the continuum from independence to dependence and throughout the lifespan of the “person” (McEwen & Wills, 2011). The 12 activities of the AL model Maintaining a safe environment Controlling body temperature Communicating Mobilizing Breathing Working and playing Eating and drinking Expressing sexuality Eliminating sleeping Personal cleansing and dressing Dying It is important to note that although the model examines each activity, one cannot be explored at the exclusion of another, as such, breathing cannot be explored without considering also sleeping or communicating (Holland et al., 2008). As individuals move across the lifespan, they experience different levels of independence and dependence of the 12 activities of living. Each of these experiences is also influenced by the five factors, such as psychological, and the nurse needs to use assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation skills to properly care for the person (McEwen & Wills, 2011). The Roper, Logan, and Tierney model of nursing is useful in nursing and the authors have stated that they hope that nurses will continue to use the model and refine, adapt, and incorporate it into their own practice. This assists in the testability of the model, which is the product of testing related to the core of living. It is also universal, so it is easily applied to develop middle range research theories. Finally, the model is economic in quality, equally utilized in two parallel models that appear initially elementary, but are actually intricate and complicated (McEwen & Wills, 2011). The Theorist Behind the Conceptual System In an educational path dear to my heart, Imogene M. King obtained her nursing diploma from St. John’s Hospital School of Nursing in St. Louis, Missouri in 1945. She then continued her education, obtaining her bachelor of science in nursing education in 1948 and her master of science in 1957 from St. Louis University. She completed her doctor of education degree from the Teachers College of Columbia University in 1961, and in 1980, she was awarded an honorary doctor of philosophy degree from Southern Illinois University. King has been awarded by the American Nurses Association (ANA) for contributions to nursing practice, education, and research as in 2004, was inducted into the ANA Hall of Fame. She was a 40-year participant to North American Nursing Diagnosis Association International, participating in the First National Conference on the Classification of Nursing Diagnoses. King has said that she derived her nursing theory from her experience as Director of the Outpatient Clinic at St. John’s Hospital from reflecting on her own interactions with patients, in essence, King’s theoretical development was practice driven (Lavin & Killeen, 2008). The Conceptual System Developed throughout the 1970s, King published her conceptual system and the Theory of Goal Attainment in 1981. From 1968 to 1972, Imogene King was working as the director of the School of Nursing at Ohio State University in Columbus, and while there, she wrote her 1971 book, Toward a Theory for Nursing: General Concepts of Human Behavior. In the book, King concluded that a “systematic representation” of nursing was needed to develop the science of nursing after more than a century of nursing art. Her book ultimately earned her the American Journal of Nursing Book of the year award in 1973 and became a precursor for her future nursing model (Alligood & Tomey, 2010). King acknowledged the underpinnings of her theory to the von Bertalanffy General Systems Model, stating that her hope was to study the complexity of nursing “as an organized whole” (McEwen & Wills). The General Systems model was developed as a biological theory, but has basis in economics and social sciences as a model to develop sets of complex interacting elements and that the system would be “a whole that functions as a whole by virtue of the interaction of its parts” (Department of Theoretical Biology). This theory is similar to the nursing view of the individual as a whole, not just a sum of systems. According to Sieloff-Evans (1991), King examined society and was able to identify several trends in health care; she recognized that the environment in healthcare was becoming increasingly complex. With this information, she developed many questions related to nursing, asking what is the nursing act, process, and goal. She also wanted the definition of nurses and their education and practice. And finally, with relation to this changing environment, King wanted to know, “Who needs nursing in this society?” Psychology, sociology, and nursing literature reviews led King to note consistent wording, and from this, she developed three initial concepts: interpersonal relations, perception, and organization. Additionally, she identified another word—energy—as an integral part of the other words (Sieloff-Evans, 1991). King realized that she needed to provide a “structure for nursing as a discipline and as a profession, and in this attempt, she also developed the necessary function, resources, and goals. She defined structure as a reflection of the person interacting with their environment; function as the scientific process: viewing, recognizing, observing, measuring, synthesizing, interpreting, and analyzing, but conducted simultaneously within the context of the nursing process. Her resources involved both human and material objects, and her goal for the system was health. Utilizing this conceptual framework, she identified three “dynamic interacting systems”: personal, interpersonal, and social (Sieloff-Evans, 1991). After an extensive review of 20 years of nursing literature, King identified several concepts relevant to nursing practice: Authority Status Power Growth and development Body image Interaction Role Stress Communication Organization Self Time Decision making Perception Space Transaction King stated that the three systems and above concepts create a vehicle for nurses to organize “knowledge, skills, and values” (Sieloff-Evans, 1991). The personal system as defined by King focuses on people as individuals, but the whole individual is important. The above concepts applicable to the personal system would include body image, perception, space, self, growth and development, and time. Individuals have awareness, are able to make decisions based on events around them and are able to identify means in which to achieve goals. King’s interpersonal systems includes any group of two up to large assemblages of people; the group’s variability and complexity increase synchronously with its size. The above concepts relative to interpersonal systems include communication, roles, interaction, stress, and transaction. The nursing process generally manifests within the interpersonal system. King describes the nursing process as action, reaction, interaction, and transaction between nurse and patient (Sieloff-Evans, 1991). Generally speaking, the nursing process is where the “action” takes place. Similar to the definition of family or community, King characterizes social systems as a boundary system of social roles, behaviors, and practices established to maintain values and regulate rules (Alligood & Tomey, 2010). King also contends in her theory that common goals interests are shared within a social system between individuals. Sieloff-Evans (1991) depicts work places, religions, educational systems, families, and healthcare settings as examples of social systems. King specifically attributed several common characteristics to social systems: authority, decision making, organization, power, and status as particularly relevant. She felt it was important for nurses to know the social systems’ impact on groups and individual patient’s behaviors. With “the establishment of mutually set goals”, patients and nurses must work together in the planning and evaluation of outcomes (Sieloff-Evans, 1991). Major concepts illustrated by King include health, nursing, and self, and by default, environment by means of the exchange of each with external environmental factors. In her theory, she defines health as the “dynamic” life experiences of individuals in reaction to environmental influences such as stressors, and the “optimum” use of resources to reach full potential for daily living. Nursing is described as the “process of action, reaction, and interaction” and the sharing of information between nurse and patient about the nursing situation. And finally, self is represented as the awareness on an individual’s own existence as a whole person (Alligood & Tomey). A Comparison of Activities of Living and the Conceptual System Models Although both the AL and Conceptual Systems models are based on the interactive process, they are unique in philosophy. Generally, grand nursing theories have defined metaparadigm: person, nursing, health, and environment. The Roper, Logan, and Tierney AL model has no defined metaparadigm, instead infers these qualities through the context of the model, whereas King has clear definitions of health, nursing, and self, but person and environment are intuitive within the model. A visual comparison of the two models further demonstrates the differences of focus within each model. The AL model developed by Roper, Logan, and Tierney uses a more linear extraction for information and content. The Activities of Living model and the Conceptual Systems model. The Conceptual Systems model, conversely, has a cyclical appearance representing the influence and interaction within the personal, interpersonal, and social systems. Where the linear presentation of the AL model well-represents the linear focus on lifespan, independence, and dependence, the circular focus in King’s model epitomizes the encompassing systems. Despite these disparities, the two models are similar in nursing application. Both models rely on actions within the model. King’s Conceptual Systems frequently uses “action”: her defined nursing process includes “action, reaction, interaction, and transaction” (Alligood & Tomey, 2010). Similarly, Roper, Logan, and Tierney use “action” as action is needed to carry out the activities of living. Each theory also is testable, as evidenced by continued review, revision, and redevelopment by the respective authors. Both the AL and Conceptual Systems theories are still used widely today by nursing students, nursing educators and clinical nurses. Each is still very relevant to practice and is applicable enough for nurses to utilize each in daily practice. Current Clinical Literature To further demonstrate the advancement of evidence-based practice utilizing the AL and Conceptual Systems theories, two scholarly articles will be included. The authors of the first article, “Using the Roper-Logan_Tierney model in neonatal transport” critique the theory applied to the nursing care of a neonate, Jonathon, born at 28 weeks gestation. Healy and Timmins (2003) first reveal and discuss the major components of the AL model and the factors that influence these activities of living. They continue with a detailed assessment of Jonathon, the neonate, using the AL theory and relate the assessment findings as actual problems or potential problems. Within their conclusion, Healy and Timmins (2003) state that the AL theory provided a “clear framework” to guide care given to Jonathon and his family. The authors do note, however, that the development of nursing care plans should be clinically driven and modified based on suitability to the individual patient. The authors clearly demonstrate the current applicability of the AL model to modern nursing. They were able to easily adapt the model to meet the needs of the neonate in the case study with favorable results. With this supposition, clinical nurses need to be aware of the need to also utilize clinical nursing care plans that are reviewed and modified often. The second article is a viewpoint of King’s Conceptual Systems and the use in nursing informatics and global nursing classification systems authored by Mary Killeen and Imogene King. With the advent of the Internet, communications worldwide are becoming more accessible and more transparent. Change is occurring rapidly in the fields of technology and nursing, so it is prudent for nurses to use technology to their advantage. Nursing Informatics is a growing field, as with the mandate of electronic patient charting, eventually all nurses will be affected by these rapid progressions in the Information Age. Killeen and King (2007) apply King’s Conceptual System theory as well as her Theory of Goal Attainment to address the unique needs of Nursing Informatics. The authors present King’s theory as background information and state that currently, nursing informatics is not based on nursing theory. Killeen and King (2007) affirm the definition of nursing informatics as “a combination of computer science, information science, and nursing science designed to assist in the management and processing of nursing data, information, and knowledge to support the the practice of nursing and delivery of nursing care”. Interestingly, the authors also allege that informatics is not using nursing’s knowledge as it should. The authors also discuss the nursing process for technology use and discuss the critical need for mutual goalsetting, as utilized in King’s Conceptual System theory. As a conclusion, Killeen and King (2007) provide substantial data to relate to the nursing process and evidence-based care by using the Conceptual System theory (as well as the Theory of Goal Attainment) and present a current nursing standard. Although this approach to King’s model is somewhat more complex and abstract, the usefulness of the theory is well-evidenced. As the authors state at the beginning of the article, King’s Conceptual System theory is able to be adapted to nearly any situation encompassing individual interactions of humans to achieve goals (Killeen & King, 2007). Because the theory is not directly related to patient care by the authors, they tend to take the “person” out of the equation, and even though nursing informatics will in some manner affect patients, it is not directly influential. Using the information from this article, nurses could develop structured models for informatics, but not necessarily for patient care. Patient care is what will be discussed next. A Clinical Scenario The presented clinical scenario occurred when I was a relatively young and new nurse working on an Ortho/Neuro/Trauma floor. I cared for a young man named Chris, who was close to my age and had come to the emergency room from a traumatic motor vehicle accident (MVA). He had a head injury and a tracheostomy as well as multiple trauma issues of which I no longer remember the specifics. He could not talk to me, and as a patient with a head injury, his thought processes were often altered. I cared for him almost every day for about three weeks. He was not from the area because he had attended a local University and was residing at school at the time of the accident. The hospital near his home was not equipped to handle a trauma patient, so he remained on my unit. We walked and walked and walked the halls (typical for some head injuries), and I would simply talk to him: what I had watched on TV, or what I had read about Penn State (his University), or other little things that someone his age may be interested in. He could not respond back, mainly due to the tracheostomy, but he would nod his head sometimes or use hand gestures. We would continue to walk and talk all night, as long as my other duties would let me. Eventually, he moved to a rehab closer to his parents’ home. It was great to discharge him, I felt as though he had made great progress in the weeks that he was on our unit. It was not until the end of next summer when he stopped by to visit that I really felt that I had made a difference. He was returning to school and wanted to say thanks to me for my companionship when he was a patient. His mother hugged me, he hugged me several times, and I cried. I could not help it; it was such an emotional event to see this young man who could not even talk to me less than a year ago excited to tell me all about returning to school. He was so grateful that I was simply willing to walk—literally miles—with him. I really felt that I had made a difference in his life, and it was not for the great care of his chest tube when he first arrived, or his complex dressing changes, or anything that nurses typically think of good care. It was the simple act of walking with him and talking to him, even if he could not respond verbally. I personally had made a huge difference to him for something that seemed so small at the time. I have cared for thousands of patients since his stay at the hospital, but he still remains as a big impression in my mind, all because I was able to give him the compassion that he needed. Implications for AL and Conceptual Systems Theories in the Clinical Scenario The choice of the AL and Conceptual Systems theories was purposeful in relation to my clinical scenario of my patient with the traumatic head injury. Most outstanding is the use of the AL model in relation to his daily activities and where he rested on the lifespan and dependence/independence continuums. Chris was a young, vibrant individual who had cared for himself until the MVA. It was now my responsibility as the nurse to properly assess his activities of living and develop an appropriate plan of care for him. Also, in relation to his needs and care, King’s Conceptual Systems model is very appropriate, especially when utilizing the concepts within the theory. Chris’s self-image was suddenly changed with multiple traumas and a tracheostomy. He needed to rely on nursing staff to help meet his needs, using action, reaction, and interaction. As Chris’s nurse, I could perform an action such as attempting to communicate, he would have a reaction to my attempt, and we would have an interaction based on this frequent cycle. Also, because Chris was isolated from his family and friends for the majority of his hospitalization and he was in the controlled environment of inpatient care, nursing staff could easily influence his behavior and actions. Although not every aspect of the AL and Conceptual Systems theories applies to Chris’s clinical situation, both are interactive process theories based on interpersonal interactions. The conceptual framework for King’s theory easily applies to the situation because of the human factor. Nurses need to be aware of the complex dynamics of individuals whom they treat, and by realizing that Chris simply needed some cohort company, I was able to meet his goal of interaction. The Activities of Living that Chris suddenly found himself in need of were a complex, intrinsic part of who he was as a “whole” individual. He was not simply a broken bone or a collapsed lung; he was more than simply the sum of his parts. Recognizing that Chris was a whole person and needed to be treated holistically gave me the insight to care for his emotional well-being as well as his physical well-being. References Alligood, M., & Tomey, A. (2010). Nursing theorists and their work. (Seventh ed.). Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier. Department of Theoretical Biology. (n.d.). General system theory. Retrieved from http://www.bertalanffy.org/system-theory/general-system-theory Dopson, L. (2004, October 15). Nancy Roper, author of a model for nursing. The Independent. Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/nancy-roper Healy, P., & Timmins, F. (2003). Using the Roper-Logan-Tierney model in neonatal transport. British Journal of Nursing, 12(13), 792-798. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com Killeen, M. B., & King, I. M. (2007). Viewpoint: Use of King’s Conceptual System, Nursing Informatics, and nursing classification systems for global communication. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 18(2), 81-87. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com Sieloff-Evans, C. L. (1991). Imogene King: A conceptual framework for nursing. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Holland, K., Jenkins, J., Solomon, J., & Whittam, S. (2008). Applying the Roper-Logan-Tierney model in practice. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill-Livingstone Elsevier. Lavin, M. A., & Killeen, M. B. (2008). Tribute to Imogene King. International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications, 19(2), 44-47. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com McEwan, M., & Wills, E. M. (2011). Theoretical Basis for Nursing (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. New nursing head has distinguished career. (2003, January 15). Retrieved from http://www.adelaide.edu.au/news/news454.html Scott, H. (2004). Nancy Roper (1918-2004): a great nursing pioneer. British Journal of Nursing, 13(9), 1121. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com