Questions

advertisement

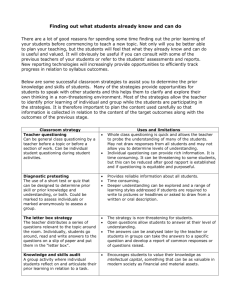

Developing the Questioning Mind The Quality Of Our Thinking is Given in The Quality of Our Questions It is not possible to be a good thinker and a poor questioner. Questions define tasks, express problems, and delineate issues. They drive thinking forward. How Many People Have Seriously Considered Important Questions Related to Their Thinking? What have I learned about how I think? Have I ever studied my thinking? What information do I have, for example, about the intellectual processes involved in thinking? What do I really know about how to analyze, evaluate, or reconstruct my thinking? Where does my thinking come from? How much of it is of high quality? How much of it is of poor quality? How much of my thinking is vague, muddled, inconsistent, inaccurate, illogical, or superficial? Am I, in any real sense, in control of my thinking? Do I know how to test it? Do I have any conscious standards for determining when I am thinking well and when I am thinking poorly? Have I ever discovered a significant problem in my thinking and then changed it by a conscious act of will? If anyone asked me to teach him or her what I have learned about thinking thus far in my life, would I have any idea what that was or how I learned it? 6.1 Think for Yourself: Questioning Your Questions Answer this question: What are the questions you would most like to answer? Once you have a short list of three or four, answer these questions: Where are these questions taking you? How is your focus on these questions affecting your behavior, your emotions, your experience, and the quality of your life? For example, too much emphasis on the question, “How can I get the content covered in the small amount of time I have in my classes?” may lead you to miss the significance of this question, “What does it mean to be an educated person and am I helping my students become educated?” Disciplined Questioning transforms the mind To Develop Skills of Questioning: we need theory. we need to think important ideas into our thinking. Eight Questions Students Can Routinely Ask when They Have Constructed the Concept of the Elements of Reasoning In Their Thinking 1. What is the main purpose of the reasoning? 2. What are the key issues, problems, and questions being addressed? 3. What is the most important information being used? 4. What main inferences are embedded in the reasoning? 5. What are the key concepts guiding the reasoning? 6. What assumptions are being used? 7. What are the positive and negative implications? 8. What point of view is/should be represented? Questions Students Can Routinely Ask In Order to Assess Thinking Questions Focused on the Intellectual Standards Work in pairs. Use Questions Guide. Take turns reading aloud the sections with questions related to the intellectual standards on pp. 22-23. After you read each section, discuss how important this standard is to your discipline/subject, and how you might foster student questioning focused on that standard. Discuss in pairs To what extent are you currently teaching students to analyze and assess reasoning by asking questions focused on the elements of reasoning and intellectual standards? How can you foster student questioning using the elements and standards? Disciplined Questioners Develop Tools for Questioning For every important concept, there are questions implied by that concept. For every well-reasoned theory, there are important questions implied by that theory. Examples: Anna Freud’s defense mechanisms, Theory of Evolution Formulate Questions Guided By Theories in Your Discipline Make a short list of theories used in your discipline or subject. Then choose one of these theories. Make a list of questions you can ask when you understand the theory. Three of the most distinguished thinkers in history had in common, not inexplicable genius, but a questioning mind Isaac Newton At the age of 19 Newton drew up a list of questions under 45 headings. His title, Quaestiones, signaled his goal: to constantly question the nature of matter, place, time, and motion. He worked hard to understand the thinking of others working on his list of problems. For example, he bought Descartes' Geometry and read it by himself. After two or three pages, when he could understand no further, “he began again and advanced farther and continued doing so till he made himself master of the whole.” Newton said: “I don’t know what I many seem to the world, but, as to myself, I seem to have been only a boy playing on the sea shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” Charles Darwin “I have never been able to remember for more than a few days a single date or line of poetry.” Instead, he had “the patience to reflect or ponder for any number of years over any unexplained problem…At no time am I a quick thinker or writer: whatever I have done in science has solely been by pondering, patience, and industry.” Albert Einstein Einstein failed his entrance exam to Zurich Polytechnic. When he finally passed (by attending a cram school) he did not want to think about scientific problems for a year. His final exam was so non-distinguished that afterward he was refused a post as an assistant. Einstein said that his schooling required, “the obedience of a corpse.” The effect of the regimented school was a clear-cut reaction; he learned “to question and doubt.” Einstein said of himself: “I have no particular talent. I am merely extremely inquisitive.” Students Need the Tools of Critical Thinking to Develop a Questioning Mind, a mind that continues to transform itself through the questions it asks. Distinguishing Questions of Fact, Preference and Judgment In pairs, take turns reading pp. 8-9 in Questions Guide. Make a list of your own questions in each category. Three Types of Questions 3 Conflicting Systems 1 One System 2 No System Require evidence and reasoning within a system call for stating a subjective preference Require evidence and reasoning within multiple systems a subjective opinion better and worse answers cannot be assessed judgment a correct answer knowledge To Determine Which of These Three Types of Questions We Are Dealing With (in Any Given Case) We Can Ask the Following Questions: Are there relevant facts we need to consider? If yes, then either the facts alone settle the question (and we are dealing with a question of procedure), or the facts can be interpreted in different ways (and the question is debatable). If there are no facts to consider, then it is a matter of personal preference. If the facts settle the question, then it is a “one-system” procedural question. Categorize These Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. How many people are in the room? What is the chemical constitution of table salt? What is the most significant medical problem facing the country today? What philosophy of nursing makes best sense, given the present conditions of nursing? Are we losing the war on cancer? What is the unemployment rate now in Georgia? What is the best way to live a healthy and fit life? Is secondary smoke a health hazard? What is the best way to bring peace to the Middle East? Formulate Questions of Judgment in Your Subject or Discipline Make a list of questions of judgment within your discipline, or within a subject you teach. Discuss What is your understanding of prior questions and domains within questions? How can understanding this theory help you approach complex questions? Choose one of your questions Discuss with your partner: What domains are inherent in your questions? What are some of the questions you would have to answer before you answered the complex question? Identifying Prior Questions Read page 16 with a partner and discuss. Now choose one question on your list. Working alone, make a list of questions one would have to answer before answering the original question. Asking Complex Interdisciplinary Questions Students need practice in reasoning through complex interdisciplinary questions. Working with a partner, together read through pages 17-18 in the Asking Essential Questions guide. Discuss your understanding of the content. Fostering Students’ Abilities to Reason Through Complex Interdisciplinary Questions Make a list of interdisciplinary questions you might have students reason through, questions which include a dimension within your discipline, as well as dimensions within other disciplines. Identifying Domains Within Complex Questions Now choose one question from your list. Write out the domains embedded in the question and some important questions within each domain one would have to reason through before attempting to answer the question. You should focus on a question you would want students to be able to reason through. Refer to pages 17-18. Understanding the Foundations of Ethical Reasoning Work with a partner. Person A reads pp. 28-29 (to middle of the page) Person B reads the rest of p. 29-30. Take notes in order to teach to your partner. Then teach to your partner using only your notes. Identifying Ethical Dimensions of Questions Make a list of ethical questions you would want your students to reason through, or questions with an ethical component. Then make a list of prior questions for that questions – questions one would have to answer before answering that question. Understanding Foundational Questions Within a Discipline Working alone, read pp. 35-37 Then make a list of foundational questions within one subject or discipline you teach. Reasoning Through Complex Conceptual Questions In pairs, read pp. 11-12 in Questions guide. Discuss your understanding of simple and complex conceptual questions. Read p. 13 together and discuss the four conceptual tools. Together, choose one complex conceptual question on p. 12 and formulate at least one example of each type of case discussed on p. 13 for the question you have chosen. Then complete the process outlined at the bottom of p. 14. Questions that develop the mind emerge out of theory about the mind and how it operates Questioning assumptions and implications Questions can lead in many directions Questioning questions Questioning the quality of thinking Questioning concepts Questioning the logic of thinking