African Trade Cities

advertisement

Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani was once the most famous trading post in East Africa. In the 9th century the wealthy Swahili owner of

the island sold it to a trader called Ali bin Al-Hasan, the founder of Shiraz Dynasty. From the 11th Century to early

15th Ali bin Al-Hasan managed to create a powerful city (Kilwa Kisiwani) and as major trading center along east

African coast. He built a great mosque, and established close trading links to interior of southern Africa as far as

Nyasaland and Zimbabwe.

In this sense, Kilwa Kisiwani became the principle trading port on the Indian Ocean. Its wealth came from the

exchange of gold and iron (from Great Zimbabwe and other part of Southern Africa), ivory and slaves (from mainland

Tanzania), with textiles, jewelry, porcelain and spices from Asia.

By the 13th Century Kilwa had become the most powerful city on the East African Coast, exercising political and

trading domination as far as Pemba Island in the north and Sofara (the modern Beira in Mozambique) in the south.

It’s offshore location and the tidal currents that isolate the island from the mainland protected them from a landbased attack.

The outside world came to know Kilwa through a Moroccan intellectual travel {Abu Abdullah Ibn Batuta} who had

visited Kilwa in 1331, and the Portuguese sailors who visited the place about 170 years after Battuta. These travelers

are credited with much of Kilwa's written History – about the life, wealth and powerful trade control on East African

Coast. When Abu Abdullah Ibn Batuta, arrived at Kilwa, he was amazed with its beauty.

"The city large and elegant, its buildings, as typical along the coast, constructed of stones and coral rag. Houses

were generally single storied, consisting of a number of small rooms separated by thick walls supporting heavy

stone roofing slabs laid across mangrove poles.

Some of the more formidable structures contained second and third stories, and many were embellished with cut

stone decorative borders framing the entranceway. Tapestries and ornamental niches covered the walls and the

floors were carpeted. Of course, such appointments were only for the wealthy; the poorer classes occupied the

timeless mud and straw huts of Africa, their robes a simple loincloth, their dinner millet porridge".

By the late 15th Century, Kilwa's fortunes changed. The Portuguese conquered the island after one of their explorers,

Pedro Alvares Cabral, visited Kilwa and reported seeing beautiful houses made of coral stones and terraces of "black

moors" as Vasco da Gama called it when he passed the island. In 1505 Portuguese established full control of the island

with intention of taking absolute control of the lucrative Indian Ocean trade. They built a garrison and established a

strong trading post with Sofara.

Today Kilwa has managed to preserve much of the scenery that attracted Ibn Batuta, Pedro Alvares Cabral, and Vasco

da Gama. To preserve its beauty UNESCO declared Kilwa a World Heritage Site in 1981. The island is separated from

the mainland by a 3 km-wide channel. Visitors should expect to see medieval ruins including a mosque, considered to

be (at that time) the largest in East African Coast. It has domed chambers, monolithic pillars, water tanks, and slabs for

prayers, and the Great House, which is believed to be the house of an Iman or Sultan.

http://www.utalii.com/Off_the_normal_path/kilwa.htm

Once a burgeoning empire, the biggest

and most powerful on the East African

Coast, the Kilwa Kisiwani – ‘isle of the

fishes’ – now stands in ruins, its

labyrinthine pathways, grand palaces

and majestic mosques completely

abandoned, stripped of their former

beauty. Take a walk through Kilwa’s

amazing history and discover the

incredible wealth that once inhabited its

walls.

‘The city comes down to the shore, and

is entirely surrounded by a wall and

towers, within which there are maybe

12,000 inhabitants. The county all round

is very luxurious with many trees and

gardens of all sorts of vegetables,

citrons, lemons, the best sweet oranges

that were ever seen…’ So wrote

Gaspar Correia, 16th century Portuguese soldier and historian, about the island of Kilwa. Only a few years before, circa

1502, his countryman Vasco de Gama – the first European to reach India by sea – had forced Kilwa’s Sultan to pay

tribute in gold. So much gold, in fact, that some of it can still be seen in Lisbon, forged into an ornate pyx [box for the

Eucharist bread] for the Jéronimos Monastery. In 1505, a Portuguese force led by Francisco de Almeida built a fortress

on the isle, and the prosperous city began a protracted decline. Although recaptured by an Arab prince in 1512, growing

Western dominance of the trade routes stemmed the island’s wealth, while successive conquests by Omani, French and

German forces clipped its power.

The Beginnings of an Empire

The Kilwa Sultanate began in the 10th century. Ali ibn al-Hassan was the son of Emir of Shiraz and an Abyssinian slave.

Caught in an inheritance battle with his six brothers, Ali fled his homeland with his Persian entourage. He settled on the

island, then inhabited by indigenous Bantu people, and began constructing his own city. Legend claims that he bought

Kilwa from a local king, who exchanged it for enough cloth to encircle the island. The king quickly changed his mind, but

Ali had already destroyed the narrow land bridge that connected Kilwa to the mainland, securing it for himself.

Ali’s Shirazi dynasty ruled until a succession crisis in 1277, after which the related Mahdali sultans took over. During

these first three centuries, several of the buildings whose ruins survive were built. The Great Mosque, the oldest extant

in the region, was begun in the 1100s and expanded repeatedly afterwards. It has an ornate roof with 16 domes,

supported by an astonishingly complex system of arches and pillars. The central dome, now lost, was the largest in East

Africa until the 19th century. When the great Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited in 1331, he was struck by the

mosque’s splendour and described the city as ‘fine and substantially built.’ Smaller mosques are scattered across Kilwa,

each with their own distinct features. The Jangwani Mosque has distinctive water-holders set into its walls to allow

worshippers to purify themselves for prayer, while a nameless small mosque – perhaps the city’s most pristine surviving

structure – is attached to what is believed to be a madrasa [religious school].

The majority of the isle’s ruins date from the 14th and early 15th centuries, when the sultanate was at the zenith of its

power. Kilwa had become one of the Indian Ocean’s mercantile capitals, and its wealthy residents built grandiose coral

dwellings. The Great House is said to have been owned by a sultan, who is alleged to be buried in one of the four tombs.

The Makutini Palace, likely the most imposing on the island, is a robust triangular structure, built in the 15th century as

the sultan’s stronghold. Pass through its starkly grand towers and you’ll find another sultan’s grave. The Gereza, a

fortress on the island’s tip, has elegant crenellation and a vast wooden portal. Most striking of all, however, is the

Husuni Kubwa or ‘Queen’s House’. Perched atop a cliff, about a mile from the main cluster of ruins, it is reckoned to be

the largest pre-colonial building in sub-Saharan

Africa. Within, you’ll find the remains of an 18domed mosque, an octagonal swimming pool, a

vast tiered hall and an array of courtyards. All in

all, the complex houses over 100 rooms.

When the conquistadors arrived in 1502, the city

was the most powerful on the East African coast,

with an empire stretching north to south from

Malindi in present-day Kenya to Cape Correntes in

Mozambique. Its sultans even controlled outposts

on Madagascar. Commerce made it mighty. Ships

brought in porcelain from China, quartz from

Arabia and carnelians from India. Gold and ivory

came from Great Zimbabwe in the interior. Spices

and perfume were in the air, pearls, pottery and

tortoise shell in the market. Kilwa was the

principal gateway between Africa

and Asia, the Western end of the Indian Ocean

trading routes.

Map of Kilwa | © Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg (1527)

By Joe Lloyd

http://www.theculturetrip.com/africa/tanzania/articles/kilwa-kisiwani-the-ruins-of-east-africa-s-greatest-empire/

These broken pieces of pots were found on the shores

of Kilwa Kiswani, an island off Tanzania, which was once

home to a major medieval African port. The pale green

porcelain pieces are from China, the dark green and

blue pieces come from the Persian Gulf and the brown

unglazed pieces were made in East Africa. This rubbish

reveals a complex trade network that spread across the

Indian Ocean, centuries before the European maritime

empires of Spain, Portugal and Britain.

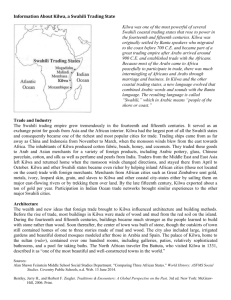

From around AD 800, merchants from Africa, the

Middle East, India, and later even China flocked to the

East African ports of Kilwa and Mombasa, which quickly

grew into wealthy cities. These merchants traded in

pots, spices, ivory, gems, wood, metal and slaves. A

new language, Swahili, developed in this multi-cultural environment, combining existing African languages with Arabic.

Islam was adopted as the religion in these ports, perhaps to aid in trade relations with the Middle East and also to

protect African merchants from being enslaved by other Muslims.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/1HzhZH2YTMWUgqXXFvhAeQ