Was Walt Disney Racist?

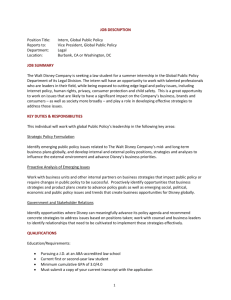

advertisement

Walt Disney, Biography Written by Brad A. Try to imagine a world without Walt Disney. A world without his magic, whimsy, and optimism. Walt Disney transformed the entertainment industry, into what we know today. He pioneered the fields of animation, and found new ways to teach, and educate. Walt's optimism came from his unique ability to see the entire picture. His views and visions, came from the fond memory of yesteryear, and persistence for the future. Walt loved history. As a result of this, he didn't give technology to us piece by piece, he connected it to his ongoing mission of making life more enjoyable, and fun. Walt was our bridge from the past to the future. During his 43-year Hollywood career, which spanned the development of the motion picture industry as a modern American art, Walter Elias Disney established himself and his innovations as a genuine part of Americana. A pioneer and innovator, and the possessor of one of the most fertile and unique imaginations the world has ever known. Walt Disney could take the dreams of America, and make them come true. He was a creator, a imaginative, and aesthetic person. Even thirty years after his death, we still continue to grasp his ideas, and his creations, remembering him for everything he's done for us. Walter Elias Disney was born on December 5, 1901 in Chicago Illinois, to his father, Elias Disney, an Irish-Canadian, and his mother, Flora Call Disney, who was of German-American descent. Walt was one of five children, four boys and a girl. Later, after Walt's birth, the Disney family moved to Marceline, Missouri. Walt lived out most of his childhood here. Walt had a very early interest in drawing, and art. When he was seven years old, he sold small sketches, and drawings to nearby neighbors. Instead of doing his school work Walt doodled pictures of animals, and nature. His knack for creating enduring art forms took shape when he talked his sister, Ruth, into helping him paint the side of the family's house with tar. Close to the Disney family farm, there were Santa Fe Railroad tracks that crossed the countryside. Often Walt would put his ear against the tracks, to listen for approaching trains. Walt's uncle, Mike Martin, was a train engineer who worked the route between Fort Madison, Iowa, and Marceline. Walt later worked a summer job with the railroad, selling newspapers, popcorn, and sodas to travelers. During his life Walt would often try to recapture the freedom he felt when aboard those trains, by building his own miniature train set. Then building a 1/8-scale backyard railroad, the Carolwood Pacific or Lilly Bell. Besides his other interests, Walt attended McKinley High School in Chicago. There, Disney divided his attention between drawing and photography, and contributing to the school paper. At night he attended the Academy of Fine Arts, to better his drawing abilities. Walt discovered his first movie house on Marceline's Main Street. There he saw a dramatic black-and-white recreation of the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ. During these "carefree years" of country living young Walt began to love, and appreciate nature and wildlife, and family and community, which were a large part of agrarian living. Though his father could be quite stern, and often there was little money, Walt was encouraged by his mother, and older brother, Roy. Even after the Disney family moved to Kansas City, Walt continued to develop and flourish in his talent for artistic drawing. Besides drawing, Walt had picked up a knack for acting and performing. At school he began to entertain his friends by imitating his silent screen hero, Charlie Chaplin. At his teachers invitation, Walt would tell his classmates stories, while illustrating on the chalk board. Later on, against his fathers permission, Walt would sneak out of the house at night to perform comical skits at local theaters. During the fall of 1918, Disney attempted to enlist for military service. Rejected because he was under age, only sixteen years old at the time. Instead, Walt joined the Red Cross and was sent overseas to France, where he spent a year driving an ambulance and chauffeuring Red Cross officials. His ambulance was covered from stem to stern, not with stock camouflage, but with Disney cartoons. Once he returned from France, he wanted to pursue a career in commercial art, which soon lead to his experiments in animation. He began producing short animated films for local businesses, in Kansas City. By the time Walt had started to create The Alice Comedies, which was about a real girl and her adventures in an animated world, Walt ran out of money, and his company Laugh-O-Grams went bankrupted. Instead of giving up, Walt packed his suitcase and with his unfinished print of The Alice Comedies in hand, headed for Hollywood to start a new business. He was not yet twenty-two. The early flop of The Alice Comedies inoculated Walt against fear of failure; he had risked it all three or four times in his life. Walt's brother, Roy O. Disney, was already in California, with an immense amount of sympathy and encouragement, and $250. Pooling their resources, they borrowed an additional $500, and set up shop in their uncle's garage. Soon, they received an order from New York for the first Alice in Cartoonland(The Alice Comedies) featurette, and the brothers expanded their production operation to the rear of a Hollywood real estate office. It was Walt's enthusiasm and faith in himself, and others, that took him straight to the top of Hollywood society. Although, Walt wasn't the typical Hollywood mogul. Instead of socializing with the "who's who" of the Hollywood entertainment industry, he would stay home and have dinner with his wife, Lillian, and his daughters, Diane and Sharon. In fact, socializing was a bit boring to Walt Disney. Usually he would dominate a conversation, and hold listeners spellbound as he described his latest dreams or ventures. The people that where close to Walt were those who lived with him, and his ideas, or both. On July 13, 1925, Walt married one of his first employees, Lillian Bounds, in Lewiston, Idaho. Later on they would be blessed with two daughters, Diane and Sharon . Three years after Walt and Lilly wed, Walt created a new animated character, Mickey Mouse. His talents were first used in a silent cartoon entitled Plane Crazy. However, before the cartoon could be released, sound was introduced upon the motion picture industry. Thus, Mickey Mouse made his screen debut in Steamboat Willie, the world's first synchronized sound cartoon, which premiered at the Colony Theater in New York on November 18, 1928. Walt's drive to perfect the art of animation was endless. Technicolor was introduced to animation during the production of his Silly Symphonies Cartoon Features. Walt Disney held the patent for Technicolor for two years, allowing him to make the only color cartoons. In 1932, the production entitled Flowers and Trees won Walt the first of his studio's Academy Awards. In 1937, he released The Old Mill, the first short subject to utilize the multi-plane camera technique. On December 21, 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first full-length animated musical feature, premiered at the Carthay Theater in Los Angeles. The film produced at the unheard cost of $1,499,000 during the depths of the Depression, the film is still considered one of the great feats and imperishable monuments of the motion picture industry. During the next five years, Walt Disney Studios completed other full-length animated classics such as Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi. Walt rarely showed emotion, though he did have a temper that would blow over as it blew up. At home, he was affectionate and understanding. He gave love by being interested, involved, and always there for his family and friends. Walt's daughter, Diane Disney Miller, once said: Daddy never missed a father's function no matter how I discounted it. I'd say,"Oh, Daddy, you don't need to come. It's just some stupid thing." But he'd always be there, on time. Probably the most painful time of Walt's private life, was the accidental death of his mother in 1938. After the great success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt and Roy bought their parents, Elias and Flora Disney, a home close to the studios. Less than a month later Flora died of asphyxiation caused by a faulty furnace in the new home. The terrible guilt of this haunted Walt for the rest of his life. In 1940, construction was completed on the Burbank Studio, and Disney's staff swelled to more than 1,000 artists, animators, story men, and technicians. Although, because of World War II 94 percent of the Disney facilities were engaged in special government work, including the production of training and propaganda films for the armed services, as well as health films which are still shown through-out the world by the U.S. State Department. The remainder of his efforts were devoted to the production of comedy short subjects, deemed highly essential to civilian and military morale. Disney's 1945 feature, the musical The Three Caballeros, combined live action with the cartoon animation, a process he used successfully in such other features as Song of the South and the highly acclaimed Mary Poppins. In all, more than 100 features were produced by his studio. Walt's inquisitive mind and keen sense for education through entertainment resulted in the award-winning True-Life Adventure series. Through such films as The Living Desert, The Vanishing Prairie, The African Lion, and White Wilderness, Disney brought fascinating insights into the world of wild animals and taught the importance of conserving our nation's outdoor heritage. Walt Disney's dream of a clean, and organized amusement park, came true, as Disneyland Park opened in 1955. As a fabulous $17-million magic kingdom, soon had increased its investment tenfold, and by the beginning of its second quarter-century, had entertained more than 200 million people, including presidents, kings and queens, and royalty from all over the globe. A pioneer in the field of television programming, Disney began television production in 1954, and was among the first to present full-color programming with his Wonderful World of Color in 1961. The Mickey Mouse Club was a popular favorite in the 1950s. But that was only the beginning. In 1965, Walt Disney turned his attention toward the problem of improving the quality of urban life in America. He personally directed the design of an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT). It was planned as a living showcase for the creativity of American industry. Disney said this about EPCOT: I don't believe there is a challenge anywhere in the world that is more important to people everywhere than finding the solutions to the problems of our cities. But where do we begin? Well, we're convinced we must start with the public need. And the need is not just for curing the old ills of old cities. We think the need is for starting from scratch on virgin land and building a community that will become a prototype for the future. Thus, Disney directed the purchase of 43 square miles of virgin land--twice the size of Manhattan Island--in the center of the state of Florida. Here, he master planned a whole new "Disney world" of entertainment to include a new amusement theme park, motel-hotel resort vacation center, and his Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. After more than seven years of master planning and preparation, including 52 months of actual construction, the Walt Disney World Resort, including the Magic Kingdom Park, opened to the public as scheduled on October 1, 1971. EPCOT Center opened October 1, 1982, and on May 1, 1989, the Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park opened. A few years prior to his death on December 15, 1966, Walt Disney took a deep interest in the establishment of California Institute of the Arts, a college-level professional school of all the creative and performing arts. CalArts, Walt once said, "It's the principal thing I hope to leave when I move on to greener pastures. If I can help provide a place to develop the talent of the future, I think I will have accomplished something." The California Institute of the Arts was founded in 1961 with the combination of two schools, the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music and the Chouinard Art Institute. The campus is located in the city of Valencia, 32 miles northeast of downtown Los Angeles. Walt Disney conceived the new school as a place where all the performing and creative arts would be taught under one roof in a "community of the arts" as a completely new approach to professional arts training. Walt Disney is a legend; a folk hero of the 20th century. His worldwide popularity was based upon the ideals which his name represents: imagination, optimism, creation, and self-made success in the American tradition. Walt Disney did more to touch the hearts, minds, and emotions of millions of Americans than any other person in the past century. Through his work he brought joy, happiness, and a universal means of communication to the people of every nation. He brought us closer to the future, while telling us of the past, it is certain, that there will never be such as great a man, as Walt Disney. Photos on this page © Disney http://www.justdisney.com/walt_disney/biography/long_bio.html Walt Disney Walt Disney. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Born: December 5, 1901 Chicago, Illinois Died: December 15, 1966 Los Angeles, California American animator, filmmaker, and businessman An American filmmaker and businessman, Walt Disney created a new kind of popular culture with feature-length animated cartoons and live-action "family" films. Early life Walter Elias Disney was born in Chicago, Illinois, on December 5, 1901, the fourth of five children born to Elias and Flora Call Disney. His father, a strict and religious man who often physically abused his children, was working as a building contractor when Walter was born. Soon afterward, his father took over a farm in Marceline, Missouri, where he moved the family. Walter was very happy on the farm and developed his love of animals while living there. After the farm failed, the family moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where Walter helped his father deliver newspapers. He also worked selling candy and newspapers on the train that traveled between Kansas City and Chicago, Illinois. He began drawing and took some art lessons during this time. Disney dropped out of high school at seventeen to serve in World War I (1914–18; a war between German-led Central powers and the Allies—England, the United States, and other nations). After a short stretch as an ambulance driver, he returned to Kansas City in 1919 to work as a commercial illustrator and later made crude animated cartoons (a series of drawings with slight changes in each that resemble movement when filmed in order). By 1922 he had set up his own shop as a partner with Ub Iwerks, whose drawing ability and technical skill were major factors in Disney's eventual success. Off to Hollywood Initial failure with Ub Iwerks sent Disney to Hollywood, California, in 1923. In partnership with his older brother, Roy, he began producing Oswald the Rabbit cartoons for Universal Studios. After a contract dispute led to the end of this work, Disney and his brother decided to come up with their own character. Their first success came in Steamboat Willie, which was the first allsound cartoon. It also featured Disney as the voice of a character first called "Mortimer Mouse." Disney's wife, Lillian (whom he had married in 1925) suggested that Mickey sounded better, and Disney agreed. Disney reinvested all of his profits toward improving his pictures. He insisted on technical perfection, and his gifts as a story editor quickly pushed his firm ahead. The invention of such cartoon characters as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Minnie, and Goofy, combined with the clever use of music, sound, and folk material (as in The Three Little Pigs ), made the Disney shorts of the 1930s successful all over the world. This success led to the establishment of the hugely profitable, Disney-controlled sidelines in advertising, publishing, and merchandising. Branching out Disney rapidly expanded his studio operations to include a training school where a whole new generation of artists developed and made possible the production of the first feature-length cartoon, Snow White (1937). Other costly animated features followed, including Pinocchio, Bambi, and the famous musical experiment Fantasia. With Seal Island (1948), wildlife films became an additional source of income. In 1950 Treasure Island led to what became the studio's major product, live-action films, which basically cornered the traditional "family" market. Disney's biggest hit, Mary Poppins, was one of his many films that used occasional animation to project wholesome, exciting stories containing sentiment and music. In 1954 Disney successfully invaded television, and by the time of his death the Disney studio had produced 21 full-length animated films, 493 short subjects, 47 live-action films, 7 True-Life Adventure features, 330 hours of Mickey Mouse Club television programs, 78 half-hour Zorro television adventures, and 280 other television shows. Construction of theme parks On July 18, 1957, Disney opened Disneyland in Anaheim, California, the most successful amusement park in history, with 6.7 million people visiting it by 1966. The idea for the park came to him after taking his children to other amusement parks and watching them have fun on amusement rides. He decided to build a park where the entire family could have fun together. In 1971 Disney World in Orlando, Florida, opened. Since then, Disney theme parks have opened in Tokyo, Japan, and Paris, France. Disney also dreamed of developing a city of the future, a dream that came true in 1982 with the opening of Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT). EPCOT, which cost an initial $900 million, was planned as a real-life community of the future with the very latest in technology (the use of science to achieve a practical purpose). The two principle areas of EPCOT are Future World and World Showcase, both of which were designed for adults rather than children. Disney's business empire Furthermore, Disney created and funded a new university, the California Institute of the Arts, known as Cal Arts. He thought of this as the peak of education for the arts, where people in many different forms could work together, dream and develop, and create the mixture of arts needed for the future. Disney once commented: "It's the principal thing I hope to leave when I move on to greener pastures. If I can help provide a place to develop the talent of the future, I think I will have accomplished something." Disney's parks continue to grow with the creation of the Disney-MGM Studios, Animal Kingdom, and an extensive sports complex in Orlando. The Disney Corporation has also branched out into other types of films with the creation of Touchstone Films, into music with Hollywood Records, and even into vacations with its Disney Cruise Lines. In all, the Disney name now covers a multibillion dollar enterprise, with business ventures all over the world. In 1939 Disney received an honorary (received without meeting the usual requirements) Academy Award, and in 1954 he received four more Academy Awards. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973) presented Disney with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and in the same year Disney was awarded the Freedom Foundation Award. Walt Disney, happily married for forty-one years, was moving ahead with his plans for huge, new outdoor recreational areas when he died on December 15, 1966, in Los Angeles, California. At the time of his death, his enterprises had brought him respect, admiration, and a business empire worth over $100 million a year, but Disney was still mainly remembered as the man who had created Mickey Mouse almost forty years before. For More Information Barrett, Katherine, and Richard Greene. Inside the Dream: The Personal Story of Walt Disney. New York: Disney Editions, 2001. Green, Amy Boothe. Remembering Walt. New York: Hyperion, 1999. Logue, Mary. Imagination: The Story of Walt Disney. Chanhassen, MN: Child's World, 1999. Thomas, Bob. Walt Disney: An American Original. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976. Watts, Steven. The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. From: http://www.notablebiographies.com/De-Du/Disney-Walt.html#ixzz2IksFlJX5 Was Walt Disney Racist? Question asked and answered on: http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20110625195938AAFKb31 Original Question: I've heard rumors that he's anti-Semitic, and have had it told to me more than once he favored Hitler during WWII, but I've also heard he made anti-Nazi films during the time? Many have also said he was racist against African Americans? I know times where different back then, and most Americans were racist in some way, since the Civil Rights movement has not occurred until later in his life (40's, I believe?) and you can't teach an old dog new tricks. Please, if you answer, leave whatever website, or book you learned your answer from. I'd love to hear encounters, or stories of any evidence he was racist. Thanks in advance. by cod466 Well if you look at the three crows in older disney cartoons (you can look on youtube) it is very racist but you have to see for yourself ? I dont know how old this is, but I'm pretty sure in the states before world war 2 there was alot of big companies like disney and ford, etc. That were into the same ideas as Hitler, you can actually find videos about the sterilization ofwhat these people would believe to be sub races (below them) These people believe they're from pure families and that th have not diluted their bloodlines. Some of these people are still around as some of the wealthiest people around. America put a huge hold on this Racist activity once the world eyes saw Hitler and to the person saying is it racist to show cultures as they are, so every bad guys supposed to be black? Did white people not make them slaves? how about I'm white and if that's so every bad guy should have been white in early disney they were all depicted as darker skinned and etc. Also dont think he was pro nazi, after Hitler they couldn't sterilize people in USA anymore had to drop all that and pretend it didn't happen. by Jon he was very much nazi -favourable. if you notice that in several of his films the main villains are ment to resemble types of people he diagreed with in several ways like when they have big noses and are greedy which is meant to resemble and he viewed the jewish people like when the queen in snow white disguises herself. by Bella Moon lol Yes, Walt Disney was a racist white nationalist, he was also a pedophile. If you look at his original art and movies in the scenery you'll see. by Gabed You are correct, he was racist because he lived in a racist time. He was only about as racist as everyone else. by EspritDe... He was anti semetic according to some people but we'll never really know until we unfreeze him will we? by Need Serious Help If you approach this in a logical manner, is it really racist to depict different cultures with mannerisms and expressions that are true to the culture? Historically, do people of Siamese culture eat with chopsticks? Yes, so is showing Siamese cats in the Aristrocats as Siamese with chopsticks, singing about being Siamese, a racist statement about the Siamese people? The movie, Song of the South, is an adaptation of African stories handed down by slaves. Yes, he does speak in an old southern dialect and sounds to some as "slavish", but that was the time the stories were told, so it stays true to the culture. I believe the Disney movies are pretty true to the time periods they represent, hence, the characters depicted are true to the culture in time. Is is racist to show the truth about people? We all SHARE many mannerisms and characteristics. We can see ourselves in other people and cultures. I'm sure I can think of other races that eat with chopsticks, even the white man in America. I can think of many white people who talk in an very southern voice that call themselves redneck. Most of Disney's movies have a lesson to be learned that is for ALL cultures. Source(s): Logical thinking An Insight on Walt Disney’s Alleged Racism By “The Cartoon” 8-11-2011 It has become a popular myth that the famed Walt Disney, and the company that he created, were racist and/or anti-Semitic. It is this reason that I attempt to fairly set the record straight, and explain the slant truths and misconceptions. The biggest problem with the myth is the fact that many people spread it without understanding any of the actual facts. If you search through Yahoo Answers, you will see all sorts of people expressing this belief. They often hear it from a friend, or from a television show. Those who form their own opinions, just think about certain scenes from Disney movies as "racist," but don't know the true motive behind them. Many people fail to recognize the difference between "racism" and a "stereotype." They also must understand the significance of the time period of which these movies were created. I plan to shed light on each of these topics. To begin, I'll discuss the origin and continuation of the belief that Walt Disney himself was an antiSemite. It is difficult to say exactly when the rumor started, or why. Some believe that it was during a 1941 workers strike at Disney. But however it started, it is still to this day stated by fact as many people, and therefore spread. It certainly doesn't help when television shows spread the rumor. I specifically mention the popular show "Family Guy," which criticizes Walt for allegedly hating Jews, despite the fact that the show makes several Jewish stereotypes itself. People argue that that's alright, because "Family Guy is supposed to be like that. It criticizes everyone." That would be fair if it weren't for the hypocrisy behind it. It's easy to assume things, but if you watch Disney movies or short films, it will be a very difficult task to find even the slightest Jewish stereotype. In fact, Walt Disney created several anti-Nazi propaganda short films during the World War II era. Many say that he supported the Nazis, and was a traitor to the Americans. Those who claim that clearly haven't seen the shorts themselves, as these shorts are extremely critical of Hitler and the Nazis. Despite all of this, this generation mostly believes that Walt Disney was anti-Semitic without any proof at all. Documentation has been searched for to find proof, and none has ever been found. (1) Several Jewish workers have even come forward to defend Walt. (2) There is no evidence to support Walt Disney being anti-Semitic, but there is plenty to support that he was not. It has also been said that Walt Disney was racist against African Americans, among other ethnicities. What's odd about this accusation is that it actually makes more sense than the anti-Semitism rumor, yet it isn't nearly as wide-spread. There is in fact, evidence to support it. This being said, the belief tends to be greatly exaggerated. I'll begin by explaining the reasoning behind this one. There is no evidence of Walt Disney ever being cruel or discriminatory to anyone. And the Walt Disney Company had workers from all sorts of backgrounds. But the racism rumors were a result of stereotypes being depicted in Disney films. People do try to deny these stereotypes, but there is no denying that they were there. Such stereotypes were depicted in classic Disney short films and such feature-length films as "Fantasia," "The Three Caballeros," "Peter Pan," and several others. Many of the examples have since been edited from the films. But the stereotypes were evident and there's no use in pretending like they weren't there. With that said, there is a big difference between a "stereotype" and downright "racism." Racism is defined on Dictionary.com as "a belief or doctrine that inherent differences among the various human races determine cultural or individual achievement, usually involving the idea that one's own race is superior and has the right to rule others." (3) While the Disney Company did depict racial stereotypes, they never implied that one race was better than the other, or showed any hate toward a race. There was nothing malicious about any of the depictions. That does not excuse them. But creating these characters is no worse than telling a racist joke, which nearly all of us do. These racial stereotypes are in the back of everyone's mind, and they were even more apparent in the 1940's, where people weren't nearly as tolerant as they are now. In addition to this, Walt Disney wasn't solely responsible for every film that was worked on. It took the effort of many other workers to create his vision. He isn't to be blamed for every stereotype. This belief is backed up by the fact that there were plenty of examples of stereotypes in Disney films created after Walt's death in films such as "The Jungle Book," "Lady and the Tramp," and more. Disney was even concerned about being accused of racism, so he created Uncle Remus as the lead character of "Song of the South." Most people think that this movie is racist, and it has been banned. But Walt didn't intend it this way. He even cleared the script with Remus's actor and several organizations to try and make sure that no one would take offense. The public reaction shocked him, and hurt his reputation. (4) Point being, there are many misconceptions about Walt Disney, and the exaggerated truths are surrounded by hypocrisy. If you're going to blindly believe something without checking up on the facts, keep it to yourself and don't spread a rumor that may or may not be true. Don't even take my word for it. Look up your own facts. But from my research, Walt Disney was a tolerant person. I have yet to find any examples that demonstrate any sort of hate toward anyone. And weather you believe that or not, he was a creative genius who did amazing things for animation and the movie industry. Rather than insult him for minor flaws, let's appreciate his accomplishments. Sources: 1) http://www.cartoonbrew.com/disney/why-walt...ing-racist.html 2) http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/8...ist.html?cat=37 3) http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/racism 4) http://dailycartoonist.com/index.php/2009/...disney-a-racist Suspended Animation The URL for this page is http://www.snopes.com/disney/info/wd-ice.htm Walt Disney's health had been deteriorating for many months before he finally agreed to enter St. Joseph hospital in California on November 2, 1966, for tests concerning the pain in his leg and neck. Doctors discovered a walnut-sized spot on the x-ray of his left lung and advised immediate surgery. Disney left the hospital to attend to studio business for a few days, then re-entered St. Joseph on Sunday, November 6, for surgery the next day. During Monday morning's operation, doctors found his left lung to be cancerous and removed it. His oversized lymph nodes were an indication that Disney hadn't much longer to live. After two weeks of post-operative care, Disney was released from the hospital. He crossed the street to his studios and spent another ten days tending to studio business and visiting relatives before he grew too weak and had to return to St. Joseph on November 30. His health started to fail even more rapidly than expected, and drugs and cobalt treatments sapped what little strength he had left. Walt Disney died two weeks later when his circulatory system collapsed on the morning of December 15, 1966. In the decades since Walt Disney's death, the claim that he arranged for his body to be frozen has become ubiquitous. Nearly everyone familiar with the name 'Walt Disney' has heard the story that Disney's corpse is stored in a deep-freeze chamber somewhere -- directly under Disneyland's "Pirates of the Caribbean" attraction is the most frequently mentioned site -- awaiting the day when science can repair the damage to his body and bring 'Uncle Walt' back to life. Was Walt Disney aware of the possibilities of life extension through cryogenics? He certainly could have been aware of the progress being made in cryogenics research. Numerous articles and books on hypothermia and the preservation of animal tissue through freezing appeared in both the scientific/medical and general press in the late 1950's and early 1960's. Anyone with an interest in the subject could easily have located this reading material, and even someone without a particular interest in the subject may have run across one or more articles on the topic in the general press. The subject of cryonics was further brought to the public's attention with the publication in 1964 of Robert C.W. Ettinger's book, The Prospect of Immortality. Ettinger's book, drawing on much of the available literature about cryonics, covered the practical, legal, ethical, and moral impact of freezing and reviving human beings. Ettinger, while admitting that science had as yet no way of reviving frozen human beings, was unflaggingly optimistic that a viable means of reanimation would eventually be found, telling his readers: The fact: At very low temperatures it is possible, right now, to preserve dead people with essentially no deterioration, indefinitely. The assumption: If civilization endures, medical science should eventually be able to repair almost any damage to the human body, including freezing damage and senile debility or other cause of death. Hence we need only arrange to have our bodies, after we die, stored in suitable freezers against the time when science may be able to help us. No matter what kills us, whether old age or disease, and even if freezing techniques are still crude when we die, sooner or later our friends of the future should be equal to the task of reviving and curing us. Given the prevalence of articles published about cryonics in the mid 1960's, and the relative popularity of Ettinger's book among science buffs (even if few of them had actually read it), it is certainly possible that Walt Disney was aware of the potentiality of cryonic storage of humans. Whatever the possibilities, however, there is no documentary evidence to suggest that Walt Disney was interested in, or had even heard of, cryonics. Documentation of Disney's alleged fascination with preserving or extending his life through cryonics did not appear until decades after his death, and what little information is available has predominantly been provided by some extremely questionable sources. Claims about Disney's interest come primarily from two of the more recent Disney biographies: Robert Mosley's 1986 effort,Disney's World, and Marc Eliot's 1993 entry, Walt Disney -Hollywood's Dark Prince. Both books have been largely discredited for containing numerous factual errors and undocumented assertions, rendering them rather untrustworthy as sources of reliable background material. Eliot's biography, which dwells unrelentingly on every salacious incident and rumor connected with Walt Disney's name, is fairly easy to dismiss. Charitably described as "speculative," it contains a single passage concerning Walt Disney's alleged interest in cryonics: Disney's growing preoccupation with his own mortality also led him to explore the science of cryogenics, the freezing of an aging or ill person until such time as the human body can be revived and restored to health. Disney often mused to Roy about the notion of perhaps having himself frozen, an idea which received . . . indulgent nods from his brother . . . Not surprisingly, the source behind this piece of information is nowhere to be found in Eliot's notes. And as there is no record of Roy ever having spoken of his brother's alleged interest in cryonics, Eliot's "source" was likely nothing more than repetition of rumor. Mosley's Disney's World is also rather long on rumor and short on facts. The book has been described as "poorly researched and filled with inaccuracies", a biography that seemed "to promote certain preset points of view, regardless of evidence". The same critique goes on to say, "One of its central themes, for example, is Disney's fascination with cryogenesis and the strong suggestion that his body was frozen following his death. It makes for titillating reading; however, few facts support Mosley's claims". Disney's World paints a picture of an anxious Walt Disney desperately searching for a way to spring back to life in order to prevent or correct the horrible mistakes his followers were bound to make in turning his EPCOT dream into reality: [T]he chief problem that troubled Walt was the length of time it might take the doctors to perfect the process. How long would it be before the surgical experts could bring a treated cadaver back to working life? To be brutally practical, could it be guaranteed, in fact, that he could be brought back in time to rectify the mistakes his successors would almost certainly start making at EPCOT the moment he was dead? Mosley's book is filled with repetitions of the claim that Walt Disney grew increasingly interested in cryonics as his health waned in late 1966, such as this paragraph: It was about this time that Walt Disney became acquainted with the experiments into the process known as cryogenesis, or what one newspaper termed "the freeze-drying of the human cadaver after death, for eventual resuscitation." Mosley's statements regarding Disney's belief in the feasibility of cryonics are somewhat difficult to take seriously, given that his book includes such ludicrously erroneous (or fabricated) statements as: The surgeons had taken away his diseased lung to examine it, and then were going to preserve it. Walt was pleased when he heard that. He knew enough about cryogenesis by now to be aware that it was important to hold onto all the organs -- just in case the surgeons needed to treat them before putting them back where they belonged. (Samples of tissue removed during cancer surgery are preserved in formaldehyde, a method of "preservation" which, while useful for microscopy studies, damages the tissue biologically. Organs removed from Disney by his surgeons could never be "put back where they belonged", no matter what the treatment.) Mosley provides no source for his statements, other than to assert that Disney's "closest colleagues and advisers" were "confident" that Walt Disney "eventually became convinced of cryogenesis as a viable medical process and was persuaded that, even in 1966, it was possible for a human being to have himself brought back to life after death". In fact, these "close colleagues" of Disney's turned out to be a few employees on the periphery of the Disney organization who had never spoken to Walt about cryonics, and were merely repeating the same decades-old rumor for Mosley's benefit. On the other hand, someone much closer to Walt Disney, his daughter, Diane wrote in 1972: There is absolutely no truth to the rumor that my father, Walt Disney, wished to be frozen. I doubt that my father had ever heard of cryonics. Despite the persistent rumors, available documentation indicates that Walt Disney was in fact cremated. Although Disney's preferences regarding the disposal of his body are not public record (instructions or provisions for his funeral and burial were not included in his will), other publiclyavailable material is entirely consistent with the claim that he was cremated: Walt Disney publicly stated -- ten years before his death -- that he wished not to have a funeral. Disney family members have confirmed that cremation was Walt's wish. Disney's death certificate shows that he was cremated two days after his death. (The name, license number, and signature of the enbalmer appearing on the death certificate are those of a real enbalmer who was employed at the Forest Lawn mortuary at the time.) A marked burial plot, for Walt Disney (and his son-in-law) can be found at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale (the logical resting grounds for someone whose cremation was handled by Forest Lawn's mortuary), and court papers indicate that the Disney estate paid $40,000 to Forest Lawn for interment property. Since Disney's demise, several unmremarkable events and circumstances surrounding his life and death have been combined to try to establish a pattern of mystery and secrecy concerning the disposal of his body. All of these events, however, have straightforward, non-mysterious explanations: "Disney had a long preoccupation with death" "Disney had a neurotic fear of death" Statements concerning Disney's alleged preoccupation with death are generally attempts to sensationalize the topic by distorting the facts. Although he did worry about dying prematurely, Disney was not "obsessed with death". Having been told by a fortune-teller that he would die when he was thirty-five, Disney did brood about his inevitable demise during occasional bouts of depression, even after he had long passed the allegedly fatal age. Contemplating one's mortality is not an unusual behavior, and there is no evidence that Walt Disney did so to an excessive degree. William Poundstone quotes some ridiculous passages from Anthony Haden-Guest's The Paradise Program to try to establish Disney's preoccupation with death, detailing a "gruesome seven-minute Mickey Mouse cartoon" made in 1933 in which "a mad scientist tries to cut off Pluto's head and put in on a chicken. The cartoon in question is The Mad Doctor, which was nothing more than humorous spoof of 1930's horror films. Even in the cartoon itself the "horrific" events are not portrayed as real: the whole episode turns out to be nothing more than a nightmare of Mickey's. Although Poundstone wrote that the film was pulled from the Rank film library in 1970, it has been readily available in the Mickey Mouse: The Black and White Years laserdisc set since 1994. "The news of Disney's death was deliberately delayed." This claim that the announcement of Walt Disney's death was deliberately withheld from the press for several hours has been made most persistently, presumably because Disney's aides would have needed time to furtively whisk his body away from the hospital to the secret cryogenic chamber before the presence of reporters made the task impossible to accomplish in privacy. Leonard Mosley's description of the event features some of more absurd stretches of truth made in this regard: And this is where the mystery begins. It was Walt himself who had asked Roy Disney to keep his illness secret, but the manner in which the world was apprised of his death remains surprising. In fact, it was not until hours after he was declared dead that an announcement was made. First came radio announcements, then a curt official notice informed the press and public that Walt Disney was no more. It added that there would be no funeral. He had already been cremated, the announcement said, and his ashes interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. Only immediate family members had been present. It is true that Disney's death was not officially announced to the press until several hours after it occurred at 9:30 AM on Thursday, December 15, 1966, but the reasons behind the delay were perfectly ordinary ones. First of all, Disney's death would not have been announced immediately under any circumstances. Several family members had to be notified before a public announcement could be made, and Disney studio executives had to be located and informed that the head of their organization had passed away before the information would be released to the press. Additionally, the gravity of Disney's illness had largely been kept a secret from the press, so there were no hordes of reporters crowding the hallways of St. Joseph Hospital, waiting for the inevitable announcement of his death. The reason for Disney's original hospitalization had been announced to the press as "treatment of an old neck injury received while playing polo," and when Disney re-entered the hospital for the final time two weeks before his death, the statement made to the press was that Disney was undergoing "a routine post-operative" checkup. Although it was certainly no secret that Disney was quite ill, the seriousness of his condition was not generally known. The extent to which the details of Walt Disney's illness were kept from the press are evidenced by the newspapers reports of his death, which stated that his left lung had been removed during an operation on November 21 (an error which Poundstone repeats in Big Secrets). That operation had actually taken place two weeks earlier; November 21 was the date of his original post-surgery release from the hospital. So, given that relatives and studio heads had to be notified before any statements about Disney's death were made to the press; that the media were not on a "Disney death watch," busily preparing obituaries and tributes; and that communications in 1966 were certainly slower than they are today, it is not at all surprising that official news of Disney's death did not reach the public until a few hours later. Mosley's other statements, about Disney's funeral and cremation, are just further examples of sloppy research on his part. Disney was not cremated until two days after his death; no press announcement made "hours after he was declared dead" claimed that he had already been cremated. "The cause of Disney's demise was never formally announced." < This>statement is both inaccurate and irrelevant. The cause of Disney's death was initially announced as being "acute circulatory collapse," which meant simply that his heart had stopped beating. As facile as the official announcement may seem to those who know he "really" died of lung cancer, it does reflect the proximate cause of his death. This notion is borne out by the official death certificate, which lists "cardiac arrest" as the primary cause of death. The fact that cancer was what caused Disney's heart to give out was, medically, of secondary importance. Official statements released to the press after Disney's surgery (and before his death) had already revealed that a tumor had been found, necessitating the removal of a lung. Whether stated "officially" or not, it was quite clear to the public that Disney had died of lung cancer. In any case, what possible difference could it have made what Walt Disney died of? How could dissembling about the "real" cause of his death possibly have facilitated the goal of secretly storing his body in a cryonic chamber? "Disney's funeral services were held in secret." Disney's funeral was in fact conducted quickly and quietly -- at the Little Church of the Flowers in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Glendale -- at 5:00 PM on Friday, December 16 (the day after his death). No announcement of the funeral was made until after it had taken place, no associates or executives from Disney Studios were invited, and only immediate family members were in attendance. Forest Lawn officials refused to disclose any details of the funeral or disposition of the body, stating only that "Mr. Disney's wishes were very specific and had been spelled out in great detail.". None of this secrecy surrounding Disney's funeral should be the least bit surprising to anyone, however. In the biography The Story of Walt Disney, written a decade before Disney's death, his daughter Diane had noted: He never goes to a funeral if he can help it. If he had to go to one it plunges him into a reverie which lasts for hours after he's home. At such times he says, 'When I'm dead I don't want a funeral. I want people to remember me alive.'" Is it so remarkable that a man who had an aversion to funerals -- and who had stated a ten years earlier that he didn't want a public funeral -- was sent off with a very quick and very private ceremony? If the clandestineness of the funeral had been intended to cover up the fact that Disney's body had already been deposited in liquid nitrogen at a secret facility, there were certainly better, less obvious ways of accomplishing the deception: Disney could have been given a simple closed-casket ceremony, with nobody the wiser. "Disney specified the public was never to be told the location of his grave." Again, this claim is not the least bit extraordinary. It is true that officials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park will not divulge the location of the Disney family plot. Many celebrities do request that the locations of their burial plots not be given out to visitors as a simple matter of privacy. The burial sites are not intended to be "secret," however; if they were, they wouldn't be marked and located on publicly-accessible grounds. Disney's plot was not, as Mosley claimed, "already filled with family ashes from which the public would always be barred." Disney's plot is far from obtrusive, but it is located in an unrestricted part of the park and marked with a plaque identifying its occupants; anyone who so desires is perfectly free to visit, leave flowers, take photographs, etc. The plot was certainly not "already filled with family ashes" at the time of Disney's interment; even today it holds the remains of only one other person: Ron Brown, a son-in-law who died the year after Disney. In fact, according to the book Wills of the Rich and Famous, the interment property was not even chosen until September 19, 1967, making it rather difficult to believe that it could have been "already filled with family ashes." If Disney was not really frozen, then how and when did this rumor originate? The exact origins of the rumor are unknown, but at least one Disney publicist has suggested that the story was started by a group of Disney Studio animators who "had a bizarre sense of humor." The earliest known printed version of the rumor appeared in the magazine Ici Paris in 1969. Even if the origins of the story are unknown, it is certainly easy to see why the rumor is so believable. In the years immediately preceding his death, Disney was involved in a number of projects which cemented his image as a technical innovator in the public's mind. Disneyland attractions such as the monorail, the House of the Future, the Voyage to the Moon; the introduction of audio-animatronic figures at the 1964 World's Fair, and Disney's plans for his "community of tomorrow" (EPCOT) in Florida made it easy to believe Walt Disney was ahead of everyone else in his planning, even when it came to his death. When you consider that the first cryonic suspension took place just a month after Disney's death (Dr. James Bedford, a 73-year-old psychologist from Glendale, was suspended on January 12, 1967), it's not so far-fetched to imagine that Disney might have made similar arrangements. Was Walt Disney Racist? By Caleb C Jul 24, 2011 0 Walt Disney is arguably one of the most influential figures (if not THE most influential figure) in children's entertainment in the 20th century. With such iconic characters as Mickey Mouse, and such classic films as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” Disney has left behind the kind of legacy that filmmakers and cartoonists everywhere dream about. But was there a dark side to Walt Disney? Some believe that Disney was racist, and perhaps even a Nazi sympathizers, but do these charges have any merit? Some of Disney's cartoons did have some pretty racial imagery. Take, for instance, the black crows in “Dumbo,” one of which is actually named Jim Crow. The crows use such jargon as “I be done seen 'bout everything when I see an elephant fly.” Racially stereotypical depictions are also seen in films like “Fantasia” (the centaurs), “Lady and the Tramp” (the Siamese cats), “The Jungle Book” (King Louie the monkey) and of course “Song of the South” (Uncle Remus). Some people might also point to racially stereotypical depictions in films like “The Lion King” and “Aladdin,” but as these were made after Walt Disney's death, I won't include them. Some of Disney's short cartoons also featured racially stereotypical illustrations. One well-known example includes “The Three Little Pigs,” in which the Big Bad Wolf is briefly shown as a Jewish peddler. Disney did not animate the sequence himself, but he did approve it. So with examples such as these, can we safely assume that Disney was racist? It may provide little consolation to some if I were to propose that exaggerated racial stereotypes were commonplace in the early to mid 20th century, and were not necessary perceived as malicious. For instance, minstrel shows (in which performers appeared in blackface and took on exaggerated African American personas) were once popular with black and white audiences alike, and short films like the “Our Gang” (later known as “The Little Rascals”) series featured many racial stereotypes, but were in later years vehemently defended by the black cast mates. I do not mean to suggest that racial stereotyping and minstrel shows amount to good, innocent entertainment. I deplore such things. But I do hope to put the issue into perspective by illustrating Disney's work given the context of its time period. Disney may not have seen racial aspects of his work as being “racist” because the entertainment world was a very different place. James Baskett, who played Uncle Remus in “Song of the South” (one of Disney's most notoriously racial pieces of work) was given an honorary Academy Award “for his able and heart-warming characterization” (of the title character). Disney himself campaigned personally for Baskett in the Academy Award race, and Baskett went on to become the first male African American ever to receive an Oscar. Ultimately, you must look at Disney's body of work and make up your own mind as to whether or not the iconic filmmaker was racist. You can certainly make a strong argument that his work was often racially insensitive, but you could also argue strongly that some of his work glorified the occult or promoted freemasonry. Art, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Read more at http://www.infobarrel.com/Was_Walt_Disney_Racist#mrJirXpiq3DSIO8r.99 Walt Disney -- Prince or Toad? ESSAY The studio pioneer's detractors insist that he was racist and mean. A deeper look shows that the truth about the man is far more complicated. November 22, 2009|By Neal Gabler Even before it opens later this week, Disney's new animated feature, "The Princess and the Frog," is already considered something of a cultural and animation landmark. After centering cartoons on a Middle Easterner ("Aladdin"), a Native American (" Pocahontas"), an Asian ("Mulan"), and a Hawaiian ("Lilo & Stitch"), Disney animation has entered the post-racial era. The new film features a black protagonist alongside the green one. It has been a long time coming, but it is an event that, if you believe Disney detractors, would have old Walt spinning in his grave (or his cryogenic chamber). That's because there is a long-standing belief among those detractors that Walt Disney was anything but the amiable, avuncular, kind-hearted figure he appeared to be on his television program and in his promotions. The real Disney, so this version goes, was a rabid reactionary who was intemperate, crabbed and mean -- racially and ethnically insensitive at best, a racist and anti-Semite at worst. Under his supervision, the Disney studio was inhospitable to minorities, few of whom were said to have worked there and they were virtually verboten on the screen, except to be ridiculed. Disney's was a white, Protestant, middle-class studio and fantasy. Minorities need not apply. How much of this portrait was the product of a smear campaign by Walt's enemies and how much a product of Walt's own unenlightened attitudes is difficult to determine. What one can say is that the truth about Walt Disney seems much more complicated and nuanced than either his enemies or supporters would have you believe. Labor fight Disney came by those enemies honestly when his animators staged a strike in 1941 complaining of paternalism and low wages and Walt responded by hustling the supposed union ringleaders off the lot and firing other union members to quash their organizing. Even after the four-month-long strike was settled -- under duress by the federal government -- the wounds did not heal. Disney would feel betrayed for the rest of his life by what he saw as ungrateful employees. The aggrieved employees got their own measure of revenge by portraying Walt thereafter in the least flattering light. Most of what we hear about Disney as a racist or anti-Semite was circulated by animators who had struck in 1941. I know, because several of them made the same charges to me when I was working on my biography of Disney. Unquestionably, especially after the strike, Disney was a political conservative by way of anticommunism. He was certain that the strike was instigated by communist agents in the Screen Cartoonists Guild who were determined to sully the Disney brand -- this after Disney had been extolled by the left for years for his collaborative enterprise and exemplary working conditions. Though Walt was something of a political naïf -- he had no interest in politics before the strike and little after it -- he was an easy recruit for the most reactionary elements in Hollywood. They enlisted him to join an organization called the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals that was really dedicated less to preserving American ideals than to ridding the film industry of leftists. This was Walt's war too. Still, the organization was so toxic to much of Hollywood -- many of its members were known anti-Semites -- that even such staunch anti-communists as Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner declined to join. And yet even if Walt were guilty by association -- and he was -- it would be unfair to label him an anti-Semite himself. There is no evidence whatsoever in the extensive Disney Archives of any antiSemitic remarks or actions by Walt -- only a few casual slurs by his brother Roy. Moreover, Joe Grant, the one-time head of the Disney Model Department and an esteemed story man, was Jewish, as was Harry Tytle, a longtime production executive, and the head of the Disney merchandise arm was a Jewish entrepreneur named Herman "Kay" Kamen, with whom Walt was especially close. Though the studio, as one of the only ones in Hollywood not operated by Jews, had the reputation of being less than minor- ity friendly, prompting Tytle to confess to Walt that he was half-Jewish. Tytle told me that Walt responded by quip- ping that he'd be better if he were all Jewish.