Deliverable 3.1: Needs mapping and Action Learning

advertisement

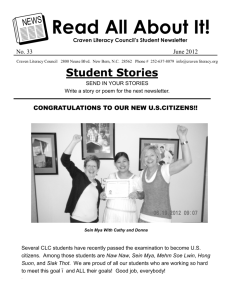

Improving School Governance using an Action Learning Approach 527856-LLP-1-2012-1-PT-COMENIUS-CMP Work Package 3: Methodology, Needs Analysis and Common Governance Model Deliverable 3.1: Needs mapping and Action Learning Set methodology Document information Due date of deliverable 30/04/13 Actual submission date 30/07/13 Organisation name of lead contractor for this Ellinogermaniki Agogi deliverable Version 1 Dissemination Level P PP Public □ x Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the □ Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the □ Commission Services) This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 1 DELIVERABLE REVIEW HISTORY Version Name Status * Date Summary of changes Final5 Valentina Diagene (University of Vilnius) PR 2013/12/05 Add summary or indicate clearly where it is; check text for misspelling; Final 5 Rodrigo Queiroz e Melo (UCP) SIR 2013/12/05 Final Eleni Chelioti (EA) Author 2013/12/06 The current final version has been revised based on the reviewers’ comments *Status: Indicate if: Author (including author of revised deliverable) - A; PIR – Primary internal reviewer; SIR – Second internal reviewer; ER – External Reviewer Quality Control Check Y/N Reviewer recommendations/comments Generic Minimum Quality Standards Document Summary provided (with adequate synopsis of contents) Y IGUANA format standards complied with Y Language, grammar and spelling acceptable Y Objectives of Description of Work covered Y Work deliverable relates to adequately covered Y Quality of text is acceptable (organisation and structure; diagrams; readability) Y Comprehensiveness is acceptable (no missing sections; missing references; unexplained arguments) Y Usability is acceptable (deliverable provides clear information in a form that is useful to the reader) Y Deliverable specific quality criteria Deliverable meets the 'acceptance Criteria' set out in the Quality Register (see Table 5) Y For Supplementary Review Deliverables only Deliverable approved by external reviewers Checklist completed by 2 Name: Rodrigo Queiroz e Melo (UCP) Signature: Date: 2013/12/05 Y/N Reviewer recommendations/comments Document Summary provided (with adequate synopsis of contents) N There is introductory part “About this document” but in my opinion it is not summary. IGUANA format standards complied with Y Language, grammar and spelling acceptable Y Objectives of Description of Work covered Y Work deliverable relates to adequately covered Y Quality of text is acceptable (organisation and structure; diagrams; readability) Y Text is structured very clear, easy to read and understand Comprehensiveness is acceptable (no missing sections; missing references; unexplained arguments) Y (summary is missing) Usability is acceptable (deliverable provides clear information in a form that is useful to the reader) Y Quality Control Check Generic Minimum Quality Standards Deliverable specific quality criteria Deliverable meets the 'acceptance Criteria' set out in the Quality Register (see Table 5) Y It would be better to make more precisely citation (where is Table 5) For Supplementary Review Deliverables only Deliverable approved by external reviewers Checklist completed by Name: Valentina Dagiene 3 Signature: Date: 2013/12/05 Work Package 3: Methodology, Needs analysis and common governance model Deliverable 3.1: Needs mapping and Action Learning Set methodology Author: Eleni Chelioti (Ellinogermaniki Agogi), Joe Cullen (ARCOLA Research) July, 2013 4 CONTENTS Table of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 6 1. About this Document ............................................................................... 7 2. Overall approach ..................................................................................... 9 3. Documentation analysis............................................................................................................ 11 4. Modelling .................................................................................................................................. 15 5. User Survey ............................................................................................................................... 22 6. Action Learning Sets.................................................................................................................. 24 References ................................................................................................... 26 APPENDIX .................................................................................................... 28 IGUANA Project School survey ..................................................................... 29 SECTION 1: About you and your school ............................................................................................ 29 SECTION 2: Emotional intelligence in the school .............................................................................. 30 SECTION 3: Developing Organizational innovation........................................................................... 34 5 Table of Figures Figure 1 Relationship between the three WP3 deliverables .................................................................. 7 Figure 2 Triangulation of needs assessment......................................................................................... 11 Figure 3 IGUANA Learning Model ......................................................................................................... 15 Figure 4 The cycle of negative reinforcement ...................................................................................... 16 Figure 5 The Theory of Change ............................................................................................................. 19 6 1. About this Document D3.1 “Needs mapping and Action Learning Set methodology” is the first of the three deliverables that comprise IGUANA WP3. The objectives of WP3 “Methodology, Needs analysis and common governance model” are to assess and validate the training needs of key stakeholders in different school governance types in order to support the mission of IGUANA to develop a training programme that will help schools break out of a cycle of stuckness. This document presents the methodology for the training needs assessment and validation, and the particular methods, processes and tools that IGUANA used for this purpose. This deliverable will form the basis for the common training model, guidelines and standards that will be presented in D3.2, while the results of the needs assessment and validation process will be reported in D3.3. D3.1 •Needs mapping and Action Learning Set methodology. •This sets out the methodology used to identify the learning and training needs of the IGUANA target users D3.2 •Common training model, guidelines and standards •This applies the needs assessment methodology to identify user needs and to develop the overall common training model for IGUANA target users on the basis of these needs D3.3 •Training Needs Report. •This presents the results of the validation of the common training model, and provides an assessment of the extent to which the model addresses the identified needs of IGUANA users Figure 1 Relationship between the three WP3 deliverables As Figure 1 shows, D3.2 “Common training model, guidelines and standards” will show how the methodology presented in D3.1 was used to elicit initial needs from IGUANA target users, and then how the results of this needs elicitation process, that will be reported in D3.3, were then used to develop a preliminary common training model for IGUANA. 7 In order to describe the methodology for the needs assessment, this document starts with a section on the Documentation Analysis, describing the types of literature that were reviewed as well as the review process, as well as the particular input from the report of WP2 on Governance Systems across Europe, and input from other official documents and reports. Then the “Modelling” approach is described, namely the process for developing an initial prototype model of the IGUANA platform that would be tested and validated, as well as the elements that comprise the IGUANA learning framework. The two final sections of this report present the tools for needs collection, assessment and validation of the learning framework, i.e. the purpose and process of developing the IGUANA survey and the action learning set within the overall needs assessment approach. 8 2. Overall approach The objectives of IGUANA are to develop a training framework that will help schools innovate and overcome ‘stuckness’ and resistance to change. ‘Stuckness’ is addressed as a key-factor that inhibits school development in a series of parameters. The overall IGUANA approach is based on the definition that schools’ stuckness is a situation where schools are enmeshed in problematic circumstances in persistent and repetitive ways, despite desire and effort to alter the situation. Although this problem is associated with teachers’ stresses and anxieties, ‘stuckness’ is not merely an individual but a school problem. The Iguana project will set out to achieve these goals by developing a collaborative learning platform (WP4) which will provide teachers, managers and governors tools for assessing their current capacity to innovate as well as respective content and toolkits (WP5) for developing these skills. Within this framework the work of WP3 is to assess and validate the training needs of these stakeholders. While the initial work-plan identified a more open-ended and generic approach to training needs, the methodology of WP3 was adapted to the particular focus that the IGUANA learning approach took on emotional intelligence. This focus, that was presented in WP5, is based on the assumption that school organisational innovation, and breaking out of ‘stuckness’, requires the application of techniques of emotional intelligence to the school. Therefore the needs assessment focuses particularly on stakeholders’ training needs in terms of the components and competences that are associated with emotional intelligence and innovation capacity of the school. This means taking into account three broad types of need : subscibed (or ‘felt’ needs) – the needs that IGUANA users themselves perceive they would like addressed ; ascribed needs – the needs that other key stakeholders in the field (particularly policy-makers and researchers) perceive are necessary to deliver effective school governance ; prescibed needs – the essential user needs that have to be satisfied by IGUANA according to the evidence available. A substantial body of theory and research suggests that these kinds of needs are determined by underlying ‘values’ associated with people’s particular ‘reference group’ – the social and cultural ‘envelope’ in which people communicate and interact. This envelope is shaped by a number of dynamics – the most important of which are social stratification systems and processes ; 9 environment and ‘habitat’ and work and organisational structures and processes. Underpinning this is the idea of ‘expectancy-value theory’ – the notion that identification with a particular reference group and its values will determine the kinds of needs that are subscribed, ascribed and prescribed within that group. In turn, these needs will engender a set of expectations within the group that will be satisfied if these needs are met (Newcomb, 1961 ; Caspi and Herbener, 1990). Expectancy-value theory argues that decision-making – in this case whether to participate in IGUANA and its learning programme – involves an assessment of three things : the extent to which IGUANA satisfies needs ; the expectations of the rewards likely to be realised by participating, and the expectancy of the ‘success’ of these needs being met and the rewards obtained. In this context, the needs assessment approach has to work with complex dynamics, including: capturing the ‘context’ of need – the social, cultural and organisational factors that shape the different types of need in the diffferent ‘life worlds’ of the target groups reflecting the ways in which needs are socially constructed by these different groups mapping and understanding how power relations shape needs and how variations in power have to be managed to enable a ‘consensus’ of need to be determined Established needs assessment approaches recognise these complexities and most emphasise the importance of incorporating ‘triangulation’ in assessment methodologies. Triangulation allows for the synthesis of evidence of different types and from different sources, using diferent ways of capturing and assessing needs, in order to arrive at a balanced ‘consensus’ of need. In particular, a key aim of triangulation is to capture and reflect the ‘voice’ of different stakeholders in order to identify and understand their different positions and perspectives. Triangulation supports generalisability and transferability of findings in needs assessment because it increases the ‘robustness’ and transferability of findings through cross-checking of data derived from different sources and from different actors thus helping to boost the internal validity of the needs assessment. 1 A number of approaches (Kaufman et al, 1993; Barbazette, 2006) 2 3 suggest using a multi-methodological approach, combining a range of data collection and analysis methods, to enable the different dimensions of needs (subscribed, ascribed and prescribed) to be identified in this way. The suggested approach entails four broad stages: i) 1 O'Donoghue and Punch K, 2003). O'Donoghue, T., Punch K. (2003). Qualitative Educational Research in Action: Doing and Reflecting. Routledge 2 Kaufman, R Rojas, A and Mayer H (1993). Needs Assessment: A User's Guide. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications 3 Barbazette, (2006) Training Needs Assessment: methods, tools and techniques. Pfeiffer 10 establishing the purposes, objectives and approach for the assessment ii) data collection ii) gaps analysis iv) developing an action plan to address the gaps. Within this overall framework, a range of data collection methods are typically used. These depend on the type of stakeholders involved; the context in which the stakeholders participate and the uses to which the needs assessment data collected are put. The methods applied typically include: documentation review, expert panels and Delphi Panels, focus groups, surveys, interviews, task analysis, observation. The IGUANA needs assessment methodology built on this broad approach, using a ‘triangulation model’ illustrated below in Figure 2. Figure 2 Triangulation of needs assessment As Figure 1 shows, the needs assessment methodology combines: multiple sources of data; multiple ways of evaluating these data and the representation of the different stakeholder ‘voices’ that will be participating in IGUANA. Four data collection methods are incorporated in the methodology: documentation analysis modelling user survey action learning sets These are discussed further below. 3. Documentation analysis The first stage in the needs assessment is a review of the available literature on school governance systems. This drew on the material obtained through IGUANA work package 2 Comparative Review of school governance structures and approaches – with a particular focus on identifying the needs of target users. The material analysed covered four main areas: 11 Literature on the national context - practices and organisations (universities, institutions providing teacher training, teachers’ unions) dealing with school governance, education policies and teacher and governor training Literature on the policy environment - key features of the national policy documents and strategies concerning education policies on school governance; existing school leader, teacher and school governors competencies frameworks; underlying dynamics that cause stuckness within the school organisation Level, nature and type of training currently available to school governors, managers and teachers State of the art in emotional intelligence theory and practice, including the features of existing assessment tools The documentation analysis adopted a ‘realist review’ method to analyse the material (Weiss, 1995; Pawson et al, 2005) 4 5. Essentially, realist review looks at how something is supposed to work, with the goal of finding out what strategies work for which people, in what circumstances, and how. The review starts with identification and clarification of the research purposes, focusing on the key questions the research needs to address, in this case: what does the literature tell us about the needs of IGUANA target users? Since the review uses ‘secondary’ data, the focus of the review is on identifying and interpreting the ‘subscribed needs’ of target users. Subsequent stages of the review entail an iterative process of: mapping the key ‘drivers’ that shape policy and practice; searching the field for ‘evidence’, including ‘grey’ literature to identify a long list of items of concepts, policies and training practices; analysing the material collected to produce a comprehensive review of state of the art; integrating the results to produce conclusions and recommendations on ‘what works, for whom under what circumstances’ in terms of user needs. Analysis of the material selected is carried out using content analysis (Stemler, 2001) 6 . The content analysis procedure is based on a manual scanning of collected documents using a coding frame that analyses the item to identify: 4 Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. (2005), Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005 Jul;10 Suppl 1:21-34. 5 Weiss, C 1995. "Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families." In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts, ed. James P. Connell et al. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. 6 Stemler, S (2001) An introduction to content analysis 12 the needs that can be identified the main descriptors that define these needs how these needs are currently addressed through training provision the key gaps that can be identified in relation to ‘un-met needs’ More particularly the input from the Report on School Governance in the EU (WP2) that helped to develop the work, content as well as the survey that WP3 produced concerned mainly the following: - The identified need for “specialized” training for school governance. - The fact that teachers seem to view innovative teaching and learning activities as ways to overcome barriers posed by central policies or weaknesses. - The fact that, based on the review, emotional intelligence is seen as lacking intellectual rigor, while “stuckness” as a concept does not appear in the literature on schools and change, and the review found no programmes aimed at supporting schools in working with stuckness. Also, emotional intelligence is seen as ambiguous and ambivalent concept by both the research and scientific community and the teaching profession. On the one hand, it is viewed as an important life skill, but on the other as lacking intellectual rigor - The diverse and complex nature of the school systems across countries and diverse systems of governance within each country. The WP2 review also identified that there is diverse and complex professional representation (e.g.there are different types of school governors across countries, or no governors at all in other countries). This particularly provided input for determining school heads’/ governors’ statuses in the survey that was developed in WP3 - The conclusion that with the exception of the United Kingdom, there is no reference to emotional intelligence in school education. Even in the UK emotional intelligence is not directly embedded in teaching practice, i.e. it is not specifically referenced as part of the National Curriculum. Only specific skills that are targeted in teaching programmes, such as the “Citizenship” programme, coincide with the emotional intelligence domain. - The conclusion that emotional intelligence is also not directly provided in teacher training although it is significant that the 2010 Education White Paper includes new assessments of "aptitude, personality and resilience" for candidates seeking to enter teaching. In addition, the White Paper stresses the need for teachers to concentrate on ‘managing behaviour’. - Overall, as the report concludes, there is little research and evidence on the role school governors play in changing the organisational culture of schools. 13 This input from the report of WP2, was then enriched with information from other documents and reports that provided information, which helped identify two types of school governance upon which the analysis of the IGUANA survey data will be performed, i.e. countries with central governing systems / countries with non-central school governing systems. More specifically, these sources include other documents and reports from OECD (2011, 2012) regarding school autonomy across countries, EURYDICE (2007). The UNICEF country profiles (http://www.unicef.org/ceecis/) were also consulted in order to collect evidence for countries that were not included in the IGUANA WP2 countries’ reports but needed to be also categorized, since there were survey respondents from these countries (i.e. Μοntenegro, Slovenia, Denmark, Ukraine). Based on this evidence, plus the input of the WP2 report, the countries were grouped in two types: a) Countries with central school governing systems: Greece, France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium (French speaking), Montenegro and Ukraine. b) Countries with non-central school governing systems, displaying a greater extent of school autonomy: UK, the Netherlands, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Belgium (Flemmish speaking), Slovenia and Denmark. 14 4. Modelling The next stage in the needs assessment methodology entailed developing an initial prototype model of the IGUANA platform, tools and content structure. This was developed on the basis of the results of the documentation analysis. The model is shown schematically in Figure 3. Assessment Tool Learning Programme Activities • Emotional Intelligence (Individual) • Innovation Capacity (Organisational) • Emotional Intelligence/Literacy development • Organisational and Leadership development • Evaluation capacity development • Action Learning Sets • Assignments • Benchmarking • Peer Review Figure 3 IGUANA Learning Model As Figure 2 shows, the proposed IGUANA learning model combines three inter-connected elements within a dynamic learning process. The first element of this model is the self-assessment tools. These are intended to: introduce users to the IGUANA ‘landscape’ – stuckness and getting unstuck – by presenting them with various representations of emotional intelligence, stuckness, innovation capacity and evaluation capacity provide a way for users to situate themselves, and their schools, in this landscape – by taking them through an exploration of the topography of the landscape to see where they are located 15 on the basis of this exploration, identify the learning needs of users and their institutions provide some recommendations on how IGUANA could best serve these learning needs. The assessment tools therefore provide the bridge to the second element of the IGUANA learning environment – the learning programme itself. This is comprised of three ‘spaces’: the emotional intelligence/literacy space the organisational development and leadership space the evaluation space The main purpose and objectives of these learning spaces are to address the learning needs identified by the self-assessment tools. Therefore, an essential requirement of the structure and content of all three elements of the IGUANA learning programme is that they match the structure and content of the self-assessment tools. The details of the structure and content of these spaces are set out in Deliverable 3.2, but broadly, they cover the following: Emotional intelligence/literacy space The emotional intelligence component of the learning programme aims to support IGUANA users to explore the dynamics that create anxieties and defensive positions. It focuses in particular in getting participants to identify key behavioural and socio-cultural drivers that govern how their self-image and self-esteem is shaped, how they are linked to performance anxieties and feelings of not being good enough, and how, in turn, they reinforce cycles of guilt, helplessness and stuckness. It addresses the problem that school members are pressurised to perform to benchmarks that, for many of them are unattainable. For governors and heads, these are most clearly linked to academic performance targets set by government and other agencies. If I get it right everything will be OK So I must try harder to get it right Because I'm not good enough Figure 4 The cycle of negative reinforcement 16 Everything is not OK It must be my fault Teachers have to cope with similar pressures of meeting targets imposed by government standards bodies; aligning professional practice with changes in the curriculum; balancing work and life; meeting the duty of care they have to students whilst dealing with their sometimes challenging behaviour. For students, academic pressures are compounded by the emotional load of conformance to peer pressure, coping with bullying, being and staying popular and navigating their way through the minefields of the ‘risk society’. In schools, the fetishisation of performance and the pressure to achieve impossible perfectibility typically imposes a recurrent vicious circle of negative reinforcement, illustrated in Figure 4. The emotional intelligence learning space aims to help to break this cycle by providing learning content to strengthen resilience; reduce anxiety; promote ‘good-enough-ness’ and support confidence and self-esteem building for school members by replacing unattainable learning goals with realistic goals that evolve as the emotional intelligence capacity evolves. Organisational development and leadership space This learning space aims to provide a way of exploring how schools get stuck and how to break out of a repetitive cycle of stuckness. Although schools, like most organisations, appear to function logically and rationally, developing and applying explicit tasks; systems of organisation; rules and mechanisms to resolve conflict, there is plenty of evidence that, under the surface, schools, like all organisations, also operate in irrational ways. This ‘underground’ behaviour is often driven by ‘unconscious’ processes and typically surfaces as dysfunctionality and resistance to change. The ‘systems psychodynamic’ approach to understanding organisations has long argued that organisations typically act as ‘defences against anxiety’ by operating in ‘groupish’ mode (Bion, 1961; Miller,1996). 7 8 ‘Groupishness’ works in unconscious mode in three main ways to enable members of organisations to implement strategies to deal with issues around leadership and authority. The members of the educational enterprise may deploy defensive strategies against anxiety, with members adopting a dependency position by putting their faith in an omnipotent leader (the ‘superhead-teacher’) to solve their not-good-enoughness. They may adopt a ‘fight-flight’ position by demonstrating aggression or withdrawal, or a ‘splitting’ position, pairing off into splinter groups, based on divisions like departmental allegiance, in the hope of producing an alternative leader who can rectify their not-good-enoughness (Bion, 1961). They can take a ‘one-ness’ position, in which group members come together as one, for the purpose of joining in a powerful union with an 7 Bion, W (1961)Experiences in Groups. Tavistock, London Miller, E. (1993) From Dependency to Autonomy: Studies in Organization and Change. London: Free Association Books 8 17 omnipotent force (Turquet, 1974), 9 or a ‘me-ness’ position, in which the group behaves as if it is there to be saved from its irrational feelings by being a non-group (Lawrence et al 1996). 10 As a result of these fears around change, staff in schools may also exhibit ‘mirroring’ behaviours that sabotage organisational innovations, by replicating the perceived obstructive behaviours of their students (Cardona, 1999). 11 The organisational development and leadership learning space also draws on the ‘governmentality’ literature (Cotoi, 2011). 12 This looks at how, in the neo-liberal era, agencies of government delegate techniques of control and discipline to intermediaries (like the school) and to individuals themselves. Put simply, the objective of governmentality is to create the conditions through which organisations and individuals become ‘auto-regulating’, so that they become important mechanisms for processes of ‘normalisation’. Normalisation is defined as a specific technique for setting social norms adherence to which is rewarded and deviation from which is punished. It is also a more generalised technique through which disciplinary discourses become taken for granted and seen as ‘normal’. Normalisation is intimately linked to self-assessment and self-regulation, since the individual who seeks to achieve normality will do so by constantly measuring their behaviour and performance against accepted yardsticks, and by working to control their conduct, under the guidance of others, to ensure that these norms are inculcated into others with whom the individual interacts. Schools are powerful instruments for the administration of techniques of normalisation. On the one hand, this fulfils a socially beneficial function, since they help to inculcate attitudes, behaviours and practices that in turn contribute to social capital and social cohesion. However, the downside to normalisation is that it discourages, and punishes ‘marginal practices’ – thinking, behaviour and actions that are innovative, ‘out of the box’, challenging, or scary. To address these learning challenges, the organisational and leadership learning space in IGUANA aims to create a ‘positive holding environment’ in which these anxieties, defensive positions and cycles of negative reinforcement can be surfaced, explored and worked with (Winnicott, 1965) . 13 The learning resources supporting the holding environment incorporate: working with groupishness; exploring the emotional life of the organisation; the school as an ‘open system’; creating safe 9 Turquet, P M (1974) Leadership, the individual and the group, in Gibbard, G S , JJ Hardman and R D Mann eds. Analysis of Groups, San Fransisco, Josey-Bass 10 Lawrence, W. G, Bain, A. and Gould, L.J. (1996). The fifth basic assumption. Free Associations, Vol. 6, Part One, Number 37. 11 Cardona, F (1999) The team as a sponge: how the nature of the task affects the behaviour and mental life of the team. in Vince V. & French R(Eds.) in Group relations, management and Organization, Oxford University Press 12 Cotoi, C (2011) Neoliberalism: a Foucauldian Perspective, International Review of Social Research, 1: 2, 109-124 13 Winnicott, D (1965) Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development , International Universities Press 18 spaces to explore change; the school as a performance; politics, compliance and normalisation; the school as a learning organisation; using evaluation for change. Evaluation space The evaluation component of the learning programme is seen as critical to positive learning reinforcement. Embedding evaluation dimension into the learning programme will generate iterative feedback loops to support ‘double loop learning’ for individuals, participating schools and IGUANA as a whole (Argyris & Schön, 1996). 14 Individual and group self-evaluation enables members of the IGUANA learning community to assess their progress in coming unstuck. This is done through ‘theory of change’ (Pawson and Tilley, 1997; Weiss, 1995). 15 16 Theory of change identifies both the explicit and implicit paradigms of change that underlie interventions. An initial task for the members of the learning group will therefore be to identify and map the presenting problem (stuckness) and the theory of action that they think will support them in coming unstuck. This then feeds into a plan to promote organisational change. The plan provides a logical framework for organisational change that will specify; the actions required to operationalize this theory (inputs); the expected outputs of the actions; the expected outcomes associated with the use of these outputs; the longer term impacts; how the outcomes and impacts will be measured (Figure 5) Context Input Output The presenting problem stuckness What is invested skills, people, activities What has been produced Context indicator s Resourc e / input indicator Outcomes Impact Short and medium term Long- term outcomes results Output indicat ors Outcom e / result indicator Impact indicator s ‘Distance travelled’ indicators Figure 5 The Theory of Change 14 Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1996) Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice, Reading, Mass: Addison Wesley 15 Pawson R and N Tilley (1997) Realistic Evaluation, Sage, London 16 Weiss, C 1995. "Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families." In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts, ed. James P. Connell et al. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. 19 The theory of change ‘journey’ can be plotted at a range of points along the school’s ‘change journey’ - from ‘context’, through ‘inputs’ through to ‘outputs’, then ‘outcomes’ and finally ‘impacts’. Theory of change can be used as a device to assess how far the educational enterprise has progressed in relation to its ultimate goal of ‘coming unstuck’, i.e. the ‘distance travelled’. It can also be used at the individual level to enable a member of the participating learning group to assess their progress in relation to their individual goals, set against their personal ‘zone of proximal development’ (see section 3 below). In this context, distance travelled can be linked to the measurement of ‘soft outcomes’ that are integral to the emotional intelligence component of the learning programme, for example the measurement of sense of well-being and of self-esteem. The evaluation element of the learning programme will therefore provide resources on: evaluation design; developing a theory of change; putting the theory of change into practice; assessing the distance travelled in the ‘change journey’. The third element of the IGUANA learning framework is the ‘Activities’ element. The purpose and objectives of this element is to apply the learning content acquired in the learning programme, and the initial competences acquired by working with the content, to specific tasks. This is intended to operationalize the learning through ‘learning by doing’ so that the initial competences acquired through participating in the programme are enhanced, and they become useful for IGUANA users because they are applied in everyday practices. Four sets of activities are proposed: Action Learning Sets Assignments Benchmarking Peer Review Action Learning Sets These are interactive workshops which have three purposes: to involve the user group in an exercise that applies what they have learned from the programme to a specific issue affecting their school; to use the results of the exercise to critically review the IGUANA learning programme; on the basis of the review, to make recommendations to improve the programme. The workshops will use an approach based on ‘Action Learning Sets’ (Pedler, 1997). 17 T his approach provides an ‘open and safe’ space to enable critical reflection to take place; represents the different ‘voices’ and points of view of key stakeholders in the domain and promotes ‘sensemaking’ and the development of a 17 Pedler, M. (1997) Action Learning in Practice, 3rd edn. Aldershot, Gower 20 common understanding of the IGUANA learning programme and what, if any, changes need to be made to it. Assignments Assignments are tasks set by IGUANA for members of the IGUANA learning community. They entail putting into practice the learning acquired through participating in the learning programme. A specific assignment will be set for each of the three learning programme elements. Benchmarking The purpose of the benchmarking element is to support the participating schools in achieving their desired change outcomes by providing them with a way of assessing how they are doing on this journey, by comparing their practices to ‘general’ good practices (identified from the literature) but also the practices of the other schools participating in IGUANA. The overall benchmarking approach proposed is taken from the BENVIC project.18 The methodology is based on ‘strategic benchmarking’ and involves observing how other schools work. 19 The benchmarking exercise will capture good practice in a format which will enable sharing of the knowledge generated with stakeholders Peer Review This supplements the benchmarking by supporting the participating schools in sharing their experiences of the ‘change journey’. The purposes of peer reviews are to help schools further define their change programme, the target population, emphasising the links to possible outcomes and impacts and how to measure these; use the support and challenge of ‘critical friends’ as a way to further developing success criteria and improve implementation and outcomes; develop evidencebased data on emerging outcomes and impacts; provide participating schools with the opportunity to test ideas and implement changes to their programme as these progress.; create an evaluation culture. 18 19 Cullen, J (2002) The BENVIC Benchmarking Indicators Manual, BENVIC Consortium, Brussels The Benchmarking Book, Stapenhurst, T (2009) Elsevier 21 5. User Survey The next stage of the needs assessment approach entails designing and implementing a survey of target users (Appendix). The main purposes of this survey are: To validate the IGUANA learning model described above To collect additional data on user needs The focus of this part of the needs assessment approach is on identifying and understanding the ‘subscribed needs’ of IGUANA users – i.e. their ‘felt needs’ - in order to triangulate and compare these needs with the ‘prescribed needs’ identified through the documentation analysis. The IGUANA learning framework validation survey was designed in two phases: it initially adopted a generic approach to school heads’/governors’ needs, that was then adapted to the focus of the project on emotional intelligence and innovation capacity of the school. This second version was piloted by 25 respondents (school heads and school governors) from Lithuania, Greece, Ireland, Belgium, Portugal and the Netherlands, who provided feedback for amendments that would make the phrasing of the questions more meaningful for respondents from different school governance contexts. In order to validate the learning approach of IGUANA and the assessment tool developed by WP5, the key areas that the survey focused on were: - How do school governors and head teachers currently work in the three areas the IGUANA programme works in, i.e.: emotional intelligence; organisational and leadership development; evaluation capacity development? - What training has been so far provided in these three areas? - What training do they think they need in these three areas? - To what extent are the emotional intelligence competence areas specified by the IGUANA pedagogical framework used in their schools and who do they involve? - Do they have any training and experience in using these competences? - Do they need training and experience in using these competences? - How would they apply these competences in their professional practice? - What is the current situation in their school with regard to the seven innovation capacity components specified by WP5 ? 22 The survey was structured in three sections: SECTION 1: Basic information on the respondents and their schools: - Gender - Country - Status (Head of School, School governor/, Head teacher/ Teacher) - Level of school (Primary, Secondary, Other) - Type of School (General, Special Needs, Vocational, Other) - State or Private school - School location (Urban/ Private/ Other) SECTION 2: Emotional intelligence in the school This section included 4 sets of questions focusing on: 1) How emotional intelligence is currently applied in the school with particular reference to 5 parameters: school governance, management of school, recruitment of staff, development of curriculum and teaching practice 2) Whether training is provided currently in the following forms: a. As part of training for governors b. As part of training and professional development of staff c. For students, as a dedicated subject d. For students, but not as a dedicated subject e. As part of training for parents f. As part of training for senior management 3) Whether there is need for training in emotional intelligence for each one of these groups: School governors, senior management, teaching staff, non-teaching staff, students, parents. 4) The amount of staff in the school that demonstrates each one of the 12 emotional intelligence competences (based on input from WP5) SECTION 3: Developing Organizational Innovation The purpose of this section is to investigate the extent to which the school already has the structures and processes that can support organizational innovation and openness to change. It includes two sets of items focusing on: 23 - Evaluating the school on 19 competences/ practices that are associated with the innovation capacity of the school - Assessing whether there is need for training in the school in each one of the components that are associated with innovation capacity (based on WP5): o effective leadership and authority, o working together as group, o applying emotional well-being to support organisational change, o working with external organisations, o balancing discipline and rules with risk-taking and creativity, o using evaluation to support organisational change, o creating spaces for reflection and critical review. In order to familiarize the respondents with the concepts of emotional intelligence and innovation capacity, each one of the sections included an introductory paragraph explaining these concepts as well as the objective and focus of the section. In terms of multiple choice questions and use of Likert scales, a 4-point scale with an additional “Don’t know” option was used, in order to avoid neutral responses. The questionnaire is available to be filled in online https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1pCnjaL2SSfSCp68-u-oc4FRFh9oQrASMfjWSXYdAvm0/viewform and the results of the analysis will be reported in D3.3. 6. Action Learning Sets The final part of the needs assessment methodology involves running an Action Learning Set with a key group of potential IGUANA users. As with the User Survey, the purposes of the Action Learning Set are: To validate the IGUANA learning model described above To collect additional data on user needs The Action Learning Set can be seen as an additional refinement in the cycle of needs assessment. It focuses on ‘prescribed needs’, i.e. addressing the gaps in needs provision that can be identified as a result of successive iterations of needs assessment data collection and analysis. 24 As noted above, Action Learning Sets are a particular type of Focus Group which provides an ‘open and safe’ space to enable critical reflection to take place; represents the different ‘voices’ and points of view of key stakeholders in the domain and promotes ‘sensemaking’ and the development of a common understanding of the IGUANA learning model and what, if any, changes need to be made to it. The approach entails a form of ‘role-playing’ in which the workshop participants split into three groups, each of which takes on the role and perspective of a key stakeholder, i.e.: governors; teachers; students. This approach has been selected because: it encourages interaction, knowledge sharing and co-learning between participants it enables ‘hidden’ factors and dynamics – such as values and belief systems – that underlie needs to be surfaced and explored it enables the different ‘voices’ of different stakeholder groups to be heard it supports ‘sensemaking’ and promotes ’needs consensus’. The action learning set methodology is particularly suited to addressing three key, and inter-related, sets of issues that militate against developing and implementing relevant learning and training programmes. Firstly ,it recognises the important role played by normative factors, such as beliefs and values, in shaping needs. As Brouselle (2009) observes: “We should recognize that program theory does not reflect the way in which the intervention produces the intended outcomes, but rather reflects stakeholders’ perceptions and beliefs, right or wrong, about the mechanisms that operate between the delivery of the intervention and the intended outcomes.” 20 Secondly, it highlights the ways in which needs are contextualised. This leads to diversity in interpretation of needs. Thirdly, therefore, it is essential to provide a space within the workshop environment that enables the different contexts of need, and different stakeholder perspectives, to be explored in order to promote ‘sensemaking’ and needs consensus. The workshop has a ‘primary task’, which is: to validate the IGUANA model. As noted above, Action Learning Sets work by creating a space in which participants can share knowledge and experience; take on different ‘roles’ that reflect the voices and perspectives of different stakeholders; identify and reflect on how these different voices and perspectives reflect values and beliefs that shape needs, and, ultimately, through ‘sense-making’, arrive at a consensus on appropriate strategies and actions. 20 Brouselle, A (2009) ‘How about a logic analysis? A quick evaluation capitalising on best knowledge’, European Evaluation Society Conference, Praha, 2009 25 References 26 Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1996) Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice, Reading, Mass: Addison Wesley Barbazette, J. (2006) Training Needs Assessment: methods, tools and techniques. Pfeiffer Bion, W (1961)Experiences in Groups. Tavistock, London Cardona, F (1999) The team as a sponge: how the nature of the task affects the behaviour and mental life of the team. in Vince V. & French R(Eds.) in Group relations, management and Organization, Oxford University Press Cotoi, C (2011) Neoliberalism: a Foucauldian Perspective, International Review of Social Research, 1: 2, 109-124 Cullen, J (2002) The BENVIC Benchmarking Indicators Manual, BENVIC Consortium, Brussels EURYDICE (2007) School Autonomy in Europe: Policies and Measures http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/090EN.pdf Kaufman, R Rojas, A and Mayer H (1993). Needs Assessment: A User's Guide. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications Lawrence, W. G, Bain, A. and Gould, L.J. (1996). The fifth basic assumption. Free Associations, Vol. 6, Part One, Number 37. Miller, E. (1993) From Dependency to Autonomy: Studies in Organization and Change. London: Free Association Books O'Donoghue and Punch K, 2003). O'Donoghue, T., Punch K. (2003). Qualitative Educational Research in Action: Doing and Reflecting. Routledge OECD (2012) Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes, Country Background Report for the Netherlandshttp://www.oecd.org/edu/school/NLD_CBR_Evaluation_and_Assessment.pdf Pawson R and N Tilley (1997) Realistic Evaluation, Sage, London Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. (2005), Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005 Jul;10 Suppl 1:21-34. Pedler, M. (1997) Action Learning in Practice, 3rd edn. Aldershot, Gower PISA in Focus (2011) School autonomy and accountability: Are they related to student performance? http://www.oecd.org/pisa/48910490.pdf Stemler, S (2001) An introduction to content analysis http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED458218.pdf Turquet, P M (1974) Leadership, the individual and the group, in Gibbard, G S , JJ Hardman and R D Mann eds. Analysis of Groups, San Fransisco, Josey-Bass Weiss, C 1995. "Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families." In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts, ed. James P. Connell et al. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. Weiss, C 1995. "Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families." In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts, ed. James P. Connell et al. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. 27 Winnicott, D (1965) Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development , International Universities Press APPENDIX 28 IGUANA Project School survey ABOUT THIS QUESTIONNAIRE IGUANA is a two-year research project co-funded by the European Commission under the ‘Lifelong Learning Programme’. It works with schools that want to innovate but encounter resistance to change. The project will help schools to establish an open and creative environment in which students, staff and management feel safe and secure to share their ideas, learn from each other and grow. IGUANA is particularly interested in two aspects of school innovation: • how ‘emotional intelligence’ can contribute to school development • how schools work as ‘learning organisations’ To help us make IGUANA more relevant and effective, we are asking school heads and senior staff to complete a short questionnaire on how these two aspects are currently considered in their schools, and how they might be further developed in the future. When completing the questionnaire, we would ask you to answer the questions below from the perspective of your school as a whole, on the basis of your knowledge and experience. All responses will be anonymised and your answers will remain confidential. Thank you for your time! * Required SECTION 1: About you and your school 1.1 Gender * o o Male Female 1.2 Your country: * o Belgium o Portugal o Ireland o Greece o Netherlands o UK o Lithuania o Other: 1.3 Your status: * Please check all boxes that apply 29 o Head of school o School governor o Head teacher o o Teacher Other: 1.4 Level of your school: * If the school is both Primary and Secondary, please check both boxes. o Primary o Secondary o Other: 1.5 Type of school: * o General o Special Needs o Vocational o Other: 1.6 State/ private school: * o State o Private o Other: 1.7 School location: * o Urban o Rural o Other: SECTION 2: Emotional intelligence in the school In this section we are interested in how ‘emotional intelligence’ is thought of and applied in your school, and how it might be applied to support school innovation in the future. For the purposes of this survey, we define emotional intelligence as “the ability to understand, express and manage our own emotions, and respond to the emotions of others, in ways that are helpful to ourselves and others.” Bearing this definition in mind, please answer the following questions. 2.1 To what extent would you say emotional intelligence is applied NOW in your school in the following ways: * Please check the relevant box for each item. Not at all In governance 30 the of A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know Not at all A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know the school (i.e. in how the governing body operates) In the management of the school (i.e. how management team operates) In recruitment of staff In developing the teaching curriculum In teaching practice 2.2 Is training in emotional intelligence competences currently provided in your school in the following areas? * Please check the relevant box for each item. Yes As part of training for school governors As part of training professional development staff and For students, as a dedicated subject within the school curriculum 31 No Don't know Yes No Don't know For students, within particular subjects but NOT as a dedicated subject As part of training for parents As part of training for senior management 2.3 For which of the following groups shown below, do you think there is a need for training in emotional intelligence in your school? * Yes No Don't know School governors Senior management Teaching staff Non-teaching staff Students Parents 2.4 The table below provides a list of emotional intelligence competences. Thinking about your school as a whole – i.e. from the perspective of the organization – how many staff would you say consistently demonstrate the following competences: * None Emotional selfawareness and awareness of the individuals’ relationship with their work 32 Few Most staff All of staff Don't know None environment Self-confidence and awareness of personal qualities Accepting the limitations of a situation in relation to personal qualities and abilities Sensing other people’s emotions and imagining what they could be thinking or feeling Awareness social responsibility of Handling relationships (communicating and supporting others, managing conflicts) Coping with and adapting to challenges Recognising and taking responsibility for own actions Recognising opportunities and taking the lead 33 Few Most staff All of staff Don't know None Few Most staff All of staff Don't know for resolving situations of stuckness Recognizing and managing anxiety Recognizing and managing stress Identifying factors that are associated with optimism and happiness SECTION 3: Developing Organizational innovation In this Section we want to find out to what extent your school has the structures and processes in place to support organizational learning and innovation. For the purposes of this questionnaire, we define a ‘learning and innovation organisation’ as: “organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is supported, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together”. Bearing this definition in mind, please answer the following questions. 3.1. To what extent would you say that the following apply in your school generally? * Not at all All the members of the school are encouraged to critically review established norms and practices. Opportunities are given for making new suggestions and changing established patterns. 34 A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know Not at all When working in groups, members of the group tend to avoid taking responsibility for decisions. When working in groups, group members can express themselves without overrelying on the leader or other external agents for support. The group dynamics allow for diversity of thought and exploration of difference among its members. When working in groups, individual positions are more highly valued than the collective position of the group. Staff members are encouraged to take initiatives on their own. Staff members are conscious of their feelings and know how to deal with them. 35 A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know Not at all Staff members are afraid of making choices and taking risks. All tasks undertaken are primarily oriented towards the progress and development of the school as a whole. The school is open to collaborate with other organisations, schools, or the local community. When collaborating with other stakeholders (other schools, local community), your school is open to their suggestions and reflection. The school rules and discipline routines inhibit creativity and innovation in your school. There is pressure on the school (teachers, students, managers) to 36 A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know Not at all A little A significant To a amount extent great Don't know perform outstandingly. Evaluation is used in the school to support organizational change and innovation. Evaluation is used as a means for students’ learning. Evaluation of the staff is used as means for reflection and professional development. Sharing of knowledge, ideas and practices takes place on a regular basis Staff members have regular opportunities for critical reflection that promotes learning and development. 3.2 The following list describes a set of organizational competences that have been suggested help schools to innovate. For which of the competences listed do you think that there is need for training in your school? * Yes Effective 37 leadership No Don't know Yes and authority Working together as a group Applying emotional well-being to support organisational change Working with external organisations Balancing discipline and rules with risktaking and creativity Using evaluation to support organisational learning Creating spaces for reflection and critical review 38 No Don't know