Elia Kazan - Mr Powell's Learnatorium

advertisement

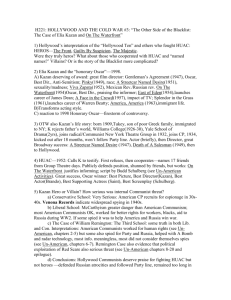

Elia Kazan Elia Kazan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Elia Kazan (IPA: [eˈlia kaˈzan]; September 7, 1909 – September 28, 2003) was an American director, producer, writer and actor, described by The New York Times as "one of the most honored and influential directors in Broadway and Hollywood history".[4] He was born in Istanbul, Ottoman Empire, to ethnic Greek parents. After studying acting at Yale, he acted professionally for eight years, later joining the Group Theater in 1932, and co-founded the Actors Studio in 1947. With Lee Strasberg, he introduced Method acting to the American stage and cinema as a new form of selfexpression and psychological "realism". Kazan acted in only a few films, including City for Conquest (1940).[5] Kazan introduced a new generation of unknown young actors to the movie audiences, including Marlon Brando and James Dean. Noted for drawing out the best dramatic performances from his actors, he directed 21 actors to Oscar nominations, resulting in nine wins. He became "one of the consummate filmmakers of the 20th century" after directing a string of successful films, including, A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), On the Waterfront (1954), and East of Eden (1955). During his career, he won two Oscars as Best Director and received an Honorary Oscar, won three Tony Awards, and four Golden Globes. Among the other actors he introduced to movie audiences were Warren Beatty, Carroll Baker, Julie Harris, Andy Griffith, Lee Remick, Rip Torn, Eli Wallach, Eva Marie Saint, Martin Balsam, Fred Gwynne, and Pat Hingle. Elia Kazan, c. 1960 Elias Kazanjoglou[1] (Greek: Ἠλίας Born Καζαντζόγλου) September 7, 1909 Istanbul, Ottoman Empire Died Occupation Years active September 28, 2003 (aged 94) New York City, New York, USA Director, actor, producer, screenwriter and novelist 1934–1976 Martin Scorsese, John Influenced Cassavetes, Francis Ford Coppola,[2] Stanley Kubrick[3] Molly Day Thacher His films were concerned with personal or social issues of special concern to him. Kazan writes, "I don't move unless I have some empathy with the basic theme."[6] His first such "issue" film was Gentleman's Agreement (1947), with Gregory Peck, which dealt with subtle anti-Semitism in America. It received 8 Oscar nominations and 3 wins, 1|Page (m. 1932–1963; her death) Spouse(s) Barbara Loden (m. 1967–1980; her death) Frances Rudge (m. 1982–2003; his death) including Kazan's first for Best Director. It was followed by Pinky, one of the first films to address racial prejudice against Blacks. In 1954, he directed On the Waterfront, a film about union corruption in New York, which some consider "one of the greatest films in the history of international cinema."[7] A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), an adaptation of the stage play which he had also directed, received 12 Oscar nominations, winning 4, and was Marlon Brando's breakthrough role. In 1955, he directed John Steinbeck's East of Eden, which introduced James Dean to movie audiences, making him an overnight star. A turning point in Kazan's career came with his testimony as a "friendly witness" before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952 at the time of the Hollywood blacklist, which brought him strong negative reactions from many liberal friends and colleagues. Kazan later explained that he took "only the more tolerable of two alternatives that were either way painful and wrong".[8] Kazan influenced the films of the 1950s and '60s with his provocative, issue-driven subjects. Director Stanley Kubrick called him, "without question, the best director we have in America, [and] capable of performing miracles with the actors he uses."[9][3]:36 Film author Ian Freer concludes that "If his achievements are tainted by political controversy, the debt Hollywood—and actors everywhere—owes him is enormous."[10] In 2010, Martin Scorsese co-directed the documentary film, A Letter to Elia, as a personal tribute to Kazan.[11][12] Kazan Kazan directing Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire Among the themes that would run through all of his work were "personal alienation and an outrage over social injustice", writes film critic William Baer.[7] Other critics have likewise noted his "strong commitment to the social and social psychological—rather than the purely political—implications of drama".[18]:33 2|Page Actors Studio With playwright Tennessee Williams in 1967. Kazan directing ‘Splendour in the Grass’. In 1947, he founded the Actors Studio, a non-profit workshop, with actors Robert Lewis and Cheryl Crawford. It soon became famous for promoting "Method," a style of theater and acting involving "total immersion of actor into character," writes film author Ian Freer.[10] According to Rapf, "the Studio rode the bandwagon of method fashionability, and Kazan was its clear star and attraction."[18]:97 Within a short time, as word spread, "everyone wanted to be at the Studio—not least because of the chance of being in a Kazan production in one medium or another."[18]:97 Among its first students were Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Julie Harris, Eli Wallach, Karl Malden, Patricia Neal, Mildred Dunnock, James Whitmore, and Maureen Stapleton. In 1951, Lee Strasberg became its director, and it remained a non-profit enterprise, eventually considered "the nation's most prestigious acting school," according to film historian James Lipton.[27] Student James Dean, in a letter home to his parents, writes that Actors Studio was "the greatest school of the theater [and] the best thing that can happen to an actor".[28] Playwright Tennessee Williams said of its actors: "They act from the inside out. They communicate emotions they really feel. They give you a sense of life." Contemporary directors like Sidney Lumet, a former student, have intentionally used actors such as Al Pacino, a former student skilled in "Method".[29] In 1954 he again used Brando as co-star in On the Waterfront. As a continuation of the socially relevant themes that he developed in New York, the film exposed corruption within New York’s longshoremen’s union. It too was nominated for 12 Academy Awards, but won 8, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor, for Marlon Brando. To some critics, Brando gives the "best performance in American film history,"[10] playing an ex-boxer, Terry Malloy, who is persuaded by a priest to inform on corrupt unions. Surprisingly, Brando writes that he was actually disappointed with his acting upon first watching the screening: 3|Page On the day Gadg showed me the completed picture, I was so depressed by my performance I got up and left the screening room. I thought I was a huge failure. I was simply embarrassed for myself. ... I am indebted to him for all that I learned. He was a wonderful teacher.[31] The film made use of extensive on-location street scenes and waterfront shots, and included a notable score by composer Leonard Bernstein. British film critic Ian Freer notes that despite Kazan naming Communist party members to the House Committee on Un-American Activities two years earlier, "the film is ambivalent about the act of informing."[10] HUAC testimony See also: Hollywood Blacklist Kazan remained controversial in some pro-communist circles until his death for testimony he gave before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1952, a period that many, such as journalist Michael Mills, feel was "the most controversial period in Hollywood history."[46] When he was in his mid 20s, during the Depression years 1934 to 1936, he had been a member of the American Communist Party in New York, for a year and a half. In April 1952, the Committee called on Kazan, under oath, to identify Communists from that period 16 years earlier. Kazan initially refused to provide names, but eventually named eight former Group Theater members who he said had been Communists: Clifford Odets, J. Edward Bromberg, Lewis Leverett, Morris Carnovsky, Phoebe Brand, Tony Kraber, Ted Wellman, and Paula Miller, who later married Lee Strasberg. He testified that Odets quit the party at the same time that he did.[47] All the persons named were already known to HUAC, however.[4][48] The move cost Kazan many Jewish friends within the film industry, including playwright Arthur Miller. Kazan would later write in his autobiography of the "warrior pleasure at withstanding his 'enemies.'[49] When Kazan received an Honorary Academy Award in 1999, the audience was noticeably divided in their reaction, with some including Nick Nolte, Ed Harris, Ian McKellen and Amy Madigan refusing to applaud, and many others, such as actors Kathy Bates, Meryl Streep and Warren Beatty and producer George Stevens, Jr. standing and applauding.[50] Stevens speculates on why he, Beatty, and many others in the audience chose to stand and applaud: I never discussed it with Warren, but I believe we were both standing for same reason—out of regard for the creativity, the stamina and the many fierce battles and lonely nights that had gone into the man's twenty motion pictures.[6] Mills notes that prior to becoming a "friendly witness," Kazan discussed the issues with Miller: 4|Page To defend a secrecy I don’t think right and to defend people who have already been named or soon would be by someone else... I hate the Communists and have for many years, and don’t feel right about giving up my career to defend them. I will give up my film career if it is in the interests of defending something I believe in, but not this.[46] Miller put his arm around Kazan and retorted, "don’t worry about what I’ll think. Whatever you do is okay with me, because I know that your heart is in the right place."[46] In his memoirs, Kazan writes that his testimony meant that "the big shot had become the outsider." He also notes that it strengthened his friendship with another outsider, Tennessee Williams, with whom he collaborated on numerous plays and films. He called Williams "the most loyal and understanding friend I had through those black months."[16]:495 His controversial stand during his testimony in front of the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities (HUAC) in 1952, became the low point in his career, although he remained convinced that he made the right decision to give the names of Communist Party members. He stated in an interview in 1976: I would rather do what I did than crawl in front of a ritualistic Left and lie the way those other comrades did, and betray my own soul. I didn't betray it. I made a difficult decision.[7] In 1999, when he was 90 years old, Kazan received an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement. During the ceremony, he was accompanied by Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. The propriety of such an honor for Kazan who "named names" at the HUAC hearings remains a "contentious subject" according to the New York Times.[54] Many in Hollywood felt that enough time had passed that it was appropriate to finally recognize Kazan's great artistic accomplishments, although others did not and would not applaud.[55][56] Kazan appreciated the award: I want to thank the Academy for its courage, its generosity. Thank you all very much. Now I can just slip away.[57] In his autobiography, A Life, he sums up the influence of filmmaking on his life: I realize now that work was my drug. It held me together. It kept me high. When I wasn't working, I didn't know who I was or what I was supposed to do. This is general in the film world. You are so absorbed in making a film, you can't think of anything else. It's your identity, and when it's done you are nobody.[16]:260 Martin Scorsese has directed a film documentary, A Letter to Elia (2010), considered to be an "intensely personal and deeply moving tribute" to Kazan. Scorsese was "captivated" by Kazan's films as a young man, and the documentary mirrors his own life story while he also credits Kazan as the inspiration for his becoming a filmmaker.[11][12] 5|Page 6|Page